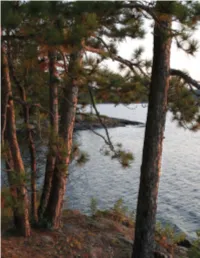

Mallard Island, As Seen from Crow Island

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wilderness, Recreation, and Motors in the Boundary Waters, 1945-1964

Sound Po lit ics SouWildernessn, RecdreatioPn, ano d Mlotoris itn theics Boundary Waters, 1945–1964 Mark Harvey During the midtwentieth century, wilderness Benton MacKaye, executive director Olaus Murie and his preservationists looked with growing concern at the wife Margaret, executive secretary and Living Wilderness boundary waters of northeast Minnesota and northwest editor Howard Zahniser, University of Wisconsin ecolo - Ontario. Led by the Friends of the Wilderness in Minne - gist Aldo Leopold, and Forest Service hydrologist Ber- sota and the Wilderness Society in the nation’s capital, nard Frank. 1 preservationists identified the boundary waters as a pre - MacKaye’s invitation to the council had identified the mier wilderness and sought to enhance protection of its boundary waters in richly symbolic terms: magnificent wild lands and waterways. Minnesota’s con - servation leaders, Ernest C. Oberholtzer and Sigurd F. Here is the place of places to emulate, in reverse, the Olson among them, played key roles in this effort along pioneering spirit of Joliet and Marquette. They came to with Senator Hubert H. Humphrey. Their work laid the quell the wilderness for the sake of civilization. We come foundation for the federal Wilderness Act of 1964, but it to restore the wilderness for the sake of civilization. also revived the protracted struggles about motorized re c - Here is the central strategic point from which to reation in the boundary waters, revealing a deep and per - relaunch our gentle campaign to put back the wilderness sistent fault line among Minnesota’s outdoor enthusiasts. on the map of North America. 2 The boundary waters had been at the center of numer - ous disputes since the 1920s but did not emerge into the Putting wilderness back on the continent’s map national spotlight of wilderness protection until World promised to be a daunting task, particularly when the War II ended. -

Ed Zahniser Talk on Wilderness

"There is [still] just one hope . ." Memory as Inspiration in Advocating Wilderness and Wildness By Ed Zahniser A Brown-bag Lunch Talk by Ed Zahniser to the Staff of the Wilderness Society 900 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006 February 15, 2000 Time as an arrow has not been invented here yet. Time is not an arrow here. Time is not an arrow hurtling along an inevitable trajectory with the neo-Darwinian myth of social progress as its arrowhead. No. Time is like a spiral. And yes, the tradition you and I are so much a part of in this room has been here on Turtle Island since the beginning of time. See, the beginning of time is right down there - see it? It's not far down- right there! On the spiral. We'll be there shortly. Think of spiral time like this Slinky toy. Pass it around. Get a feel for spiral time. That funky gap in this slinky, where the spiral got sprung, well, maybe that's the atomic bomb, Hiroshima, Nagasaki. "We can't talk about atoms anymore because atom means indivisible and we have split it." [Jeanette Winterson] We can talk about wilderness and wildness, about perpetuity. You can hear the beginning of time in our stories we tell. Listen. The alphabet is not invented yet. Our words are still like things. Our words still point to real things in the world of sense and feelings. We still enjoy reciprocity with the sensuous world [David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous]. Trust me. -

Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Papers of Ernest Oberholtzer

GUIDE TO THE MICROFILM EDITION of the PAPERS OF ERNEST OBERHOLTZER Gregory Kinney _~ Minnesota Historical Society '!&1l1 Division of Library and Archives 1989 Copyright © by Minnesota Historical Society The Oberholtzer Papers were microfilmed and this guide printed with funds provided by grants from the Ernest C. Oberholtzer Foundation and the Quetico-Superior Foundation. -.-- -- - --- ~?' ~:':'-;::::~. Ernest Oberholtzer in his Mallard Island house on Rainy Lake in the late 1930s. Photo by Virginia Roberts French. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society. Map of Arrowhead Region L.a"(.e~se\"C ~ I o A' .---.....; ., ; , \~ -'\ ~ • ~ fI"" i Whitefish---- Lake Fowl Lake ~/ ~ '""'-- F . O)"~"~'t\ ~~ , .tV "" , I -r-- ~Rlucr~ v'" '" Reprinted from Saving Quetico-Superior: A Land Set Apart, by R. Newell Searle, copyright@ 1977 by the Minnesota Historical Society, Used with permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .•• INTRODUCTION. 1 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 2 ARRANGEMENT NOTE 5 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS: Biographical Information 8 Personal Correspondence and Related Papers 9 Short Stories, Essays, and Other Writings 14 Miscellaneous Notes. • • 19 Journals and Notebooks • 20 Flood Damage Lawsuit Files 34 Quetico-Superior Papers • 35 Wilderness Society Papers • 39 Andrews Family Papers •• 40 Personal and Family Memorabilia and Other Miscellany 43 ROLL CONTENTS LIST • 44 RELATED COLLECTIONS 48 PREFACE This micl'ofilm edition represents the culmination of twenty-five years of efforts to preserve the personal papers of Ernest Carl Oberholtzer, The acquisition, processing, conservation, and microfilming of the papers has been made possible through the dedicated work and generous support of the Ernest C, Oberholtzer Foundation and the members of its board. Additional grant support was received from the Quetico-Superior Foundation. -

Crossing Boundaries for the Border Lakes Region

Wilderness News FROM THE QUETICO SUPERIOR FOUNDATION FALL 2008 quetico superior country The Quetico Superior Foundation, established in 1946, encourages and supports the protection of the ecological, cultural and historical resources of the Quetico Superior region. Near Tettegouche State Park. Photo by Jim Gindorff. Crossing Boundaries for the “The loss of silence in our lives is a great tragedy of our civilization. Canoeing is one of the finest ministries that can Border Lakes Region happen.” By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor – Reverend Paul Monson, Board Member In an era of increasing partnership “It’s not that there aren’t other collaboratives that of the Listening Point Foundation and a in the Quetico Superior region, the are interested in similar types of objectives,” he strong believer in the restorative value of said. “I think one of the things that makes this col- camping and canoeing. Border Lakes Partnership provides laborative unique is that the interested parties got July, 24 1937 - October 28, 2008 a model for what cooperative together because of a sense of common purpose. In efforts can accomplish. other cases, some of these more collaborative groups that have worked across agencies have got- The collaborative has been at work since 2003 ten together because there’s been conflict or issues developing cross-boundary strategies for managing they needed to resolve.” forest resources, reducing hazardous forest fuels, and conserving biodiversity in the region. Members Shinneman, himself, embodies the shared nature like the U.S. Forest Service Northern Research of the Border Lakes Partnership’s efforts. “My posi- Station, Superior National Forest, Minnesota tion is really a unique one,” he said. -

Untrammeled WILDERNESS

Untrammeled WILDERNESS KEVIN PROESCHOLDT ?hkfZgrFbgg^lhmZglZg]hma^klZ\khllma^\hngmkr%Zoblbmmhhg^h_hnkgZmbhgÍl]^lb`& gZm^]pbe]^kg^llZk^ZlblZab`aeb`amh_ma^r^Zk'Ma^;hng]ZkrPZm^kl<Zgh^:k^ZPbe]^kg^ll !;P<:P"bgghkma^Zlm^kgFbgg^lhmZaZl[^^gma^gZmbhgÍlfhlmihineZkZg]fhlmoblbm^] ik^l^ko^_hk]^\Z]^l'Fbgg^lhmZZelhaZlmphe^ll^k&dghpg_^]^kZepbe]^kg^llZk^Zl3ma^:`Zl& lbsPbe]^kg^llg^ZkMab^_Kbo^k?Zeel%Zg]ma^MZfZkZ\Pbe]^kg^ll[r=^mkhbmEZd^l'Pabe^ ^__hkmlmh]^lb`gZm^Zk^Zlebd^ma^;P<:PZlpbe]^kg^llaZo^k^\^bo^]fn\ain[eb\Zmm^gmbhg% ma^lmhkrh_hg`hbg`lm^pZk]labiZg]ikhm^\mbhgblh_m^gg^`e^\m^]'* Ma^phk]ngmkZff^e^]blma^d^r]^l\kbimhkbgma^Pbe& fhk^maZg0))Zk^ZlZg]*)0fbeebhgZ\k^l':eeh_ma^l^ ]^kg^ll:\mh_*2/-maZm]^lb`gZm^]Zg]ikhm^\mlpbe]^k& Zk^ZlZk^`ho^kg^][rma^*2/-eZpZg]bmlfZg]Zm^mh g^llZk^ZlZ\khllma^\hngmkr%bg\en]bg`paZmblghpdghpg ikhm^\mma^\aZkZ\m^kh_ngmkZff^e^]pbe]^kg^ll' Zlma^;P<:P'Bgi^kaZilma^fhlmih^mb\iZllZ`^bgZgr _^]^kZelmZmnm^%mableZp^ehjn^gmer]^Ög^]Zpbe]^kg^ll ZlÊZgZk^Zpa^k^ma^^ZkmaZg]bml\hffngbmrh_eb_^Zk^ AhpZk]SZagbl^k%pahl^ko^]Zl^q^\nmbo^l^\k^mZkr ngmkZff^e^][rfZg%pa^k^fZgabfl^e_blZoblbmhkpah h_ma^Pbe]^kg^llLh\b^mr_khf*2-.mh*2/-%eZk`^er ]h^lghmk^fZbg'Ë=^libm^k^\^gmablmhkb\Zek^l^Zk\a%ma^ pkhm^ma^Pbe]^kg^ll:\mZg]inkihl^er\ahl^ma^phk] _neef^Zgbg`Zg]lhf^h_ma^bglibkZmbhg_hk\ahhlbg`mabl ngmkZff^e^]'Ma^l\aheZkerÊSZagb^%ËZlabl_kb^g]l mhn\almhg^phk]k^fZbgebmme^dghpghkng]^klmhh]'+ \Zee^]abf%eho^][hhdlZg]ebm^kZmnk^%mahn`am]^^ier Ma^*2/-Z\m%bgZ]]bmbhgmh]^Ögbg`pbe]^kg^ll Z[hnmpbe]^kg^lloZen^l%Zg]pZlZd^^gphk]lfbmabg Zk^ZlZg]fZg]Zmbg`ma^bkikhm^\mbhg%Zelh^lmZ[ebla^] ablhpgkb`am'A^^]bm^]ma^hk`ZgbsZmbhgÍlfZ`Zsbg^%Ma^ -

Can You Introduce Yourself and Tell Us How You Are Working with Wilderness?

INTERVIEW WITH EDWARD ZAHNISER BY LAURA BUCHHEIT and MARK MADISON AUGUST 11, 2004, NCTC, SHEPHERDSTOWN, WV MS. BUCHHEIT: Can you introduce yourself and tell us how you are working with wilderness? MR. ZAHNISER: I got into working with wilderness by accident of birth. My father Howard Zahniser worked for the Wilderness Society in Washington, D.C. from a few months before my birth in 1945 until his death in 1964. I grew up among the people of the early Wilderness Society and the early wilderness movement. And just as any young kid growing up would, I merely thought of these people as my father’s associates and people who showed up in Washington occasionally. We lived in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, in Maryland. But we spent many summers in the wilderness of the Adirondacks, and later in other wild areas throughout the country. At age 15 I was able to go to the Sheenjek country in Alaska—in what is now part of the Artic National Wildlife Refuge—with Olaus and Mardy Murie. From there we went down to what is now Denali National Park and Preserve with Adolph and Louise Murie. It was then Mount McKinley National Park, Adolph was in Denali working on his book on Alaska bears then, so we had a couple of weeks there in Mount McKinley National Park. That was probably the most influential summer of my life. From that trip, when I got back to the Washington area, I just went up to the Adirondacks with my mother and one of my siblings for the rest of the summer. -

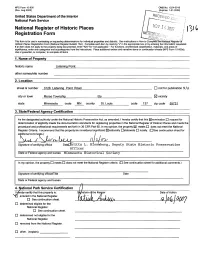

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug 2002) (Expires: 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places -2007 Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to CompleWiri^^tionA[-Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Listening Point other names/site number 2. Location street & number 3128 Listening Point Road D not for publication N/A city or town Morse Township Ely vicinity state Minnesota code MN county St. Louis code 137 zip code 55731 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property Exl meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant ^nationally Qstatewide D locally. -

A Century of Wilderness Preservation Rainy Lake Watershed Area

A Century of Wilderness Preservation in the Rainy Lake Watershed Area Prepared by the Rainy Lake Conservancy Photograph by Mary E. Lysne The Rainy Lake Watershed, often referred to as the Quetico-Superior region, is an immense area of 14,500 square miles. Illustration from the Oberholtzer Foundation A CENTURY OF WILDERNESS PRESERVATION IN THE RAINY LAKE WATERSHED AREA Introduction The Rainy Lake Watershed is an immense area of 14,500 square miles between Lake of the Woods and Lake Superior. Often referred to as the Quetico-Superior region, it is a unique meeting place of three great North American ecosystems: the boreal, the Great Lakes-St.Lawrence, and the prairie. Although the following summary outlines major events in the struggle to preserve the wilderness qualities of the entire region, greater emphasis has been placed on the Canadian side of the border. (References for detailed accounts of the history of the conservation movement in the Quetico- Superior area are listed at the end of the summary.) Background Scholars agree that prehistoric aboriginal peoples inhabited the Rainy Lake area approximately 10,000 years ago. By the time the French explorers arrived in the 1600s, Sioux and later Ojibwe (Chippewa) tribes were living in the region. With the explorers came the famous voyageurs who symbolized fur trading and the spirit of Quetico- Superior country. Eventually fur trading waned and was replaced in the 1880s by gold and iron mining. For a short time, gold mines at Mine Centre and the Little America Mine on Rainy Lake flourished. Finally, in the last decades of the century, mining settlements triggered big tree logging in Minnesota and Ontario. -

The War Against Nature: Benton Mackaye's Regional Planning

THE WAR AGAINST NATURE: BENTON MACKAYE’S REGIONAL PLANNING PHILOSOPHY AND THE PURSUIT OF BALANCE by Julie Ann Gavran APPROVED BY SUPERVISORY COMMITTEE: ___________________________________________ Eric R. Schlereth, Chair ___________________________________________ Matthew J. Brown ___________________________________________ Pamela S. Gossin ___________________________________________ Peter K. J. Park Copyright 2017 Julie Ann Gavran All Rights Reserved THE WAR AGAINST NATURE: BENTON MACKAYE’S REGIONAL PLANNING PHILOSOPHY AND THE PURSUIT OF BALANCE by JULIE ANN GAVRAN, BA, MA DISSERTATION Presented to the Faculty of The University of Texas at Dallas in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HUMANITIES – HISTORY OF IDEAS THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS May 2017 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have received tremendous support from many individuals in the past thirteen years. Drs. John Marazita and Ron Carstens have been mentors, colleagues, and friends from my early academic beginning at Ohio Dominican University. I would especially like to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Eric Schlereth, for providing me with the final push and guidance to complete this project. I would like to thank the rest of my committee, Drs. Matthew Brown, Pamela Gossin, and Peter Park, for your support throughout the many years of coursework and research, and for helping lay the foundation of this project. I would like to thank the countless people I spoke to throughout the many years of research, especially the staff at Rauner Special Collections Library at Dartmouth College, the Appalachian Trail Conservancy, and the many people who knew Benton personally. Finally, thanks to Drs. Jim Cannici and Gabe Yeamans for providing me lending ears and hearts without which I could not have finished this project. -

North Cascades Conservation Council

NORTH CASCADES CONSERVATION COUNCIL Volume II September 195&* Number 9 "To secure the support of the people and the government in the protection and preservation of scenic, scientific, wildlife, wilderness, and outdoor recreational resource values in the North Cascades " In this issue: Wilderness Society Council Meet., 1 Riley, Again 3 Washingtons Tnird National Park? 3 Wilderness Bill Hearings 5 John Osseward -"Grass Roots Support" 6 What Other Editors Say 6 Mount Rainier Accomodations Studied g National Park Idea Spreads g Promises Mean Nothing 9 Martin Litton Comment 10 New Members 9 Trail Trips for the Pall 10 STEHBKIN, WASHINGTON, EASTERN GATEWAY TO THE MAGNIFICENT NORTHERN CASCADES WAS THE SCENE OE THE 13th ANNUAL MEETING OE THE COUNCIL OP THE WILDERNESS SOCIITTY Saturday evening, August 23rd, 12 of the 15 members of the Council of the Wilderness Society met at Golden West Lodge in Stehekin for a ^-day conference to be followed by a pack trip into the mountains nearby. Invited guests swelled the number who attended to UO or so people and all were active participants in the 3 days allotted to open sessions. It was a very lively, inspiring meeting and your editor felt humbled among the assemblago of wilderness conservationists who were present. Following are some of the topics discussed, not necessarily listed in order. The Wilderness Council was responsible for the meeting, however, represent atives from the National Park Service, Forest Service, Wildlife Federation, National Parks Association, Student Conservation Program, Federation of Western Outdoor Clubs, Trustees for Conservation, North Cascades Conserservation Council, Washington State Sportsman's Council, Olympic Park Associates, Recreation Unlimited, Sierra Club, Seattle Mountaineers, Wenatcheo Alpine Roamers, Yakima Cascadians, and representatives of other groups interest in wilderness preservation attended. -

The Historic Lodges of the Boundary Waters

Wilderness News FROM THE QUETICO SUPERIOR FOUNDATION SPRING 2004 Special Feature Part II: The Historic Lodges of the Boundary Waters By Kari Finkler, Wilderness News Contributor quetico superior country The Quetico Superior Foundation, [Part I of this story appeared in the Fall 2003 issue of established in 1946, encourages and Wilderness News] supports the protection of the ecological, cultural and historical resources of the The Big Resorts – Basswood Lake, Quetico Superior region. Crooked Lake Throughout the 1930s, tourism spread rapidly into “The movement of a canoe is like a reed in the roadless areas in the east from Grand Marais, the wind. Silence is part of it, and the and in the west from Ely, where Basswood Lake sounds of lapping water, bird songs, and became a primary destination. It was reachable by the wind in the trees. It is part of the seaplane, boat, or by a combination of rough roads medium through which it floats, the sky, Wegen’s Wilderness Camp, 1931. Photo courtesy Doris and motorized portage. Basswood offered easy Wegen Patton the water, the shores...When a man is part access to fishing on both sides of the Canada/MN of his canoe, he is part of all that canoes border, and a network of islands and secluded They ranged from single-cabin establishments to have ever known.” bays. By the late 1950s there were more than 20 multi-cabin resorts. In addition to numerous pri- resorts on Basswood alone, and at least two suc- vate cabins and resorts, several ‘corporate retreats’ – Sigurd F. Olson, The Singing Wilderness cessful resorts thrived on nearby Crooked Lake, were built as well. -

Massachusetts Contributions to National Forest Conservation Other Creatures, and Why Different Seedlings Then Prospered Under Knowable Circumstances

Massachusetts Contributions to JVational $orest Conseroation STEPHEN FOX c:r'ow ARD THE END of the nineteenth century, Massachusetts for L ;sts helped inspire and launch what later became known as the environmental movement. When the implacable processes of modern ization and industrialization reached a certain point - replacing older powers of wind, water, and muscle with coal, petroleum, steam, and electricity, and pulling rural residents from their farms into burgeoning urban centers to work in shops and factories - a few individuals in Massachusetts and elsewhere began to rethink the assumptions under pinning modern progress. Balancing the gains and losses, these re thinkers increasingly focused on the heedless wastes and unintended, baleful side effects of their era's general rush to industrialize. Some aspects of the natural world, they accordingly urged, should be guarded from the relentless whoosh of modernity. In particular, dedicated friends of Massachusetts trees and woodlands helped create a national movement for forest conservation: both to protect some trees abso lutely from human use, and to advocate more prudent commercial forestry and timber cutting. By slow degrees, and just in time, Massa chusetts forests found their defenders -with rippling effects on forest policies at the national level. This chapter highlights four individuals and two organizations, all bred and based in Massachusetts, that were active in forest conservation from the mid-18oos to the mid-19oos. Many other significant people and conservation groups could have been included here; the state has produced a long, honorable line of conservationists. But for this chap ter the roster has been winnowed by the dual criteria of originality and national influence.