Hovedoppgave.Pdf (647.7Kb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sunshine Thoughts

S P I R I T U S – Z o o m Seminars for the Sensitive Sunshine Thoughts ALL COURSES THROUGH ZOOM Bookings Email: [email protected] Minister Matthew Smith www.matthewinspires.co.uk Challenges or This life is a schoolroom of opportunity, and we are both Opportunities? teacher and student. We never stop learning. There are even Life presents us with experiences daily. times we must unlearn to Some are not as “challenging as others” learn. How we approach the situation is vital. We are spirit with a physical On The Horizon The word “challenges” if replaced with body not a physical body with a “opportunities” gives a completely spirit with all experience having Its mid-June and Mother Nature different focus. Just changing one word value and worth for spiritual is painting our surroundings with does not change the given situation but progression. Not always easy to colour and beauty. Wildlife is perspective. Spiritualism teaches us that accept particularly when we everywhere and we can see the the mind is the builder and as we think we allow the emotions to take us importance of Nature in our become. Thousands of years ago in one of out of our power. As sensitives lives. Until a few years ago I the temples in Delphi, the inscription when we become overly never had interest in my garden. “Know thyself” was written on the wall. emotional it detaches us from It was in my reality a space That simple philosophy is as true today as our life force. This always attached to the house. -

A Lawyer Presents the Case for the Afterlife

A Lawyer Presents the Case for the Afterlife Victor James Zammit 2 Acknowledgements: My special thanks to my sister, Carmen, for her portrait of William and to Dmitri Svetlov for his very kind assistance in editing and formatting this edition. My other special thanks goes to the many afterlife researchers, empiricists and scientists, gifted mediums and the many others – too many to mention – who gave me, inspiration, support, suggestions and feedback about the book. 3 Contents 1. Opening statement............................................................................7 2. Respected scientists who investigated...........................................12 3. My materialization experiences....................................................25 4. Voices on Tape (EVP).................................................................... 34 5. Instrumental Trans-communication (ITC)..................................43 6. Near-Death Experiences (NDEs) ..................................................52 7. Out-of-Body Experiences ..............................................................66 8. The Scole Experiment proves the Afterlife ................................. 71 9. Einstein's E = mc2 and materialization.........................................77 10. Materialization Mediumship.......................................................80 11. Helen Duncan................................................................................90 12. Psychic laboratory experiments..................................................98 13. Observation -

Energy Fields – General Page 1 of 11

25.0 Energy Fields – General Page 1 of 11 25.0: Energy Fields - General Every object, whether living or inanimate, is comprised of atoms and is therefore endowed with an energy field. This field is a collective expression of all the individual atomic fields contained within the object. It has been known for thousands of years that crystals emit energy at different frequencies which will affect the human body in different ways: 1 The first historical references to the use of crystals come from the Ancient Sumerians, who included crystals in magic formulas. The Ancient Egyptians used lapis lazuli, turquoise, carnelian, emerald and clear quartz in their jewellery. They also carved grave amulets of the same gems. The Ancient Egyptians used stones primarily for protection and health. The human body, too, being constructed from atomic particles, has an energy field which is readily detectable both by other sensitive people and machines built for that specific purpose. This field which exists around each human being has many names; usually the ‘Aura’ or ‘Human Energy Field’. Of this field the spiritual healer and author Barbara Ann Brennan notes: 2 There are many systems that people have created from their observations to define the auric field. All these systems divide the aura into layers and define the layers by locations, colour, brightness, form, density, fluidity and function. Each system is geared to the kind of work the individual is "doing" with the aura. The two systems most similar to mine are the ones used by Jack Schwarz, which has more than seven layers and is described in his book, Human Energy Systems, and the system used by Rev. -

To Download for FREE

FREE | SEPTEMBER 2020 ESTABLISHED IN 1932 incorporating Two Worlds NEW SURVEY LAUNCHED INTO THE AFTERLIFE WISDOM FROM THE LAND OF LIFTING THE LOCKDOWN LOVE AND LIGHT BEYOND AS CHURCHES START TO REOPEN TABLE ‘TALKS’ WITH WE ALL HAVE THE DIVINE FAMOUS ‘DEAD’ AUTHOR SPARK WITHIN US SEPARATED TWINS LEARN THE ART OF REUNITED AFTER PSYCHOMETRY CHANCE ENCOUNTER ARTHUR FINDLAY ‘I’M A CELEBRITY…’ WILL BE COLLEGE PLANS BASED IN HAUNTED CASTLE RUSSIAN WEEK HOSPITAL GARDEN HELPS THERAPY DOG NOMINATED EXPLORER TO RECOVER FOR HEALTH HERO AWARD FROM CORONAVIRUS DIALOGUE WITH HEAVEN KYLE’S CARDS HAVE ISSUE NO 4192 ANGELIC ANGLE Contents 05 Two Worlds Are One Amongst various topics, Tony Ortzen tells how being in space had a profound effect on an astronaut, and 22 TV presenter Paul O’Grady describes seeing UFOs 30 Lighthouses of the spirit Sit back and enjoy some wonderful 09 Lifting the lockdown as trance teachings from Silver Birch churches start to reopen 30 A report from Bournemouth 32 Learn the art of Spiritualist Church, which was amongst the first to open again after psychometry Therapy dog is lockdown restrictions were eased 16 Craig Hamilton-Parker features the nominated for Health fascinating field of psychometry Making premises safe Hero award 10 Environmental Health Officer Geoff A Cockapoo and her owner who 35 When the white Nunn outlines the steps taken to make visit intensive care units could win angel calls Bournemouth church safe, as the an award A truly inspirational funeral service COVID-19 pandemic continues from famous trance medium -

Get in Tune with a Positive Lifestyle

£3.80 | JUNE 2021 ESTABLISHED IN 1932 incorporating Two Worlds GET IN TUNE WITH A POSITIVE LIFESTYLE TOUR GUIDE URI SEEKS SHELTER SEES APPARITION FROM ROCKETS AT BUS STOP DIANA COOPER ON SCIENTISTS DISCOVER THE LOST LAND DEATH LEADS TO LIFE OF ATLANTIS COLLEGE LAUNCHES ‘DON’T GHOST HUNT MAJOR EXHIBITION OF ART, IN GRAVEYARDS’ SAYS ARTEFACTS AND BOOKS RESEARCHER SUPERMODEL IS TAKING A LOOK AT LIFE, CRYSTAL CLEAR ON LOCKDOWNS AND LOVE BENEFITS OF CRYSTALS FORMER ROMAN DOCTORS SAY CATHOLIC SPREADS ‘SPIRITUAL FITNESS’ SPIRIT TRUTHS MAY REDUCE RISK OF ALZHEIMER’S EXPERTS GIVE DISEASE PURRFECT ADVICE ON AROMATHERAPY FOR CATS ISSUE NO 4201 PSYCHIC NEWS ARCHIVES How to view every issue of Psychic News ever published, from 1932 to the present day! Issues of it in newspaper format, from 1932 to 2010, are now available online for FREE as a historic archive by the University of Manitoba at: https://libguides.lib.umanitoba.ca/psychicnews Every issue in its magazine format, from 2011 to the present day, can be viewed by website subscribers at: www.psychicnews.org.uk for just £26 for 1 year or £14 for 6 months 2 PSYCHIC NEWS | JUNE 2021 30 Experts give purrfect advice on aromatherapy Contents for cats Nayana Morag and Julie-Anne Thorne take an holistic approach 04 Two Worlds Are One 30 towards treating cats and Metal bender and motivational maintaining their health speaker Uri Geller tells of taking shelter as rockets land in Tel The lost land Aviv during the recent conflict. 34 Meanwhile, a famous author gives of Atlantis some sage advice on dealing -

PSYPIONEER JOURNAL Volume 9, No 03: March 2013

PSYPIONEER F JOURNAL Edited by Founded by Leslie Price Archived by Paul J. Gaunt Garth Willey EST Amalgamation of Societies Volume 9, No—~§~ 03:— March 2013 —~§~— 070 – A review of Voices in the Void by Hester (Dowden) Travers Smith by Maxine Meilleur 073 – Beyond the ‘Ectoplasmic Humerus’: The life and legacy of healer William Lilley By Maxine Meilleur 075 – Paul J. Gaunt Comments 076 – Police Ban a Spiritualist Meeting – It Would Break The Witchcraft Act! – Psychic News 080 – Banned Meeting Causes Laughter In House– Psychic News 084 – The Passing of the Rev. G. Vale Owen 087 – The Edwardian Afterlife Diary of Emma Holden – Book Review Paul J. Gaunt 088 – Spirits of the Trade: Teleplasm, Ectoplasm, Psychoplasm, Ideoplasm – Marc Demarest 099 – Some books we have reviewed 100 – How to obtain this Journal by email ============================= Please Note: Leslie Price retired from his previous work on March 25, and began work on April 2 as Archivist at the College of Psychic Studies in London. He will continue to be reachable on [email protected] Please check the e- mail addresses you have for him and delete any care of London Fire. 69 WHO’S AFRAID OF THE OUIJA- BOARD? Maxine Meilleur is a member of the SNUi and the Church of the Living Spirit in Lily Dale, New York. A frequent student at the Arthur Findlay College1 and summer resident of Lily Dale (the World’s longest continually run Spiritualist summer camp in the world), she practices mediumship during non-summer months remotely from her home in the Middle East. She wrote Khadija: The First Lady of Islam,2 an historical novel on the first wife of the Prophet Mohammed, in part by remote viewing her life and era. -

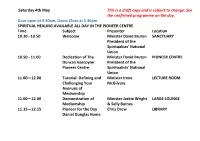

Saturday 4Th May Open Week Draft Programme

Saturday 4th May This is a draft copy and is subject to change. See the confirmed programme on the day. Door open at 9.30am, Doors Close at 5.30pm SPIRITUAL HEALING AVAILABLE ALL DAY IN THE PIONEER CENTRE Time Subject Presenter Location 10.30 –10.50 Welcome Minister David Bruton SANCTUARY President of the Spiritualists' National Union 10.50 - 11.00 Dedication of The Minister David Bruton PIONEER CENTRE Duncan Gascoyne President of the Pioneer Centre Spiritualists' National Union 11.00—12.00 Tutorial: Defining and Minister Irene LECTURE ROOM Challenging Your McGilvary Avenues of Mediumship 11.00—12.00 Demonstration of Minister Jackie Wright LARGE LOUNGE Mediumship & Sally Barnes 11.15—12.15 Pioneer for the Day Chris Drew LIBRARY Daniel Dunglas Home 12.15 - 1.15 Demonstration of Minister Colin Bates LECTURE ROOM Mediumship and Lynn Parker 11.30 - 12.30 Trance Demonstration Minister Judith Seaman SANCTUARY 12.30—1.30 An appointment with Libby Clarke OSNU LARGE LOUNGE Dr. James Trance Healing 12.30—1.30 The Saturday debate - Minister David R LIBRARY Search for the True Bruton, Minister Jackie message of Spiritualism Wright & John Blackwood OSNU 12.45—1.45 Demonstration of GORDON HIGGINSON SANCTUARY Mediumship Scholarship Students 1.30 - 2.30 Trance Healing Minister Steven Upton LECTURE ROOM Demonstration 2.45 - 3.45 Lecture: Shamanic soul Maureen Murnan LECTURE ROOM 2.00 - 300 Demonstration of Penny Hayward & Julie LIBRARY Mediumship Grist 2.15 - 315 "Branching out - Alv Hirst GARDEN Subject to philosophy to take us weather further.' 2.00—3.00 -

La Scienza Che Ha Dimostrato L'aldila'

FRANCESCA SCARRICA LA SCIENZA CHE HA DIMOSTRATO L’ALDILA’ 87 fra scienziati e brillanti ricercatori che hanno dimostrato la realtà della sopravvivenza dell’anima alla morte fisica 2008 © 2008 Francesca Scarrica E' vietata la riproduzione totale o parziale dei testi senza il consenso scritto dell'autore. ISBN 978-1-4092-0493-0 2 A tutti quegli scienziati coraggiosi e ai ricercatori appassionati che hanno dato il loro prezioso contributo alla ricerca delle prove dell’esistenza dell’aldilà 3 4 Introduzione Questo libro nasce da un apparente paradosso che, “nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita”, mi sono ritrovata a dover affrontare e risolvere per poter continuare a vivere un’esistenza nella quale ci fosse ancora spazio per concetti fondamentali quali la speranza e la gioia. Sono consapevole che questo tipo di percorso sia comune a tutti gli esseri umani che, prima o poi, si trovano a doversi porre le eterne questioni che riguardano la morte ed il modo di inquadrarla in una prospettiva che la possa rendere in qualche modo accettabile nella nostra concezione della vita e del mondo. Difatti quando perdiamo una persona cara tutti noi siamo costretti, volenti o nolenti, ad intraprendere quella fase incerta e dolorosa che gli psicologi chiamano “elaborazione del lutto”, un percorso difficile che la maggioranza di noi compie nella solitudine del proprio intimo, spesso senza riuscire a trovare il giusto supporto per alleviare il doloroso senso di perdita e affidandosi per lo più al tempo che passa considerandolo, come recita un vecchio detto, “un gran dottore”. Ma il rischio reale è che, col tempo, oltre al dolore, passi anche la voglia di vivere e di riamare. -

PSYPIONEER JOURNAL Volume 9, No 04: April 2013

PSYPIONEER F JOURNAL Edited by Founded by Leslie Price Archived by Paul J. Gaunt Garth Willey EST Amalgamation of Societies Volume 9,— No~§~— 04: April 2013 —~§~— 102 – Fraud & Psychical Research – Leslie Price 109 – From Home Shores to Far Horizons: Hester Dowden as a Child – Wendy Cousins 112 – New biography of Mrs Britten 114 – The Cathar View: The Mysterious Legacy of Montsegur (review) – Lynda Harris 117 – Henry Slade 1836c – 1905 117 – Dr. Slade’s Last Illness – Light 120 – Henry Slade: Spirit-Medium – Medium and Daybreak 127 – March 1866 – The Beginnings of Independent Slade-Writing – Marc Demarest 133 – Slate Written in Presence of Mr Slade – Britten Memorial Museum 134 – Some books we have reviewed 135 – How to obtain this Journal by email ============================= Please Note: Leslie Price retired from his previous work on March 25, and began work on April 2 as Archivist at the College of Psychic Studies in London. He will continue to be reachable on [email protected] Please check the e- mail addresses you have for him and delete any others. 101 FRAUD AND PSYCHICAL RESEARCH A lecture to Society for Psychical Research, London on Thursday 28 March 2013. [Note by Leslie Price: As the booked speaker about trickery for 28 March was unable to be present, I was invited to step in, and chose this related subject.] An experienced parapsychologist writes: “Fraud is not simply a minor (or major) irritant for researchers. Fraud is one key to understanding the nature of psi — and the nature of the paranormal generally. The connection of psi with deception is pervasive; thus any comprehensive theory of psi must explain its strong association with deception. -

To Download for FREE

FREE | AUGUST 2020 ESTABLISHED IN 1932 incorporating Two Worlds Items King sent to Spiritualist sell at auction for over £76,000 ORIGINS OF BELIEF CELEBRATING IN THE AFTERLIFE ACTS OF LOVE PAINTING AND ALL LIFE IS THE UNSEEN SPIRIT Hilma af Klint’s place in Lionel Owen shares some art history recognised thoughts prompted by with new documentary COVID-19 lockdowns WOMAN MYSTERY ‘MEETS’ SOLVED AT NORSE GOD STONEHENGE ‘DEAD’ GANDER’S RETURN REPLACING HATRED AND IS NO FLIGHT OF FANCY BIGOTRY WITH RESPECT BEYOND SCIENCE MOTHER RETURNS FICTION WITHIN MINUTES Mediums, professors and forensic tests offer powerful evidence of OF PASSING ON an atheist’s spirit return PSYCHIC NEWS | AUGUST 2020 ISSUE NO 411 91 20 Contents 05 Two Worlds Are One 15 ‘Dead’ gander’s return Editor Tony Ortzen homes in on is no flight of fancy several very different subjects, Medium Gina Lorraine Murray 28 Mother returns within including a comedian seeing his describes some of the pets who minutes of passing on “dead” stage partner have returned through her gift Let’s go Dutch and meet medium José Gosschalk from the 09 Woman ‘meets’ 18 Chess champion makes Netherlands Norse god right move buying A patient who underwent an out- 32 Beyond science fiction of-body experience encounters a bookshop Mediums, professors and forensic Norwegian god The owner of London’s oldest tests offer powerful evidence of mind, body and spirit bookshop an atheist’s spirit return tells how he turned the ailing 10 Items King sent to company around Spiritualist sell at 36 Origins of belief auction for over Singer has capital in the afterlife 20 Columnist Barbara White £76,000 encounter with discovers that humanity began to A letter and cigarette case King phantom theorise about an afterlife many George VI sent to his Spiritualist Robbie Williams outlines some of thousands of years ago. -

Voice and Evidence in Australian Spiritualism Matt Tomlinson

1 How to speak like a spirit medium: Voice and evidence in Australian Spiritualism Matt Tomlinson University of Oslo American Ethnologist, Volume 46 Issue 4 November 2019 For the published version, please see https://doi.org/10.1111/amet.12832 Abstract In the movement known as Spiritualism, successful performances of “mental mediumship” are rarely smooth. At services held by the Canberra Spiritualist Association, mediums attempt to provide evidence of life after death by describing a deceased person’s character in ways recognizable to audience members. A medium’s verbal performance de-emphasizes heteroglossia while developing vivid spirit characters. Audience members sometimes do not understand or accept what the medium says, but small “failures” in performance help build a larger sense that mediums and audiences are working to gather evidence. As they work, mediums foreground and background their agency at the same time, displaying their fluency in spirit communication while identifying spirits as ultimately responsible for being 2 present, and offering messages to the living. [ritual, dialogue, Spiritualism, mediumship, voice, evidence, Australia] When humans speak with gods, ghosts, demons, and other spirit beings, their talk often has the “coefficient of weirdness” that Bronislaw Malinowski (1966, 218) attributed to magical speech (see also Mauss 1972, 57–58). As they communicate with figures who generally cannot be seen and may be considered unpredictable, many people speak in ways that signal that something unusual is happening, their words prone to more than the usual slippages of interaction (Keane 1997a, 1997b, 2007, 2008). There are significant counterexamples of this tendency, however, in which people speak with and for extrahuman beings in relatively plain, everyday ways. -

An Investigation of Music and Paranormal Phenomena

PARAMUSICOLOGY: AN INVESTIGATION OF MUSIC AND PARANORMAL PHENOMENA Melvyn J. Willin Ph. D. Music Department University of Sheffield February 1999 IMAGING SERVICES NORTH Boston Spa, Wetherby West Yorkshire, LS23 7BQ www.bl.uk THESIS CONTAINS TAPE CASSETTE PARAMUSICOLOGY: AN INVESTIGATION OF MUSIC AND PARANORMALPBENOMENA Melvyn J. Willin SUMMARY The purpose of this thesis is to explore musical anomalies that are allegedly paranormal in origin. From a wide range of categories available, three areas are investigated: • music and telepathy • music written by mediums professedly contacted by dead composers • music being heard where the physical source of sound is unknown and presumed to be paranormal. In the first part a method of sensory masking (referred to as ganzfeld) is used to study the possibility of the emotional or physical content of music being capable of mind transference. A further experiment presents additional results relating to the highest scoring individuals in the previous trials. No systematic evidence for the telepathic communication of music was found. In the second section a number of mediums and the music they produced are investigated to examine the truthfulness of their claims of spiritual intervention in compositions and performances. Methods of composition are investigated and the music is analysed by experts. For the final part of the thesis locations are specified where reports of anomalous music have been asserted and people claiming to have heard such music are introduced and their statements examined. Literature from a variety of data bases is considered to ascertain whether the evidence for paranormal music consists of genuine material, misconceived perceptions or fraudulent claims.