A Content Analysis of Infotainment Characteristics in Canadian Newspapers’ Federal Election Coverage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shifting Paradigms

SHIFTING PARADIGMS Report of the Standing Committee on Canadian Heritage Julie Dabrusin, Chair MAY 2019 42nd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Published under the authority of the Speaker of the House of Commons SPEAKER’S PERMISSION The proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees are hereby made available to provide greater public access. The parliamentary privilege of the House of Commons to control the publication and broadcast of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees is nonetheless reserved. All copyrights therein are also reserved. Reproduction of the proceedings of the House of Commons and its Committees, in whole or in part and in any medium, is hereby permitted provided that the reproduction is accurate and is not presented as official. This permission does not extend to reproduction, distribution or use for commercial purpose of financial gain. Reproduction or use outside this permission or without authorization may be treated as copyright infringement in accordance with the Copyright Act. Authorization may be obtained on written application to the Office of the Speaker of the House of Commons. Reproduction in accordance with this permission does not constitute publication under the authority of the House of Commons. The absolute privilege that applies to the proceedings of the House of Commons does not extend to these permitted reproductions. Where a reproduction includes briefs to a Standing Committee of the House of Commons, authorization for reproduction may be required from the authors in accordance with the Copyright Act. Nothing in this permission abrogates or derogates from the privileges, powers, immunities and rights of the House of Commons and its Committees. -

How to Make Use of Data in a Car: Connected Cars, Payment Tech, Analytics, and Other Opportunities

HOW TO MAKE USE OF DATA IN A CAR: CONNECTED CARS, PAYMENT TECH, ANALYTICS, AND OTHER OPPORTUNITIES Andrew Ray David Monteiro May 13, 2020 Tess Blair @MLGlobalTech © 2018 Morgan, Lewis & Bockius LLP Morgan Lewis Automotive Hour Webinar Series Series of automotive industry focused webinars led by members of the Morgan Lewis global automotive team. The 10-part 2020 program is designed to provide a comprehensive overview on a variety of topics related to clients in the automotive industry. Upcoming sessions: JUNE 10 | Employee Benefits in the Automotive and Mobility Context JULY 15 | Working with, or Operating, a Tech Startup in the Automotive and Mobility Sectors AUGUST 5 | Electric Vehicles and Their Energy Impact SEPTEMBER 23 | Autonomous Vehicles Regulation and State Developments NOVEMBER 11 | Environmental Developments and Challenges in the Automotive Space DECEMBER 9 | Capitalizing on Emerging Technology in the Automotive and Mobility Space 2 Table of Contents Section 01 – Introductions Section 02 – Market Overview Section 03 – Data Acquisition and Use Section 04 – Regulatory and Enforcement Risks 3 SECTION 01 INTRODUCTIONS Today’s Presenters Andrew Ray David Monteiro Tess Blair Washington, DC Dallas Philadelphia Tel +1.202.373.6585 Tel +1.214.466.4133 Tel +1.215.963.5161 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] 5 SECTION 02 MARKET OVERVIEW 7 Market Overview • 135 million Americans spend 51 minutes on average commuting to work five days a week. • Connected commerce experience represents a $230 billion market. • Since 2010, investors have poured $20.8 billion into connectivity and infotainment technologies. Source: “2019 Digital Drive Report,” P97 / PYMNTS.com; “Start me up: Where mobility investments are going,” McKinsey & Company. -

Environmental

Back to normal is still a long way off Gwynne Dyer p. 12 What now of the Michael environmental Harris movement in Canada? p.11 Phil Gurski p. 11 Some MPs donating their salary increases to charities p. 4 THIRTY-FIRST YEAR, NO. 1718 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSPAPER MONDAY, APRIL 13, 2020 $5.00 News Remote caucus meetings Analysis Feds’ response Analysis: Did In the time of the pandemic, the feds flip- flop on closing Liberals holding national caucus the border or wearing meetings seven days a week masks amid The Liberals' daily Liberals meetings start with the COVID-19 are using a an update for MPs on new developments outbreak? regular daily and the government's initiatives from BY PETER MAZEREEUW conference Deputy House Leader Kirsty Duncan, he federal government says call for their left, International science and expert advice is Trade Minister Mary T caucus behind its decision to shut the Ng, and Minister border to travellers and its chang- meetings. The of Middle Class ing advice on whether Canadians Prosperity Mona should wear masks amid the CO- Conservatives Fortier. Usually, VID-19 outbreak. While Canada’s a member of the are using top health official pointed to COVID-19 cabinet new science related to using face Zoom and committee, or masks, one expert says there is another cabinet no scientific evidence that could the New minister also joins have informed Canada’s decision them in updating Democrats to close its border on March 16. caucus members. “There is no science about The Hill Times are using whether it works to restrict all photographs by travel into a country,” said Steven GoToMeeting. -

Evidence of the Special Committee on the COVID

43rd PARLIAMENT, 1st SESSION Special Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic EVIDENCE NUMBER 019 Tuesday, June 9, 2020 Chair: The Honourable Anthony Rota 1 Special Committee on the COVID-19 Pandemic Tuesday, June 9, 2020 ● (1200) Mr. Paul Manly (Nanaimo—Ladysmith, GP): Thank you, [Translation] Madam Chair. The Acting Chair (Mrs. Alexandra Mendès (Brossard— It's an honour to present a petition for the residents and con‐ Saint-Lambert, Lib.)): I now call this meeting to order. stituents of Nanaimo—Ladysmith. Welcome to the 19th meeting of the Special Committee on the Yesterday was World Oceans Day. This petition calls upon the COVID-19 Pandemic. House of Commons to establish a permanent ban on crude oil [English] tankers on the west coast of Canada to protect B.C.'s fisheries, tourism, coastal communities and the natural ecosystems forever. I remind all members that in order to avoid issues with sound, members participating in person should not also be connected to the Thank you. video conference. For those of you who are joining via video con‐ ference, I would like to remind you that when speaking you should The Acting Chair (Mrs. Alexandra Mendès): Thank you very be on the same channel as the language you are speaking. much. [Translation] We now go to Mrs. Jansen. As usual, please address your remarks to the chair, and I will re‐ Mrs. Tamara Jansen (Cloverdale—Langley City, CPC): mind everyone that today's proceedings are televised. Thank you, Madam Chair. We will now proceed to ministerial announcements. I'm pleased to rise today to table a petition concerning con‐ [English] science rights for palliative care providers, organizations and all health care professionals. -

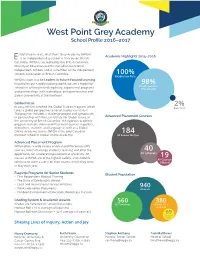

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017

West Point Grey Academy School Profile 2016–2017 stablished in 1996, West Point Grey Academy (WPGA) Academic Highlights 2015–2016 E is an independent day school in Vancouver, British Columbia. WPGA is accredited by the British Columbia Ministry of Education and the Canadian Accredited Independent Schools and is a member of the Independent Schools Association of British Columbia. raduation Rate WPGA’s vision is to be Leaders in Future-Focused Learning. Inspired by our rapidly evolving world, we are a model for ostsecondary schools in offering interdisciplinary, experiential programs lacements and partnerships, with technology, entrepreneurship and global connectivity at the forefront. Global Focus In 2014, WPGA launched the Global Studies Program, which ap ear takes a global perspective to social studies curriculum. The program includes a challenge project and symposium in partnership with the Liu Institute for Global Issues at Advanced Placement Courses the University of British Columbia; the rigorous academic program includes Advanced Placement courses in politics, economics, statistics and language as well as a Global Online Academy course (WPGA is the only Canadian 184 member school in Global Online Academy). A ams ritten Advanced Placement Program WPGA offers a wide variety of Advanced Placement (AP) courses, which challenge students’ learning and offer the 40 opportunity for accelerated placement at university. AP A Scholars classes at WPGA are of the highest calibre, and students continue to score a 4 or 5 on their exams, which they write in May each year. Flagship Programs for Senior Students Student Population • First Responders Medical Training • The Duke of Edinburgh’s Award • Local and International Service Initiatives • Work Experience Placements Students • Outdoor Environmental Education; Wilderness Pursuits Grading System & Academic Awards 560 380 Grades are reflected on school transcripts. -

2013 Annual Report

I AM CHANGE FOR EDUCATION | FOR DISEASE PREVENTION | FOR PEACEFUL COMMUNITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2013 RIGHT TO PLAY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Our Mission is to use sport and play to educate and empower children and youth living in adversity to overcome the effects of poverty, conflict and disease. 92% 95% 85% Of the children in our Of classrooms use Of children in our programs know how active learning— programs would not to prevent HIV from activities and take revenge when sexual transmission discussions—to engage faced with a case of vs 50% of the children children in learning vs peer-initiated conflict. not in our programs. 55% of non-Right To — Results from Benin, Mali Play classrooms. — Results from Uganda and Ghana Evaluation 2011 Evaluation 2009 — Results from Thailand Evaluation 2008 “We believe children are the change makers of the world; all it takes is one child to positively influence their community,” Johann Olav Koss Founder, President & CEO of Right To Play. 1 RIGHTTOPLAY.COM Table of Contents Message From Our CEO 2 At a Glance 3 Where We Work 4 OUR IMPACT 6 Education 8 Health 10 Peace Building 12 We Care, We Do, We Commit 14 We Play, We Are a Team 15 OUR VISION FOR A HEALTHY & SAFE WORLD 16 Sport for Development and Peace 18 Athlete Ambassadors 19 OUR GLOBAL NETWORK 20 Our Partners & Supporters 22 Our National Office: Canada 24 Our National Office: United States of America 26 Our National Office: United Kingdom 28 Our National Office: The Netherlands 30 Our National Office: Norway 32 Our National Office: Switzerland 34 Financial Statements 2013 36 International Board of Directors 40 I am Change RIGHT TO PLAY 2013 ANNUAL REPORT 1 Message From Our CEO What started out as a simple idea has grown into a global movement: using play can teach critical life skills and transform a child’s life. -

HDSB Letter to the Prime Minister Re:Truth and Reconciliation

The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau Prime Minister of Canada The Honourable Doug Ford Premier of Ontario June 29, 2021 Dear Prime Minister Trudeau and Premier Ford, As leaders of a public Board of Education, the Trustees of the Halton District School Board expressed profound anger about the negative and lasting impacts of the residential school system and sadness about the discovery of the horrific loss of life at the Kamloops Residential School for which there must be accountability. As a response, the Trustees of the Halton District School Board adopted the following recommendation unanimously at the June 2, 2021 Regular Meeting of the Board: Be it resolved that the Chair be directed to write a letter on behalf of the Board of Trustees to Prime Minister Trudeau and the Premier of Ontario Ford urging that the Federal and Provincial Governments listen and take action to honour the requests of the Tk'emlúps te Secwépemc First Nations and all Indigenous peoples to fulfil its obligations under the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action. Specifically, the letter should include: ○ That funding be made available by the Government of Canada to undertake and fulfill the Calls to Action regarding Missing Children and Burial Information (#71 - #76). ○ That ground penetrating radar technology be made available to search the grounds of all Residential Schools so that all children can go home. ○ That Indigenous peoples from the communities closest to Residential Schools are actively involved in all stages of the processes at every site. ○ That the voices of the Indigenous community members are centred and lead the process at all sites. -

Political Accountability, Communication and Democracy: a Fictional Mediation?

Türkiye İletişim Araştırmaları Dergisi • Yıl/Year: 2018 • Özel Sayı, ss/pp. e1-e12 • ISSN: 2630-6220 DOI: 10.17829/turcom.429912 Political Accountability, Communication and Democracy: A Fictional Mediation? Siyasal Hesap Verebilirlik, İletişim ve Demokrasi: Medyalaştırılmış bir Kurgu mu? * Ekmel GEÇER 1 Abstract This study, mostly through a critical review, aims to give the description of the accountability in political communication, how it works and how it helps the addressees of the political campaigns to understand and control the politicians. While doing this it will also examine if accountability can help to structure a democratic public participation and control. Benefitting from mostly theoretical and critical debates regarding political public relations and political communication, this article aims (a) to give insights of the ways political elites use to communicate with the voters (b) how they deal with accountability, (c) to learn their methods of propaganda, (d) and how they structure their personal images. The theoretical background at the end suggests that the politicians, particularly in the Turkish context, may sometimes apply artificial (unnatural) communication methods, exaggeration and desire sensational narrative in the media to keep the charisma of the leader and that the accountability and democratic perspective is something to be ignored if the support is increasing. Keywords: Political Communication, Political Public Relations, Media, Democracy, Propaganda, Accountability. Öz Bu çalışma, daha çok eleştirel bir yaklaşımla, siyasal iletişimde hesap verebilirliğin tanımını vermeyi, nasıl işlediğini anlatmayı ve siyasal kampanyaların muhatabı olan seçmenlerin siyasilerin sorumluluğundan ne anladığını ve onu politikacıları kontrol için nasıl kullanmaları gerektiğini anlatmaya çalışmaktadır. Bunu yaparken, hesap verebilirliğin demokratik toplumsal katılımı ve kontrolü inşa edip edemeyeceğini de analiz edecektir. -

Mass Cancellations Put Artists' Livelihoods at Risk; Arts Organizations in Financial Distress

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau March 17, 2020 Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland The Honourable Steven Guilbeault The Honourable William Francis Morneau Minister of Canadian Heritage Minister of Finance The Honourable Mona Fortier The Honourable Navdeep Bains Minister of Middle-Class Prosperity Minister of Innovation, Science and Industry Associate Minister of Finance The Honourable Mélanie Joly Minister of Economic Development and Official Languages Re: Mass cancellations put artists’ livelihoods at risk; arts organizations in financial distress Dear Prime Minister Trudeau; Deputy Prime Minister Freeland; and Ministers Guilbeault, Morneau, Fortier, Joly, and Bains, We write as the leadership of Opera.ca, the national association for opera companies and professionals in Canada. In light of recent developments around COVID-19 and the waves of cancellations as a result of bans on mass gatherings, Opera.ca is urgently requesting federal aid on behalf of the Canadian opera sector and its artists -- its most essential and vulnerable people -- while pledging its own emergency support for artists in desperate need. Opera artists are the heart of the opera sector, and their economic survival is in jeopardy. In response to the dire need captured by a recent survey conducted by Opera.ca, the board of directors of Opera.ca today voted for an Opera Artists Emergency Relief Fund to be funded by the association. Further details will be announced shortly. Of the 14 professional opera companies in Canada, almost all have cancelled their current production and some the remainder of the season. This is an unprecedented crisis with long-reaching implications for the entire Canadian opera sector. -

Debates of the House of Commons

43rd PARLIAMENT, 2nd SESSION House of Commons Debates Official Report (Hansard) Volume 150 No. 092 Friday, April 30, 2021 Speaker: The Honourable Anthony Rota CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 6457 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, April 30, 2021 The House met at 10 a.m. Bibeau Bittle Blaikie Blair Blanchet Blanchette-Joncas Blaney (North Island—Powell River) Blois Boudrias Boulerice Prayer Bratina Brière Brunelle-Duceppe Cannings Carr Casey Chabot Chagger GOVERNMENT ORDERS Champagne Champoux Charbonneau Chen ● (1000) Cormier Dabrusin [English] Damoff Davies DeBellefeuille Desbiens WAYS AND MEANS Desilets Dhaliwal Dhillon Dong MOTION NO. 9 Drouin Dubourg Duclos Duguid Hon. Chrystia Freeland (Minister of Finance, Lib.) moved Duncan (Etobicoke North) Duvall that a ways and means motion to implement certain provisions of Dzerowicz Easter the budget tabled in Parliament on April 19, 2021 and other mea‐ Ehsassi El-Khoury sures be concurred in. Ellis Erskine-Smith Fergus Fillmore The Deputy Speaker: The question is on the motion. Finnigan Fisher Fonseca Fortier If a member of a recognized party present in the House wishes to Fortin Fragiskatos request either a recorded division or that the motion be adopted on Fraser Freeland division, I ask them to rise in their place and indicate it to the Chair. Fry Garneau Garrison Gaudreau The hon. member for Louis-Saint-Laurent. Gazan Gerretsen Gill Gould [Translation] Green Guilbeault Hajdu Hardie Mr. Gérard Deltell: Mr. Speaker, we request a recorded divi‐ Harris Holland sion. Housefather Hughes The Deputy Speaker: Call in the members. Hussen Hutchings Iacono Ien ● (1045) Jaczek Johns Joly Jones [English] Jordan Jowhari (The House divided on the motion, which was agreed to on the Julian Kelloway Khalid Khera following division:) Koutrakis Kusmierczyk (Division No. -

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal Stephen

RIDING MPP CANDIDATE PARTY Ajax Joe Dickson Liberal Stephen Leahy Green Rod Phillips PC Monique Hughes NDP Algoma—Manitoulin Charles Fox Liberal Justin Tilson Green Jib Turner PC Michael Mantha NDP Aurora - Oak Ridges - Richmond Hill Naheed Yaqubian Liberal Stephanie Nicole Duncan Green Michael Parsa PC Katrina Sale NDP Barrie-Innisfil Bonnie North Green Pekka Reinio NDP Andrea Khanjin PC Ann Hoggarth Liberal Barrie-Springwater-Oro-Medonte Keenan Aylwin Green Jeff Kerk Liberal Doug Downey PC Dan Janssen NDP Bay of Quinte Robert Quaiff Liberal Mark Daye Green Todd Smith PC Joanne Belanger NDP Beaches—East York Rima Berns-McGown NDP Arthur Potts Liberal Debra Scott Green Sarah Mallo PC Brampton Centre Safdar Hussain Liberal Laila Zarrabi Yan Green Harjit Jaswal PC Sara Singh NDP Brampton East Dr. Parminder Singh Liberal Raquel Fronte Green Sudeep Verma PC Gurratan Singh NDP Brampton North Harinder Malhi Liberal Pauline Thornham Green Ripudaman Dhillon PC Kevin Yarde NDP Brampton South Sukhwant Thethi Liberal Lindsay Falt Green Prabmeet Sarkaria PC Paramjit Gill NDP Brampton West Vic Dhillon Liberal Julie Guillemet-Ackerman Green Amarjot Sandhu PC Jagroop Singh NDP Brantford - Brant Ruby Toor Liberal Ken Burns Green Will Bouma PC Alex Felsky NDP Bruce—Grey—Owen Sound Elizabeth Marshall Trillium Francesca Dobbyn Liberal Don Marshall Green Karen Gventer NDP Bill Walker PC Burlington Jane McKenna PC Eleanor McMahon Liberal Andrew Drummond NDP Vince Fiorito Green Cambridge Kathryn McGarry Liberal Michele Braniff Green Belinda Karahalios PC Marjorie -

2019 BCSS AGM Package 2!.Pdf

April 26th - 27th, 2019 BCWhistler, SCHOOL British Columbia SPORTS Annual General Meeting Kelowna, British Columbia MEETING PACKAGE 2 April 2019 The Cove Lakeside Resort Kelowna, BC General Information The Cove Lakeside Resort - West Kelowna Hotel Information The Cove Lakeside Resort is located on the western shore of Okanagan Lake. The Resort features elegantly decorated rooms, stunning views and comfortable in-room amenities. If you have booked a room through BCSS, you will have received a confi rmation email from Karen Hum, please check to make sure the reservation information is correct. Things to do in Kelowna • Visit a Winery - Quail’s Gate Winery & Mission Hill Family Estate Winery are a short distance to from the hotel • Visit Bear Creek Provincial Park - A beautiful Provincial Park on the west side of Okanagan Lake • Relax at Lake Okanagan - Can you spot the Ogopogo? • Enjoy a Round of Golf - Test your skills at one of Kelowna’s 19 exceptional courses • Shopping - Kelowna’s downtown shopping core has a blend of retail shops, galleries, and boutiques to explore. Transportation The Cove Lakeside Resort is located at: 4205 Gellatly Road West Kelowna, BC V4T 2K2 Airport Kelowna International Airport has frequent fl ights in and out daily from around the province. It is a short trip from the Airport to the Resort. If you will be fl ying in to the AGM please let us know and we can help with arrangements for transportation to the hotel. Distance to and from the airport is 29km and approximately 25-40 minutes. Kelowna Weather Kelowna’s weather this time of year ranges from: Average Daily High: 15°C Average Daily Low: 3°C Please keep an eye on the weather closer to the AGM, and pack accordingly.