Unlocking Australia's Language Potential: Profiles of 9 Key Languages in Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2012

Board of Trustees Brisbane Grammar School Annual Report 2012 ISSN 1837-8722 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. CONSTITUTION, GOALS AND FUNCTIONS ............................................................. 1 2. LOCATION ...................................................................................................................... 4 3. STRUCTURES ................................................................................................................. 5 4. REVIEW OF THE PROGRESS IN ACHIEVING THE BOARD OF TRUSTEES STATUTORY OBLIGATIONS ....................................................................................... 6 5. SUMMARY OF SIGNIFICANT OPERATIONS ............................................................ 6 6. REVIEW OF PROGRESS TOWARDS ACHIEVING GOALS AND DELIVERING OUTCOMES ................................................................................................................... 16 7. PROPOSED FORWARD OPERATIONS ..................................................................... 19 8. FINANCIAL OPERATIONS AND EFFECTIVENESS ................................................ 20 9. SYSTEMS FOR OBTAINING INFORMATION ABOUT FINANCIAL AND OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE .............................................................................. 21 10. RISK MANAGEMENT .................................................................................................. 22 11. CARERS (RECOGNITION) ACT 2008 ........................................................................ 23 12. PUBLIC SECTOR ETHICS ACT 1994 ........................................................................ -

Answers to Questions on Notice

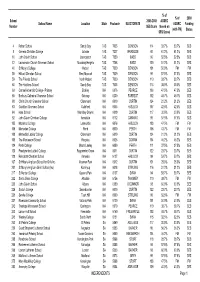

% of % of 2008 School 2005-2008 AGSRC School Name Location State Postcode ELECTORATE AGSRC Funding Number SES Score (based on (with FM) Status SES Score) 4 Fahan School Sandy Bay TAS 7005 DENISON 114 33.7% 33.7% SES 5 Geneva Christian College Latrobe TAS 7307 BRADDON 92 61.2% 61.2% SES 10 John Calvin School Launceston TAS 7250 BASS 99 52.5% 52.5% SES 12 Launceston Church Grammar School Mowbray Heights TAS 7248 BASS 100 51.2% 51.2% SES 40 St Mary's College Hobart TAS 7000 DENISON 101 50.0% FM FM 55 Hilliard Christian School West Moonah TAS 7009 DENISON 95 57.5% 57.5% SES 59 The Friends School North Hobart TAS 7000 DENISON 110 38.7% 38.7% SES 60 The Hutchins School Sandy Bay TAS 7005 DENISON 113 35.0% 35.0% SES 63 Carmel Adventist College - Primary Bickley WA 6076 PEARCE 103 47.5% 47.5% SES 65 Bunbury Cathedral Grammar School Gelorup WA 6230 FORREST 102 48.7% 48.7% SES 68 Christ Church Grammar School Claremont WA 6010 CURTIN 124 21.2% 21.2% SES 83 Guildford Grammar School Guildford WA 6055 HASLUCK 107 42.5% 42.5% SES 84 Hale School Wembley Downs WA 6019 CURTIN 117 30.0% 30.0% SES 92 John Calvin Christian College Armadale WA 6112 CANNING 95 57.5% 57.5% SES 105 Mazenod College Lesmurdie WA 6076 HASLUCK 103 47.5% FM FM 106 Mercedes College Perth WA 6000 PERTH 106 43.7% FM FM 108 Methodist Ladies' College Claremont WA 6010 CURTIN 124 21.2% 21.2% SES 109 The Montessori School Kingsley WA 6026 COWAN 104 46.2% 46.2% SES 124 Perth College Mount Lawley WA 6050 PERTH 111 37.5% 37.5% SES 126 Presbyterian Ladies' College Peppermint Grove WA 6011 CURTIN -

Annual Report 2019

Annual Report 2019 2 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School Interpretation Requests Brisbane Grammar School is committed to providing accessible services to people from all culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds. Please provide any feedback, interpreter requests, copyright requests or suggestions to the Deputy Headmaster – Staff at the undernoted address. Report Availability This report is available for viewing by contacting the Deputy Headmaster – Staff. Brisbane Grammar School Tel (07) 3834 5200 Fax (07) 3834 5202 Email [email protected] Website www.brisbanegrammar.com Online www.brisbanegrammar.com/About/Reporting/ ISSN: 1837-8722 © (Board of Trustees of the Brisbane Grammar School), 2020 Brisbane Grammar School 2019 Annual Report 3 LETTER OF COMPLIANCE 4 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School Table of Contents Letter of Compliance 4 SECTION A GOVERNANCE REPORT 6 About the School 7 Locations 7 Legislative bases 8 Values and ethics 8 Leadership 9 Senior Leadership Team 15 Statutory Requirements 18 Risk management 18 Audit 18 External scrutiny 18 Record keeping 20 SECTION B STRATEGY REPORT 22 From the Chair 23 From the Headmaster 25 Strategic Intent 2018 – 2022 28 2019 In Review 36 Enrolments 36 Academic 39 Student wellbeing 43 Co-Curriculum 46 Staff 49 Advancement and Community Relations 52 Infrastructure 54 Finance 55 SECTION C APPENDICES 57 Open Data 56 Consultancies 58 Overseas travel 58 Financial Statements 59 Glossary 95 Compliance Checklist 99 Brisbane Grammar School 2019 Annual Report 5 Section A Governance Report 6 2019 Annual Report Brisbane Grammar School ABOUT THE SCHOOL Locations Spring Hill Campus Brisbane Grammar School provides education programs on five campuses. The main campus of nearly eight hectares is on Gregory Terrace overlooking the Brisbane CBD and is the site for the delivery of the main academic program across Years 5 to 12, as well as the Indoor Sports Centre and boarding house. -

Players and Administrators

Valley District Cricket Club - Players and Administrators Abercrombie Charles Stuart Born:26 October 1878 in Albury, NSW Bat: Bowl: Died:10 September 1954 in Brisbane Son of David John ABERCROMBIE and Grace Marie CANSDELL. Scools: Brisbane Grammar. He was a bank officer, serving with the Bank of Australasia. 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1902 Acton Geoffrey Brockwell Born:26 December 1970 in Bat: Bowl: Died: in 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1991, 1993, 1995 Adams Brett James Born:28 November 1958 in Townsville Bat:RHB Bowl: WK Died: in Brother of RG Adams He represented Queensland Primary Schools in 1970/71; and Queensland Schoolboys in each season from 1974/75 to 1976/77, being captain in the latter two series. He also played grade cricket for Sandgate-Redcliffe. Schools: Clontarf State; St Pauls, Bald Hills. 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1977, 1981, 1982, 1983 Adams Ross George Born:16 November 1955 in Bat: Bowl: RFM Died: in Brother of BJ Adams. Previously played for Northern Suburbs. 1st Grade Career: (season commencing) 1983 Adamson Charles Young Born:18 April 1875 in Neville’s Cross, Durham, England Bat:RHB Bowl: LSM Died:17 September 1918 in Salonica, Greece Son of Annie LODGE and John ADAMSON. His father and sons CL and JA Adamson all played Minor County cricket for Durham. His brother-in-law to Lewis Vaughan Lodge, who played international football for England He played Minor Country cricket in England for Durham from 1894 to 1914. He was also a rugby player representing Durham and England and touring Australia in 1899. -

Newsletter Week 1 Term 4 Friday 11 October 2019

Newsletter Week 1 Term 4 Friday 11 October 2019 BGS Parent and Son Kokoda Trek | September Holidays In this issue BGSState Newsletter Tennis Tournament| Lead Article Teacher Recognised Duke of Edinburgh Award Headmaster Anthony Micallef Welcome to Term 4 I would like to welcome the BGS community to Term 4. I trust everyone had a satisfying break in preparation for this important term. Throughout the holidays, many students actively prepared for the academic and co-curricular rigours of Term 4. The BGS Track and Field boys prepared for their season with a holiday training camp, while others started pre- season training ahead of Term 1 2020. Students also embarked on their Public Purpose expeditions in Cambodia and Kokoda. Thank you to all staff and students who participated in these activities over the break. Your commitment to the School is appreciated. Working together to achieve a common goal is the essence of being human – it is knowing and feeling that you belong to something special. As we start Term 4, I congratulate the student body for rounding out Term 3 admirably. The boys maintained decorum and behaved respectfully while completing assessments and co-curricular responsibilities to high standards. I also thank the Year 12 cohort for conducting themselves appropriately at the formal. The Class of 2019 was in good spirits and gentlemanly in their manner. I hope the boys have returned from their holiday well rested and ready for a relatively short and constructive term. It is important for every student to see this term as a down payment on further academic success rather than a slide into holidays. -

A History of German-Scandinavian Relations

A History of German – Scandinavian Relations A History of German-Scandinavian Relations By Raimund Wolfert A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Raimund Wolfert 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations Table of contents 1. The Rise and Fall of the Hanseatic League.............................................................5 2. The Thirty Years’ War............................................................................................11 3. Prussia en route to becoming a Great Power........................................................15 4. After the Napoleonic Wars.....................................................................................18 5. The German Empire..............................................................................................23 6. The Interwar Period...............................................................................................29 7. The Aftermath of War............................................................................................33 First version 12/2006 2 A History of German – Scandinavian Relations This essay contemplates the history of German-Scandinavian relations from the Hanseatic period through to the present day, focussing upon the Berlin- Brandenburg region and the northeastern part of Germany that lies to the south of the Baltic Sea. A geographic area whose topography has been shaped by the great Scandinavian glacier of the Vistula ice age from 20000 BC to 13 000 BC will thus be reflected upon. According to the linguistic usage of the term -

Evidence Exchange 2016

[email protected] | evidenceforlearning.org.au | @E4Ltweets Evidence Exchange 2016 SPEAKERS Anthony Mackay AM Chief Executive Officer, Centre for Strategic Education (CSE) Anthony Mackay AM is CEO, Centre for Strategic Education (CSE) Melbourne, Inaugural Chair, Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL), and Inaugural Deputy Chair, Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA). Tony is CoChair of the Global Education Leaders Partnership (GELP) and Inaugural Chair of the Innovation Unit Ltd, England. He is Consultant Advisor to OECD/CERI. Tony is a founding member of the Governing Council of the National College for School Leadership in England. Tony is a member of the International Advisory Board for the Centre for International Benchmarking NCEE, Washington DC. Tony is an Honorary Fellow in the Graduate School of Education at the University of Melbourne, a Council Member of Swinburne University of Technology, a Board Director of the Australian Council for Educational Research, the Asia Education Foundation, the Foundation for Young Australians, and Teach for Australia. Cath Apanah Assistant Principal, Montrose Bay High (TAS) Cath is a passionate advocate for public education and is driven to improve both staff and student learning. She is currently the Assistant Principal for Raising the Bar at Montrose Bay High in Hobart, Tasmania where she is responsible for improving literacy outcomes for students. Cath and the Literacy Team have used data to inform a whole school focus on writing through the development and implementation of a Write to Learn program. The program has worked to build the capacity of staff to plan for and deliver targeted teaching strategies. -

Grammar School Magazine

Vol. IX. NOVEMBER, 1907. No. 27- BRISANE GRAMMAR SCHOOL MAGAZINE. lrtakrnr: OUTRIDGE PKINTING CO., LTID. .j9 yIEN STREET'. S907. OUTRIDGE PRINTINO 00. Ltd. Priaters, Bookbiders, Statioersn meet Maebleery. ittee e phi. | l Itee. ulin. PtentBoxes. Foldin c c, and are costantly adin. to thea '11 f3i8 QUEEN ST., BRISBANE. NNMiru hWit FHS|m Plan see ftdll Ad wrtiuments. Morrows Limited, WNII I III~lII "__ .. Confectioners IPee S**., @.emes. a •-**'"---. )Biscuit Baker s, lube.. ParNee. eII. k -: >; +- . -sada" s e. ,..BISBANE. Igamee I. e S111.Y0SB ~s b m~ Agst GeVin a. km v el IAs. hobe ahaed - a Branch Fa~corle: Towvilke and Sydney. -~ A. HERGA, tbronaomcer, Ulatcb, ain Clock fUllaer. Chronographs, Repeaters, Perpetual Calendars a Speciality. Chronometers kept Rated. Importer of btandard Harometers and Electric Clocks. Correct Time daily by electric signals from the Observatory, by permission of the surveyor-General. eIII.Uee IWat m .. .. 11 '- V1eens' sa esMe's Sdve, Webes .. Ut 1/-, 48 II-, 14/-t Ladies' OeM Levere WShes .... 1 1/ M8 II/- WAKEFIELD'S BUILDINGS. EDWARD STREFT. 4 .4 dvertiserments. 'Waton, erguson 6eo. f J rters ofo 6 ceha and Sttrionery, Qoa h.t, " a.-----. \'. F. & Co. toc'k all Ei.1ucational \\,rk used in Private, State and (ramnmar Schools and also all iooks used in connection with the Sydney (University Exain;ations and supply them at special prices to pupils. MURRBL &BBEKER 90 QUEEN STREET NEXT IPAIIN ' MI AN I'ACTUL HEiS Ladis' Ha& Cariers lr Home auld Travel. 89o asnd 40/-. NONE BUT THE B11'f ISADDLRY AiD LARNESS f every deulptlion. -

"Ich Höre Gern Diesen Dialekt, Erinnert Mich an Meine Urlaube in Kärnten

"Ich höre gern diesen Dialekt, erinnert mich an meine Urlaube in Kärnten ... ": A survey of the usage and the popularity of Austrian dialects in Vienna John Bellamy (Manchester) A survey of over 200 Austrians was undertaken in Vienna to investigate the extent to which they say they use dialect. They were asked if they speak dialect and if they do, in which situations they would switch to using predominantly Hochsprache. The responses have been analysed according to age, gender, birthplace (in Austria) and occupation to find out if the data reveals underlying correlations, especially to see if there have been any developments of note since earlier studies (for example, Steinegger 1995). The same group of informants were also asked about their opinions of Austrian dialects in general and this paper details their answers along with the reasons behind their positive or negative responses in this regard. The data collected during this survey will be compared to other contemporary investigations (particularly Soukup 2009) in an effort to obtain a broader view of dialect usage and attitudes towards dialect in Vienna and its environs. Since a very similar study was undertaken at the same time in the UK (Manchester) with more or less the same questions, the opportunity presents itself to compare dialect usage in the area in and around Vienna with regional accents and usage in the urban area of Manchester. References will be made during the course of the presentation to both sets of data. Language planning in Europe during the long 19th century: The selection of the standard language in Norway and Flanders Els Belsack (VU Brussel) The long 19th century (1794-1914) is considered to be the century of language planning par excellence. -

Helmut Rainer Kussler

Helmut Rainer Kussler 1. PERSONAL INFORMATION Date of birth 3 November 1943 Nationality German (South African permanent resident) Marital status Married, one daughter Position Emeritus Professor of German Department of Modern Foreign Languages [until 1997: Department of German], University of Stellenbosch / South Africa Language Proficiency German (mother tongue), Afrikaans and English (second languages); publi- cations in all three languages Computing Skills Professional level in multimedia language learning courseware imple- mentation and development Contact information P.O. Box 3530, Matieland 7602 South Africa Tel [x27] (0)21 886 6327 Email [email protected] Fax [x27] 886 166 186 2. STUDY, TRAINING AND EMPLOYMENT Study University of Stellenbosch, South Africa: 1963-1969: B.A. 1965 [Majors: German with distinction, Latin; Sub Majors: Afrikaans- Dutch, English, History] Hons.-B.A. in German cum laude (grade: 100%): 1966 2 M.A. in German cum laude (grade: 100%): 1967 TITLE OF THESIS: Konzeption und Gestaltung des Abschieds in der modernen deutschen Lyrik. Untersuchungen zu Gedichten von Nietzsche, Rilke, Benn und Ingeborg Bachmann Doctor Litterarum (D.Litt.) in German: 1969 (Doctoral dissertations are not graded at Stellenbosch University) TITLE OF DISSERTATION: Das Abschiedsmotiv in der deutschen Lyrik des 20. Jahrhunderts Post-doctoral Study and Training Full time study at the University of Hamburg (two terms: 1971/72) COURSES COMPLETED (certified): Einführung in das Studium der deutschen Literatur (Prof. Dr. Gunther Martens) Lyrik der DDR (Dr. Paul Kersten) Formen der uneigentlichen Rede (Dr. Werner Eggers) Deutsche Literatur 1895-1910 (Dr. Werner Eggers) Lyrik des 17. Jahrhunderts (Dr. Carl-Alfred Zell) Das Lehrgedicht (Dr. Carl-Alfred Zell) Training in suggestopedic language instruction: 1983: One-week workshop, Iowa State University/USA (Dr. -

The Married Woman, the Teaching Profession and the State in Victoria, 1872-1956

THE MARRIED WOMAN, THE TEACHING PROFESSION AND THE STATE IN VICTORIA, 1872-1956 Donna Dwyer B.A., Dip. Ed. (Monash), Dip. Crim., M.Ed. (Melb.) Submitted in fulfilmentof the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Educafion at The University of Melbourne 2002 , . Abstract This thesis is a study of married women's teaching labour in the Victorian Education Department. It looks at the rise to power of married women teachers, the teaching matriarchs. in the 1850s and 1860s in early colonial Victoria when married women teachers were valued for the moral propriety their presence brought to the teaching of female pupils. In 1872 the newly created Victorian Education Department would herald a new regime and the findings of the Rogers Templeton Commission spell doom for married women teachers. The thesis traces their expulsion from the service under the 1889 Public Service Act implementing the marriage bar. The labyrinthine legislation that followed the passing of the Public Service Act 1889 defies adequate explanation but the outcome was clear. For the next sixty-seven years the bar would remain in place, condemning the 'needy' married woman teacher to life as an itinerant temporary teacher at the mercy of the Department. The irony was that this sometimes took place under 'liberal' administrators renowned for their reformist policies. When married women teachers returned in considerable numbers during the Second World War, they were supported in their claim for reinstatement by women unionists in the Victorian Teachers' Union (VTU). In the 1950s married women temporary teachers, members of the VTU, took up the fight, forming the Temporary Teachers' Club (TIC) to press home their claims. -

Building an Education System for a Modern Australia

THE McKell Institute Insti tute McKell THE MCKELLTHE INSTITUTE No Mind Left Behind Building an education system for a modern Australia OCTOBER 2016 t About the McKell Institute The1. McKellIntroduction Institute is an independent, not-for-profit, public policy institute dedicated to developing practical policy ideas and contributing to public debate. The McKell Institute takes its name from New South Wales’ wartime Premier and Governor-General of Australia, William McKell. William McKell made a powerful contribution to both New South Wales and Australian society through significant social, economic and environmental reforms. For more information phone (02) 9113 0944 or visit www.mckellinstitute.org.au About the Author Acknowledgments MARIEKE D’CRUZ The author would like to thank the following people for their valuable feedback and contributions Marieke is a during the construction of this report. member of the PROFESSOR ANTHONY WELCH: Anthony Welch is McKell Institute’s a Professor of Education at the University of Sydney policy team and specialising in national and international education policy. has contributed to a wide range of PROFESSOR ANNE DALY: Anne Daly is a Professor of research since 2014. Economics at the University of Canberra and a fellow at the National Centre for Social and Economic Modelling She holds a (NATSEM). Bachelor of Arts DR GILLIAN CONSIDINE: Gillian Considine has over 15 with a double-major in International years experience as an education and social researcher Politics and Media and Communications within both universities and not-for-profits. from the University of Melbourne, and is BRIAN EASTAUGHFFE: Brian Eastaughffe is the Principal currently completing a Master of Public of Carmel College in Queensland and has three decades Policy at the University of Sydney.