Mise En Place: Setting the Stage for Thought and Action

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 April 1875

WALLACE, (Richard Horatio) Edgar Geboren: Greenwich, Londen, 1 april 1875. Overleden: Hollywood, USA, 10 februari 1932 Opleiding: St. Peter's School, Londen; kostschool, Camberwell, Londen, tot 12 jarige leeftijd. Carrière: Wallace was de onwettige zoon van een acteur, werd geadopteerd door een viskruier en ging op 12-jarige leeftijd van huis weg; werkte bij een drukkerij, in een schoen- winkel, rubberfabriek, als zeeman, stukadoor, melkbezorger, in Londen, 1886-1891; corres- pondent, Reuter's, Zuid Afrika, 1899-1902; correspondent, Zuid Afrika, London Daily Mail, 1900-1902 redacteur, Rand Daily News, Johannesburg, 1902-1903; keerde naar Londen terug: journalist, Daily Mail, 1903-1907 en Standard, 1910; redacteur paardenraces en later redacteur The Week-End, The Week-End Racing Supplement, 1910-1912; redacteur paardenraces en speciaal journalist, Evening News, 1910-1912; oprichter van de bladen voor paardenraces Bibury's Weekly en R.E. Walton's Weekly, redacteur, Ideas en The Story Journal, 1913; schrijver en later redacteur, Town Topics, 1913-1916; schreef regelmatig bijdragen voor de Birmingham Post, Thomson's Weekly News, Dundee; paardenraces columnist, The Star, 1927-1932, Daily Mail, 1930-1932; toneelcriticus, Morning Post, 1928; oprichter, The Bucks Mail, 1930; redacteur, Sunday News, 1931; voorzitter van de raad van directeuren en filmschrijver/regisseur, British Lion Film Corporation. Militaire dienst: Royal West Regiment, Engeland, 1893-1896; Medical Staff Corps, Zuid Afrika, 1896-1899; kocht zijn ontslag af in 1899; diende bij de Lincoln's Inn afdeling van de Special Constabulary en als speciaal ondervrager voor het War Office, gedurende de Eerste Wereldoorlog. Lid van: Press Club, Londen (voorzitter, 1923-1924). Familie: getrouwd met 1. -

Shroud of the Squeaker

Shroud of the squeaker Ratkin (Evil) Tunnel Slaves* Infantry Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts Regiment(20) 6 5+ - 2+ 12 12/14 60 Yellow-Bellied Regiment(20) 6 5+ - 2+ 12 12/14 60 Yellow-Bellied Shock Troops Infantry Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts Horde(40) 6 4+ - 4+ 25 20/22 230 Crushing Strength (1), Elite, Rallying! (1), Vicious - Brew of Sharpness 45 Blight Infantry Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts Horde(40) 6 4+ - 3+ 30 -/21 205 Ensnare, Rallying! (1), Stealthy - Hammer of Measured Force 20 Brutes Large Infantry Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts Horde(6) 6 4+ - 4+ 18 13/16 185 Brutal, Crushing Strength (2), Fury, Rallying! (1), Regeneration (5+) - Brew of Courage 15 Weapon Team War Engine Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts (1) 6 - - 4+ 10 8/10 60 Breath Attack (10), Nimble, Piercing (1) - Storm of lead: Add Piercing (1) 20 (1) 6 - - 4+ 10 8/10 60 Breath Attack (10), Nimble, Piercing (1) - Storm of lead: Add Piercing (1) 20 Warlock Hero (Inf) Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts (1) 6 5+ - 4+ 1 9/11 90 Hero (Inf), Bane-chant (3), Blood Boil, Individual, Lightning Bolt (5) - Bane-chant (3) 20 - Blood Boil (L) 30 - Inspiring Talisman 20 Night Terror Hero (LrgInf) Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts (1) 9 3+ - 5+ 5 12/14 115 Hero (LrgInf), Crushing Strength (2), Height (2), Nimble - Orcish Skullpole 5 Demonspawn [1] Hero (Mon) Unit Size Sp Me Ra De At Ne Pts (1) 10 3+ - 5+ 13 16/18 290 Hero (Mon), Crushing Strength (3), Fly, Inspiring, Lightning Bolt (5), Rallying! (2) - Fly and Speed 10 50 1600 Bane-chant Spell. -

Tax Vote March 13 After Several Delays, the Equalized Valuation of Cass PUBLIC HEARINGS Kenneth Schott, 27, a Bay Cass City Village Council City of $15 Million

,. ,I .‘> CASS CITY CHR4, ONICLE CASS CITY, MICHIGAN-THURSDAY,FEBRUARY 1,1979 ’J,./. Twenty Cents EIGHTEEN PAGES J”(. 15, %. ’/A Council sets Village se. 9-e plant tax vote March 13 After several delays, the equalized valuation of Cass PUBLIC HEARINGS Kenneth Schott, 27, a Bay Cass City Village Council City of $15 million. county sheriff’s deputy, whs Tuesday evening finally set But as the SEV increases The updated village recre- hired as the new village the date for village residents in future years, the levy will ation facilities plan, pre- police officer, replacing Wil- to vote on a millage to pay drop each year and toward pared by Toshach and liam Moore, who resigned. , the local share for expansion the end of the 40 years, the Sobczak Associates, Inc., of He was one of 10 certified and improvement of the attorney predicted, resi- Saginaw, was reviewed. policemen who applied and wastewater treatment plant. dents might only be paying a one of two interviewed. Mar- The election will be Tues- half-mill a year. The plan is necessary in ried, his parents, the Frank day, March 13. order to apply for federal Schotts and in-laws, the Rdll Electors won’t be voting The village is under orders funds for recreation proj- Geigers, livein Cass City. fronl the state Water Re- ects. Village President Lam- on a set millage, but rather sources commission to im- to authorize levying of the The ,top priority in the bert Althaver discussed the millage necessary for Cass prove the sewage treatment possibility of the council plant and because of that, plan, for which the village establishing an economic City to pay offthe estimated will apply for federal funds $1.2 million local share for council members feel it development corporation. -

Inner Ball 12 Squeaker

US006935274B1 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent N0.: US 6,935,274 B1 Rothschild (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 30, 2005 (54) PET TOY 1,668,143 A * 5/1928 Daasch ..................... .. 473/571 2,687,302 A * 8/1954 Stiegler 473/571 Inventor: SuiteSteven 1100 MI Rothschild,Worcester MA Jackson(Us) 5,769,682 A * 6/1998 SChllliZDiResta . et. .a1. .. 446/184 01608_221b ’ 6,112,703 A * 9/2000 Handelsman 119/707 6,186,095 B1* 2/2001 Simon 119/707 . _ . 6,609,944 B1 * 8/2003 Viola .......... .. 446/409 (ak) Nome‘ sublectto any ‘3531mm? the grmé’f ?g; 2002/0134318 A1* 9/2002 Mann et a1. 119/709 gltsenct 1:523“; 02; a 111ste 11“ er 2004/0092198 A1* 5/2004 Ritchey ..................... .. 446/71 . y ays. FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS (21) Appl' NO‘ 10/ 609156 W0 WO 90/07961 * 7/1980 ........... .. A63F 9/00 (22) Filed: Jun. 25, 2003 * cited by examiner Related US. Application Data grim/1W Egan/WEE? M15931 _ _ _ _ ssistant xaminer— rea . a enti (60) 52031335211 apphcanon NO‘ 60/391328’ ?led on Jun‘ (74) Attorney, Agent, or Firm—Blodgett & Blodgett, PC. 57 ABSTRACT (51) Int. Cl.7 ..................... .. A01K 15/02; A01K 29/00; ( ) A63B 39/00; A63B 41/00; A63H 5/00 (52) us. Cl. ..................... .. 119/702;119/707; 119/709; The Pet 10y Consists of an inner 6195mm?“ ball having an 473/594; 473/595; 473/571; 446/397; 446/404; mner ball Wall, a squeaker mounted in the mner ball Wall, an 446/180; 446/188; 446/197; 446/168 outer elastomer ball having an outer ball Wall, an ‘air’ hole (58) Field of Search ~~~~~~~~~~~~~~ " 119/702 707 709_711_ mounted in the outer ball Wall, the mner ball being Within the D30/160; D21/713; 473/594, 595, 571, 397, outer ball. -

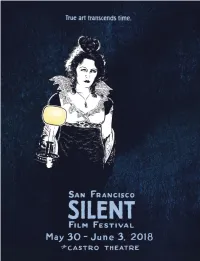

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

July to September 1917

Life at home: July to September 1917 Food shortages had led the Government The latest military activity also brought to try to ensure that as much land as more grim news to the parish: William and possible was ploughed up to grow crops. Harriet Silver in the High Street learnt that Captain Percy Seward of Weston Farm sat their son, George, had been killed. A few on the County Councils ‘War Agricultural weeks later, over the course of two days Committee’, trying to decide which at the beginning of the Passchendaele land should be ploughed, and also co- offensive, Rowland Marriner and Godfrey ordinating the co-operative use of horses Harfield were also killed. And after a wait and ploughs. of a year, the Chittys learnt that their son, Among many other imported goods, Caleb, had been declared dead, despite there was a shortage of wool, and his sister’s best efforts to find him alive. local children began to collect it from Some happier news included the hedgerows – perhaps giving some respite arrival of Kitty, a little daughter for Henry to local sparrows! Stevens (in the Somerset Light Infantry) Stormy weather in August caused and his wife Alice. And, although she some damage to hop blossoms, but when now lived down in Dorset, there was picking began at the start of September, also joy at the engagement of Mary the weather was glorious. There was, Ann, the daughter of Frederick Tussler, however, a big difference from previous a blacksmith and engineer at the lime years: with less acreage now given to works, to Quartermaster-Sergeant Charles hops, few outside hop-pickers were Downton, holder of a Meritorious Service required and there was not the normal Medal for conspicuous bravery. -

The Squeaker

The Squeaker December 2018 The village magazine of the parish of Langrish in Hampshire The Squeaker Page 1 The Squeaker IN MEMORIAM - BURITON Page 2 The Squeaker Office at Old Vicarage, Langrish, GU32 1QY Telephone: 01730 261354 Email: [email protected] [email protected] Website: www.squeaker.org.uk Issues on first day of September, December, March and June. Deadline for major copy, one month before issue! Information for the Websites: Squeaker website: - Please contact: [email protected] Parish Council news: Please contact: [email protected] Church news: Please contact [email protected] Information concerning advertisements/distribution: Please contact Doris Rattray on: [email protected] Editor Rosemary Hopewell Assistant Editor Ian Wesley Distributors Sylvia Deadman, Jan Mallett, Jenny Morris, Doris Rattray, Joy Sang, Bryony Southwell Printed at East Meon Vicarage - Our thanks to the Vicar Page 3 The Squeaker EDITORIAL ................................................................................................................................................ 5 PARISH AND COMMUNITY NEWS ............................................................................................................. 6 MANOR FARM DOVECOTE ....................................................................................................................... 7 LANGRISH AND RAMSDEAN FRIENDS FACEBOOK GROUP ........................................................................ 8 BOOK REVIEW - LANGRISH BOOK CLUB ................................................................................................... -

The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction Limits Spontaneous Exploration and Discovery

The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction Limits Spontaneous Exploration and Discovery The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Bonawitz, Elizabeth, Patrick Shafto, Hyowon Gweon, Noah D. Goodman, Elizabeth Spelke, and Laura Schulz. 2011. The double-edged sword of pedagogy: Instruction limits spontaneous exploration and discovery. Cognition 120(3): 322-330. Published Version doi:10.1016/j.cognition.2010.10.001 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:10265480 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Open Access Policy Articles, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#OAP The Double-edged Sword of Pedagogy: Instruction limits spontaneous exploration and discovery 1* 2 3 4 5 Elizabeth Bonawitz , Patrick Shafto !, Hyowon Gweon , Noah D. Goodman , Elizabeth Spelke , & Laura Schulz3 In press, Cognition 1 Department of Psychology, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA 94720 USA 2 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292 USA 3 Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge MA 02139 USA 4 Department of Psychology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA 94305 USA 5 Department of Psychology, Harvard University, Cambridge MA 02138 USA ! The first two authors contributed equally to this work. Abstract Motivated by computational analyses, we look at how teaching affects exploration and discovery. In Experiment 1, we investigated children’s exploratory play after an adult pedagogically demonstrated a function of a toy, after an interrupted pedagogical demonstration, after a naïve adult demonstrated the function, and at baseline. -

The Double-Edged Sword of Pedagogy: Modeling the Effect of Pedagogical Contexts on Preschoolers’ Exploratory Play

The Double-edged Sword of Pedagogy: Modeling the Effect of Pedagogical Contexts on Preschoolers’ Exploratory Play Elizabeth Bonawitz 1∗, Patrick Shafto 2*, Hyowon Gweon 1, Isabel Chang 1, Sydney Katz 1, & Laura Schulz 1 1 ([email protected]) Department of Brain and Cognitive Sciences, MIT, Cambridge, MA 02139 USA 2 Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY 40292 USA Abstract not looked at how children’s inferences affect their exploratory behavior. How does explicit instruction affect exploratory play and learning? We present a model that captures pedagogical assumptions Given that children learn both from spontaneous (adapted from Shafto and Goodman, 2008) and test the model with exploration and explicit instruction, how does explicit a novel experiment looking at 4-year-olds’ exploratory play in instruction affect exploratory play and learning? In pedagogical and non-pedagogical contexts. Our findings are pedagogical situations, it is reasonable for learners to expect consistent with the model predictions: preschool children limit that the teacher is helping them learn; this expectation may their exploration in pedagogical contexts, spending most of their facilitate learning in novel situations (Klahr & Nigam, 2004; free play performing only the demonstrated action. By contrast, Csbra & Gergely, in press). Learning the affordances of a children explore broadly both at baseline and after an accidental novel artifact is challenging because for any object, there demonstration. Thus pedagogy constrains children’s exploration are an unknown, and potentially large, number of causal for better and for worse; children learn the demonstrated causal relationship but are less likely than children in non-pedagogical properties. -

Wędrówki Po Bibliografii: Edgar Wallace

Jerzy Gronau WĘDRÓWKI PO BIBLIOGRAFII ANGIELSKIEGO AUTORA POWIEŚCI SENSACYJNO-KRYMINALNYCH EDGARA WALLACE (Richard Horatio) Edgar Wallace (1875-1932) Kraków 2004 1 Jerzy GRONAU – Wędrówki po BIBLIOGRAFII Edgara WALLACE `a 2 Wstęp: Genezą tego opracowania były: - moja emerytura, - chęć powtórzenia swego rodzaju „zabawy umysłowej” którą przeżyłem przy innej pracy podobnego charakteru, - konstatacja o braku w polskim piśmiennictwie bibliografii tegoż autora. Już w dobrze zaawansowanej pracy, zdobyłem niedostępną w Polsce bibliografię „The British Bibliography of Edgar Wallace” z roku 1969, która stała się podstawą zreorganizowania moich dotychczasowych zapisów, dotyczących angielskich wydań tego autora. By rozszerzyć zakres informacji, dodałem również informacje o wydaniach w polskim języku, jak i w niemieckim oraz francuskim, które jednak z braku dostępnych źródeł są niepełne. Polskie przekłady różnych tłumaczy względnie opracowywujących nowe wydania, ukazywały się tak przed drugą wojną, jak i po niej. Wydało je kilkanaście wydawnictw, pod różnymi tytułami – bez odniesienia się do tytułu oryginału. Niestety informacje o przedwojennych przekładach pochodzą ze źródeł wtórnych, bowiem nie możliwym stało się obecnie zdobycie nie „zaczytanych” egzemplarzy, które w niektórych bibliotekach figurują raczej jako zniszczone lub zagubione egzemplarze. Muszę tutaj nadmienić, że nie znalazłem w swoich poszukiwaniach dotąd polskiej biblioteki tak naukowej jak i publicznej z pełnym kompletem powojennych wydań tego autora. Zresztą podobnie jest z wydawnictwami zgranicznymi- tam też trudno trafić na większy zbiór wydanych książek tego autora. Moje niniejsze opracowanie składa się z szeregu tabel, częściowo uporządkowanych wg bibliografii jak wyżej ze znakiem numeru kodu, jak również alfabetycznie i rokiem wydania książki. Myślę, że opracowania te przydadzą się dla poszukujących informacji bibliograficznych, choć zdaję sobie sprawę, że nie wyczerpują w pełni tego tematu. -

Award Winning Educational Toys Learning Through Play

2015/16 Award winning educational toys Learning through Play Welcome to TOLO Toys and our award winning See our range of high quality pre-school toys. website TOLO are committed to the development of an exciting range of products that stimulate and encourage young developing minds whilst offering excellent play value along with fun and excitement during a child’s formative years. The TOLO range of products is designed with safety and durability at the forefront of our minds. We only use the highest grade materials whilst manufacturing, and rigorous testing procedures ensure that our quality standards remain consistently high. Contents Activity Centres 03 Rattles and Teethers 04 Stacking Toys and Roly Polys 05 Shape Sorters 06 Pop Ups and Carousels 07 Bath Toys 08 Musicial Instruments 09 Plush Toys 09 First Friends at Home 10 First Friends Road and Rail Sets 11 First Friends on the Farm 12/13 First Friends Animals of the World 14/15 First Friends Dinosaur World 16 Key: Boxed 3 inner pack quantity Tagged 6 inner pack quantity 02 A new born baby is a bundle of joy eager to begin experiencing the world they have just entered. TOLO’s high quality rattles and teethers, stimulating activity centres, stacking toys, shape sorter and bath toys encourage early development for babies and young children through sound, shape and colour recognition. Activity Centres 87130 carry handle Musical Activity T.V. 0m+ • Musical, with an easy wind movement. • Plays a delightful melody. • Moving screen entertains baby. • Squeaking, rattling, spinning fun! • Strong handle for carrying. • Attaches to crib or playpen. -

Lar Press and Film, 1919-1939

ORBIT - Online Repository of Birkbeck Institutional Theses Enabling Open Access to Birkbeck’s Research Degree output The representation of London nights in British popu- lar press and film, 1919-1939 https://eprints.bbk.ac.uk/id/eprint/40490/ Version: Public Version Citation: Arts, Mara (2020) The representation of London nights in British popular press and film, 1919-1939. [Thesis] (Unpublished) c 2020 The Author(s) All material available through ORBIT is protected by intellectual property law, including copy- right law. Any use made of the contents should comply with the relevant law. Deposit Guide Contact: email The Representation of London Nights in British Popular Press and Film, 1919-1939 Candidate name: Mara Arts Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Birkbeck, University of London 1 Declaration of original work I hereby confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. 2 Abstract This thesis explores the representation of night-time activities in the capital in popular British newspapers and films of the period. It argues that, whilst an increasingly democratised night allowed for more opportunities for previously marginalised groups, popular media of the period largely promoted adherence to the status quo. The thesis draws on extensive primary source material, including eighty British feature films and newspaper samples of the Daily Mail, Daily Express and Daily Mirror to systematically analyse the representation of London’s nightlife in the British interwar period. This period saw the consolidation of the popular daily newspaper industry and, after government intervention, an expansion of the domestic film industry. The interwar period also saw great social change with universal suffrage, technological developments and an economic crisis.