The Diversity of Fijian Polities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Socio-Cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women's

A Socio-cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women’s Perception of and Responses to HIV and AIDS from the Two Selected Tribes in Rural Fiji Tabalesi na Dakua,Ukuwale na Salato Ms Litiana N. Tuilaselase Kuridrani MBA; PG Dip Social Policy Admin; PG Dip HRM; Post Basic Public Health; BA Management/Sociology (double major); FRNOB A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Population Health Abstract This thesis reports the findings of the first in-depth qualitative research on the socio-cultural perceptions of and responses to HIV and AIDS from the two selected tribes in rural Fiji. The study is guided by an ethnographic framework with grounded theory approach. Data was obtained using methods of Key Informants Interviews (KII), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), participant observations and documentary analysis of scripts, brochures, curriculum, magazines, newspapers articles obtained from a broad range of Fijian sources. The study findings confirmed that the Indigenous Fijian women population are aware of and concerned about HIV and AIDS. Specifically, control over their lives and decision-making is shaped by changes of vanua (land and its people), lotu (church), and matanitu (state or government) structures. This increases their vulnerabilities. Informants identified HIV and AIDS with a loss of control over the traditional way of life, over family ties, over oneself and loss of control over risks and vulnerability factors. The understanding of HIV and AIDS is situated in the cultural context as indigenous in its origin and required a traditional approach to management and healing. -

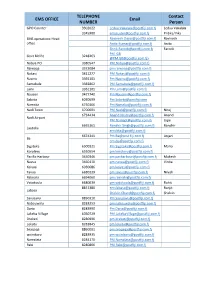

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Tuesday-27Th November 2018

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … 10 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 10-11 Point of Order … … … … … … … … … … 11-12 Debate on His Excellency the President’s Address … … … … … 12-68 List of Speakers 1. Hon. J.V. Bainimarama Pages 12-17 2. Hon. S. Adimaitoga Pages 18-20 3. Hon. R.S. Akbar Pages 20-24 4. Hon. P.K. Bala Pages 25-28 5. Hon. V.K. Bhatnagar Pages 28-32 6. Hon. M. Bulanauca Pages 33-39 7. Hon. M.D. Bulitavu Pages 39-44 8. Hon. V.R. Gavoka Pages 44-48 9. Hon. Dr. S.R. Govind Pages 50-54 10. Hon. A. Jale Pages 54-57 11. Hon. Ro T.V. Kepa Pages 57-63 12. Hon. S.S. Kirpal Pages 63-64 13. Hon. Cdr. S.T. Koroilavesau Pages 64-68 Speaker’s Ruling … … … … … … … … … 68 TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 The Parliament resumed at 9.36 a.m., pursuant to adjournment. HONOURABLE SPEAKER took the Chair and read the Prayer. PRESENT All Honourable Members were present. MINUTES HON. LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT IN PARLIAMENT.- Madam Speaker, I move: That the Minutes of the sittings of Parliament held on Monday, 26th November 2018, as previously circulated, be taken as read and be confirmed. HON. A.A. MAHARAJ.- Madam Speaker, I beg to second the motion. Question put Motion agreed to. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome I welcome all Honourable Members to the second sitting day of Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 session. -

Current and Future Climate of the Fiji Islands

Rotuma eef a R Se at re Ahau G p u ro G a w a Vanua Levu s Bligh Water Taveuni N a o Y r th er Koro n La u G ro Koro Sea up Nadi Viti Levu SUVA Ono-i-lau S ou th er n L Kadavu au Gr South Pacific Ocean oup Current and future climate of the Fiji Islands > Fiji Meteorological Service > Australian Bureau of Meteorology > Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Fiji’s current climate Across Fiji the annual average temperature is between 20-27°C. Changes Fiji’s climate is also influenced by the in the temperature from season to season are relatively small and strongly trade winds, which blow from the tied to changes in the surrounding ocean temperature. east or south-east. The trade winds bring moisture onshore causing heavy Around the coast, the average night- activity. It extends across the South showers in the mountain regions. time temperatures can be as low Pacific Ocean from the Solomon Fiji’s climate varies considerably as 18°C and the average maximum Islands to east of the Cook Islands from year to year due to the El Niño- day-time temperatures can be as with its southern edge usually lying Southern Oscillation. This is a natural high as 32°C. In the central parts near Fiji (Figure 2). climate pattern that occurs across of the main islands, average night- Rainfall across Fiji can be highly the tropical Pacific Ocean and affects time temperatures can be as low as variable. On Fiji’s two main islands, weather around the world. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Fijian Colonial Experience: a Study of the Neotraditional Order Under British Colonial Rule Prior to World War II, by Timothy J

Chapter 4 The new of The more able Fij ian chiefs did not need to fetch up the glory of their ancestors to maintain leadership of their people: they exploited a variety of opportunities open to them within the Fij ian Administration. Ultimately colonial rule itself rested on the loyalty chosen chiefs could still command from their people, and day-to-day village governance, it has been seen, totally depended on them. Far from degenerating into a decadent elite, these chiefs devised a mode of leadership that was neither traditional, for it needed appointment from the Crown, nor purely administrative. Its material rewards came from salary and fringe benefits; its larger satisfactions from the extent to which the peopl e rallied to their leadership and voluntarily participated in the great celebrations of Fijian life , the traditional-type festivals of dance, food and ceremony that proclaimed to all: the people and the chief and the land are one . 'Government-work' had its place, but for chiefs and people there were always 'higher' preoccupations growing out of the refined cultural legacy of the past (albeit the attenuated past) which gave them all that was still distinctively Fij ian in their threatened way of life. This chapter will illuminate the ambiguous mix of constraint and opportunity for chiefly leadership in the colonial context as exercised prior to World War II by some powerful personalities from different status levels in the neotraditional order. Thurston's enthusiastic tax gatherer, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi , was perhaps the most able of them , and in his happier days was generally esteemed as one of the finest of 'the old school' of chiefs . -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

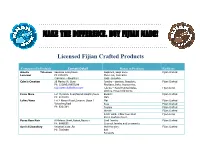

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik -

Cannibal Chiefs and the Charter for Rebellion in Rotuman Myth

PACIFIC STUDIES Vol. 10, No. 1 November 1986 CANNIBAL CHIEFS AND THE CHARTER FOR REBELLION IN ROTUMAN MYTH Alan Howard University of Hawaii A prominent theme in Rotuman myth concerns rebellion against oppressive chiefs. Encoded in the myths are strong oppositions between “chiefs” and “peo- ple of the land,” chiefs being associated with the sky, sea, east, north, and coast; people of the land with the earth, land, west, south, and inland. An analysis of available narratives suggests that chiefs are in an ambiguous position since their role requires a combination of vitality, expressed in the form of demands upon their subjects, and domestication, expressed through generosity. Excesses of the latter characteristic imply chiefly impotence, excesses of the former, oppression. The narratives suggest that supernatural supports are available for insurrections against oppressive chiefs, who are the conceptual equivalents of cannibals, and for usurpation of their authority by successful rebels. The instrumental role of women as victim provocateurs, mediators with the supernatural, and leaders of rebellion is also detailed. It is argued that the myths explore various permuta- tions of the dilemma of chieftainship and provide a charter for rebellion against chiefs whose demands are perceived as excessive. The island of Rotuma lies approximately three hundred miles north of Fiji, on the western fringe of Polynesia, Linguistic evidence suggests that Rotuman belongs in a subgrouping (Central Pacific) that includes Fijian and the Polynesian languages, and that within this group there is a special relationship between Rotuman and the languages of western Fiji (Pawley 1979). However, the vocabulary shows a considerable degree of borrowing from Polynesian languages (Biggs 1965; Pawley 1962), and Rotuman cultural patterns fall well within the range of those Pacific Studies, Vol. -

2017-12-Phd-Rokolekutu.Pdf

INTERROGATING THE VANUA AND THE INSTITUTIONAL TRUSTEESHIP ROLE OF THE ITAUKEI LAND TRUST BOARD (TLTB): UNDERSTANDING THE ECONOMIC MARGINALIZATION OF ITAUKEI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII AT MANOA IN PARTIAL FULLFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DECEMBER 2017 PONIPATE ROKOLEKUTU Dissertation Committee: Nevzat Soguk, Chairperson Manfred Henningsen Noenoe K.Silva Hokulani Aikau Tarcisius Kabutaulaka Copyright 2017 By Ponipate Rokolekutu ii Dedicated to: my late paternal grandparents: Ilaisa and Elina Kalouca late Nei: Lice Tinai Matatolu & late mother: Miriama Soronaqaqa Rokolekutu iii Acknowledgments I never thought that this part of the dissertation would be difficult. But it is difficult to acknowledge those who have made this journey bearable, meaningful and even enjoyable. My journey to the academic summit would have been insurmountable without God’s grace and the enduring love and support of my loved ones. This journey would also be impossible without the support of my committee chair, and the invaluable advice from the members of my dissertation committee who distinguish scholars in their fields. It would have been certainly unbearable without the friendships and collegiality of significant individuals whom I have had the privilege to interact with, both within the academic environment, as well as, around the kava bowl and the so many meals shared in homes and eatery places most certainly in Hawaii, at other times in California, and occasionally in New York. Please understand that I feel completely inadequate in providing these acknowledgments. First and foremost, I wish to acknowledge God Almighty for His provisions and for giving me the strength to persevere in the pursuit of a vision. -

Bcustomary Land and Economic Development : Case Studies from Fiji

Copyright is owned by the Author of the thesis. Permission is given for a copy to be downloaded by an individual for the purpose of research and private study only. The thesis may not be reproduced elsewhere without the permission of the Author. ‘E da dravudravua e na dela ni noda vutuni-i-yau’ Customary land and economic development: case studies from Fiji. A thesis presented in fulfilment of the requirement of the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in Development Studies at Massey University Palmerston North Aotearoa Suliasi Davelevu Vunibola 2020 Abstract The purpose of this research is to determine how indigenous Fijian communities have been able to establish models of economic undertaking which allow successful business development while retaining control over their customary land and supporting community practices and values. External critics frequently emphasise that customary practices around land restrict economic development and undermine investments in the Pacific. There is also assertion that within the Pacific islands, culture and customary measures are mostly viewed as impediments of hopeful development. This research seeks to switch-over these claims by examining how customary land and measures facilitate successful business forms in Fiji. Along with the overarching qualitative methodology - a novel combination of the Vanua Research Framework, Tali Magimagi Research Framework, and the Bula Vakavanua Research Framework - a critical appreciative enquiry approach was used. This led to the development of the Uvi (yam - dioscorea alata) Framework which brings together the drauna (leaves) representing the capturing of knowledge, vavakada (stake) indicating the support mechanisms for indigenous entrepreneurship on customary land, uvi (yam tuber) signifying the indicators for sustainable development of indigenous business on customary land, and taking into consideration the external factors and community where the indigenous business is located. -

Colonial Uneven Development, Fijian Vanua, and Modern Ecotourism in Taveuni, Fijii

Colonial Uneven Development, Fijian Vanua, and Modern Ecotourism in Taveuni, Fijii Hao-Li Lin University of Pittsburgh Introduction This article is an attempt to situate the modern ecotourism ventures operated in the Bouma region of Taveuni today in the context of the island’s history of development from the pre-colonial times and the local Fijian communities’ vanua (land) identity. The main argument is that Bouma is a peripheral sphere, constructed by a series of events that contributed to a condition of “uneven development” (Harvey 2005:55-89; Smith 2008[1984]). The process was an intertwined history of land sale by the paramount chiefdom, establishment of large-scale plantations by foreign planters, and gazetting of nature reserves by the British colonial government from 1860 to 1914. These were further legalized by the colonial land tenure system and native policies. Although Bouma was seemingly left untouched in this history of land alienation and retained the majority of the native lands on Taveuni, the spatial dynamics of the island has been transformed and it became marginalized from the export-based plantation economy of Taveuni. The itaukei (natives) of Bouma do not see their environment in terms of capitalist production values. Believing themselves as the autochthonous people of the island, they seized the growing discourse of sustainable development and established their ecotourism projects in the 90s in the hope of uplifting their vanua identity, on which an indigenous blueprint of development resides. In this article, while concerning the expression of vanua in the Bouma region as a whole, I will focus on examples from Waitabu, one of the four main communities in Bouma.