Gall's Visit to the Netherlands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

Basil Kerski

Akademie der Künste – European Alliance of Academies “They love to talk the talk, but what about walking the walk?” For European commitment against nationalism Basil Kerski Grass-Chodowiecki. Art defends diversity of identities - The feeling of gratitude for the invitation is nurtured by the fact that the trip from Berlin to Gdansk always awakens emotions and associations for me; personal ones (born in Gdansk, Iraqi father, Polish mother, living in Iraq, fled from there via Poland to West Berlin; Berlin, my second home; optimal location due to its Polish connections and new German- Middle Eastern identities; spiritual home of my ancestors; Jewish Dubs family from Lemberg/Lviv, which was shaped by Moses Mendelssohn; also a difficult place due to the experience of German crimes) - But as I travel from Gdansk to the Akademie der Künste in Berlin, I think above all of two Academy directors of the preceding organisations: Daniel Chodowiecki (born in 1726 in Gdansk), copper engraver, painter, Director of the Royal Prussian Academy Berlin from 1797 to 1801, son of a Polish Catholic nobleman and a Swiss Huguenot, successful in Berlin. I think of him, not because I am so familiar with the history of the Academy, no, but rather because Chodowiecki is a symbolic figure for today‘s democratic Gdansk. His graphic cycle dated 1773 about his trip to Gdansk and his two-month stay there is the most important document of a lost urban culture in Gdansk (predominantly Protestant German) in the Polish Republic of Nobles. At the time, Gdansk was the main port of the Polish- Lithuanian Republic of Nobles. -

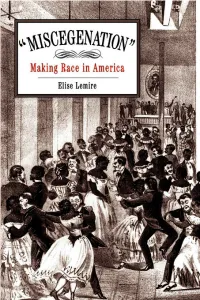

Miscegenation” This Page Intentionally Left Blank “Miscegenation” Making Race in America

“Miscegenation” This page intentionally left blank “Miscegenation” Making Race in America ELISE LEMIRE PENN UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS Philadelphia Copyright © 2002 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lemire, Elise Virginia. “Miscegenation” : making race in America / Elise Lemire. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8122-2064-3 (alk. paper) 1. American literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Miscegenation in literature. 3. Literature and society—United States—History—19th century. 4. Jeff erson, Th omas, 1743–1826—In literature. 5. Racially mixed people in literature. 6. Race relations in literature. 7. Racism in literature. 8. Race in literature. I. Title. PS217.M57 L46 2002 810.9'355—dc21 2002018048 For Jim This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Introduction: The Rhetorical Wedge Between Preference and Prejudice 1 1. Race and the Idea of Preference in the New Republic: The Port Folio Poems About Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings 11 2. The Rhetoric of Blood and Mixture: Cooper’s “Man Without a Cross” 35 3. The Barrier of Good Taste: Avoiding A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation in the Wake of Abolitionism 53 4. Combating Abolitionism with the Species Argument: Race and Economic Anxieties in Poe’s Philadelphia 87 5. Making “Miscegenation”: Alcott’s Paul Frere and the Limits of Brotherhood After Emancipation 115 Epilogue: “Miscegenation” Today 145 Notes 149 Bibliography 179 Index 191 Acknowledgments 203 This page intentionally left blank Illustrations 1. -

Faculties and Phrenology

Reflection University Press Scholarship Online Oxford Scholarship Online The Faculties: A History Dominik Perler Print publication date: 2015 Print ISBN-13: 9780199935253 Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: May 2015 DOI: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199935253.001.0001 Reflection Faculties and Phrenology Rebekka Hufendiek Markus Wild DOI:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199935253.003.0009 Abstract and Keywords This Reflection considers how the science of phrenology relates to the notion of faculty. It asks: why is phrenology so appealing? It illustrates this with reference to modern culture. Firstly, the Reflection argues, phrenology relies on an easy line of reasoning: moral and mental faculties are found in specific areas of the brain. The more persistently such faculties prevail, the bigger the respective part of the brain. Secondly, phrenology produces easy visible evidence. You can read the mental makeup of someone by looking and feeling the lumps in their head. The Reflection goes on to look at the history of phrenology and relate it to issues of race. Keywords: phrenology, brain, race, head, history of phrenology Page 1 of 8 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2018. All Rights Reserved. Under the terms of the licence agreement, an individual user may print out a PDF of a single chapter of a monograph in OSO for personal use (for details see http://www.oxfordscholarship.com/page/privacy-policy). Subscriber: Universitat Basel; date: 20 June 2018 Reflection In Quentin Tarantino’s western Django Unchained (2012), the southern slave owner Calvin Candie, played by Leonardo DiCaprio, explains to his guests the unwillingness of slaves to rise up and take revenge by putting the skull of a recently deceased slave on the dinner table. -

Using Facial Angle to Prove Evolution and the Human Race Hierarchy Jerry Bergman

Papers Using facial angle to prove evolution and the human race hierarchy Jerry Bergman A measurement technique called facial angle has a history of being used to rank the position of animals and humans on the evolutionary hierarchy. The technique was exploited for several decades in order to prove evolution and justify racism. Extensive research on the correlation of brain shapes with mental traits and also the falsification of the whole field of phrenology, an area to which the facial angle theory was strongly linked, caused the theory’s demise. he use of the facial angle, a method of measuring but also the difference between the human “races”.8 Science Tthe forehead-to-jaw relationship, has a long history historian John Haller concluded that the “facial angle was and was often used to make judgments of inferiority and the most extensively elaborated and artlessly abused criteria superiority of certain human races. University of Chicago for racial somatology.”2 zoology professor Ransom Dexter wrote that the “subject of Supporters of this theory cited as proof convincing, the facial angle has occupied the attention of philosophers but very distorted, drawings of an obvious black African or from earliest antiquity.”1 Aristotle used it to help determine Australian Aborigine as being the lowest type of human and a person’s intelligence and to rank humans from inferior a Caucasian as the highest racial type. The slanting African to superior.2 It was first used in modern times to compare forehead shown in the pictures indicates a smaller frontal human races by Petrus Camper (1722–1789), and it became cortex, such as is typical of an ape, demonstrating to naïve widely popular until disproved in the early 20th century.2 observers their inferiority. -

Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the Fashioning of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Fall 1-7-2020 Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the Fashioning of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities Jeffrey Braytenbah Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, and the Asian Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Braytenbah, Jeffrey, "Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the ashioningF of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities" (2020). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5356. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7229 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Crania Japonica: Ethnographic Portraiture, Scientific Discourse, and the Fashioning of Ainu/Japanese Colonial Identities by Jeff Braytenbah A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Kenneth J. Ruoff, Chair Laura Robson Jennifer Tappan Portland State University 2019 © 2019 Jeff Braytenbah Abstract Japan’s colonial activities on the island of Hokkaido were instrumental to the creation of modern Japanese national identity. Within this construction, the indigenous Ainu people came to be seen in dialectical opposition to the 'modern' and 'civilized' identity that Japanese colonial actors fashioned for themselves. This process was articulated through travel literature, ethnographic portraiture, and discourse in scientific racism which racialized perceived divisions between the Ainu and Japanese and contributed to the unmaking of the Ainu homeland: Ainu Mosir. -

Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(S): Londa Schiebinger Source: the American Historical Review, Vol

Why Mammals are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History Author(s): Londa Schiebinger Source: The American Historical Review, Vol. 98, No. 2 (Apr., 1993), pp. 382-411 Published by: American Historical Association Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2166840 Accessed: 22/01/2010 10:27 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aha. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. American Historical Association is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The American Historical Review. http://www.jstor.org Why Mammals Are Called Mammals: Gender Politics in Eighteenth-Century Natural History LONDA SCHIEBINGER IN 1758, IN THE TENTH EDITION OF HIS Systema naturae, Carolus Linnaeus introduced the term Mammaliainto zoological taxonomy. -

196179395.Pdf

University of Groningen Intergenerational transmission of occupational status before modernization Marchand, Wouter IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Other version Publication date: 2016 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Marchand, W. (2016). Intergenerational transmission of occupational status before modernization: the case of reformed preachers in Friesland, 1700-1800. 1-21. Paper presented at 11th European Social Science and History Conference, Valencia, Spain. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 29-04-2019 Wouter Marchand & Jacobus Teitsma Joha Intergenerational transmission of occupational status before modernization: the case of reformed preachers in Friesland, 1700-1800. THIS IS A DRAFT VERSION – DO NOT CITE European Social Science History Conference, Valencia April 2, 2016 Corresponding author: Dr. Wouter Marchand Junior Assistant Professor Dept. of History and Art History Research group Economic and Social History Utrecht University [email protected] Marchand & Joha ESSHC 2016 1. -

COGNITIVE SCIENCE 107A History of Cognitive Neuroscience

COGNITIVE SCIENCE 107A History of Cognitive Neuroscience Jaime A. Pineda, Ph.D. The Fundamental Circularity of Being “The world is inseparable from the subject, but from a subject which is nothing but a projection of the world, and the subject is inseparable from the world, but from a world which the subject itself projects.” Merleau-Ponty (1906-1961) BODY-MIND RELATIONSHIP (STRUCTURE-FUNCTION) • BODY/BRAIN • MIND Memory Attention Language Planning Creativity Awareness Consciousness Classical physics BODY-MIND RELATIONSHIP (STRUCTURE-FUNCTION) • BODY/BRAIN • MIND Memory Attention Language Planning Creativity Awareness Consciousness Self-directed neural plasticity? Quantum physics and the causal efficacy of thought? CLAUDIUS GALEN (ca. 131-201) • Expanded Aristotle’s ideas of Humors The body is composed of a balance between the four elements present on earth- fire, earth, water, and air- which were manifested in the body as yellow bile (choler), black bile (melancholy), blood, and phlegm. Galen’s “psychic pneuma”: “vital spirits” formed in the heart and were pumped to the brain, where they mixed with “pneuma” (air found in the cavities of the brain). This model held sway for 1500 years Andreas Vesalius (1514-1564) De Humani Corporis Fabrica (The Fabric of The Human Body) – 1543 Studied anatomy solely for structure Did not get some of the convolutions of the brain right; argued that Galen was wrong; was branded a heretic and fled. Rene Descartes (1596-1650) De Homine – 1662 Mechanistic view of brain Pineal gland – gateway to soul “…ingenuity and originality were unfortunately based on pure speculation and incorrect anatomical observations.” “I think therefore I am” Luigi Galvani (1737-1798) Professor of Obstetrics Moves frog leg with static electricity Detects electricity in the nerves of frogs Bell –Magendi Law 1811 Doctrine of Specific Nerve Energies Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828) Analysis of the shapes and lumps of the skull would reveal a person’s personality and intellect. -

4. Rudolf MAURER, Dr. Gall´S Schädelsammlung, 92 Seiten

Katalogblätter des Rollettmuseums Baden, Nr. 4 Rudolf Maurer Dr. Gall’s Schädelsammlung Baden 2008 ISBN 978-3-901951-04-6 F.d.I.v.: Städt. Sammlungen Baden – Archiv / Rollettmuseum 2500 Baden, Weikersdorferplatz 1 / Elisabethstr. 61 02252/48255 [email protected] Druck: Abele, Baden Franz Josef Gall (1758 – 1828) Hier ist nicht der Ort, eine neue Biographie Galls vorzulegen. Es sollen nur die wichtigsten Daten als Hintergrund für das Entstehen der Schädelsammlung und ihre Übertragung in das Rollettmuseum Baden zusammengefasst werden. Am 9. März 1758 in Tiefenbronn bei Pforzheim geboren, studierte Franz Josef Gall seit 1777 in Straßburg Medizin. 1781 übersiedelte er nach Wien, wo er seine Stu- dien 1785 erfolgreich abschloss. 1790 heiratete er Maria Katharina Leisler. Durch die schnellen Erfolge seiner Arztpraxis konnten sich die beiden in der Ungargasse im Wiener III. Bezirk ein Haus leisten, dessen Garten Gall selbst mit Leidenschaft betreute. Tiefenbronn bei Pforzheim, Ortskern und Geburtshaus Galls (Fotos Wolfgang Schütz, 2007) Gall sah sich aber auch als Wissenschaftler und spezialisierte sich auf die Erfor- schung des menschlichen Gehirns. Fast intuitiv schwebte ihm die Herstellung eines Zusammenhangs der Schädelform mit den darunter gelegenen Gehirnorganen vor. 1796 war sein System, das man später Schädellehre, Phrenologie oder Kraniosko- pie nannte, so weit ausgereift, dass er begann, Privatvorlesungen darüber zu halten. Auch durch den Vergleich mit Tiergehirnen versuchte Gall Erkenntnisse über das menschliche Gehirn zu gewinnen, was ihn geradezu zur Verhaltensforschung im heutigen Sinn führte. Leider wissen wir nicht, ob die folgende Anekdote in Wien oder in Paris gedacht ist: „Nachdem ich Gall meine Empfehlungsschreiben überreicht hatte,“ erzählt ein Engländer, „führte er mich in ein Zimmer, dessen Wände mit Vogelbauern, dessen Boden mit Hunden, Ratten usw. -

The Birth of Scientific Publishing — Descartes in the Netherlands

A Century of Science Publishing E.H. Fredriksson (Ed.) IOS Press, Chapter The Birth of Scientific Publishing — Descartes in the Netherlands Jean Galard Cultural Department, Musée du Louvre, Paris, France René Descartes (–) occupies an eminent place at a crucial moment in the history of thought. He played a decisive role when the medieval scholastic tra- dition was supplanted by the modern scientific mind. His personal contribution to the attainments of science was perhaps modest (most of his theories were soon out- dated). But he incarnated a new attitude of the mind towards the world; he for- mulated a new method; he furnished the essential bases for the future development of knowledge. His books, which were all written in the Netherlands, are examples of the spectacular birth of scientific publications. However, by a noteworthy paradox, they were directed against the cult of the Book. Descartes, like Galileo, relied on observation, on direct experience, aided by reasoning, at a time when intellectual authority was incarnated by the canonical books, those of Aristotle. The Cartesian moment in the history of thought is marked by a refusal of opinions conveyed by ancient books. It was the moment of the true re-foundation of thought, indepen- dent of bookish culture. An anecdote illustrates it well. A gentleman went to visit Descartes at Egmond, in Holland, where the philosopher resided from , and asked him for the books of physics that he used. Descartes declared that he would willingly show them to him: he took his visitor in a courtyard, behind his dwelling, and showed the body of a calf that he was about to dissect. -

UC GAIA Wagner CS5.5-Text.Indd

Pathological Bodies The Berkeley SerieS in BriTiSh STudieS Mark Bevir and James Vernon, University of California, Berkeley, editors 1. The Peculiarities of Liberal Modernity in Imperial Britain, edited by Simon Gunn and James Vernon 2. Dilemmas of Decline: British Intellectuals and World Politics, 1945– 1975, by Ian Hall 3. The Savage Visit: New World People and Popular Imperial Culture in Britain, 1710– 1795, by Kate Fullagar 4. The Afterlife of Empire, by Jordanna Bailkin 5. Smyrna’s Ashes: Humanitarianism, Genocide, and the Birth of the Middle East, by Michelle Tusan 6. Pathological Bodies: Medicine and Political Culture, by Corinna Wagner Pathological Bodies Medicine and Political Culture Corinna Wagner Global, Area, and International Archive University of California Press Berkeley loS angeleS london The Global, Area, and International Archive (GAIA) is an initiative of the Institute of International Studies, University of California, Berkeley, in partnership with the University of California Press, the California Digital Library, and international research programs across the University of California system. University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 2013 by The Regents of the University of California Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress iSBn: 978-1938169-08-3 Manufactured in the United States of America 22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of anSi/niSo z39.48– 1992 (r 1997) (Permanence of Paper).