Response to Wiltshire Core Strategy Focused Consultation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Impact of Wind Turbine Noise on Health

Wind Turbines and Proximity to Homes: The Impact of Wind Turbine Noise on Health a review of the literature & discussion of the issues by Barbara J Frey, BA, MA (University of Minnesota) & Peter J Hadden, BSc (Est Man), FRICS January 2012 Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity. -- The World Health Organization Charter The objective of science is not agreement on a course of action, but the pursuit of truth. -- John Kay (2007) First, Do No Harm. -- The Hippocratic Oath Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Preface 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1 Wind Turbines built near Homes: the Effects on People 8 Appendix 1: People’s Health Experiences: Additional References 21 Chapter 2 Wind Turbine Noise and Guidance 22 2.1 Wind turbine noise 22 2.2 Wind turbine noise guidance 38 2.3 Wind turbine noise: Guidance process 43 2.4 Wind turbine noise: Low frequency noise (LFN) 54 2.5 Wind turbine noise: Amplitude modulation (AM) 60 Appendix 2: Wind Turbine Noise & Guidance: Additional References 65 Chapter 3 Wind Turbine Noise: Impacts on Health 67 3.1 Wind turbine noise and its impacts on health, sleep, and cognition 67 3.2 Wind turbine noise: Clinical studies and counterclaims 92 Appendix 3.1 Health: International Perspectives 101 Appendix 3.2 Health: Additional References 102 Chapter 4 Wind Turbine Noise and Human Rights 103 4.1 Potential violations 103 4.2 The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights 112 4.3 State Indifference to Human Rights: -

Wind Turbines and Proximity to Homes

! ! ! ! ! ! ! Wind Turbines and Proximity! to Homes: The Impact of Wind Turbine Noise on Health a review of the literature & discussion of the issues ! ! ! by! ! Barbara J Frey, BA, MA (University of Minnesota) & Peter J Hadden, BSc (Est Man), FRICS January 2012 Health is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being, and not merely the absence of disease and infirmity. -- The World Health Organization Charter The objective of science is not agreement on a course of action, but the pursuit of truth. -- John Kay (2007) First, Do No Harm. -- The Hippocratic Oath ! "! Table of Contents ! Acknowledgements 3 Preface 4 Introduction 5 Chapter 1 Wind Turbines built near Homes: the Effects on People 8 Appendix 1: People’s Health Experiences: Additional References 21 Chapter 2 Wind Turbine Noise and Guidance 22 2.1 Wind turbine noise 22 2.2 Wind turbine noise guidance 38 2.3 Wind turbine noise: Guidance process 43 2.4 Wind turbine noise: Low frequency noise (LFN) 54 2.5 Wind turbine noise: Amplitude modulation (AM) 60 Appendix 2: Wind Turbine Noise & Guidance: Additional References 65 Chapter 3 Wind Turbine Noise: Impacts on Health 67 3.1 Wind turbine noise and its impacts on health, sleep, and cognition 67 3.2 Wind turbine noise: Clinical studies and counterclaims 92 Appendix 3.1 Health: International Perspectives 101 Appendix 3.2 Health: Additional References 102 Chapter 4 Wind Turbine Noise and Human Rights 103 4.1 Potential violations 103 4.2 The United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights 112 4.3 State Indifference to -

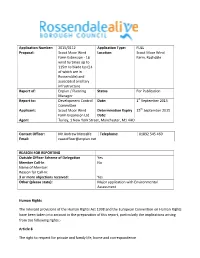

2015/0112 Application Type: FULL Proposal: Scout Moor Wind Farm

Application Number: 2015/0112 Application Type: FULL Proposal: Scout Moor Wind Location: Scout Moor Wind Farm Extension - 16 Farm, Rochdale wind turbines up to 115m to blade tip (14 of which are in Rossendale) and associated ancillary infrastructure Report of: Enplan / Planning Status For Publication Manager Report to: Development Control Date: 1st September 2015 Committee Applicant: Scout Moor Wind Determination Expiry 15th September 2015 Farm Expansion Ltd Date: Agent Turley, 1 New York Street, Manchester, M1 4HD Contact Officer: Mr Andrew Metcalfe Telephone: 01892 545 460 Email: [email protected] REASON FOR REPORTING Outside Officer Scheme of Delegation Yes Member Call-In No Name of Member: Reason for Call-In: 3 or more objections received: Yes Other (please state): Major application with Environmental Assessment Human Rights The relevant provisions of the Human Rights Act 1998 and the European Convention on Human Rights have been taken into account in the preparation of this report, particularly the implications arising from the following rights:- Article 8 The right to respect for private and family life, home and correspondence. Article 1 of Protocol 1 The right of peaceful enjoyment of possessions and protection of property. Report Structure 1. THE SITE ..........................................................................................................................................................3 2. SITE PLANNING HISTORY ................................................................................................................................4 -

INWG AM Study Wp3a

Wind Turbine Amplitude Modulation and Planning Control Study Work Package 3.1 - Study of Noise and Amplitude Modulation Complaints Received by Local Planning Authorities in England Author: Trevor Sherman Trevor Sherman is an international management consultant currently specialising in senior executive coaching and leadership development training. He has extensive experience of data gathering, analysis, assessment and reporting. Reviewers: John Yelland MA DPhil (Oxon) MInstP FIET MIOA David J Unwin BSc M.Phil FRGS Emeritus Professor in Geography, Birkbeck, University of London Richard Cowen LLB ©2015 Trevor Sherman & Chris Heaton-Harris. No part of this Study may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise except through the prior written permission of the authors. Limit of liability: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this Study, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of its contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. Page 1 of 40 10 February 2015 Work Package 3.1 – Study of Noise & AM Complaints received by LPAs in England CONTENTS 1 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 3 2 Foreword...................................................................................................................................... -

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 the 52Nd ANNUAL

ANNUAL REPORT 2016 The 52nd ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING OF CPRE DEVON BRANCH WILL BE HELD ON MONDAY 31st July 2017 at 2.30pm at Hatherleigh Community Centre, Bowling Green Lane, Hatherleigh EX20 3HB AGENDA 1. To receive apologies for absence 2. To confirm and sign the Minutes of the previous meeting held on 9th August 2016 3. To receive and approve the Annual Report 4. To receive the Annual Accounts for the year ending 31st December 2016 5. To appoint the Independent Examiner 6. Election of Officers (President and Vice President) Trustees/Executive Committee 7. Resolutions i) To approve the Trustees’ proposal to: a. Establish a Charitable Incorporated Organisation to be called “The Devon Branch of the Campaign to Protect Rural England (the “CIO”) having a constitution, including objects in substance in the form of the draft signed by the Chair, available for viewing on the website of the Branch and laid before the meeting, but subject to such amendments as may be required by the Charity Commission [and/or agreed between the Trustees and the Trustee Board of the Campaign to Protect Rural England (registered charity number 1089685).] b. apply to the Charity Commission to register the CIO as a registered charity, and ii) To authorise the Trustees to make such arrangements as may be appropriate for the transfer of assets and liabilities and the continuity of governance from the Branch to the CIO, to effect an orderly transition to CIO status iii) Thereafter to retain the Branch on the Register of Charities (with its constitution amended in the terms available for viewing on the website of the Branch or in a hard copy upon request by members and to be laid before the meeting) solely for the purpose of ensuring that any legacies bequeathed to the Branch do not fail and instead can be transferred to the CIO. -

PRESENTATION on WIND TURBINE AM by Geoffrey Weller I Am a Chartered Engineer and a Fellow of the Institution of Engineering and Technology

PRESENTATION ON WIND TURBINE AM by Geoffrey Weller I am a Chartered Engineer and a Fellow of the Institution of Engineering and Technology. Much of my career was devoted to developing electronic protection schemes for electrical power systems. This included analysis of noisy electrical signals using digital signal processing, for instance with fast Fourier transforms. I have experience of amplitude modulation of radio-frequency signals. Introduction My evidence shows that ETSU-R-97 is failing to protect windfarm neighbours from Amplitude Modulation, the most distressing characteristic of wind turbine noise. ETSU-R-97 is used throughout the UK to assess wind farm noise in planning applications. As it has been embedded into government policy, it is probably futile to insist that ETSU is wrong. However, I do assert that additional protection for AM is needed for windfarm neighbours where the AM exceeds the maximum level quoted in ETSU. This presentation will summarise some of my Proof of Evidence, mention some events that occurred since I submitted it, and amplify the conclusions I drew previously. What is AM? To demonstrate the character of AM, I would like to play two audio files located at the following web URLs i) https://dl.dropbox.com/u/51620331/Swish_to_Thump.mp3 Source: Dick Bowdler FIOA Noise Consultant http://www.dickbowdler.co.uk/content/publications/ ii) https://dl.dropbox.com/u/51620331/file0895_hi_lo_17dbeq_16b.mp3 Source: Recordings of Nature website. There are actually two separate recordings in this file. Proof of Evidence An important source of evidence is the DTI-commissioned 2006 Hayes McKenzie Partnership report The Measurement of Low Frequency Noise at Three UK Wind Farms which noted that Aerodynamic Modulation was occurring in ways not anticipated by ETSU-R-97 (ETSU). -

Harnessing the Power of the Wind at Den Brook

September 2005 WHO ARE WE? DID YOU KNOW…? HarnessingHarnessing thethe powerpower We have been at the forefront of the wind industry from the very beginning, over two Wind power reduces UK wind resources are decades ago. Renewable Energy Systems (RES) is greenhouse gas emissions by more than enough to meet displacing power generation part of the Sir Robert McAlpine group - a British current renewable energy family-owned firm with over 100 years in the from fossil fuels of the wind at Den Brook targets - 20% of UK electricity of the wind at Den Brook engineering and construction industry. by 2020 To date, we are proud to have completed nearly Noise levels from wind I am writing to update you on the progress of our 1,000 megawatts of wind power capacity farms are on a par with rural proposal for a wind farm near North Tawton, Devon. throughout Britain, Europe, the United States background noise at We are pleased to announce that we shall soon be submitting the planning application to and the Caribbean. night time Early consultation West Devon Borough Council. Accompanying the application is a comprehensive Environmental RES is also proud to be a significant player in with nature conservation Statement. This includes information on how we selected the site, the details of the project and the the blossoming offshore wind industry. Both organisations is essential to help thorough environmental surveys we have undertaken, which identify and predict potential environmental effects onshore and offshore generation are needed if The intermittency of wind developers and planners ensure from the wind farm and outline measures that can be taken to enhance the environment at Den Brook and the we as a nation are to meet our goal of power does not cause any appropriate siting, design and surrounding area. -

European Wind Farms

Gartefjellet (40MW,20) KJØLLEFJORD VIND AS Havøygavlen (40MW,16) Arctic Wind (StatoilHydro) Kjollefjord (39.1MW,17) Kjøllefjord Vind AS (Statkraft) Sandhaugen (1.5MW,1) Norsk Miljøkraft FoU AS Kvalnes, Andøya (0.4MW,1) Andøya Energi AS Hovden, Vesterålen (0.4MW,1) Vesterålskraft Produksjon AS Enontekiö (1.5MW,3) Tunturituuli Oy Nygårdsfjellet I (6.9MW,3) Nordkraft Vind AS Hammarøya vindmølle (0.3MW,1) Nordmøre Energiverk AS Olos 3 (1.8MW,3) Tunturituuli Oy Viscaria (5.4MW,6) Biegg-al mai/Suorva (0.6MW,1) Aapua (10.5MW,7) Hornberg (10MW,5) Bolungarvik Uljabuouda (30MW,10) Skellefteå Kraft Blaiken (300MW,100) Skellefteå Kraft Kemi 1 (0.9MW,3) Kemin Tuulivoimapuisto Oy Storön (0.85MW,1) Kemi (30MW,10) PVO Innopower Oy Kemi (3MW,1) Haminan Energia Oy Ajos (Kemi) 1+2 (24MW,8) Pohjolan Voima Ajos T5 (30MW,10) PVO Innopower Oy Jokkmokksliden (25MW,10) Skellefteå Kraft Kuivaniemi (7MW,8) VAPOn tuulivoima Oy Vatunki 6 (2MW,1) VAPOn tuulivoima Oy Kuivamatala 1 (2.25MW,3) VAPOn tuulivoima Oy Laitakari (0.5MW,3) Iin Energia Oy Ii (1.5MW,2) Iin Energia Oy Ii Laitakari (1MW,1) Dragaliden (24MW,12) Svevind Bondön (35MW,14) Global Green Energy Huikku (0.5MW,1) Hornberget (10MW,5) Jämtkraft AB Vattenfall sähköntuotanto Oy Klimpfjäll (2.7MW,3) Vattenfall AB Hailuoto (1.6MW,4) Spawer Kraft Ab Oulu (4MW,2) PVO Innopower Oy Marjaniemi 3 (0.5MW,1) Riutunkari T4 (3MW,3) Vihreäsaari T2 (3MW,1) Vattenfall sähköntuotanto Oy PVO Innopower Oy PVO Innopower Oy Oulunsalo (10.3MW,6) PVO Innopower Oy Lumijoki (0.66MW,1) Lumituuli Oy Routunkari (0.66MW,1) Lumituuli Oy -

Two Decades of Deception

INWG Work Package 10 – AM Study Summary Wind Turbine Amplitude Modulation & Planning Control Study Work Package 10 - Study Summary Two Decades of Deception Compiled by: Richard Cox Contributing authors: Richard Cowen, Richard Cox, Bev Gray, Chris Hanning, Mike Hulme, Sarah Large, Trevor Sherman, John Yelland © 2015 Richard Cox & Chris Heaton-Harris. No part of this Study may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise except through the prior written permission of the authors. Limit of liability: While the authors have used their best efforts in preparing this Study, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of its contents and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. Page 1 of 49 27 November 2015 INWG Work Package 10 – AM Study Summary Political Sponsor: Chris Heaton-Harris MP Study available at: http://www.heatonharris.com/reports-publications Community Sponsor: National Alliance of Wind Farm Action Groups Study Objective: To protect communities and wind turbine neighbours from wind turbine noise amplitude modulation INWG contact: [email protected] Work Work Package Subject Lead Author Package 1 Fundamentals of AM John Yelland 2.1 Literature review Richard Cox 2.2 AM Evidence review Sarah Large 3.1 LPA Survey Trevor Sherman 3.2 Health effects Chris Hanning 4 Den Brook Mike Hulme 5 Towards a draft AM condition Sarah Large 6.1 Legal remedies Richard Cowen 6.1A Legal remedies - Supplement Richard Cowen 6.2 Community experience of SN Bev Gray 7 Test of the IoA AMWG methodologies Sarah Large 8 Review of IoA AM study and methodology Richard Cox 9 The Cotton Farm monitor experience Bev Gray 10 Study summary Richard Cox Table 1: INWG AM Study Work Package Division of Work Page 2 of 49 27 November 2015 INWG Work Package 10 – AM Study Summary Contents 1. -

PDF of Wind Farms

Wind Speeds at United Kingdom Wind Farms with known locations Data collected from thewindpower.net and UL's Windnavigator and compiled by Wind Harvest Classification: Public Update: 19 June 2020 Contact: Kevin Wolf, [email protected] 1. Wind speeds will vary across wind farms. This initial estimate used Note only one lat-long per wind farm. 2. This table has an unknown accuracy level. 3. Winds at 20m agl will on average be 0.3 m/s faster than at 15m agl. Total Projected Total Wind Total known % of MW over 6.5 Farms MW over >6.5m/s by Total Wind Farms in m/s at 15m analyzed 6.5m/s at total at 15m Country (MWs) agl (MW) 15m agl agl 13,751 4,478 8,289 2,699 32.6% Wind Farm Name Power (kW) # of Turbines Wind at 80m Wind at 15m agl m/s agl m/s Fair Isle 180 3 8.91 Spurness - Repower 10,000 5 10.28 8.75 Spurness Wind Farm 8,250 3 10.28 8.75 Bu Farm 2,700 3 10.47 8.62 Cemmaes 15,300 18 9.02 8.53 Pentland Road (incorporating13,800 Beinn Mholach)6 10.44 8.34 Slieve Kirk 27,600 12 10.12 8.24 Black Hill 28,600 22 9.89 8.22 Burgar Hill 5,000 2 10.32 8.15 Srondoire Community Windfarm6,000 3 9.59 8.14 Barns of Ayre 2,700 3 9.96 8.12 Ben Aketil 23,000 10 10.03 8.11 Curryfree 15,000 6 9.87 8.07 Novar 17,000 34 9.67 8.01 Hare Hill Extension 29,750 35 9.72 7.85 Kelburn (Green Hill) 28,000 14 9.71 7.81 Ardrossan 24,000 12 9.46 7.81 Ardrossan Extension 6,000 3 9.46 7.81 Carrickatane 20,700 9 9.39 7.8 Beinneun 85,000 25 8.66 7.8 Loch Sminig 2,700 3 9.96 7.78 Millennium (Glenmoriston)40,000 16 9.16 7.76 Millennium (Glenmoriston)15,000 Extension 2 6 8.17 -

Low Carbon Economy Final Report V9

The Low Carbon Economy in the context of the Devon Economy D Lash, M Finus, A.D.S Norton and J Colmer Scientist’s Report 129 September 2010 Centre for Energy and the Environment Physics Building Stocker Road Exeter EX4 4QL UK Tel. (01392) 724143 Fax. (01392) 724111 Website: http://www.ex.ac.uk/cee/ E-mail: [email protected] University of Exeter Business School Department of Economics Streatham Court Rennes Drive Exeter, EX4 4PU UK Tel. (01392) 722574 Website: http://business-school.exeter.ac.uk/ E-mail: [email protected] 1 1 Management Summary 1.1.1 This report forms part of the evidence base for Devon County Council’s (DCC) Local Economic Assessment (LEA). It analyses current emissions of greenhouse gases (GHG) within Devon’s economy and projects the changes in emissions as a result of Government policy. It discusses the threats and weaknesses associated with a move towards a Low Carbon Economy (LCE). 1.1.2 The non-domestic sector is responsible for the majority of emissions in Devon (44%). Within the non-domestic sector agriculture is the largest emitter, mainly due to the high environmental impact of methane, for example from livestock, and nitrous oxide, for example from fertilisers. The manufacturing and the services sectors each have nearly as high an impact as agriculture. Transport is responsible for almost a third of Devon’s emissions, and of these, around three quarters can be allocated to the industry and services sectors. 1.1.3 Transport emissions are over 25% greater proportionally within Devon when compared to the UK average, and agricultural emissions are proportionally double the UK average. -

With an Enlarged Glossary of Cornish Provincial Words

Q)ijouA. aO?. GLOSSARY CORNISH DIALECT, &c. THE AKCIEKT LANGUAGE, AND THE DIALECT OF CORNWALL, WITH AN EXLAKGED GLOSSARY OF CORNISH PROVINCIAL WORDS. ALSO AN APPENDIX, CONTAINING A LIST OF WRITERS ON CORNISH DIALECT, AND ADDITIONAL INFORMATION ABOUT DOLLY PENTREATH, THE LAST KNOWN PERSON WHO SPOKE THE ANCIENT CORNISH AS HER MOTHER TONGUE. BY FRED. W. P. JAGO, M.B. Lond. TEURO : NETHERTON & WORTH, LEMON STREET, 1882. DEDICATION. Loving his native County, its words, and its ways, the writer, with great respect, dedicates this little book to CONTENTS. 1. Frontispiece—Portrait of Dolly Pentreatli, and sketch of her Cottage at Mousehole. 2. The Decline of the Ancient Cornish Language - - 1 3. The Eemains of the Ancient Cornish Language • 17 4. The Preface to WiUiams's Cornish Dictionary - - 29 5. Specimens of the Ancient Cornish Language - - 34 6. The Provincial Dialect of Cornwall .... 45 7. Specimens of the Cornish Provincial Dialect - - 65 8. Words in the Cornish Dialect compared with those found in the writings of Chaucer 73 9. Common English words in the Cornish Dialect, with Tables of them 94 10. On the Glossary of Cornish Provincial "W ords - - 101 11. The Glossary of Cornish Provincial Words - - 102 12. Addenda to Glossary 317 13. Curious Spelling of the Names of Drugs, li'c. - - 325 14. Explanation of the Eeferences in the Glossary - - 827 15. Appendix—DoWy Pentreath . - - - 330 16. Names of Writers on Cornish Dialect, &c. - - 842 PREFACE. Long-descended from Cornishmen, the writer, like others of his countrymen, has a clannish fondness for Cornish words and phrases. From May 1879 to October 1880, the compiler of this book wrote lists of Cornish Provincial Words, which, through the courtesy of the Editor of the " Cornishman," (published at Penzance), were then allowed to appear in that paper.