Colonial Uneven Development, Fijian Vanua, and Modern Ecotourism in Taveuni, Fijii

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Resettlement of the Banabans in Rabi, Fiji Heart, and Do Not Be Many of You Will Already Be Thinking That My Working Life, Based As It Is in Stubborn Any Longer

“Circumcise ... your The resettlement of the Banabans in Rabi, Fiji heart, and do not be Many of you will already be thinking that my working life, based as it is in stubborn any longer. tropical Fiji, must be idyllic, and when my research takes me on site visits For the Lord your across tranquil seas to distant archipelagos, I think I may have lost all God is God of gods possible chance of convincing you otherwise. and Lord of lords, the great God, mighty Much of my work with the Pacific Conference of Churches (PCC) is focused and awesome, who is on climate change and the resettlement of at-risk peoples in Oceania. The not partial and takes region has over 200 coral atolls, all of which, scientists predict, are under no bribe, who threat from rising sea levels. Over the coming years, inhabitants of these executes justice for low-lying islands face relocation away from their atoll homes. the orphan and the widow, and who PCC wishes to offer advice and accompaniment to its member churches as loves the strangers, they support affected communities. Of all advocates involved in the providing them with resettlement task, the Church in the Pacific is physically as well as food and clothing. spiritually the closest to the community, and as such, it is ideally positioned You shall also love to help allay fears and relieve anxieties among those affected. the stranger…” Deuteronomy To be in active solidarity with the peoples of Oceania, PCC needs to be 10:16-19 (NRSV) aware of various accompaniment approaches, and to be able to offer suitable guidance where appropriate. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Tours & Activities

Tours & Activities Qamea and her neighboring islands offer a tropical paradise of adventure and beauty. Explore the island from the water on a sea-kayak or stand up paddleboard. Get up close and personal with the marine life with a beach snorkel into the kaleidoscopic world of our house reef. While you may ultimately decide to lounge the day away on the beach or by our swimming pool nestled in the jungle, if it is activities and adventure you seek, our staff will make sure you are as busy as you want to be... Below is a list of the inclusive resort activities available to you: Croquet Giant Chess Board Gym Island Walk Kayaks Snorkeling Stand Up Paddle Boards Swimming Pool Volleyball Badminton The Fijian culture is steeped in traditional values with a great deal of emphasis placed on family and religion. In order to share our beautiful culture with you, we offer a number of activities centered around the local Fijian way of life... Fijian Cooking Demonstration - Complimentary Join our talented food & beverage staff as they demonstrate how to make the famous traditional dish kokoda; a delicacy of fish, coconut milk and lime juice that has become a signature favorite on our menu. Village Visits - Complimentary For an inside look at traditional Fijian village life, join us as we visit one of the local villages on Qamea Island. Prior to departure, guests will be informed of the cultural protocol when entering a village, including modest dress standards. This is also an excellent place to purchase an authentic local handicraft souvenir from the displays mats in the community hall. -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Tuesday-27Th November 2018

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … 10 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 10-11 Point of Order … … … … … … … … … … 11-12 Debate on His Excellency the President’s Address … … … … … 12-68 List of Speakers 1. Hon. J.V. Bainimarama Pages 12-17 2. Hon. S. Adimaitoga Pages 18-20 3. Hon. R.S. Akbar Pages 20-24 4. Hon. P.K. Bala Pages 25-28 5. Hon. V.K. Bhatnagar Pages 28-32 6. Hon. M. Bulanauca Pages 33-39 7. Hon. M.D. Bulitavu Pages 39-44 8. Hon. V.R. Gavoka Pages 44-48 9. Hon. Dr. S.R. Govind Pages 50-54 10. Hon. A. Jale Pages 54-57 11. Hon. Ro T.V. Kepa Pages 57-63 12. Hon. S.S. Kirpal Pages 63-64 13. Hon. Cdr. S.T. Koroilavesau Pages 64-68 Speaker’s Ruling … … … … … … … … … 68 TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 The Parliament resumed at 9.36 a.m., pursuant to adjournment. HONOURABLE SPEAKER took the Chair and read the Prayer. PRESENT All Honourable Members were present. MINUTES HON. LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT IN PARLIAMENT.- Madam Speaker, I move: That the Minutes of the sittings of Parliament held on Monday, 26th November 2018, as previously circulated, be taken as read and be confirmed. HON. A.A. MAHARAJ.- Madam Speaker, I beg to second the motion. Question put Motion agreed to. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome I welcome all Honourable Members to the second sitting day of Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 session. -

The Diversity of Fijian Polities

7 The Diversity of Fijian Polities An overall discussion of the general diversity of traditional pan-Fijian polities immediately prior to Cession in 1874 will set a wider perspective for the results of my own explorations into the origins, development, structure and leadership of the yavusa in my three field areas, and the identification of different patterning of interrelationships between yavusa. The diversity of pan-Fijian polities can be most usefully considered as a continuum from the simplest to the most complex levels of structured types of polity, with a tentative geographical distribution from simple in the west to extremely complex in the east. Obviously I am by no means the first to draw attention to the diversity of these polities and to point out that there are considerable differences in the principles of structure, ranking and leadership between the yavusa and the vanua which I have investigated and those accepted by the government as the model. G.K. Roth (1953:58–61), not unexpectedly as Deputy Secretary of Fijian Affairs under Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, tended to accord with the public views of his mentor; although he did point out that ‘The number of communities found in a federation was not the same in all parts of Fiji’. Rusiate Nayacakalou who carried out his research in 1954, observed (1978: xi) that ‘there are some variations in the traditional structure from one village to another’. Ratu Sukuna died in 1958, and it may be coincidental that thereafter researchers paid more emphasis to the differences I referred to. Isireli Lasaqa who was Secretary to Cabinet and Fijian Affairs was primarily concerned with political and other changes in the years before and after independence in 1970. -

Current and Future Climate of the Fiji Islands

Rotuma eef a R Se at re Ahau G p u ro G a w a Vanua Levu s Bligh Water Taveuni N a o Y r th er Koro n La u G ro Koro Sea up Nadi Viti Levu SUVA Ono-i-lau S ou th er n L Kadavu au Gr South Pacific Ocean oup Current and future climate of the Fiji Islands > Fiji Meteorological Service > Australian Bureau of Meteorology > Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) Fiji’s current climate Across Fiji the annual average temperature is between 20-27°C. Changes Fiji’s climate is also influenced by the in the temperature from season to season are relatively small and strongly trade winds, which blow from the tied to changes in the surrounding ocean temperature. east or south-east. The trade winds bring moisture onshore causing heavy Around the coast, the average night- activity. It extends across the South showers in the mountain regions. time temperatures can be as low Pacific Ocean from the Solomon Fiji’s climate varies considerably as 18°C and the average maximum Islands to east of the Cook Islands from year to year due to the El Niño- day-time temperatures can be as with its southern edge usually lying Southern Oscillation. This is a natural high as 32°C. In the central parts near Fiji (Figure 2). climate pattern that occurs across of the main islands, average night- Rainfall across Fiji can be highly the tropical Pacific Ocean and affects time temperatures can be as low as variable. On Fiji’s two main islands, weather around the world. -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Fijian Colonial Experience: a Study of the Neotraditional Order Under British Colonial Rule Prior to World War II, by Timothy J

Chapter 4 The new of The more able Fij ian chiefs did not need to fetch up the glory of their ancestors to maintain leadership of their people: they exploited a variety of opportunities open to them within the Fij ian Administration. Ultimately colonial rule itself rested on the loyalty chosen chiefs could still command from their people, and day-to-day village governance, it has been seen, totally depended on them. Far from degenerating into a decadent elite, these chiefs devised a mode of leadership that was neither traditional, for it needed appointment from the Crown, nor purely administrative. Its material rewards came from salary and fringe benefits; its larger satisfactions from the extent to which the peopl e rallied to their leadership and voluntarily participated in the great celebrations of Fijian life , the traditional-type festivals of dance, food and ceremony that proclaimed to all: the people and the chief and the land are one . 'Government-work' had its place, but for chiefs and people there were always 'higher' preoccupations growing out of the refined cultural legacy of the past (albeit the attenuated past) which gave them all that was still distinctively Fij ian in their threatened way of life. This chapter will illuminate the ambiguous mix of constraint and opportunity for chiefly leadership in the colonial context as exercised prior to World War II by some powerful personalities from different status levels in the neotraditional order. Thurston's enthusiastic tax gatherer, Ratu Joni Madraiwiwi , was perhaps the most able of them , and in his happier days was generally esteemed as one of the finest of 'the old school' of chiefs . -

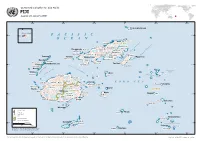

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

P a C I F I C O C E

OCHA Regional Office for Asia Pacific FIJI Issued: 20 January 2008 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W Thikombia Island 177° Nalele Rotuma Island 16°S PACIFIC 16°S 12°30’ Rotuma Sumi OCEAN Namukalau Nambouono Vunivatu NORTHERN Nanduri Namboutini Nayarambale Napuka Yangganga Navindamu Labasa Nailou Yangganga Rabi Channel Korotasere Nakarambo Savu Sau Nawailevu Taveun i Mate i Vanuabalavu Riqold Channel Mbangasau t i Matei Yasawa a Yandua r Nggamea Vanua Levu t Qeleni Cicia S Ndenimanu o Nacula Ndaria o m o s Waiyevo Navotua Waisa m S o Matacawalevu Matathawa Levu Rave-rave Taveuni 17°S Yaqeta VATU-I-RA CHANNELThavanga 17°S Somosomo Navakawau UP RO Naviti G A W A EXPLORING S Waya S ISLES A Y Koro Nalauwaki NORT Thikombia BLIGH WATER Togow ere Koro HERN LAU Tavua Makongai GRO Nasau UP Nayavutoka Vanuakula Lautoka Navala Navai Ovalau KORO SEA Bureta Levuka Tu vu th a Tuvutha Mala WESTERN Nayavu Lawaki Malololailai Nadi Wairuarua Lovoni Bukuya Nairai Malolo Vunindawa Saweni Korovou EASTERN Momi Viti Levu CENTRAL Narewa Dromuna Ngau 18°S Naraiyawa Nayau Liku 18°S Namosi Nausori Bega Ngau Sigatoka Navua Vatukarasa SUVA e Levuka Lakemba ssag Pa qa Vanuavatu Be Waisomo Mbengga National Capital City, Town Moala Moala Major Airport River Namuka Llau Provincial Boundary Namuka International Boundary Vabea 0 20 40 Kilometers Kandavu 19°S Soso 19°S Nukuvou SOUTHERN LAU GROUP 0 20 40 Miles Kandavu Fulanga Ongea Projection: World Cylindrical Equal Area Nasau Andako Matuku Monothaki Map data sources: Global Discovery, FAO 177°E 178°E 179°E 180° 179°W 178°W The names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Map Ref: OCHA_FJI_Country_v1_080120.