Federal Guidance Report No. 11: Limiting Values Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Personal Radiation Monitoring

Personal Radiation Monitoring Tim Finney 2020 Radiation monitoring Curtin staff and students who work with x-ray machines, neutron generators, or radioactive substances are monitored for exposure to ionising radiation. The objective of radiation monitoring is to ensure that existing safety procedures keep radiation exposure As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA). Personal radiation monitoring badges Radiation exposure is measured using personal radiation monitoring badges. Badges contain a substance that registers how much radiation has been received. Here is the process by which a user’s radiation dose is measured: 1. The user is given a badge to wear 2. The user wears the badge for a set time period (usually three months) 3. At the end of the set time, the user returns the badge 4. The badge is sent away to be read 5. A dose report is issued. These steps are repeated until monitoring is no longer required. Badges are supplied by a personal radiation monitoring service provider. Curtin uses a service provider named Landauer. In addition to user badges, the service provider sends control badges that are kept on site in a safe place away from radiation sources. The service provider reads each badge using a process that extracts a signal from the substance contained in the badge to obtain a dose measurement. (Optically stimulated luminescence is one such process.) The dose received by the control badge is subtracted from the user badge reading to obtain the user dose during the monitoring period. Version 1.0 Uncontrolled document when printed Health and Safety Page 1 of 7 A personal radiation monitoring badge Important Radiation monitoring badges do not protect you from radiation exposure. -

Chapter 1.2: Transformation Kinetics

Chapter 1: Radioactivity Chapter 1.2: Transformation Kinetics 200 NPRE 441, Principles of Radiation Protection Chapter 1: Radioactivity http://www.world‐nuclear.org/info/inf30.html 201 NPRE 441, Principles of Radiation Protection Chapter 1: Radioactivity Serial Transformation In many situations, the parent nuclides produce one or more radioactive offsprings in a chain. In such cases, it is important to consider the radioactivity from both the parent and the daughter nuclides as a function of time. • Due to their short half lives, 90Kr and 90Rb will be completely transformed, results in a rapid building up of 90Sr. • 90Y has a much shorter half‐life compared to 90Sr. After a certain period of time, the instantaneous amount of 90Sr transformed per unit time will be equal to that of 90Y. •Inthiscase,90Y is said to be in a secular equilibrium. 202 NPRE 441, Principles of Radiation Protection Chapter 1: Radioactivity Exponential DecayTransformation Kinetics • Different isotopes are characterized by their different rate of transformation (decay). • The activity of a pure radionuclide decreases exponentially with time. For a given sample, the number of decays within a unit time window around a given time t is a Poisson random variable, whose expectation is given by t Q Q0e •Thedecayconstant is the probability of a nucleus of the isotope undergoing a decay within a unit period of time. 203 NPRE 441, Principles of Radiation Protection Chapter 1: Radioactivity Why Exponential Decay? The decay rate, A, is given by Separate variables in above equation, we have The decay constant is the probability of a nucleus of the isotope undergoing a decay within a unit period of time. -

Experimental Γ Ray Spectroscopy and Investigations of Environmental Radioactivity

Experimental γ Ray Spectroscopy and Investigations of Environmental Radioactivity BY RANDOLPH S. PETERSON 216 α Po 84 10.64h. 212 Pb 1- 415 82 0- 239 β- 01- 0 60.6m 212 1+ 1630 Bi 2+ 1513 83 α β- 2+ 787 304ns 0+ 0 212 α Po 84 Experimental γ Ray Spectroscopy and Investigations of Environmental Radioactivity Randolph S. Peterson Physics Department The University of the South Sewanee, Tennessee Published by Spectrum Techniques All Rights Reserved Copyright 1996 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Introduction ....................................................................................................................4 Basic Gamma Spectroscopy 1. Energy Calibration ................................................................................................... 7 2. Gamma Spectra from Common Commercial Sources ........................................ 10 3. Detector Energy Resolution .................................................................................. 12 Interaction of Radiation with Matter 4. Compton Scattering............................................................................................... 14 5. Pair Production and Annihilation ........................................................................ 17 6. Absorption of Gammas by Materials ..................................................................... 19 7. X Rays ..................................................................................................................... 21 Radioactive Decay 8. Multichannel Scaling and Half-life ..................................................................... -

Proper Use of Radiation Dose Metric Tracking for Patients Undergoing Medical Imaging Exams

Proper Use of Radiation Dose Metric Tracking for Patients Undergoing Medical Imaging Exams Frequently Asked Questions Introduction In August of 2021, the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM), the American College of Radiology (ACR), and the Health Physics Society (HPS) jointly released the following position statement advising against using information about a patient’s previous cumulative dose information from medical imaging exams to decide the appropriateness of future imaging exams. This statement was also endorsed by the Radiological Society of North America (RSNA). It is the position of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine (AAPM), the American College of Radiology (ACR), and the Health Physics Society (HPS) that the decision to perform a medical imaging exam should be based on clinical grounds, including the information available from prior imaging results, and not on the dose from prior imaging-related radiation exposures. AAPM has long advised, as recommended by the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), that justification of potential patient benefit and subsequent optimization of medical imaging exposures are the most appropriate actions to take to protect patients from unnecessary medical exposures. This is consistent with the foundational principles of radiation protection in medicine, namely that patient radiation dose limits are inappropriate for medical imaging exposures. Therefore, the AAPM recommends against using dose values, including effective dose, from a patient’s prior imaging exams for the purposes of medical decision making. Using quantities such as cumulative effective dose may, unintentionally or by institutional or regulatory policy, negatively impact medical decisions and patient care. This position statement applies to the use of metrics to longitudinally track a patient’s dose from medical radiation exposures and infer potential stochastic risk from them. -

Nuclide Safety Data Sheet Iron-59

59 Nuclide Safety Data Sheet 59 Iron-59 Fe www.nchps.org Fe I. PHYSICAL DATA 1 Gammas/X-rays: 192 keV (3% abundance); 1099 keV (56%), 1292 keV (44%) Radiation: 1 Betas: 131 keV (1%), 273 keV (46%), 466 keV (53%) 2 Gamma Constant: 0.703 mR/hr per mCi @ 1.0 meter [1.789E-4 mSv/hr per MBq @ 1.0 meter] 1 Half-Life [T½] : Physical T½: 44.5 day 3 Biological T½: ~1.7 days (ingestion) ; much longer for small fraction Effective T½: ~1.7 days (varies; also small fraction retained much longer) Specific Activity: 4.97E5 Ci/g [1.84E15 Bq/g] max.1 II. RADIOLOGICAL DATA Radiotoxicity4: 1.8E-9 Sv/Bq (67 mrem/uCi) of 59Fe ingested [CEDE] 4.0E-9 Sv/Bq (150 mrem/uCi) of 59Fe inhaled [CEDE] Critical Organ: Spleen1, [blood] Intake Routes: Ingestion, inhalation, puncture, wound, skin contamination (absorption); Radiological Hazard: Internal Exposure; Contamination III. SHIELDING Half Value Layer [HVL] Tenth Value Layer [TVL] Lead [Pb] 15 mm (0.59 inches) 45 mm (1.8 inches) Steel 35 mm (1.4 inches) 91 mm (3.6 inches) The accessible dose rate should be background but must be < 2 mR/hr IV. DOSIMETRY MONITORING - Always wear radiation dosimetry monitoring badges [body & ring] whenever handling 59Fe V. DETECTION & MEASUREMENT Portable Survey Meters: Geiger-Mueller [e.g. PGM] to assess shielding effectiveness & contamination Wipe Test: Liquid Scintillation Counter, Gamma Counter VI. SPECIAL PRECAUTIONS • Avoid skin contamination [absorption], ingestion, inhalation, & injection [all routes of intake] • Use shielding (lead) to minimize exposure while handling of 59Fe • Use tools (e.g. -

General Guidelines for the Estimation of Committed Effective Dose from Incorporation Monitoring Data

Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaftt Wissenschaftliche Berichte FZKA 7243 General Guidelines for the Estimation of Committed Effective Dose from Incorporation Monitoring Data (Project IDEAS – EU Contract No. FIKR-CT2001-00160) H. Doerfel, A. Andrasi, M. Bailey, V. Berkovski, E. Blanchardon, C.-M. Castellani, C. Hurtgen, B. LeGuen, I. Malatova, J. Marsh, J. Stather Hauptabteilung Sicherheit August 2006 Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe in der Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft Wissenschaftliche Berichte FZKA 7243 GENERAL GUIDELINES FOR THE ESTIMATION OF COMMITTED EFFECTIVE DOSE FROM INCORPORATION MONITORING DATA (Project IDEAS – EU Contract No. FIKR-CT2001-00160) H. Doerfel, A. Andrasi 1, M. Bailey 2, V. Berkovski 3, E. Blanchardon 6, C.-M. Castellani 4, C. Hurtgen 5, B. LeGuen 7, I. Malatova 8, J. Marsh 2, J. Stather 2 Hauptabteilung Sicherheit 1 KFKI Atomic Energy Research Institute, Budapest, Hungary 2 Health Protection Agency, Radiation Protection Division, (formerly National Radiological Protection Board), Chilton, Didcot, United Kingdom 3 Radiation Protection Institute, Kiev, Ukraine 4 ENEA Institute for Radiation Protection, Bologna, Italy 5 Belgian Nuclear Research Centre, Mol, Belgium 7 Institut de Radioprotection et de Sûreté Nucléaire, Fontenay-aux-Roses, France 8 Electricité de France (EDF), Saint-Denis, France 9 National Radiation Protection Institute, Praha, Czech Republic Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH, Karlsruhe 2006 Für diesen Bericht behalten wir uns alle Rechte vor Forschungszentrum Karlsruhe GmbH Postfach 3640, 76021 Karlsruhe Mitglied der Hermann von Helmholtz-Gemeinschaft Deutscher Forschungszentren (HGF) ISSN 0947-8620 urn:nbn:de:0005-072434 IDEAS General Guidelines – June 2006 Abstract Doses from intakes of radionuclides cannot be measured but must be assessed from monitoring, such as whole body counting or urinary excretion measurements. -

Cumulative Radiation Dose in Patients Admitted with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: a Prospective PATIENT SAFETY Study Using a Self-Developing Film Badge

Cumulative Radiation Dose in Patients Admitted with Subarachnoid Hemorrhage: A Prospective PATIENT SAFETY Study Using a Self-Developing Film Badge A.C. Mamourian BACKGROUND AND PURPOSE: While considerable attention has been directed to reducing the x-ray H. Young dose of individual imaging studies, there is little information available on the cumulative dose during imaging-intensive hospitalizations. We used a radiation-sensitive badge on 12 patients admitted with M.F. Stiefel SAH to determine if this approach was feasible and to measure the extent of their x-ray exposure. MATERIALS AND METHODS: After obtaining informed consent, we assigned a badge to each of 12 patients and used it for all brain imaging studies during their ICU stay. Cumulative dose was deter- mined by quantifying exposure on the badge and correlating it with the number and type of examinations. RESULTS: The average skin dose for the 3 patients who had only diagnostic DSA without endovascular intervention was 0.4 Gy (0.2–0.6 Gy). The average skin dose of the 8 patients who had both diagnostic DSA and interventions (eg, intra-arterial treatment of vasospasm and coiling of aneurysms) was 0.9 Gy (1.8–0.4 Gy). One patient had only CT examinations. There was no effort made to include or exclude the badge in the working view during interventions. CONCLUSIONS: It is feasible to incorporate a film badge that uses a visual scale to monitor the x-ray dose into the care of hospitalized patients. Cumulative skin doses in excess of 1 Gy were not uncommon (3/12) in this group of patients with acute SAH. -

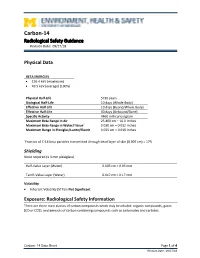

Carbon-14 Radiological Safety Guidance Revision Date: 09/27/18

Carbon-14 Radiological Safety Guidance Revision Date: 09/27/18 Physical Data BETA ENERGIES • 156.4 keV (maximum) • 49.5 keV (average) (100%) Physical Half-Life 5730 years Biological Half-Life 10 days (Whole Body) Effective Half-Life 10 days (Bound/Whole Body) Effective Half-Life 40 days (Unbound/Bone) Specific Activity 4460 millicuries/gram Maximum Beta Range in Air 25.400 cm = 10.0 inches Maximum Beta Range in Water/Tissue* 0.030 cm = 0.012 inches Maximum Range in Plexiglas/Lucite/Plastic 0.025 cm = 0.010 inches *Fraction of C-14 beta particles transmitted through dead layer of skin (0.007 cm) = 17% Shielding None required (≤ 3 mm plexiglass) Half-Value Layer (Water) 0.005 cm = 0.05 mm Tenth-Value Layer (Water) 0.017 cm = 0.17 mm Volatility • Inherent Volatility (STP) is Not Significant Exposure: Radiological Safety Information There are three main classes of carbon compounds which may be inhaled: organic compounds, gases (CO or CO2), and aerosols of carbon containing compounds such as carbonates and carbides. Carbon- 14 Data Sheet Page 1 of 4 Revision Date: 09/27/18 Exposure Rates Dose Rate from a 1.0 millicurie isotropic point source of C-14: DISTANCE RAD/HOUR 1.0 cm 1241.4 2.0 cm 250.4 15.2 cm 0.126 20.0 cm 0.0046 Exposure Prevention • Always wear a lab coat and disposable gloves when working with C-14. • Possibility of organic C-14 compounds being absorbed through gloves. Administrative Controls • Care should be taken not to generate CO2 gas that could be inhaled. -

Radiation Glossary

Radiation Glossary Activity The rate of disintegration (transformation) or decay of radioactive material. The units of activity are Curie (Ci) and the Becquerel (Bq). Agreement State Any state with which the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission has entered into an effective agreement under subsection 274b. of the Atomic Energy Act of 1954, as amended. Under the agreement, the state regulates the use of by-product, source, and small quantities of special nuclear material within said state. Airborne Radioactive Material Radioactive material dispersed in the air in the form of dusts, fumes, particulates, mists, vapors, or gases. ALARA Acronym for "As Low As Reasonably Achievable". Making every reasonable effort to maintain exposures to ionizing radiation as far below the dose limits as practical, consistent with the purpose for which the licensed activity is undertaken. It takes into account the state of technology, the economics of improvements in relation to state of technology, the economics of improvements in relation to benefits to the public health and safety, societal and socioeconomic considerations, and in relation to utilization of radioactive materials and licensed materials in the public interest. Alpha Particle A positively charged particle ejected spontaneously from the nuclei of some radioactive elements. It is identical to a helium nucleus, with a mass number of 4 and a charge of +2. Annual Limit on Intake (ALI) Annual intake of a given radionuclide by "Reference Man" which would result in either a committed effective dose equivalent of 5 rems or a committed dose equivalent of 50 rems to an organ or tissue. Attenuation The process by which radiation is reduced in intensity when passing through some material. -

``Low Dose``And/Or``High Dose``In Radiation Protection: a Need To

IAEA-CN-67/154 "LOW DOSE" AND/OR "HIGH DOSE" IN RADIATION PROTECTION: A NEED TO SETTING CRITERIA FOR DOSE CLASSIFICATION Mehdi Sohrabi National Radiation Protection Department & XA9745670 Center for Research on Elevated Natural Radiation Atomic Energy Organization of Iran, Tehran ABSTRACT The "low dose" and/or "high dose" of ionizing radiation are common terms widely used in radiation applications, radiation protection and radiobiology, and natural radiation environment. Reading the title, the papers of this interesting and highly important conference and the related literature, one can simply raise the question; "What are the levels and/or criteria for defining a low dose or a high dose of ionizing radiation?". This is due to the fact that the criteria for these terms and for dose levels between these two extreme quantities have not yet been set, so that the terms relatively lower doses or higher doses are usually applied. Therefore, setting criteria for classification of radiation doses in the above mentioned areas seems a vital need. The author while realizing the existing problems to achieve this important task, has made efforts in this paper to justify this need and has proposed some criteria, in particular for the classification of natural radiation areas, based on a system of dose limitation. In radiation applications, a "low dose" is commonly associated to applications delivering a dose such as given to a patient in a medical diagnosis and a "high dose" is referred to a dose in applications such as radiotherapy, mutation breeding, control of sprouting, control of insects, delay ripening, and sterilization having a range of doses from 1 to 105 Gy, for which the term "high dose dosimetry" is applied [1]. -

General Chapter <821> Radioactivity

BRIEFING 821 Radioactivity, USP 38 page 616. This chapter was introduced in its current form in 1975 and has not undergone any major revision since its first publication. Currently, ⟨the chapter⟩ contains definitions, special considerations, and procedures with respect to the monographs for radiopharmaceuticals (radioactive drugs). The majority of this chapter is informational. USP has launched an initiative to minimize nonprocedural information in general chapters with numbers below 1000. The USP Council of Experts believes that 821 should be revised as part of this initiative. To achieve this objective, several members of the USP Council of Experts jointly published a Stimuli article in PF 38(4) [July–Aug.⟨ 2012],⟩ Revision of General Chapter Radioactivity 821 . The objectives of this Stimuli article were threefold: (1) provide background information about the need for the proposed revision, (2) initiate discussion about this topic, and⟨ (3)⟩ solicit public comments for review and discussion by the relevant Expert Committee and Expert Panel members and USP staff. The current chapter is divided into two major sections, General Considerations and Identification and Assay of Radionuclides, both of which contain several subsections with information about aspects of radioactivity. Because of the nature of the information presented in these subsections, these can be moved to the proposed Radioactivity— Theory and Practice 1821 . The Terms and Definitions section is now listed as Glossary and has been revised to reflect current practices. The revised chapter will contain procedures and⟨ information⟩ about instrumentation used in the identification and assay of the radionuclides, along with appropriate information about calibration and maintenance of instrumentation. -

Internal and External Exposure Exposure Routes 2.1

Exposure Routes Internal and External Exposure Exposure Routes 2.1 External exposure Internal exposure Body surface From outer space contamination and the sun Inhalation Suspended matters Food and drink consumption From a radiation Lungs generator Radio‐ pharmaceuticals Wound Buildings Ground Radiation coming from outside the body Radiation emitted within the body Radioactive The body is equally exposed to radiation in both cases. materials "Radiation exposure" refers to the situation where the body is in the presence of radiation. There are two types of radiation exposure, "internal exposure" and "external exposure." External exposure means to receive radiation that comes from radioactive materials existing on the ground, suspended in the air, or attached to clothes or the surface of the body (p.25 of Vol. 1, "External Exposure and Skin"). Conversely, internal exposure is caused (i) when a person has a meal and takes in radioactive materials in the food or drink (ingestion); (ii) when a person breathes in radioactive materials in the air (inhalation); (iii) when radioactive materials are absorbed through the skin (percutaneous absorption); (iv) when radioactive materials enter the body from a wound (wound contamination); and (v) when radiopharmaceuticals containing radioactive materials are administered for the purpose of medical treatment. Once radioactive materials enter the body, the body will continue to be exposed to radiation until the radioactive materials are excreted in the urine or feces (biological half-life) or as the radioactivity weakens over time (p.26 of Vol. 1, "Internal Exposure"). The difference between internal exposure and external exposure lies in whether the source that emits radiation is inside or outside the body.