An Anthropological Study of Iraqis in the UK Zainab Saleh Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requireme

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorm Fire Rousts Students Draft Opposers Stage Rally; One Of

Spartan Daily Volume 72, Number 57 Serving the San Jose State Community Since 1934 Wednesday, May 2, 1979 A Draft opposers stage rally; RESIST One of 50 around the U.S. THE By Phetsy Calloway Approximately 50 persons at- speech to the audience. A small and passive group tended the SJSU rally. Many of "With mandatory conscription, converged on San Antonio and Third them, when asked, did say they were it will be very easy to fall back on DRAFT streets at noon yesterday to take opposed to revival of the draft. military aggression to solve foreign part in a rally against the draft. Four policemen were present policy problems," Ryan said. "I The rally was one of 50 staged watching the group, but were mainly think it's our responsibility to say, around the U.S. yesterday by occupied talking among themselves- not only as students but as citizens, students for a Libertarian Society. -easily not tersely, as their fellow we're not willing to let them do this. The rallies are being held 13 days to officers did at anti-draft demon- While we're willing to accept our the cut-off date for budget ap- strations during the Vietnam era. responsibilities, we're not willing to propriations needed to revive the There was little interaction of fight someone else's war." Selective Service. the audience with the speakers. A.S. Attorney-General elect .., coo A Eight bills are pending in "We stand today with seven bills Celio Ulcer() also addressed the DINT.41AN Congress which would revive some sailing through Congress which will rally. -

Offprint From: Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, Fifth Series, 9: 89-116

Offprint from: Journal of the Gypsy Lore Society, fifth series, 9: 89-116. 1999. JOHANN RÜDIGER AND THE STUDY OF ROMANI IN 18TH CENTURY GERMANY Yaron Matras University of Manchester Abstract Rüdiger’s contribution is acknowledged as an original piece of empirical research As the first consice grammatical description of a Romani dialect as well as the first serious attempt at a comparative investigation of the language, it provided the foundation for Romani linguistics. At the same time his work is described as largely intuitive and at times analytically naive. A comparison of the linguistic material is drawn with other contemporary sources, highlighting the obscure origin of the term ‘Sinte’ now used as a self-appellation by Romani-speaking populations of Germany and adjoining regions. 1. Introduction Several different scholars have been associated with laying the foundations for Romani linguistics. Among them are August Pott, whose comparative grammar and dictionary (1844/1845) constituted the first comprehensive contribution to the language, Franz Miklosich, whose twelve-part survey of Romani dialects (1872-1889) was the first contrastive empirical investigation, and John Sampson, whose monograph on Welsh Romani (1926) is still looked upon today as the most focused and systematic attempt at an historical discussion of the language. Heinrich Grellmann is usually given credit for disseminating the theory of the Indian origin of the Romani language, if not for discovering this origin himself. It is Grellmann who is cited at most length and most frequently on this matter. Rüdiger’s contribution from 1782 entitled Von der Sprache und Herkunft der Zigeuner aus Indien (‘On the language and Indian origin of the Gypsies’), which preceded Grellmann’s book, is usually mentioned only in passing, perhaps since it has only recently become more widely available in a reprint (Buske Publishers, Hamburg, 1990) and only in the German original, printed in old German characters. -

21St Century Exclusion: Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in European

Angus Bancroft (2005) Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in Europe: Modernity, Race, Space and Exclusion, Aldershot: Ashgate. Contents Chapter 1 Europe and its Internal Outsiders Chapter 2 Modernity, Space and the Outsider Chapter 3 The Gypsies Metamorphosed: Race, Racialization and Racial Action in Europe Chapter 4 Segregation of Roma and Gypsy-Travellers Chapter 5 The Law of the Land Chapter 6 A Panic in Perspective Chapter 7 Closed Spaces, Restricted Places Chapter 8 A ‘21st Century Racism’? Bibliography Index Chapter 1 Europe and its Internal Outsiders Introduction From the ‘forgotten Holocaust’ in the concentration camps of Nazi controlled Europe to the upsurge of racist violence that followed the fall of Communism and the naked hostility displayed towards them across the continent in the 21st Century, Europe has been a dangerous place for Roma and Gypsy-Travellers (‘Gypsies’). There are Roma and Gypsy-Travellers living in every country of Europe. They have been the object of persecution, and the subject of misrepresentation, for most of their history. They are amongst the most marginalized groups in European society, historically being on the receiving end of severe racism, social and economic disadvantage, and forced population displacement. Anti-Gypsy sentiment is present throughout Europe, in post-Communist countries such as Romania, in social democracies like Finland, in Britain, in France and so on. Opinion polls consistently show that they are held in lower esteem than other ethnic groups. Examples of these sentiments in action range from mob violence in Croatia to ‘no Travellers’ signs in pubs in Scotland. This book will examine the exclusion of Roma and Gypsy-Travellers in Europe. -

WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982

AUSTRALIAN RECORD LABELS WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS 1970 to 1982 COMPILED BY MICHAEL DE LOOPER © BIG THREE PUBLICATIONS, APRIL 2019 WARNER BROS. / WEA RECORDS, 1970–1982 A BRIEF WARNER BROS. / WEA HISTORY WIKIPEDIA TELLS US THAT... WEA’S ROOTS DATE BACK TO THE FOUNDING OF WARNER BROS. RECORDS IN 1958 AS A DIVISION OF WARNER BROS. PICTURES. IN 1963, WARNER BROS. RECORDS PURCHASED FRANK SINATRA’S REPRISE RECORDS. AFTER WARNER BROS. WAS SOLD TO SEVEN ARTS PRODUCTIONS IN 1967 (FORMING WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS), IT PURCHASED ATLANTIC RECORDS AS WELL AS ITS SUBSIDIARY ATCO RECORDS. IN 1969, THE WARNER BROS.-SEVEN ARTS COMPANY WAS SOLD TO THE KINNEY NATIONAL COMPANY. KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL (LATER CHANGING ITS NAME TO WARNER COMMUNICATIONS) COMBINED THE OPERATIONS OF ALL OF ITS RECORD LABELS, AND KINNEY CEO STEVE ROSS LED THE GROUP THROUGH ITS MOST SUCCESSFUL PERIOD, UNTIL HIS DEATH IN 1994. IN 1969, ELEKTRA RECORDS BOSS JAC HOLZMAN APPROACHED ATLANTIC'S JERRY WEXLER TO SET UP A JOINT DISTRIBUTION NETWORK FOR WARNER, ELEKTRA, AND ATLANTIC. ATLANTIC RECORDS ALSO AGREED TO ASSIST WARNER BROS. IN ESTABLISHING OVERSEAS DIVISIONS, BUT RIVALRY WAS STILL A FACTOR —WHEN WARNER EXECUTIVE PHIL ROSE ARRIVED IN AUSTRALIA TO BEGIN SETTING UP AN AUSTRALIAN SUBSIDIARY, HE DISCOVERED THAT ONLY ONE WEEK EARLIER ATLANTIC HAD SIGNED A NEW FOUR-YEAR DISTRIBUTION DEAL WITH FESTIVAL RECORDS. IN MARCH 1972, KINNEY MUSIC INTERNATIONAL WAS RENAMED WEA MUSIC INTERNATIONAL. DURING THE 1970S, THE WARNER GROUP BUILT UP A COMMANDING POSITION IN THE MUSIC INDUSTRY. IN 1970, IT BOUGHT ELEKTRA (FOUNDED BY HOLZMAN IN 1950) FOR $10 MILLION, ALONG WITH THE BUDGET CLASSICAL MUSIC LABEL NONESUCH RECORDS. -

Iraq Ten Years On’ Conference and at the Suleimani Forum at the American University of Suleimaniya, Both in March 2013

Iraq on the International Stage Iraq on the International Stage Foreign Policy and National Jane Kinninmont, Gareth Stansfield and Omar Sirri Identity in Transition Jane Kinninmont, Gareth Stansfield and Omar Sirri July 2013 Chatham House, 10 St James’s Square, London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0)20 7957 5700 E: [email protected] F: +44 (0)20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration Number: 208223 Iraq on the International Stage Foreign Policy and National Identity in Transition Jane Kinninmont, Gareth Stansfield and Omar Sirri July 2013 © The Royal Institute of International Affairs, 2013 Chatham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs) is an independent body which promotes the rigorous study of international questions and does not express opinions of its own. The opinions expressed in this publication are the responsibility of the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Please direct all enquiries to the publishers. Chatham House 10 St James’s Square London SW1Y 4LE T: +44 (0) 20 7957 5700 F: + 44 (0) 20 7957 5710 www.chathamhouse.org Charity Registration No. 208223 ISBN 978 1 86203 292 7 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Cover image: © Getty Images/AFP Designed and typeset by Soapbox Communications Limited www.soapbox.co.uk Printed -

Music & Entertainment

Hugo Marsh Neil Thomas Forrester Director Shuttleworth Director Director Music & Entertainment Tuesday 17th & Wednesday 18th November 2020 at 10:00 Viewing on a rota basis by appointment only For enquires relating to the Special Auction Services auction, please contact: Plenty Close Off Hambridge Road NEWBURY RG14 5RL Telephone: 01635 580595 Email: [email protected] www.specialauctionservices.com David Martin Dave Howe Music & Music & Entertainment Entertainment Due to the nature of the items in this auction, buyers must satisfy themselves concerning their authenticity prior to bidding and returns will not be accepted, subject to our Terms and Conditions. Additional images are available on request. Buyers Premium with SAS & SAS LIVE: 20% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 24% of the Hammer Price the-saleroom.com Premium: 25% plus Value Added Tax making a total of 30% of the Hammer Price 4. Touch LP, Touch - Original UK 10. Progressive Rock LPs, twelve DAY ONE Mono Release 1969 on Deram (DML 1033) albums of mainly Classic and Prog - With Poster - Laminated Gatefold Garrod Rock comprising The Who (Tommy and & Lofthouse Sleeve - Original Mono Inner Quadrophenia), Led Zeppelin II, Deep Vinyl Records - Brown / White Labels - Sleeve, Poster, Purple (Burn and Concerto For Group and Inner and Vinyl all in Excellent condition Orchestra), Black Sabbath - Sabbath Bloody A large number of the original albums £60-100 Sabbath, Pink Floyd - Ummagumma, David and singles in the Vinyl section make Bowie - 1980 All Clear (Promo), Osibisa -

Democratization After Iraq: Expatriate Perspectives on New British Agendas in the Arab Middle East

Democratization after Iraq: Expatriate Perspectives on new British agendas in the Arab Middle East Zoe Holman The University of Melbourne * BRISMES Graduate Section Annual Conference 2012 NB This paper forms part of a broader PhD study on the evolution of British democratisation policy in the Arab MENA since 2003, examining the contribution of Arab expatriates to foreign-policy development in their countries of origin. The thesis will discuss British policy interventions through four case studies - Iraq, Libya, Bahrain and Syria, and the findings in this project are based on the outcome of interviews conducted with diaspora from those countries in Britain in 2011-12. ‘Politically too, we rushed into the business with our usual disregard for a comprehensive political scheme. The real difficulty here is that we don't know exactly what we intend to do in this country. Can you persuade people to take your side when you are not sure in the end whether you'll be there to take theirs? It would take a good deal of potent persuasion to make them think that your side and theirs are compatible.’ - Gertrude Bell, Diaries, Basra 19161 'Our forces are friends and liberators of the Iraqi people, not conquerors. And they will not stay in Iraq a day longer than is necessary. I know from my meetings with Iraqi exiles in Britain that you are an inventive, creative people. It is in the spirit of friendship and goodwill that we now offer our help.’ - Tony Blair, Speech to the people of Iraq, 10 April 2003 Introduction On 7 April, 2002, a year to date before Coalition forces meted out the last blows to the fall of Saddam Hussein’s Baghdad, then British Prime Minister Tony Blair was delivering a speech at the Presidential library in the home state of American President George Bush. -

Gesamtliste Alben Mit Kategorie

Update Alben MP 3 nach MP3-Kategorie VBR Bitrate Interpreten - International Cohn, Marc Marc Cohn 0 16 Bit Creedence Clearwater Revival Inaxycvgtgb 192 Bayou Country 160 A la Carte Chooglin' 160 The very best '99 192 Creedence Clearwater Revival 160 Ace of base Creedence Country 160 The Singles 192 Green River 160 Anastacia Willy and the poor boys 0 Pieces of a dream 0 Doors, The Aphrodite's child The Look behind Collection (2 CD) 0 666 (2 CD) 192 Eagles Arabesque Eagles 0 Arabesque I 192 Eloy Arabesque II 192 Chronicles Vol. 1 0 Arabesque III 192 Chronicles Vol. 2 0 Arabesque IV 192 Colours 256 Beatles, The Dawn 224 The alternate Sgt. Pepper's 128 Destination 128 Bee Gees Eloy 192 Horizontal 224 Floating 192 Ideo 224 Inside 224 Odessa 224 Live 0 Tales from the Brothers Gibb (4 CD) 0 Metromania 0 Black Ocean II 128 Wonderful life 192 Performance 128 Boney M. Planets 0 Remix 2005 0 Power And The Passion 192 Brightman, Sarah Ra 0 Dive 256 Silent Cries & Mighty Echoes 192 Eden 256 Time to turn 192 Love changes everything 0 Timeless Passages (Best of Eloy) (2 CD) 192 Timeless 192 Emerson, Lake & Palmer Brooks, Garth Love Beach 0 In Pieces 0 Pictures At An Exhibition (Remastered) 0 Brown, Chuck & Cassidy, Eva Erasure The other side 160 Pop! (The first 20 Hits) 0 Bublé, Michael Faithfull, Marianne Michael Bublé 192 A perfect stranger (2 CD) 0 Cassidy, Eva Far Corporation Eva by heart 160 Division One 0 Imagine 0 Fine Young Cannibals Live at Blues Alley 160 The raw and the cooked 0 Method Actor 256 Fleetwood Mac No boundaries 256 The Blues Years 192 Songbird 128 Gibb, Robin Time after time 128 Secret agent 256 Clapton, Eric Golden Earring There's One In Every Crowd 256 2nd Live (2 CD) 192 Cocker, Joe Buddy Joe 0 Night calls 0 Contraband 192 One night of sin 0 Cut 192 Organic 0 Golden Earring 192 Montag, 12. -

Romani Worlds

ROMANI WORLDS: ACADEMIA, POLICY, AND MODERN MEDIA A selection of articles, reports, and discussions documenting the achievements of the European Academic Network on Romani Studies Edited by Eben Friedman / Victor A. Friedman Romani worlds: Academia, policy, and modern media A selection of articles, reports, and discussions documenting the achievements of the European Academic Network on Romani Studies Edited by Eben Friedman and Victor A. Friedman Cluj-Napoca: Editura Institutului pentru Studierea Problemelor Minorităţilor Naţionale, 2015 ISBN: 978-606-8377-40-7 Design: Marina Dykukha Layout: Sütő Ferenc Photos: László Fosztó, Network Secretary, unless other source is indicated © Council of Europe and the contributors The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe or the European Commission. 2 CONTENTS CONTENTS INTRODUCTION TO THE VOLUME __________________________________________ 6 Eben Friedman, Victor A. Friedman with Yaron Matras PART ONE: THE STRASBOURG SHOWCASE EVENT ____________________________ 11 Edited by Eben Friedman with Victor A. Friedman Opening statement by Ágnes Dároczi (European Roma and Travellers Forum) _______ 12 Opening statement by Eben Friedman (European Centre for Minority Issues) ________ 18 Opening statement by Margaret Greenfields Buckinghamshire( New University) _____ 24 Europe’s neo-traditional Roma policy: Marginality management and the inflation of expertise ____________________________________________ 29 Yaron Matras The educational and school inclusion of Roma in Cyprus and the SEDRIN partners’ country consortium _______________________________ 48 Loizos Symeou 3 CONTENTS PART TWO: EMAIL DISCUSSIONS _________________________________________ 72 Edited by Eben Friedman and Victor A. Friedman, with Judit Durst Network Discussion 1: Measuring and reporting on Romani populations ___________ 74 Edited by Eben Friedman with Victor A. -

Rock Album Discography Last Up-Date: September 27Th, 2021

Rock Album Discography Last up-date: September 27th, 2021 Rock Album Discography “Music was my first love, and it will be my last” was the first line of the virteous song “Music” on the album “Rebel”, which was produced by Alan Parson, sung by John Miles, and released I n 1976. From my point of view, there is no other citation, which more properly expresses the emotional impact of music to human beings. People come and go, but music remains forever, since acoustic waves are not bound to matter like monuments, paintings, or sculptures. In contrast, music as sound in general is transmitted by matter vibrations and can be reproduced independent of space and time. In this way, music is able to connect humans from the earliest high cultures to people of our present societies all over the world. Music is indeed a universal language and likely not restricted to our planetary society. The importance of music to the human society is also underlined by the Voyager mission: Both Voyager spacecrafts, which were launched at August 20th and September 05th, 1977, are bound for the stars, now, after their visits to the outer planets of our solar system (mission status: https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/mission/status/). They carry a gold- plated copper phonograph record, which comprises 90 minutes of music selected from all cultures next to sounds, spoken messages, and images from our planet Earth. There is rather little hope that any extraterrestrial form of life will ever come along the Voyager spacecrafts. But if this is yet going to happen they are likely able to understand the sound of music from these records at least. -

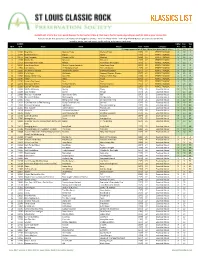

KLASSICS LIST Criteria

KLASSICS LIST criteria: 8 or more points (two per fan list, two for U-Man A-Z list, two to five for Top 95, depending on quartile); 1984 or prior release date Sources: ten fan lists (online and otherwise; see last page for details) + 2011-12 U-Man A-Z list + 2014 Top 95 KSHE Klassics (as voted on by listeners) sorted by points, Fan Lists count, Top 95 ranking, artist name, track name SLCRPS UMan Fan Top ID # ID # Track Artist Album Year Points Category A-Z Lists 95 35 songs appeared on all lists, these have green count info >> X 10 n 1 12404 Blue Mist Mama's Pride Mama's Pride 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 1 2 12299 Dead And Gone Gypsy Gypsy 1970 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 2 3 11672 Two Hangmen Mason Proffit Wanted 1969 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 5 4 11578 Movin' On Missouri Missouri 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 6 5 11717 Remember the Future Nektar Remember the Future 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 7 6 10024 Lake Shore Drive Aliotta Haynes Jeremiah Lake Shore Drive 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 9 7 11654 Last Illusion J.F. Murphy & Salt The Last Illusion 1973 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 12 8 13195 The Martian Boogie Brownsville Station Brownsville Station 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 13 9 13202 Fly At Night Chilliwack Dreams, Dreams, Dreams 1977 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 14 10 11696 Mama Let Him Play Doucette Mama Let Him Play 1978 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 15 11 11547 Tower Angel Angel 1975 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 19 12 11730 From A Dry Camel Dust Dust 1971 27 PERFECT KLASSIC X 10 20 13 12131 Rosewood Bitters Michael Stanley Michael Stanley 1972 27 PERFECT -

Spillelisting”

”Spillelisting” En kvalitativ undersøkelse av strømmebrukeres omgang med spillelister som aktiv prosess Henrik Sanne Kristensen Masteroppgave ved Institutt for medier og kommunikasjon UNIVERSITETET I OSLO 01.06.2014 I © Henrik Sanne Kristensen 2014 ”Spillelisting - En kvalitativ undersøkelse av strømmebrukeres omgang med spillelister som aktiv prosess” Henrik Sanne Kristensen http://www.duo.uio.no Trykk: Reprosentralen, Universitetet i Oslo II III Sammendrag I denne oppgaven undersøker jeg hvordan brukere av strømmetjenestene Spotify og WiMP benytter seg av spillelister i det daglige. Åtte informanter har gjennom tre perioder med online-dagbøker delt sine opplevelser og erfaringer ved bruk av spillelister, og således forsynt oppgaven med et unikt innblikk i flere viktige sider ved hverdagsanvendelse. Basert på disse dagboknoteringene, i tillegg til kvalitative intervjuer og Last.fm-innsyn, har jeg analysert hva som vektlegges når spillelister benyttes i det daglige. Gjennom fire analysekapitler tar jeg for meg informantenes ulike strategier og motivasjoner for å benytte spillelister. Jeg forklarer hvordan informantenes omgang med lister på flere ulike måter preges av en dynamisk og aktiv bruk. En annen observasjon dreier seg om informantenes pågående arbeid med spillelister, og hvordan prosessen spillelisting er sentral. Dessuten kommer det også frem at spillelister, slik vi er fortrolig med dem fra strømmetjenestene, skiller seg fra en del tidligere spillelistepraksiser, i at de kjennetegnes av tydelige sosiale og kommunikative kvaliteter. De tre hovedfunnene jeg gjør rede for beskriver spillelistekompilering som en lystbetont prosess; at spillelister lages ut fra uegennyttige hensyn og at listene kan sees på som sosiale og kommunikative medium; og til slutt at spillelistenes flytende kvaliteter kan ses i lys av en større, mer overordnet endring av musikkulturen de senere årene.