Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TRECENTO FRAGMENTS M Ichael Scott Cuthbert to the Department Of

T R E C E N T O F R A G M E N T S A N D P O L Y P H O N Y B E Y O N D T H E C O D E X a thesis presented by M ichael Scott Cuthbert t the Depart!ent " M#si$ in partia% "#%"i%%!ent " the re&#ire!ents " r the de'ree " D $t r " Phi% s phy in the s#b(e$t " M#si$ H ar)ard * ni)ersity Ca!brid'e+ Massa$h#setts A#'#st ,--. / ,--.+ Mi$hae% S$ tt C#thbert A%% ri'hts reser)ed0 Pr "0 Th !as F rrest 1 e%%y+ advisor Mi$hae% S$ tt C#thbert Tre$ent Fra'!ents and P %yph ny Bey nd the C de2 Abstract This thesis see3s t #nderstand h 4 !#si$ s #nded and "#n$ti ned in the 5ta%ian tre6 $ent based n an e2a!inati n " a%% the s#r)i)in' s #r$es+ rather than n%y the ! st $ !6 p%ete0 A !a( rity " s#r)i)in' s #r$es " 5ta%ian p %yph ni$ !#si$ "r ! the peri d 788-9 7:,- are "ra'!ents; ! st+ the re!nants " % st !an#s$ripts0 Despite their n#!eri$a% d !i6 nan$e+ !#si$ s$h %arship has )ie4 ed these s #r$es as se$ ndary <and "ten ne'%e$ted the! a%t 'ether= " $#sin' instead n the "e4 %ar'e+ retr spe$ti)e+ and pred !inant%y se$#%ar $ di6 $es 4 hi$h !ain%y ri'inated in the F% rentine rbit0 C nne$ti ns a! n' !an#s$ripts ha)e been in$ !p%ete%y e2p% red in the %iterat#re+ and the !issi n is a$#te 4 here re%ati nships a! n' "ra'!ents and a! n' ther s!a%% $ %%e$ti ns " p %yph ny are $ n$erned0 These s!a%% $ %%e$ti ns )ary in their $ nstr#$ti n and $ ntents>s !e are n t rea%%y "ra'!ents at a%%+ b#t sin'%e p %yph ni$ 4 r3s in %it#r'i$a% and ther !an#s$ripts0 5ndi)id#6 a%%y and thr #'h their )ery n#!bers+ they present a 4 ider )ie4 " 5ta%ian !#si$a% %i"e in the " #rteenth $ent#ry than $ #%d be 'ained "r ! e)en the ! st $are"#% s$r#tiny " the inta$t !an#s$ripts0 E2a!inin' the "ra'!ents e!b %dens #s t as3 &#esti ns ab #t musical style, popularity, scribal practice, and manuscript transmission: questions best answered through a study of many different sources rather than the intense scrutiny of a few large sources. -

Trecento Cacce and the Entrance of the Second Voice

1 MIT Student Trecento Cacce and the Entrance of the Second Voice Most school children today know the song “Row, Row, Row Your Boat” and could probably even explain how to sing it as a canon. Canons did not start off accessible to all young children, however. Thomas Marrocco explains that the early canons, cacce, were not for all people “for the music was too refined, too florid, and rhythmically intricate, to be sung with any degree of competence by provincial or itinerant musicians.”1 The challenge in composing a caccia is trying to create a melody that works as a canon. Canons today (think of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat,” Pachelbel's “Canon in D,” or “Frère Jacques”) are characterized by phrases which are four or eight beats long, and thus the second voice in modern popular canons enters after either four or eight beats. One might hypothesize that trecento cacce follow a similar pattern with the second voice entering after the first voice's four or eight breves, or at least after the first complete phrase. This is not the case. The factors which determine the entrance of the second voice in trecento cacce are very different from the factors which influence that entrance in modern canons. In trecento cacce, the entrance of the second voice generally occurs after the first voice has sung a lengthy melismatic line which descends down a fifth from its initial pitch. The interval between the two voices at the point where the second voice enters is generally a fifth, and this is usually just before the end of the textual phrase in the first voice so that the phrases do not line up. -

Early Fifteenth Century

CONTENTS CHAPTER I ORIENTAL AND GREEK MUSIC Section Item Number Page Number ORIENTAL MUSIC Ι-6 ... 3 Chinese; Japanese; Siamese; Hindu; Arabian; Jewish GREEK MUSIC 7-8 .... 9 Greek; Byzantine CHAPTER II EARLY MEDIEVAL MUSIC (400-1300) LITURGICAL MONOPHONY 9-16 .... 10 Ambrosian Hymns; Ambrosian Chant; Gregorian Chant; Sequences RELIGIOUS AND SECULAR MONOPHONY 17-24 .... 14 Latin Lyrics; Troubadours; Trouvères; Minnesingers; Laude; Can- tigas; English Songs; Mastersingers EARLY POLYPHONY 25-29 .... 21 Parallel Organum; Free Organum; Melismatic Organum; Benedica- mus Domino: Plainsong, Organa, Clausulae, Motets; Organum THIRTEENTH-CENTURY POLYPHONY . 30-39 .... 30 Clausulae; Organum; Motets; Petrus de Cruce; Adam de la Halle; Trope; Conductus THIRTEENTH-CENTURY DANCES 40-41 .... 42 CHAPTER III LATE MEDIEVAL MUSIC (1300-1400) ENGLISH 42 .... 44 Sumer Is Icumen In FRENCH 43-48,56 . 45,60 Roman de Fauvel; Guillaume de Machaut; Jacopin Selesses; Baude Cordier; Guillaume Legrant ITALIAN 49-55,59 · • · 52.63 Jacopo da Bologna; Giovanni da Florentia; Ghirardello da Firenze; Francesco Landini; Johannes Ciconia; Dances χ Section Item Number Page Number ENGLISH 57-58 .... 61 School o£ Worcester; Organ Estampie GERMAN 60 .... 64 Oswald von Wolkenstein CHAPTER IV EARLY FIFTEENTH CENTURY ENGLISH 61-64 .... 65 John Dunstable; Lionel Power; Damett FRENCH 65-72 .... 70 Guillaume Dufay; Gilles Binchois; Arnold de Lantins; Hugo de Lantins CHAPTER V LATE FIFTEENTH CENTURY FLEMISH 73-78 .... 76 Johannes Ockeghem; Jacob Obrecht FRENCH 79 .... 83 Loyset Compère GERMAN 80-84 . ... 84 Heinrich Finck; Conrad Paumann; Glogauer Liederbuch; Adam Ile- borgh; Buxheim Organ Book; Leonhard Kleber; Hans Kotter ENGLISH 85-86 .... 89 Song; Robert Cornysh; Cooper CHAPTER VI EARLY SIXTEENTH CENTURY VOCAL COMPOSITIONS 87,89-98 ... -

Madrigal, Lauda, and Local Style in Trecento Florence

Madrigal, Lauda, and Local Style in Trecento Florence BLAKE McD. WILSON I T he flowering of vernacular traditions in the arts of fourteenth-century Italy, as well as the phenomenal vitality of Italian music in later centuries, tempts us to scan the trecento for the earliest signs of distinctly Italianate styles of music. But while the 137 cultivation of indigenous poetic genres of madrigal and caccia, ac- corded polyphonic settings, seems to reflect Dante's exaltation of Italian vernacular poetry, the music itself presents us with a more culturally refracted view. At the chronological extremes of the four- teenth century, musical developments in trecento Italy appear to have been shaped by the more international traditions and tastes associated with courtly and scholastic milieux, which often combined to form a conduit for the influence of French artistic polyphony. During the latter third of the century both forces gained strength in Florentine society, and corresponding shifts among Italian patrons favored the importation of French literary and musical culture.' The cultivation of the polyphonic ballata after ca. 1370 by Landini and his contem- poraries was coupled with the adoption of three-part texture from French secular music, and the appropriation of certain French nota- tional procedures that facilitated a greater emphasis on syncopation, Volume XV * Number 2 * Spring 1997 The Journal of Musicology ? 1997 by the Regents of the University of California On the shift in patronage and musical style during the late trecento, see Michael P. Long, "Francesco Landini and the Florentine Cultural Elite," Early Music History 3 (1983), 83-99, and James Haar, Essays on Italian Poetry and Music in the Renaissance, 1350-1600 (Berkeley, CA, 1986), 22-36. -

Song As Literature in Late Medieval Italy Lauren Lambert Jennings A

TRACING VOICES: SONG AS LITERATURE IN LATE MEDIEVAL ITALY Lauren Lambert Jennings A DISSERTATION in Music Presented to the Faculties of the University of Pennsylvania in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2012 Supervisor of Dissertation Emma Dillon, Professor of Music and Chair of the Department Graduate Group Chairperson Timothy Rommen, Associate Professor of Music and Director of Graduate Studies Dissertation Committee Emily Dolan, Assistant Professor of Music Kevin Brownlee, Professor of Romance Languages Fabio Finotti, Mariano DiVito Professor of Italian Studies Tr acing Voices: Song as Literature in Late Medieval Italy © 2012 Lauren Lambert Jennings iii A cknowledgement I owe a deep debt of gratitude to all who have offered me guidance and assistance throughout my graduate studies at the University of Pennsylvania. First and foremost, this project could never have come to fruition without the support and encouragement of my advisor, Emma Dillon, who took me under her wing the moment I arrived in Philadelphia. Her seminars sparked my interest in the study of manuscripts as material objects and were the starting point for this project. I am especially grateful for the guidance she has offered throughout the dissertation process, reading drafts of the proposal, grant applications, and chapters. Her suggestions and comments have pushed me to clarify my thoughts and to investigate questions I might otherwise have left aside. The rest of my committee deserves recognition and many thanks as well. Emily Dolan has been an invaluable mentor as both a scholar and a teacher throughout my time at Penn. Outside of the music department, I am indebted to Kevin Brownlee for his constant support of my work and for his seminars, which helped to shape the literary side of my dissertation, as well as for his assistance with the translations in Chapter 1. -

La Caccia Nell'ars Nova Italiana

8. Iohannes Tinctoris, Diffinitorium musice. Un dizionario Il corpus delle cacce trecentesche rappresenta con «La Tradizione Musicale» è una collana promossa di musica per Beatrice d’Aragona. A c. di C. Panti, 2004, ogni probabilità uno dei momenti di più intenso dal Dipartimento di Musicologia e Beni Culturali pp. LXXIX-80 e immediato contatto tra poesia e musica. La viva- dell’Università di Pavia, dalla Fondazione Walter 9. Tracce di una tradizione sommersa. I primi testi lirici italiani cità rappresentativa dei testi poetici, che mirano Stauffer e dalla Sezione Musica Clemente Terni e 19 tra poesia e musica. Atti del Seminario di studi (Cre mona, alla descrizione realistica di scene e situazioni im- Matilde Fiorini Aragone, che opera in seno alla e 20 febbraio 2004). A c. di M. S. Lannut ti e M. Locanto, LA CACCIA Fonda zione Ezio Franceschini, con l’intento di pro- 2005, pp. VIII-280 con 55 ill. e cd-rom mancabilmente caratterizzate dal movimento e dalla concitazione, trova nelle intonazioni polifo- muovere la ricerca sulla musica vista anche come 13. Giovanni Alpigiano - Pierluigi Licciardello, Offi - niche una cassa di risonanza che ne amplifica la speciale osservatorio delle altre manifestazioni della cium sancti Donati I. L’ufficio liturgico di san Do nato di cultura. «La Tradizione Musicale» si propone di of- portata. L’uso normativo della tecnica canonica, de- Arezzo nei manoscritti toscani medievali, 2008, pp. VIII-424 NELL’ARS NOVA ITALIANA frire edizioni di opere e di trattati musicali, studi 8 finita anch’essa ‘caccia’ o ‘fuga’, per l’evidente me- con ill. a colori monografici e volumi miscellanei di alto valore tafora delle voci che si inseguono, si dimostra 16. -

Course Information Music 331 (Music History I: Music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance) - Winter 2004 Professor: Dr

Cal Poly SLO - Department of Music - Course Information Music 331 (Music History I: Music of the Middle Ages and Renaissance) - Winter 2004 Professor: Dr. Alyson McLamore Office Phone: 756-2612 Office: 132 Davidson Music Center Email: [email protected] Web Site: http://cla.calpoly.edu/~amclamor Office Hours: Mon 1:30-3; Tues 3-4; Wed 1:30-3; Thurs 3-4; other times by appointment—just ask! Course Description: During this course, we'll look at western Medieval and Renaissance art music from several perspectives: as individual masterworks, as representatives of various composers, as examples of particular styles and forms, as analytic 'problems,' and as artworks derived from changing social milieus. We'll emphasize the development of skills in talking and writing 'about' music. The course will include lectures and class discussions, assigned readings, written assignments, and periodic examinations. Required Course Materials: Books and Scores: Stolba, K Marie. The Development of Western Music: A History. Third Edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Stolba, K Marie, ed. The Development of Western Music: An Anthology - Volume I (From Ancient Times through the Baroque Era). Third Edition. Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Course Reader - available for a small fee from Dr. McLamore (from MU 320): Hacker, Diana. A Writer's Reference. 5th ed. Boston: Bedford Books, 2003. Listening Materials: Compact Disks to accompany The Development of Western Music: An Anthology - Volume I (From Ancient Times through the Baroque Era) (Third Edition), edited by K Marie Stolba, Boston: McGraw-Hill, 1998. Supplemental Listening CD –a master recording will be available for listening in the Music Department Office. -

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected]

JAMES D. BABCOCK, MBA, CFA, CPA 191 South Salem Road Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 (203) 994-7244 [email protected] List of Addendums First Addendum – Middle Ages Second Addendum – Modern and Modern Sub-Categories A. 20th Century B. 21st Century C. Modern and High Modern D. Postmodern and Contemporary E. Descrtiption of Categories (alphabetic) and Important Composers Third Addendum – Composers Fourth Addendum – Musical Terms and Concepts 1 First Addendum – Middle Ages A. The Early Medieval Music (500-1150). i. Early chant traditions Chant (or plainsong) is a monophonic sacred form which represents the earliest known music of the Christian Church. The simplest, syllabic chants, in which each syllable is set to one note, were probably intended to be sung by the choir or congregation, while the more florid, melismatic examples (which have many notes to each syllable) were probably performed by soloists. Plainchant melodies (which are sometimes referred to as a “drown,” are characterized by the following: A monophonic texture; For ease of singing, relatively conjunct melodic contour (meaning no large intervals between one note and the next) and a restricted range (no notes too high or too low); and Rhythms based strictly on the articulation of the word being sung (meaning no steady dancelike beats). Chant developed separately in several European centers, the most important being Rome, Hispania, Gaul, Milan and Ireland. Chant was developed to support the regional liturgies used when celebrating Mass. Each area developed its own chant and rules for celebration. In Spain and Portugal, Mozarabic chant was used, showing the influence of North Afgican music. The Mozarabic liturgy survived through Muslim rule, though this was an isolated strand and was later suppressed in an attempt to enforce conformity on the entire liturgy. -

Course Title Credit MUHL M700 Graduate Review of Music History 2 Crs

Course Title Credit MUHL M700 Graduate Review of Music History 2 crs. Fall semester 2004 Instructor Jeannette D. Jones phone 504-813-9334 Communications/Music 204D email [email protected] Office hours: Thurs 4:30-5:30 pm, or by appointment Classes Thursday, 5:30-7:20 pm Graduate Bulletin description According to the results of the entrance test, this course with a B or better is required prior to enrollment in any graduate music history course. It is a one-semester survey of western art music from antiquity to the present and will serve as preparation for graduate music history courses. Prerequisites Graduate standing in music Textbooks and other materials to be purchased by student Mark Evan Bonds, A History of Music in Western Culture (Upper Sadle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003). ________, ed., Anthology of Scores to A History of Music in Western Culture, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, (Upper Sadle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003). ________, ed., Recorded Anthology for A History of Music in Western Culture, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2, (Upper Sadle River, N.J.: Prentice Hall, 2003). Course requirements Required work for this course will include readings from the textbook and other sources, listening, and score study (mostly, but not entirely, from the required anthology). Students will have to take exams, write four short essays, and do other assignments. Special accommodations Students with disabilities are urged to contact the Office of Academic Enrichment and Disability Services as soon as possible so that accommodations can be made. The Office of Disability Services is located on the main campus in the Academic Resource Center, Monroe 405. -

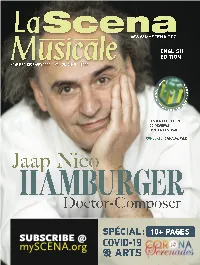

Myscena.Org Sm26-3 EN P02 ADS Classica Sm23-5 BI Pxx 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1

SUBSCRIBE @ mySCENA.org sm26-3_EN_p02_ADS_classica_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:23 AM Page 1 From Beethoven to Bowie encore edition December 12 to 20 2020 indoor 15 concerts festivalclassica.com sm26-3_EN_p03_ADS_Ofra_LMMC_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 1:18 AM Page 1 e/th 129 saison/season 2020 /2021 Automne / Fall BLAKE POULIOT 15 nov. 2020 / Nov.ANNULÉ 15, 2020 violon / violin CANCELLED NEW ORFORD STRING QUARTET 6 déc. 2020 / Dec. 6, 2020 avec / with JAMES EHNES violon et alto / violin and viola CHARLES RICHARD HAMELIN Blake Pouliot James Ehnes Charles Richard Hamelin ©Jeff Fasano ©Benjamin Ealovega ©Elizabeth Delage piano COMPLET SOLD OUT LMMC 1980, rue Sherbrooke O. , Bureau 260 , Montréal H3H 1E8 514 932-6796 www.lmmc.ca [email protected] New Orford String Quartet©Sian Richards sm26-3_EN_p04_ADS_udm_OCM_effendi_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 8:28 AM Page 1 SEASON PRESENTER ORCHESTRE CLASSIQUE DE MONTRÉAL IN THE ABSENCE OF A LIVE CONCERT, GET THE LATEST 2019-2020 ALBUMS QUEBEC PREMIER FROM THE EFFENDI COLLECTION CHAMBER OPERA FOR OPTIMAL HOME LISTENING effendirecords.com NOV 20 & 21, 2020, 7:30 PM RAFAEL ZALDIVAR GENTIANE MG TRIO YVES LÉVEILLÉ HANDEL’S CONSECRATIONS WONDERLAND PHARE MESSIAH DEC 8, 2020, 7:30 PM Online broadcast: $15 SIMON LEGAULT AUGUSTE QUARTET SUPER NOVA 4 LIMINAL SPACES EXALTA CALMA 514 487-5190 | ORCHESTRE.CA THE FACULTY IS HERE FOR YOUR GOALS. musique.umontreal.ca sm26-3_EN_p05_ADS_LSM_subs_sm23-5_BI_pXX 2020-11-03 2:32 PM Page 1 ABONNEZ-VOUS! SUBSCRIBE NOW! Included English Translation Supplément de traduction française inclus -

Philippe De Vitry

METAMORFOSI TRECENTO LA FONTE MUSICA MICHELE PASOTTI MENU TRACKLIST LE MYTHE DE LA TRANSFORMATION DANS L’ARS NOVA PAR MICHAEL SCOTT CUTHBERT METAMORFOSI TRECENTO PAR MICHELE PASOTTI MICHELE PASOTTI & LA FONTE MUSICA BIOS FRANÇAIS / ENGLISH / DEUTSCH TEXTES CHANTÉS MENU METAMORFOSI TRECENTO FRANCESCO LANDINI DA FIRENZE (c.1325-1397) 1 SÌ DOLCE NON SONÒ CHOL LIR’ ORFEO 2’21 PAOLO DA FIRENZE (c.1355-after 1436) 2 NON PIÙ INFELICE 5’51 JACOPO DA BOLOGNA (f.1340-c.1386) 3 FENICE FU’ 2’11 ANONYME (c.1360?) 4 TRE FONTANE (INSTRUMENTALE) 7’15 PHILIPPE DE VITRY (1291-1361) 5 IN NOVA FERT/GARRIT GALLUS/NEUMA 2’49 GUILLAUME DE MACHAUT (c.1300-1377) 6 PHYTON, LE MERVILLEUS SERPENT 4’32 SOLAGE (f.1370-1403) 7 CALEXTONE 4’40 ANTONIO ‘ZACARA’ DA TERAMO (1350/60-after 1413) 8 IE SUY NAVRÉS/GNAFF’A LE GUAGNELE 2’44 4 FILIPPOTTO DA CASERTA (f.2nd half XIVth century) 9 PAR LE GRANT SENZ D’ADRIANE 9’54 MAESTRO PIERO (f.first half XIVth century) 10 SÌ COM’AL CANTO DELLA BELLA YGUANA 4’02 NICCOLÒ DA PERUGIA (f.2nd half XIVth century) 11 QUAL PERSEGUITA DAL SUO SERVO DANNE 4’33 BARTOLINO DA PADOVA (c.1365-1405) 12 STRINÇE LA MAN (INSTRUMENTALE) 1’17 JACOPO DA BOLOGNA 13 NON AL SU’ AMANTE PIÙ DIANA PIACQUE 3’26 MATTEO DA PERUGIA (fl. ca.1400-1416) 14 GIÀ DA RETE D'AMOR 5’02 JACOPO DA BOLOGNA 15 SÌ CHOME AL CHANTO DELLA BELLA YGUANA 3’02 TOTAL TIME: 63’39 5 MENU LA FONTE MUSICA MICHELE PASOTTI MEDIEVAL LUTE & DIRECTION FRANCESCA CASSINARI SOPRANO ALENA DANTCHEVA SOPRANO GIANLUCA FERRARINI TENOR MAURO BORGIONI BARITONE EFIX PULEO FIDDLE TEODORO BAÙ FIDDLE MARCO DOMENICHETTI RECORDER FEDERICA BIANCHI CLAVICYMBALUM MARTA GRAZIOLINO GOTHIC HARP 6 MENU LE MYTHE DE LA TRANSFORMATION DANS L’ARS NOVA PAR MICHAEL SCOTT CUTHBERT Il a fallu une sorcière ayant le pouvoir de transformer les hommes en porcs pour amener Ulysse à perdre tous les autres plaisirs au monde ; mais, pour moi, il suffirait que tu sois mienne pour me faire renoncer à tout autre désir. -

Mus361h1x-201109

MUS 361 Music History, Antiquity through Baroque Instructor: Dr. Aaron I. Hilbun Office Location: 223 Keene Hall Office Hours: by appointment only email: [email protected] Course objectives: To develop a thorough understanding of the stylistic and aesthetic principles of the major periods To understand the historical processes through which musical styles begin, grow, mature and decline To understand major developments in music theory and performance practice To gain familiarity with major composers and literature To gain basic familiarity with non-western and folk music traditions and the impact they have had on western art music To develop the ability to intelligently discuss and write about these subjects Required materials: Mark Evan Bonds, A History of Music in Western Culture, 3rd edition, with accompanying anthology and CDs, $118.50. Recommended materials: Piero Weiss and Richard Taruskin, Music in the Western World, A History in Documents (two copies also on reserve at the Olin Library) Grading: Exams (3 at 15% each) 45% Participation in class discussion 10% Essays (2 at 5% each) 10% Research paper proposal 10% Research paper 25% Exams: There will be three exams, each covering roughly one-third of the semester's course material. They will be non-cumulative, i.e. material from the first part of the semester will not appear on the third exam. Exams will consist of listening excerpts and multiple-choice, short answer, true-false, matching, etc. type questions. There will be no essay questions on the exams. Participation in class discussion: The heart of the learning process in this course will be our class discussions.