Hevajratantra

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Getting to Know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism

THE FOUR ORDERS: BOOK EXCERPT Getting to know the Four Schools of Tibetan Buddhism hundreds ofyears that the four main been codified by Tibetan intellectual historians, who categorize Buddha's teachings in terms of three distinct of Tibetan Buddhism — Nyingma, vehicles — the Lesser Vehicle (Hinayana), the Great Vehicle akya, and Gelug — have evolved out of (Mahayana), and the Vajra Vehicle (Vajrayana) — each of which was intended to appeal to the spiritual capacities of their common roots in India, a wide array of particular groups. divergent practices, beliefs, and rituals have • Hinayana was presented to people intent on personal salvation in which one transcends come into being. However, there are signifi- suffering and is liberated from cyclic existence. • The audience of Mahayana teachings included cant underlying commonalities between the trainees with the capacity to feel compassion for different traditions, such as the importance the sufferings of others who wished to seek awakening in order to help sentient beings over- of overcoming attachment to the phenomena come their sufferings. of cyclic existence, and the idea that it is • Vajrayana practitioners had a strong interest in the welfare of others, coupled with determination necessary for trainees to develop an attitude to attain awakening as quickly as possible, and the spiritual capacity to pursue the difficult practices of sincere renunciation. John Powers' fasci- of tantra. nating and comprehensive book, Introduction Indian Buddhism is also commonly divided by scholars of the four Tibetan orders into four main schools of tenets to Buddhism, re-issued by Snow Lion in — Great Exposition School, Sutra School, Mind Only School, September 2007, contains a lucid explanation and Middle Way School. -

Under Memberships

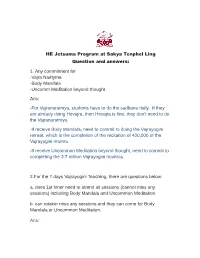

HE Jetsuma Program at Sakya Tenphel Ling Question and answers: 1. Any commitment for -Vajra Nairtyma -Body Mandala -Uncomm Meditation beyond thought Ans: -For Vajranaratmya, students have to do the sadhana daily. If they are already doing Hevajra, then Hevajra is fine, they don’t need to do the Vajranaratmya. -If receive Body Mandala, need to commit to doing the Vajrayogini retreat, which is the completion of the recitation of 400,000 of the Vajrayogini mantra. -If receive Uncommon Meditation beyond thought, need to commit to completing the 3.7 million Vajrayogini mantras. 2.For the 7 days Vajrayogini Teaching, there are questions below: a. does 1st timer need to attend all sessions (cannot miss any sessions) including Body Mandala and Uncommon Meditation. b. can retaker miss any sessions.and they can come for Body Mandala or Uncommon Meditation. Ans: a. Students who want to receive the proper transmission should attend all the sessions. However, if they don’t wish to receive the commitments of retreat and mantra accumulation (3.7 million), as is required if receive the body mandala and uncommon meditation beyond thought, they can skip those relevant sessions. b. For old timers who received the entire set before, it is their choice. However, Jetsun Kushok thinks it is beneficial to receive the teachings in its entirety without selectively choosing and skipping. 3.a For those new ones who.has taken 2 days Vajra Nairatyma empowerment, can they continue to take Vajrayogini Chin Lab and then go to the 7 days teaching? b. For those who.have taken 2 days Hevajra cause empowerment, they can come for Vajra Nairatyma empowerment and no need be one of the 25 new takers. -

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature

Chapter II * Place of Hevajra Tantraj in Tantric Literature 4 1. Buddhist Tantric Literature Lama Anagarik Govinda wrote: “the word ‘Tantrd is related to the concept of weaving and its derivatives (thread, web, fabric, etc.), hinting at the interwovenness of things and actions, the interdependence of all that exists, the continuity in the interaction of cause and effect, as well as in spiritual and'traditional development, which like a thread weaves its way through the fabric of history and of individual lives. The scriptures which in Buddhism go under the name of Tantra (Tib.: rgyud) are invariably of a mystic nature, i.e., trying to establish the inner relationship of things: the parallelism of microcosm and macrocosm, mind and universe, ritual and reality, the world of matter and the world of the spirit.”99 Scholars like N.N. Bhattacharyya and also Pranabananda Jash, regard Tantra as a religious system or science (Sastra) dealing with the means (sadhana) of attaining success (siddhi) in secular or religious efforts.100 N.N. Bhattacharyya mentions that “Tantra came to mean the essentials of any religious system and, subsequently, special doctrines and rituals found only in certain forms of various religious systems. This change in the meaning, significance, and character of the word ‘Tantra' is quite striking and is likely to reveal many hitherto unnoticed elements that have characterised the social fabric of India through the ages.”101 It is must be noted that the Tantrika tradition is not the work of a day, it has a long history behind it. Creation, maintenance and dissolution, 99 Lama Anagarika Govinda, Foundations of Tibetan Myticism (Maine: Samuel Weiser, Inc., 1969), p.93. -

Chinese and Tibetan Tantric Buddhism

THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY OF JERUSALEM THE ISRAEL INSTITUTE FOR ADVANCED STUDIES International Research Conference of the Israel Institute for Advanced Studies (IIAS) and the Israel Science Foundation with additional support from the Louis Freiberg Center for East Asian Studies and the Confucius Institute, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem CHINESE AND TIBETAN TANTRIC BUDDHISM June 16-18, 2014 All lectures will take place at the Feldman Building, on the Edmond J. Safra, Givat Ram Campus, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem Organizers: Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University) Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University) PROGRAM Monday, June 16 9:30 Gathering 10:00 Greetings: Michal Linial (Director, IIAS) 10:30-12:00 ESOTERIC BUDDHISM AND CHINESE RELIGION Robert H. Sharf (University of California, Berkeley) Esoteric Buddhist Influence on the Emergence of Chan in Eighth Century China Meir Shahar (Tel Aviv University & IIAS) The Tantric Origins of the Horse King: Hayagrīva and the Chinese Horse Cult Vincent Durand-Dastès (INALCO, Centre d’études chinoises, Equipe ASIEs, Paris) Esoteric Buddhism, Violence and Salvation in Ming-Qing Vernacular Novels 12:00-13:30 Lunch break 13:30-15:00 TIBETAN TANTRIC SCRIPTURES Jacob P. Dalton (University of California, Berkeley) Observations on the Ārya-tattvasaṃgraha-sādhanopāyikā and Its Commentary from Dunhuang Yael Bentor (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem & IIAS) Conflicting Positions over the Interpretation of the Body Maṇḍala Jampa Samten (Central University for Tibetan Studies, Varanasi & IIAS) The Secret Signs (Chommaka) -

Self-Initiation Text

The Quick Path to Great Bliss: The Uncommon Sadhana of Venerable Vajrayogini Naro Khechari Together with the Self-Initiation Ritual, The Mandala Rite, Banquet of Great Bliss Arranged Simply and Clearly for the Sake of Easy Verbal Recitation Even if you have received [a highest yoga tantra] initiation and the blessing [initiation] of Vajrayogini, if you have not received the profound instructions on the two stages, refrain from reading this. With great respect, I prostrate to the feet of the guru, inseparable from Venerable Vajrayogini. With your great compassion, please care for me. A. Prepara@on Yogas 1, 2, and 3 To start, perform the first yoga of sleeping, the second yoga of waking, and the third yoga of tas@ng nectar. 4. Yoga of Immeasurables Sit with the physical essen@als [of the seven-fold posture] and recite: Dün gyi nam khar la ma khor lo dom pa yab yum la tsa gyü kyi la ma yi dam chhog sum ka dö sung mäi tshog kyi kor nä zhug par gyur In the space before me are Guru Chakrasamvara father and mother, encircled by the assemblies of root and lineage gurus, yidams, the Three Jewels, Dharma protectors, and guardians. Taking Refuge Imagine yourself and all sen@ent beings going for refuge: Dag dang dro wa nam khäi tha dang nyam päi sem chän tham chä dü di nä zung te ji si jang chhub nying po la chhi kyi bar du I and all living beings, equaling the limits of space, from now unAl reaching the essence of enlightenment, Päl dän la ma dam pa nam la kyab su chhi o Go for refuge to the glorious holy gurus; Dzog päi sang gyä chom dän dä nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the complete buddha bhagavans; Dam päi chhö nam la kyab su chhi o We go for refuge to the holy Dharma; Phag päi gen dün nam la kyab su chhi o (3x) We go for refuge to the arya Sangha. -

A Brief Summary of the History of Hevajra in Cambodia

Spencer Ames 2/19/19 A Brief Summary of the History of Hevajra in Cambodia The Khmer kingdom (12th – 13th century): King Jayavarman VII and his Wife Indradevi. I first encountered the ruins of Cambodia’s ancient kingdoms on a family trip many years ago. My brother and I were climbing through thick vines and over giant tree roots entwining ancient carved stones. There were Buddha images throughout the intricately carved ruins, most of them decapitated or worn down to being almost unrecognizable by time and the overgrown jungle. I was a Buddhist myself and these ruins spoke to me at a deep level. My little bit of research at that time into these amazing ruins hinted that the Mahayana and Vajrayana were once practiced there. Twelve years passed and I found myself about to move to Cambodia for a year, and my initial curiosity was sparked again. While living there I dove into whatever research I could find on ancient and modern Buddhism in Cambodia and discovered a surprising link to my own Drikung Kagyu Tibetan Buddhist lineage. In the 12-13th century in Cambodia, and perhaps up to a few centuries before that, the Heruka tantras of Hevajra and Chakrasamvara made their way to the Khmer kingdom in Cambodia. There is little information that has survived to the present from these Vajrayana lineages, due to the secret nature of the teachings, and later to a nearly complete suppression and destruction of Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism by successive Hinayana, Hindu and Communist rulers. The small amount of information we do know primarily comes to us from the time of King Jayavarman VII (1125–1218 AD) who is generally considered Cambodia’s most famous and powerful king. -

Readingsample

Contributions to Tibetan Studies 6 Hevajra and Lam’bras Literature of India and Tibet as Seen Through the Eyes of A-mes-zhabs Bearbeitet von Jan-Ulrich Sobisch 1. Auflage 2008. Buch. ca. 264 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 89500 652 4 Format (B x L): 17 x 24 cm Gewicht: 616 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Religion > Buddhismus > Tibetischer Buddhismus Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. General introduction to the transmission of the Hevajra teachings In the following, I would like to provide an introduction to this study of the Hevajra teachings (and subsequent to that to the Path with Its Fruit teachings) that is accessible to both those who do read the Tibetan language and those who do not. I have therefore abstained in these two introductory chapters from using the regular Wylie transliteration of Tibetan names, and I have translated an abbreviated form of all titles of Tibetan works mentioned. I am sure that all names, which I have rendered here in an approximate phonetic transliteration, will be easily recognizable to the expert. To ensure, furthermore, the expert’s recognition of the translated titles of works, I have added the Tibetan abbreviated form of titles in Wylie transcription in brackets. For all bibliographical references, please refer to the main part of the book. -

Esoteric Buddhist Ritual Objects of the Koryŏ Dynasty (936-1392): Vajra

Esoteric BuddhistRitual Objectsof the KoryŏDynasty(936-1392): VajraSceptersand VajraBells NellyGeorgieva-Russ,AcademyofKoreanStudies The EsotericBuddhist tradition,knowninKoreaas milgyo ,or secretteaching,has playedimportant role in the history of KoreanBuddhism.Esoteric cults andpractices relatedtoMahayana Buddhism were supposedly present on the Korean peninsula since the introduction of Buddhism in 372 CE. Sutras with esoteric content, such as the Bhaisajyaguru Sutra, the Saddharmapundarika Sutra, Suvarnaprabhasa Sutra etc.,as well as dharani sutras were widely spreadduring the Three Kingdoms period(300-668CE) 1.Esoteric Buddhism was supportedby the royal court bothinthe UnifiedSilla (668-935) and Kory ŏ (918-1392) periods in connection with hoguk pulgyo (Buddhism as National Protector), its rites called to miraculously protect the nation against foreign invaders. Esoteric Buddhism, more than any other Buddhist school, is concernedwith worldly needs thus establishing a link between Buddhist spirituality and secular powers. Nevertheless, the absence of an established esoteric school paralleling the ZhenyaninChina andShingonin Japan andthe unarticulatedpresence of Esoteric beliefs and practices within such all-pervadingly influential sects as S ŏn or Pure Land Buddhism inKorea has leadtothe marginal positionof this fieldinBuddhist studies,bothinKorea andthe West.At the same time,eventhe scarce data onearly KoreanBuddhism reveals its profound influenceduringtheSillaandKory ŏdynasties. Animportantfactor in the practice ofesoteric Buddhism during the Koryŏis the probable existence of two esoteric sects: the Sinin (Mudra) school and the Ch’ongji (Dhārani) school. Both denominations are first encountered in Samguk Yusa ,according to whichthe founding of the Ch’ongji school is associated with the Silla monk Hyet’ŏng. 2 Nevertheless, the main reliable historical data about this school is a number of records in Koryŏ-sa referring tothe twelve century and later,about temples belonging to the Ch’ongji sect where esoteric rituals were conducted. -

Melody of Dharma

Melody of Dharma An Introductory Teaching on Taking Refuge Buddha Nature by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin A teaching by H.E. Ratna Vajra Rinpoche Global Ecological Crisis: An Aspirational Prayer by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin A Publication of the Office of Sakya Dolma Phodrang Dedicated to the Dharma Activities of His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 2010 • No.3 CONTENTS 3 From The Editors 5 Chogye Trichen Rinpoche / Nalendra Monastery 6 Remembering Great Masters –– Virupa 8 Virupa's Dohakosa 14 Global Ecological Crisis: An Aspirational Prayer –– by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 16 Taking Refuge –– A teaching by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin (part 2) 22 Buddha Nature –– A teaching by H.E. Ratna Vajra Rinpoche 28 News From The Phodrang: Dungsey Akasha Rinpoche 29 The Khön Family 32 Dharma Activities 32 • His Holiness' Visit to Arunachal Pradesh 34 • His Holiness’ Russian and European Teaching Tour 46 • Lamdre in Kuttolsheim 57 Mahavairocana Puja –– A brief History by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin 59 Summer Retreat 59 His Holiness' Retreat House Publisher: The Office of Sakya Dolma Phodrang Editing Team: Executive Editor: Ani Jamyang Wangmo Mrs. Yang Dol Tsatultsang (Dagmo Kalden’s mother), Managing Editor: Patricia Donohue Danijela Stamatovic, Sherab Chöden , Supervising Editor: Terri Lee Rosemarie Hemscheidt Art Director/Designer: Chang Ming-Chuan Cover Photo: Nalendra Monastery, Tibet Photographs: Cristina Vanza From The Editors We are very pleased to welcome our readers to this, our third issue of Melody of Dharma, with a particularly warm greeting to our new subscribers. We wish to extend our heartfelt thanks to our sponsors, whose generosity made this issue possible, and to all those who have contributed to the magazine in one way or another. -

His Eminence Ratna Vajra Rinpoche

The International Buddhist Academy (IBA) in Kathmandu is launching a global training program that encompasses the Buddhist path in its entirety. This unique course is devised to provide Dharma practitioners of all levels of experience a systematic training focused mainly on the theory and practice of the Vajrayana path as transmitted by the founding masters of the Sakya school of Tibetan Buddhism. His Eminence Ratna Vajra Rinpoche, the elder son of His Holiness the 41st Sakya Trizin and one of the most important lineage holders living today, was requested to teach this program at the International Buddhist Academy, an ideal setting in Kathmandu for this intensive training course. In addition, IBA is establishing partnerships with selected Dharma centers on different continents to offer the first three years of this program to be taught by qualified lamas and guest teachers. Please contact IBA for more details. For further information on the program please visit: www.thecompletepath.com For information on IBA and registration please visit: www.internationalbuddhistacademy.org 17 23 Contact and registration: The Complete Path [email protected] A systematic training from Sutra to Tantra HIS EMINENCE RATNA VAJRA RINPOCHE 7-Year program from 2017-2023 2017 August 1 - August 26 Clarifying the Sage‘s Intent 2021 The second part of The Tree of Clear Realization August 1 - August 5 Introductory course with Khenpo Ngawang Jorden by Jetsün Dragpa Gyaltsen August 7 – August 26 Clarifying the Sage‘s Intent by the Great Sakya Pandita The second part of The Tree of Clear Realization was composed by Jetsün Dragpa Kunga Gyaltsen Gyaltsen, the younger brother of Sönam Tsemo. -

Principles of Tantra

Principles of Tantra His Holiness the Sakya Trizin Tsechen Kunchab Ling Publications Walden, New York Tsechen Kunchab Ling Publications First printed in January 2016 This booklet was prepared by His Holiness the Sakya Trizin’s devoted students, under the guidance of Venerable Khenpo Kalsang Gyaltsen, based on teachings originally published in Melody of Dharma. Chodrungma Dr. Kunga Chodron served as general editor. Jon Mark Fletcher did copy editing and layout. DeWayne Dean assisted with editing. Tulku Tsultrim Pelgyi sponsored the preparation of the booklet. By this merit, may His Holiness the Sakya Trizin’s precious life be long and his teachings flourish. There is no charge for this book. Donations to the publication fund are greatly appreciated and will help us to print more copies to distribute to others. Tsechen Kunchab Ling Temple of All-Encompassing Great Compassion Seat of His Holiness the Sakya Trizin in the United States 12 Edmunds Lane Walden, New York 12586 www.sakyatemple.org +1-301-906-3378 [email protected] Contents Finding the Spiritual Master 1 The Essence of Tantra 11 Embarking on the Tantric Path 27 Comparison of Tantra to Other Buddhist Schools 35 Finding the Spiritual Master Two kinds of beings inhabit this universe: inani- mate beings and animate ones. “Inanimate” refers to beings that have no mental feelings, like rivers and mountains and so forth, while “animate” refers to humans and all other beings that have mental feelings. We humans belong to the animate class of beings, and our mental feelings are very powerful. There are many different kinds of human beings in numerous races and various cultures, each with their own views and beliefs, but there is one thing common to all: the wish to be free from suffering and to experience happiness. -

Esoteric Buddhism in Mediaeval Maritime Asia

BIBLIOGRAPHY Abramson, S. 2008. Ethnic Identity in Tang China. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. Abu-Lughod, J. 1989. Before European Hegemony: The World System A.D. 1250–1350. New York: Oxford University Press. Abu Musa, M. 2000. Archaeological Survey Report, Munshiganj District. Dhaka: Department of Archae- ology, Minister of Cultural Affairs, Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh. Acharya, P.K. 1979. An Encyclopaedia of Hindu Architecture. New Delhi: Oriental Books Reprint Cor- poration. Acker, W.R.B. 1954–74. Some Tang and Pre-Tang text on Chinese Painting, Vol. 2. Leiden: Brill. Acri, A. 2006. ‘The Sanskrit-Old Javanese Tutur Literature from Bali. The Textual Basis of Śaivism in Ancient Indonesia’, Rivista di Studi Sudasiatici 1: 107–37. ———2010. ‘On Birds, Ascetics, and Kings in Central Java: Rāmāyaṇa Kakawin, 24.96–126 and 25’, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde/Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences of Southeast Asia 166: 475–506. ———2011a. Dharma Pātañjala: A Śaiva Scripture from Ancient Java Studied in the Light of Related Old Javanese and Sanskrit Texts. Groningen: Egbert Forsten Publishing. ———2011b. ‘More On Birds, Ascetics and Kings in Central Java: Kakawin Rāmāyaṇa, 24.111–115 and 25.19–22’, in A. Acri, H. Creese and A. Griffiths (eds.) From Laṅkā Eastwards; The Rāmāyaṇa in the Literature and Visual Arts of Indonesia, pp. 53–91. Leiden: KITLV Press. ———2014. ‘Birds, Bards, Buffoons, and Brahmans: (Re-)Tracing the Indic Origins of some Ancient and Modern Javano-Balinese Performing Characters’, Archipel 88: 13–70. ———2015. ‘Revisiting the cult of ‘‘Śiva-Buddha’’ in Java and Bali’, in C.