Masks on the Move Defying Genres, Styles, and Traditions in the Cameroonian Grassfields

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ouest Uest E

quête d’assurance quête en transfrontaliers clients Les le Maire et son adjoint et son le Maire Kwemo Pierre fait enfermer ErnestOuandié honorent Patient etNdom Walla Kah Basile, Louka Adamou, Koupit Ouest Echos N° 1171 du 20 du 1171 N° Echos Ouest AFRILAND QUITTE GUINÉE LA EQUATO, LES PRODUCTEURS DE L’OUEST INQUIETS... Récipissé N°341 / RDDJ / C19 / BAPP DEVOIR DE MÉMOIRE : MÉMOIRE DE DEVOIR Since 1994 (vingt troisième année) O O COMMUNE DEBANWA COMMUNE PremierJournal national d’informations Régionales uest uest au 26 Janvier 2021 2021 Janvier 26 au l’arbitrage du Premier Ministre choix dusite et demandent Les populations s’opposent au première chaire Pierre Castel du pays L’Université deDschang hôte de la PARTENARIAT PRIVÉAU CAMEROUN PUBLIC PARTENARIAT CONSTRUCTION DU PEAGE AUTOMATIQUE DEBANDJA AUTOMATIQUE PEAGE DU CONSTRUCTION Tomaïno Ndam Njoya à Foumban à Njoya Ndam Tomaïno Awa se Fonka brûle au contact de E E INSTALLATION DU PRÉFET DU PRÉFET DU NOUN INSTALLATION Michel Eclador PEKOUA Eclador Michel publication de Directeur Les Monts d’Or 2020 2020 d’Or Monts Les Prix : 400 F. CFA F. 400 : Prix LA RÉGION DEL’OUEST RÉGION LA CÉLÈBRE SES AWARDS SES CÉLÈBRE c’est bientôt !!! bientôt c’est Actualités INSTALLATION DU NOUVEAU PRÉFET DU NOUN : Le gouverneur Awa Fonka perd sa sérénité à Foumban La scène a médusé les milliers de populations venus accueillir à la place des fêtes de Foumban, le nouveau préfet du département du Noun, Um Donacien, nommé le 18 décembre 2020 en remplacement de monsieur Boyomo Donatien, muté. l'occasion de la cérémonie de gramme de la plus leur temps à afficher leur mul- Njoya. -

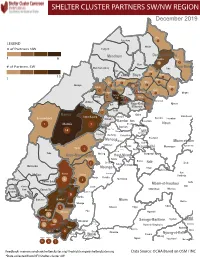

NW SW Presence Map Complete Copy

SHELTER CLUSTER PARTNERS SW/NWMap creation da tREGIONe: 06/12/2018 December 2019 Ako Furu-Awa 1 LEGEND Misaje # of Partners NW Fungom Menchum Donga-Mantung 1 6 Nkambe Nwa 3 1 Bum # of Partners SW Menchum-Valley Ndu Mayo-Banyo Wum Noni 1 Fundong Nkum 15 Boyo 1 1 Njinikom Kumbo Oku 1 Bafut 1 Belo Akwaya 1 3 1 Njikwa Bui Mbven 1 2 Mezam 2 Jakiri Mbengwi Babessi 1 Magba Bamenda Tubah 2 2 Bamenda Ndop Momo 6b 3 4 2 3 Bangourain Widikum Ngie Bamenda Bali 1 Ngo-Ketunjia Njimom Balikumbat Batibo Santa 2 Manyu Galim Upper Bayang Babadjou Malentouen Eyumodjock Wabane Koutaba Foumban Bambo7 tos Kouoptamo 1 Mamfe 7 Lebialem M ouda Noun Batcham Bafoussam Alou Fongo-Tongo 2e 14 Nkong-Ni BafouMssamif 1eir Fontem Dschang Penka-Michel Bamendjou Poumougne Foumbot MenouaFokoué Mbam-et-Kim Baham Djebem Santchou Bandja Batié Massangam Ngambé-Tikar Nguti Koung-Khi 1 Banka Bangou Kekem Toko Kupe-Manenguba Melong Haut-Nkam Bangangté Bafang Bana Bangem Banwa Bazou Baré-Bakem Ndé 1 Bakou Deuk Mundemba Nord-Makombé Moungo Tonga Makénéné Konye Nkongsamba 1er Kon Ndian Tombel Yambetta Manjo Nlonako Isangele 5 1 Nkondjock Dikome Balue Bafia Kumba Mbam-et-Inoubou Kombo Loum Kiiki Kombo Itindi Ekondo Titi Ndikiniméki Nitoukou Abedimo Meme Njombé-Penja 9 Mombo Idabato Bamusso Kumba 1 Nkam Bokito Kumba Mbanga 1 Yabassi Yingui Ndom Mbonge Muyuka Fiko Ngambé 6 Nyanon Lekié West-Coast Sanaga-Maritime Monatélé 5 Fako Dibombari Douala 55 Buea 5e Massock-Songloulou Evodoula Tiko Nguibassal Limbe1 Douala 4e Edéa 2e Okola Limbe 2 6 Douala Dibamba Limbe 3 Douala 6e Wou3rei Pouma Nyong-et-Kellé Douala 6e Dibang Limbe 1 Limbe 2 Limbe 3 Dizangué Ngwei Ngog-Mapubi Matomb Lobo 13 54 1 Feedback: [email protected]/ [email protected] Data Source: OCHA Based on OSM / INC *Data collected from NFI/Shelter cluster 4W. -

19/20 September 2020 Entry Lists

19/20 SEPTEMBER 2020 ENTRY LISTS Focus CUP ENDUROKA MONOPOSTO CHAMPIONSHIP 1800, 1600, CLASSIC & M1000 RACE 1 - 15 MINS (SAT), RACE 6 - 15 MINS (SAT) No. Driver Hometown Team/Sponsor Car CC Class TECH TALK 30 Andrew Cartmell Royston - Revelation 1000 1000 M1000 41 Billy Styles Cheshunt - Jedi Mk 6/7 1000 M1000 DESCRIPTION 53 Dan Clowes Newcastle-under-Lyme - Jedi Mk6 1000 M1000 The Monoposto Racing Club is a club 77 Nigel Davers Warminster Team Fern Racing Jedi Mk 6 1000 M1000 of motor sport enthusiasts promoting single seater motor racing in an inclusive, 78 Myles Castaldini Leamington Spa Tappex Thread Inserts Van Diemen RF94 1000 M1000 friendly and respectful environment 441 Chris Woodhouse Far Forest - Jedi Mk6 998 M1000 where the regulations promote stable, 19 Nick Catanzaro Whitminster - Formula Vauxhall Lotus 2000 Classic affordable and competitive racing. 25 Jim Spencer Cheshire - Reynard 883 2000 Classic COSTS 46 Jared Wood Aylesbury - Formula Vauxhall Lotus 2000 Classic Base car from around £5,000 - £40,000, 50 Matthew Bromage Borrowash - Ralt RT30 2000 Classic dependent on class. 57 Edward Guest Bury St. Edmunds - Anson SA4 2000 Classic Full season from around £4,000 - £10,000 64 Marcus Sheard Thurlton AViT! Motorsport Reynard 883 2000 Classic 12 Phil Davis Stroud - Van Diemen RF98 1800 1800 CLASSES Mono 1800 111 Jeff Williams Shepherdswell - Van Diemen RF82 2000 1800 Typical Chassis – FF 1800 Zetec, FF 1600 117 Chris Lord Totnes - Reynard SF86 2000 1800 Duratec, FF2000 161 Julian Hoskins High Wycombe - Vector TF93Z 1800 1800 -

Collecting Practices in Bandjoun, Cameroon Thinking About Collecting As a Research Paradigm

Collecting Practices in Bandjoun, Cameroon Thinking about Collecting as a Research Paradigm Ivan Bargna All photos by author, except where otherwise noted he purpose of my article is to inquire about the parison which is always oriented and located somewhere, in an way that different kinds of image and object individual and collective collection experience, and in a theo- collections can construct social memory and retical and methodological background and goal. Therefore, in articulate and express social and interpersonal spite of all, the museum largely remains our starting point for relationships, dissent, and conflict. I will exam- two main reasons: firstly, because the “museum” is also found ine this topic through research carried out in in Bandjoun; and secondly, because we can use the museum the Bamileke kingdom of Bandjoun, West Cameroon, since stereotype as a conventional prototype for identifying the simi- T2002 (Fig. 1). The issues involved are to some extent analogous larities and differences that compose the always open range of to those concerning the transmission of written texts: continuity possibilities that we call “collection.” To be clear, in considering and discontinuity; translations, rewritings, and transformations; the museum as a stereotypical prototype, I do not ignore the fact political selections and deliberate omissions (Forty and Kuchler that the concept of the museum and its definition change over 1999). Nevertheless, things are not texts, and we must remain time and that every history written in terms of -

Structural and Magnetic Study of the Pan-African Bandja Granitic Pluton (West Cameroon)

Transpressional granite-emplacement model: Structural and magnetic study of the Pan-African Bandja granitic pluton (West Cameroon) A F Yakeu Sandjo1,2,∗, T Njanko1,3, E Njonfang4, E Errami5, P Rochette6 and EFozing1 1Laboratory of Environmental Geology, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 67, Dschang, Cameroon. 2Ministry of Water Resources and Energy, DR/C, Gas and Petroleum Products Service, P.O. Box 8020, Yaound´e, Cameroon. 3Ministry of Scientific Research and Innovation, DPSP/CCAR, P.O. Box 1457, Yaound´e, Cameroon. 4Laboratory of Geology, ENS, The University of Yaound´eI, P.O. Box 47, Yaound´e, Cameroon. 5Department of Geology, Faculty of Sciences, The Choua¨ıbDoukkali University of El Jadida, P.O. Box 20, 24000 El Jadida, Morocco. 6CEREGE UMR7330 Aix-Marseille Universit´e CNRS, 13545 Aix-en-provence, France. ∗Corresponding author. e-mail: [email protected] The Pan-African NE–SW elongated Bandja granitic pluton, located at the western part of the Pan-African belt in Cameroon, is a K-feldspar megacryst granite. It is emplaced in banded gneiss and its NW border underwent mylonitization. The magmatic foliation shows NE–SW and NNE–SSW strike directions with moderate to strong dip respectively in its northern and central parts. This mostly, ferromagnetic granite displays magnetic fabrics carried by magnetite and characterized by (i) magnetic foliation with best poles at 295/34, 283/33 and 35/59 respectively in its northern, central and southern parts and (ii) a subhorizontal magnetic lineation with best line at 37/8, 191/9 and 267/22 respectively in the northern, central and southern parts. Magnetic lineation shows an ‘S’ shape trend that allows to (1) consider the complete emplacement and deformation of the pluton during the Pan-African D2 and D3 events which occurred in the Pan-African belt in Cameroon and (2) reorganize Pan-African ages from Nguiessi Tchakam et al. -

BRSCC Formula Ford 1600 Race Report Season 2015 - Issue 3: Donington Park Grand Prix Circuit, 9/10Th May DONNY DRAMA Dussault: Triumph and Tragedy

BRSCC Formula Ford 1600 Race Report Season 2015 - Issue 3: Donington Park Grand Prix Circuit, 9/10th May DONNY DRAMA Dussault: Triumph and Tragedy Jardine Bounces Back BRSCC Formula Ford 1600: Race Report - Donington Park Grand Prix Circuit, 9/10th May CONTENTS Page Introduction 3 Pre90 Qualifying 4 Post89 Qualifying 6 Faces of FF1600 8 Pre90 Race 1 9 Post89 Race 1 12 Pre90 Race 2 16 Post89 Race 2 19 Data & Credits Meeting Type: Double Header Words: Dave Williams Circuit: Donington Park Grand Prix Editing: Dave Williams Circuit Length: 2.4873 miles www.gramtext.co.uk National Championship: Rounds 3 & 4 Copyright on Pictures: Bourne Northern Championship: Rounds 3 & 4 Photographic Triple Crown: Rounds 1 & 2 www.bournephotographic.co.uk Organised by BRSCC Next Event: Sponsored by Avon Tyres 23rd May: Oulton Park National Championship: Rounds 5 & 6 Northern Championship: Rounds 5 BRSCC FF1600 Championship Co-ordinator: Ian Smith (07939 107888) Page: 2 www.brsccff1600.co.uk BRSCC Formula Ford 1600: Race Report - Donington Park Grand Prix Circuit, 9/10th May Introduction There were points galore on offer when the BRSCC members who race in our Avon Tyres-sponsored Formula Ford 1600 portfolio visited Donington Park on the second weekend of May with results counting towards the National and Northern Championships as well as the Triple Crown. The season can be said to be in full- swing with all 3 of our multi-venue series now under way. What a season it is turning out to be with the Post89 category in particular booming on the National scene. Following on from Friday evening’s exclusive FF1600 test session, which was organised in conjunction with Bookatrack.com, 27 Class A and B cars took to the track to qualify for race 1 on Saturday morning. -

Chapter 6 Third Person Pronouns in Grassfields Bantu Larry M

Chapter 6 Third person pronouns in Grassfields Bantu Larry M. Hyman University of California, Berkeley “In linguistic theory, the 3rd person has had bad luck.” (Pozdniakov n.d.: 5) In this paper I have two goals. First, I propose a reconstruction of the pronoun system of Grassfields Bantu, direct reflexes of which are found in Eastern Grass- fields, with a close look at the pronoun systems, as reflected across thisvaried group. Second, I document and seek the origin of innovative third person pro- nouns in Western Grassfields. While EGB languages have basic pronouns inall persons, both the Momo and Ring subgroups of WGB have innovated new third person (non-subject) pronouns from demonstratives or perhaps the noun ‘body’. However, these languages show evidence of the original third person pronouns which have been restricted to a logophoric function. I end with a comparison of the Grassfields pronouns with nearby Bantoid and Northwest Bantu languages as well as Proto-Bantu. 1 The problem While Eastern Grassfields Bantu, like Narrow Bantu, has an old and consistent paradigm of pronouns, Western Grassfields Bantu has innovated new third per- son forms, often keeping the original forms as logophoric pronouns. The major questions I address in this chapter are: (i) Where do these new third person pro- nouns come from? (ii) Why were they innovated? (iii) What is the relation, if any, Larry M. Hyman. Third person pronouns in Grassfields Bantu. In JohnR. Watters (ed.), East Benue-Congo: Nouns, pronouns, and verbs, 199–221. Berlin: Language Science Press. DOI:10.5281/zenodo.1314329 Larry M. Hyman to logophoricity? In the following sections I first briefly introduce the subgroup- ing of Grassfields Bantu that I will be assuming, then successively treat thirdper- son pronouns in the different subgroups: Eastern Grassfields, Ring Grassfields, and Momo Grassfields. -

Traditions and Bamiléké Cultural Rites: Tourist Stakes and Sustainability

PRESENT ENVIRONMENT AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT, VOL. 7, no. 1, 2013 TRADITIONS AND BAMILÉKÉ CULTURAL RITES: TOURIST STAKES AND SUSTAINABILITY Njombissie Petcheu Igor Casimir1 , Groza Octavian2 Tchindjang Mesmin 3, Bongadzem Carine Sushuu4 Keywords: Bamiléké region, tourist resources, ecotourism, coordinated development Abstract. According to the World Travel Tourism Council, tourism is the first income-generating activity in the world. This activity provides opportunities for export and development in many emerging countries, thus contributing to 5.751 trillion dollars into the global economy. In 2010, tourism contributed up to 9.45% of the world GDP. This trend will continue for the next 10 years and tourism will be the leading source of employment in the world. While many African countries (Morocco, Gabon etc.) are parties to benefit from this growth, Cameroon, despite its huge touristic potential, seems ill-equipped to take advantage of this alternative activity. In Cameroon, tourism is growing slowly and is little known by the local communities which depend on agro-pastoral resources. The Bamiléké of Cameroon is an example faced with this situation. Nowadays in this region located in the western highlands of Cameroon, villages rich in natural, traditional or socio-cultural resources, are less affected by tourist traffic. This is probably due to the fact that tourism in Cameroon is sinking deeper and deeper into a slump, with the degradation of heritages, reception facilities and the lack of planning. In this country known as "Africa in miniature", tourism has remained locked in certain areas (northern part), although the tourist sites of Cameroon are not as limited as one may imagine. -

Appendix 1: Bibliography

Appendix 1: Bibliography Chapter 1 1 Aston, B. and Williams, M., Playing to Win, Institute of Public Policy Research, 1996. 2 Williams, K., Williams, J. and Thomas D., Why are the British Bad at Manufacturing, Routledge & Keegan Paul, 1983. 3 Economist Intelligence Unit, World Model Production Forecasts 1999. 4 SMMT, Motor Industry of Great Britain 1986, World Automotive Statistics, London. 5 Maxton, G. P. and Wormald, J., Driving Over a Cliff?, EIU Series, Addison-Wesley, 1994. 6 Turner, G., The Leyland Papers, Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1971. 7 World Economic Development Review, Kline Publishing/McGraw Hill, 1994. 8 United Kingdom Balance of Payments, Office for National Statistics, 1998. 9 Court, W., A History of Grand Prix Motor Racing 1906–1951, Macdonald, 1966. 10 Crombac, G., Colin Chapman, Patrick Stephens, 1986. 11 Garrett, R., The Motor Racing Story, Stanley Paul & Co Ltd, 1969. 12 Jenkinson, D., and Posthumus, C., Vanwall, Patrick Stephens, 1975. 13 Hamilton, M., Frank Williams, Macmillan, 1998. 14 Mays, R., and Roberts, P., BRM, Cassell & Company, 1962. 15 Rendall, I., The Power and the Glory, BBC Books, 1991. 16 Underwood, J., The Will to Win. John Egan and Jaguar, W.H.Allen & Co. Ltd, 1989. 17 Henry, A., March, The Grand Prix & Indy Cars, Hazleton Publishing, 1989. 263 264 Britain’s Winning Formula Chapter 2 1 Motor Sports Association, The, British Motorsports Yearbooks, Motor Sports Association [MSA], 1997–9. 2 David Hodges, David Burgess-Wise, John Davenport and Anthony Harding, The Guinness Book of Car Facts and Feats, Guinness Publishing, 4th edn, 1994. 3 Ian Morrison, Guinness Motor Racing Records, Facts and Champions, Guinness Publishing, 1989. -

Plants Used in Bandjoun Village (La

The Journal of Phytopharmacology 2016; 5(2): 56-70 Online at: www.phytopharmajournal.com Research Article Plants used in Bandjoun village (La'Djo) to cure infectious ISSN 2230-480X diseases: An ethnopharmacology survey and in-vitro Time- JPHYTO 2016; 5(2): 56-70 March- April Kill Assessment of some of them against Escherichia coli © 2016, All rights reserved S.P. Bouopda Tamo*, S.H. Riwom Essama, F.X. Etoa S.P. Bouopda Tamo ABSTRACT Department of Biochemistry, Laboratory of Microbiology, An ethnopharmacology survey concerning the medicinal plants used in Bandjoun village (La'Djo) to cure University of Yaoundé I, PO Box infectious diseases was carried out in three districts of this village. The survey led to the identification of 79 812 Yaoundé, Cameroon medicinal plants species listed in 41 families. These plants were cited to be use to treat about 25 infectious diseases among which malaria, diarrhea and intestinal-worms were the most cited. Chromolaena odorata, S.H. Riwom Essama Voacanga africana, Moringa oleifera, Mammea africana, Euphorbia hirta, Psidium guajava, Allium cepa, Department of Microbiology, Enantia chlorantha, Alstonia boonei and Picralima nitida, were the ten most cited plants. Extractions of parts Laboratory of Microbiology, of these last plants were performed in hydro-ethanol (3:7) solvent and then tested in-vitro against an University of Yaoundé I, PO Box Escherichia coli isolate. The minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) and minimal bactericidal concentration 812 Yaoundé, Cameroon (MBC) were assessed by microdilution assay and the time-kill assessment was carried out by measure of log reduction in viable cell count, on a period of 48 hours. -

Club Racing Media Guide and Record Book

PLAYGROUND EARTH BEGINS WHERE YOUR DRIVEWAY ENDS. © 2013 Michelin North America, Inc. BFGoodrich® g-ForceTM tires bring track-proven grip to the street. They have crisp steering response, sharp handling and predictable feedback that bring out the fun of every road. They’re your ticket to Playground EarthTM. Find yours at bfgoodrichtires.com. Hawk Performance brake pads are the most popular pads used in the Sports Car Club of America (SSCA) paddock. For more, visit us at www.hawkperformance.com. WHAT’SW STOPPING YOU? Dear SCCA Media Partners, Welcome to what is truly a new era of the Sports Car Club of America, as the SCCA National Champi- onship Runoffs heads west for the first time in 46 years to Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca. This event, made possible with the help of our friends and partners at Mazda and the Sports Car Rac- ing Association of the Monterey Peninsula (SCRAMP), was met with questions at its announcement that have been answered in a big way, with more than 530 drivers on the entry list and a rejunvenaton of the west coast program all season long. While we haven’t been west of the Rockies since River- side International Raceway in 1968, it’s hard to believe it will be that long before we return again. The question on everyone’s mind, even more than usual, is who is going to win? Are there hidden gems on the west coast who may be making their first Runoffs appearance that will make a name for themselves on the national stage, or will the traditional contenders learn a new track quickly enough to hold their titles? My guess is that we’ll see some of each. -

Proceedingsnord of the GENERAL CONFERENCE of LOCAL COUNCILS

REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON REPUBLIQUE DU CAMEROUN Peace - Work - Fatherland Paix - Travail - Patrie ------------------------- ------------------------- MINISTRY OF DECENTRALIZATION MINISTERE DE LA DECENTRALISATION AND LOCAL DEVELOPMENT ET DU DEVELOPPEMENT LOCAL Extrême PROCEEDINGSNord OF THE GENERAL CONFERENCE OF LOCAL COUNCILS Nord Theme: Deepening Decentralization: A New Face for Local Councils in Cameroon Adamaoua Nord-Ouest Yaounde Conference Centre, 6 and 7 February 2019 Sud- Ouest Ouest Centre Littoral Est Sud Published in July 2019 For any information on the General Conference on Local Councils - 2019 edition - or to obtain copies of this publication, please contact: Ministry of Decentralization and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) Website: www.minddevel.gov.cm Facebook: Ministère-de-la-Décentralisation-et-du-Développement-Local Twitter: @minddevelcamer.1 Reviewed by: MINDDEVEL/PRADEC-GIZ These proceedings have been published with the assistance of the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ) through the Deutsche Gesellschaft für internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH in the framework of the Support programme for municipal development (PROMUD). GIZ does not necessarily share the opinions expressed in this publication. The Ministry of Decentralisation and Local Development (MINDDEVEL) is fully responsible for this content. Contents Contents Foreword ..............................................................................................................................................................................5