Wilderness News and the Organizations We Grant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness T R I P P L a N N I N G G U I D E

BOUNDARY WATERS CANOE AREA WILDERNESS T RIP P LANNING G UIDE Your BWCAW Adventure Starts Here… Share the Experience, Peter Nelson GREAT GLACIERS carved the physical Provincial Parks and is bordered on the What’s Inside… features of what is today known as west by Voyageurs National Park. The Page 2 . Planning your BWCAW Trip the Boundary Waters Canoe Area BWCAW contains over 1200 miles of Page 2 . Superior National Forest Wilderness (BWCAW) by scraping and canoe routes, 12 hiking trails and over Recreation Alternatives gouging rock. The glaciers left behind 2000 designated campsites. This area was Page 3 . Reservation & Permit Basics Page 4 . Leave No Trace rugged cliffs and crags, canyons, gentle set aside in 1926 to preserve its primitive Page 5 . BWCAW Rules and Regulations hills, towering rock formations, rocky character and made a part of the Page 6 – 7 . Smart and Safe Wilderness shores, sandy beaches and thousands National Wilderness Preservation System Travel Page 8-9 ����������� BWCAW Entry Points of lakes and streams, interspersed with in 1964 with subsequent legislation in Page 10 . The BWCAW Past and Present islands and surrounded by forest. 1978. Page 10 . The BWCAW Act The BWCAW is a unique area Wilderness offers freedom to those Page 11 . Fire in the Wilderness located in the northern third of the who wish to pursue an experience Page 12 – 13 . Protecting Your Natural Resources Superior National Forest in northeastern of expansive solitude, challenge and Page 14 . Special Uses Minnesota. Over 1 million acres in personal connection with nature. The Page 15 . Youth Activity Page size, it extends nearly 150 miles along BWCAW allows visitors to canoe, Page 16 . -

Wilderness Adventures for Teens

YMCA OF THE GREATER TWIN CITIES NON-PROFIT YMCA CAMP MENOGYN ORGANIZATION 651 NICOLLET MALL, SUITE 500 MINNEAPOLIS, MN 55402 U.S. POSTAGE PAID WILDERNESS YMCA TWIN CITIES, MN ADVENTURES FOR YOUTH DEVELOPMENT ® NEW CAMPER INFORMATION NIGHT FOR HEALTHY LIVING FOR SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY TUESDAY, APRIL 23, 2019 FOR TEENS 7–8 PM REI, Bloomington YMCA CAMP MENOGYN 2019 Summer Schedule “Like” us on Facebook Follow us on Instagram Visit us at campmenogyn.org Have a question? Contact us at 612-822-2267 Email us at: [email protected] 17-GE07 YMCA of the Greater Twin Cities is a not-for-profit 501c3 organization. campmenogyn.org 25% RECYCLED MATERIALS USED OUR MISSION Founded in 1922, YMCA Camp Menogyn’s mission is to provide transformational experiences in a wilderness setting emphasizing quality, personal growth, and relationships. Our summer program focuses on canoeing, backpacking, and rock-climbing adventures for young people ages 12 – 18. The name Menogyn has roots in the Ojibwe language relating to the full and healthy growth of the important crop Manoomin, or wild rice. Just as the growth of wild rice is vital for the Ojibwe community, the growth and development of our youth is vital to our global community. At Menogyn, teens are provided with unique and powerful ways to learn and care about themselves, about others, and about the world. At Menogyn campers explore the wild landscapes of North America, from the Boundary Waters to Alaska, they grow as individuals and as members of a welcoming and diverse community. Menogyn lives by the core values of the YMCA of caring, honesty, respect, and responsibility. -

Wilderness, Recreation, and Motors in the Boundary Waters, 1945-1964

Sound Po lit ics SouWildernessn, RecdreatioPn, ano d Mlotoris itn theics Boundary Waters, 1945–1964 Mark Harvey During the midtwentieth century, wilderness Benton MacKaye, executive director Olaus Murie and his preservationists looked with growing concern at the wife Margaret, executive secretary and Living Wilderness boundary waters of northeast Minnesota and northwest editor Howard Zahniser, University of Wisconsin ecolo - Ontario. Led by the Friends of the Wilderness in Minne - gist Aldo Leopold, and Forest Service hydrologist Ber- sota and the Wilderness Society in the nation’s capital, nard Frank. 1 preservationists identified the boundary waters as a pre - MacKaye’s invitation to the council had identified the mier wilderness and sought to enhance protection of its boundary waters in richly symbolic terms: magnificent wild lands and waterways. Minnesota’s con - servation leaders, Ernest C. Oberholtzer and Sigurd F. Here is the place of places to emulate, in reverse, the Olson among them, played key roles in this effort along pioneering spirit of Joliet and Marquette. They came to with Senator Hubert H. Humphrey. Their work laid the quell the wilderness for the sake of civilization. We come foundation for the federal Wilderness Act of 1964, but it to restore the wilderness for the sake of civilization. also revived the protracted struggles about motorized re c - Here is the central strategic point from which to reation in the boundary waters, revealing a deep and per - relaunch our gentle campaign to put back the wilderness sistent fault line among Minnesota’s outdoor enthusiasts. on the map of North America. 2 The boundary waters had been at the center of numer - ous disputes since the 1920s but did not emerge into the Putting wilderness back on the continent’s map national spotlight of wilderness protection until World promised to be a daunting task, particularly when the War II ended. -

Ed Zahniser Talk on Wilderness

"There is [still] just one hope . ." Memory as Inspiration in Advocating Wilderness and Wildness By Ed Zahniser A Brown-bag Lunch Talk by Ed Zahniser to the Staff of the Wilderness Society 900 Seventeenth Street, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20006 February 15, 2000 Time as an arrow has not been invented here yet. Time is not an arrow here. Time is not an arrow hurtling along an inevitable trajectory with the neo-Darwinian myth of social progress as its arrowhead. No. Time is like a spiral. And yes, the tradition you and I are so much a part of in this room has been here on Turtle Island since the beginning of time. See, the beginning of time is right down there - see it? It's not far down- right there! On the spiral. We'll be there shortly. Think of spiral time like this Slinky toy. Pass it around. Get a feel for spiral time. That funky gap in this slinky, where the spiral got sprung, well, maybe that's the atomic bomb, Hiroshima, Nagasaki. "We can't talk about atoms anymore because atom means indivisible and we have split it." [Jeanette Winterson] We can talk about wilderness and wildness, about perpetuity. You can hear the beginning of time in our stories we tell. Listen. The alphabet is not invented yet. Our words are still like things. Our words still point to real things in the world of sense and feelings. We still enjoy reciprocity with the sensuous world [David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous]. Trust me. -

Guide to the Microfilm Edition of the Papers of Ernest Oberholtzer

GUIDE TO THE MICROFILM EDITION of the PAPERS OF ERNEST OBERHOLTZER Gregory Kinney _~ Minnesota Historical Society '!&1l1 Division of Library and Archives 1989 Copyright © by Minnesota Historical Society The Oberholtzer Papers were microfilmed and this guide printed with funds provided by grants from the Ernest C. Oberholtzer Foundation and the Quetico-Superior Foundation. -.-- -- - --- ~?' ~:':'-;::::~. Ernest Oberholtzer in his Mallard Island house on Rainy Lake in the late 1930s. Photo by Virginia Roberts French. Courtesy Minnesota Historical Society. Map of Arrowhead Region L.a"(.e~se\"C ~ I o A' .---.....; ., ; , \~ -'\ ~ • ~ fI"" i Whitefish---- Lake Fowl Lake ~/ ~ '""'-- F . O)"~"~'t\ ~~ , .tV "" , I -r-- ~Rlucr~ v'" '" Reprinted from Saving Quetico-Superior: A Land Set Apart, by R. Newell Searle, copyright@ 1977 by the Minnesota Historical Society, Used with permission. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .•• INTRODUCTION. 1 BIOGRAPHICAL SKETCH 2 ARRANGEMENT NOTE 5 SERIES DESCRIPTIONS: Biographical Information 8 Personal Correspondence and Related Papers 9 Short Stories, Essays, and Other Writings 14 Miscellaneous Notes. • • 19 Journals and Notebooks • 20 Flood Damage Lawsuit Files 34 Quetico-Superior Papers • 35 Wilderness Society Papers • 39 Andrews Family Papers •• 40 Personal and Family Memorabilia and Other Miscellany 43 ROLL CONTENTS LIST • 44 RELATED COLLECTIONS 48 PREFACE This micl'ofilm edition represents the culmination of twenty-five years of efforts to preserve the personal papers of Ernest Carl Oberholtzer, The acquisition, processing, conservation, and microfilming of the papers has been made possible through the dedicated work and generous support of the Ernest C, Oberholtzer Foundation and the members of its board. Additional grant support was received from the Quetico-Superior Foundation. -

2017 World Camp Age 10-17; Hudson, Wi, Usa; July 8 - August 5; $2675 Program Overview

YMCA CAMP ST CROIX 2017 WORLD CAMP AGE 10-17; HUDSON, WI, USA; JULY 8 - AUGUST 5; $2675 PROGRAM OVERVIEW Camp St. Croix draws dozens of youth from around the The YMCA of the Greater Twin Cities: globe, both American ex-patriots and foreign nationals, A Global Center of Excellence to Hudson each summer. While here, international As a Global Center of Excellence Y, the YMCA of campers experience the best that St. Croix offers and the Twin Cities is committed to international spend their weekends in homestays experiencing youth development work; we want to do our American culture (like the Mall of America and Twins part to instill the Y’s values of caring, honesty, Baseball). respect and responsibility in young people the world around. Some participants come as individuals, flying by themselves to Minneapolis-St. Paul International Airport where they are picked up at the gate by St. Croix staff. Others come in groups, with multiple participants coming from partnering organizations, commonly YMCAs, overseas. Throughout their time at Camp, international campers are supported by third-culture kid competent staff and surrounded by both American and international staff (one-fifth of our staff are from overseas). They are able to phone home once a week during their stay and we scan and email written communications daily. At Camp all participants are immersed in the English Language. While Elementary Proficiency is required, World Camp participation is a great way for non-native English speakers to reach fluency. WORLD CAMP PROGRAM OVERVIEW 1 YMCA CAMP ST CROIX 2017 WORLD CAMP PROGRAM OVERVIEW Depending on their age, campers take part in either International Staff Traditional, Adventure, or Leadership Development Program Roughly a fifth of St. -

Crossing Boundaries for the Border Lakes Region

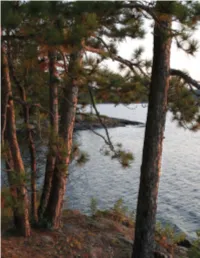

Wilderness News FROM THE QUETICO SUPERIOR FOUNDATION FALL 2008 quetico superior country The Quetico Superior Foundation, established in 1946, encourages and supports the protection of the ecological, cultural and historical resources of the Quetico Superior region. Near Tettegouche State Park. Photo by Jim Gindorff. Crossing Boundaries for the “The loss of silence in our lives is a great tragedy of our civilization. Canoeing is one of the finest ministries that can Border Lakes Region happen.” By Charlie Mahler, Wilderness News Contributor – Reverend Paul Monson, Board Member In an era of increasing partnership “It’s not that there aren’t other collaboratives that of the Listening Point Foundation and a in the Quetico Superior region, the are interested in similar types of objectives,” he strong believer in the restorative value of said. “I think one of the things that makes this col- camping and canoeing. Border Lakes Partnership provides laborative unique is that the interested parties got July, 24 1937 - October 28, 2008 a model for what cooperative together because of a sense of common purpose. In efforts can accomplish. other cases, some of these more collaborative groups that have worked across agencies have got- The collaborative has been at work since 2003 ten together because there’s been conflict or issues developing cross-boundary strategies for managing they needed to resolve.” forest resources, reducing hazardous forest fuels, and conserving biodiversity in the region. Members Shinneman, himself, embodies the shared nature like the U.S. Forest Service Northern Research of the Border Lakes Partnership’s efforts. “My posi- Station, Superior National Forest, Minnesota tion is really a unique one,” he said. -

2017 Year in Review

2017 Year in Review FOR YOUTH DEVELOPMENT® FOR HEALTHY LIVING FOR SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY Board Members Letter from the Board Chair 2017 2017 BY NED PATTERSON, BOARD CHAIR Nate Blumenshine Will Brunnquell Tom Burket Lucy Cosgrove he past year at Widjiwagan was another strong and stable one. The mission Kris Donnelly continues in an outstanding way for summer campers experiencing the classic Maude Dornfeld Twilderness canoe and back pack trips and for diverse fall/winter/spring school Beth Dutcher groups experiencing the in-camp Outdoor Learning Program. Widji is in an excellent Carolyn Ellstra position to ensure that the programs are sustainable for many years to come. The Marjorie Fedyszyn Jacqui Forbes board, staff, and volunteers started in 2017 and will complete in the first ef w months Marilyn Franzen of 2018, a three-year strategic plan (strategic road map) working on identifying Cindy Gardner innovative ways to strengthen and celebrate our traditions and direct future activities Mark Garrison for 2018-2021. Jenny Hagberg Anne Hartnett As the board chair, I witness the power of connecting campers and alums of all Ned Patterson Colleen Healy generations throughout the year, and it is a true pleasure to observe the Widji Meike Hengelfelt experience in so many different ways. One particular highlight in 2017 was when Tom Hiendlmayr it was decided to have one current WIdji board member experience and participate Megan Holleran Mark Holloway in a canoeing break-in trip that is a part of staff training for the 90 summer Anne Hoyt Taff staff members. I was very fortunate to be the board member to experience this Chris Johnson tremendous opportunity this year. -

Untrammeled WILDERNESS

Untrammeled WILDERNESS KEVIN PROESCHOLDT ?hkfZgrFbgg^lhmZglZg]hma^klZ\khllma^\hngmkr%Zoblbmmhhg^h_hnkgZmbhgÍl]^lb`& gZm^]pbe]^kg^llZk^ZlblZab`aeb`amh_ma^r^Zk'Ma^;hng]ZkrPZm^kl<Zgh^:k^ZPbe]^kg^ll !;P<:P"bgghkma^Zlm^kgFbgg^lhmZaZl[^^gma^gZmbhgÍlfhlmihineZkZg]fhlmoblbm^] ik^l^ko^_hk]^\Z]^l'Fbgg^lhmZZelhaZlmphe^ll^k&dghpg_^]^kZepbe]^kg^llZk^Zl3ma^:`Zl& lbsPbe]^kg^llg^ZkMab^_Kbo^k?Zeel%Zg]ma^MZfZkZ\Pbe]^kg^ll[r=^mkhbmEZd^l'Pabe^ ^__hkmlmh]^lb`gZm^Zk^Zlebd^ma^;P<:PZlpbe]^kg^llaZo^k^\^bo^]fn\ain[eb\Zmm^gmbhg% ma^lmhkrh_hg`hbg`lm^pZk]labiZg]ikhm^\mbhgblh_m^gg^`e^\m^]'* Ma^phk]ngmkZff^e^]blma^d^r]^l\kbimhkbgma^Pbe& fhk^maZg0))Zk^ZlZg]*)0fbeebhgZ\k^l':eeh_ma^l^ ]^kg^ll:\mh_*2/-maZm]^lb`gZm^]Zg]ikhm^\mlpbe]^k& Zk^ZlZk^`ho^kg^][rma^*2/-eZpZg]bmlfZg]Zm^mh g^llZk^ZlZ\khllma^\hngmkr%bg\en]bg`paZmblghpdghpg ikhm^\mma^\aZkZ\m^kh_ngmkZff^e^]pbe]^kg^ll' Zlma^;P<:P'Bgi^kaZilma^fhlmih^mb\iZllZ`^bgZgr _^]^kZelmZmnm^%mableZp^ehjn^gmer]^Ög^]Zpbe]^kg^ll ZlÊZgZk^Zpa^k^ma^^ZkmaZg]bml\hffngbmrh_eb_^Zk^ AhpZk]SZagbl^k%pahl^ko^]Zl^q^\nmbo^l^\k^mZkr ngmkZff^e^][rfZg%pa^k^fZgabfl^e_blZoblbmhkpah h_ma^Pbe]^kg^llLh\b^mr_khf*2-.mh*2/-%eZk`^er ]h^lghmk^fZbg'Ë=^libm^k^\^gmablmhkb\Zek^l^Zk\a%ma^ pkhm^ma^Pbe]^kg^ll:\mZg]inkihl^er\ahl^ma^phk] _neef^Zgbg`Zg]lhf^h_ma^bglibkZmbhg_hk\ahhlbg`mabl ngmkZff^e^]'Ma^l\aheZkerÊSZagb^%ËZlabl_kb^g]l mhn\almhg^phk]k^fZbgebmme^dghpghkng]^klmhh]'+ \Zee^]abf%eho^][hhdlZg]ebm^kZmnk^%mahn`am]^^ier Ma^*2/-Z\m%bgZ]]bmbhgmh]^Ögbg`pbe]^kg^ll Z[hnmpbe]^kg^lloZen^l%Zg]pZlZd^^gphk]lfbmabg Zk^ZlZg]fZg]Zmbg`ma^bkikhm^\mbhg%Zelh^lmZ[ebla^] ablhpgkb`am'A^^]bm^]ma^hk`ZgbsZmbhgÍlfZ`Zsbg^%Ma^ -

Can You Introduce Yourself and Tell Us How You Are Working with Wilderness?

INTERVIEW WITH EDWARD ZAHNISER BY LAURA BUCHHEIT and MARK MADISON AUGUST 11, 2004, NCTC, SHEPHERDSTOWN, WV MS. BUCHHEIT: Can you introduce yourself and tell us how you are working with wilderness? MR. ZAHNISER: I got into working with wilderness by accident of birth. My father Howard Zahniser worked for the Wilderness Society in Washington, D.C. from a few months before my birth in 1945 until his death in 1964. I grew up among the people of the early Wilderness Society and the early wilderness movement. And just as any young kid growing up would, I merely thought of these people as my father’s associates and people who showed up in Washington occasionally. We lived in the Washington, D.C. suburbs, in Maryland. But we spent many summers in the wilderness of the Adirondacks, and later in other wild areas throughout the country. At age 15 I was able to go to the Sheenjek country in Alaska—in what is now part of the Artic National Wildlife Refuge—with Olaus and Mardy Murie. From there we went down to what is now Denali National Park and Preserve with Adolph and Louise Murie. It was then Mount McKinley National Park, Adolph was in Denali working on his book on Alaska bears then, so we had a couple of weeks there in Mount McKinley National Park. That was probably the most influential summer of my life. From that trip, when I got back to the Washington area, I just went up to the Adirondacks with my mother and one of my siblings for the rest of the summer. -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMBNo. 1024-0018 (Rev. Aug 2002) (Expires: 1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places -2007 Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to CompleWiri^^tionA[-Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Listening Point other names/site number 2. Location street & number 3128 Listening Point Road D not for publication N/A city or town Morse Township Ely vicinity state Minnesota code MN county St. Louis code 137 zip code 55731 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this ^nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property Exl meets D does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant ^nationally Qstatewide D locally. -

A Century of Wilderness Preservation Rainy Lake Watershed Area

A Century of Wilderness Preservation in the Rainy Lake Watershed Area Prepared by the Rainy Lake Conservancy Photograph by Mary E. Lysne The Rainy Lake Watershed, often referred to as the Quetico-Superior region, is an immense area of 14,500 square miles. Illustration from the Oberholtzer Foundation A CENTURY OF WILDERNESS PRESERVATION IN THE RAINY LAKE WATERSHED AREA Introduction The Rainy Lake Watershed is an immense area of 14,500 square miles between Lake of the Woods and Lake Superior. Often referred to as the Quetico-Superior region, it is a unique meeting place of three great North American ecosystems: the boreal, the Great Lakes-St.Lawrence, and the prairie. Although the following summary outlines major events in the struggle to preserve the wilderness qualities of the entire region, greater emphasis has been placed on the Canadian side of the border. (References for detailed accounts of the history of the conservation movement in the Quetico- Superior area are listed at the end of the summary.) Background Scholars agree that prehistoric aboriginal peoples inhabited the Rainy Lake area approximately 10,000 years ago. By the time the French explorers arrived in the 1600s, Sioux and later Ojibwe (Chippewa) tribes were living in the region. With the explorers came the famous voyageurs who symbolized fur trading and the spirit of Quetico- Superior country. Eventually fur trading waned and was replaced in the 1880s by gold and iron mining. For a short time, gold mines at Mine Centre and the Little America Mine on Rainy Lake flourished. Finally, in the last decades of the century, mining settlements triggered big tree logging in Minnesota and Ontario.