The Case of Myanmar's Mega-Dams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Damming the Irrawaddy Contact [email protected]

Damming the Irrawaddy Contact [email protected] Acknowledgements We would like to thank the donors that supported this report project. We thank DCMF and GGF for support to begin the initial research and writing. We thank BRC for their ongoing support, and E-desk and ERI for their technical assistance. Most importantly we would like to say thanks to our staff and field researchers from the KDNG network, including from the Kachin Environmental Organization and All Kachin Students and Youth Union, and other environmental organizations from Burma that gave us suggestions and advice. Kachin Development Networking Group (KDNG) KDNG is a network of Kachin civil society groups and development organizations inside Kachin State and overseas that was set up in 2004. KDNGs purpose is to effectively work for sustainable development together with locally-based organizations in Kachin State. Its aim is to promote a civil society based on equality and justice for the local people in the struggle for social and political change in Burma.KDNG is a network of Kachin civil society groups and development organizations inside Kachin State and overseas that was set up in 2004. KDNGs purpose is to effectively work for sustainable development together with locally-based organizations in Kachin State. Its aim is to promote a civil society based on equality and justice for the local people in the struggle for social and political change in Burma. Kachin Environmental Organization (KEO) is a member of the KDNG and is the main author of this report. Kachin Environmental Organization The Kachin Environmental Organization (KEO) was formed in April 2004 by Kachin people concerned about environment issues inside Kachin State, especially the rapid loss of natural resources. -

(Mong Ton) Dam March 10, 2015: Shan

Detailed timeline of community opposition to SMEC’s EIA/SIA process for the Upper Salween (Mong Ton) dam March 10, 2015: Shan and Karen representatives protest at SMEC public meeting in Taunggyi SMEC held a public meeting in Taunggyi, Shan State. At the meeting, about 30 Karen and Shan people protested by wearing “No Dam” headbands, holding up posters against the Salween dams, and publicly raising many questions about the planned EIA/SIA process. However, the description of this “first public EIA/SIA scoping meeting” on the official Mong Ton Hydropower Project website makes no mention of the protest. (http://www.mongtonhydro.com/eportal/ui?pageId=132488&articleKey=134488&columnId=132537) April 6, 2015: About 150 villagers protest at SMEC public meeting in Mong Ton About 150 local villagers protested against the Mong Ton dam during a meeting organized by SMEC in Mong Ton, southern Shan State, Burma on April 6, 2015. The villagers, from different areas of Mong Ton, raised placards against the dam, and handed a statement to SMEC staff, raising concerns about the lack of lasting peace, and the potential flooding of many towns, villages and temples, particularly in Kunhing Township. The consultation was mainly attended by government officials and other pro-government groups, including local militia, and villagers said that they had little opportunity to ask questions. After the consultation, the villagers went to Pittakat Hong Dhamma temple, and held a ceremony to pray for the protection of the Salween River. The local branches of the two main Shan parties, Shan Nationalities Democratic Party (SNDP) and Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD), issued statements against the Mong Ton dam on the day of the meeting. -

The Union Report the Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Census Report Volume 2

THE REPUBLIC OF THE UNION OF MYANMAR The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report The Union Report : Census Report Volume 2 Volume Report : Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population May 2015 The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census The Union Report Census Report Volume 2 For more information contact: Department of Population Ministry of Immigration and Population Office No. 48 Nay Pyi Taw Tel: +95 67 431 062 www.dop.gov.mm May, 2015 Figure 1: Map of Myanmar by State, Region and District Census Report Volume 2 (Union) i Foreword The 2014 Myanmar Population and Housing Census (2014 MPHC) was conducted from 29th March to 10th April 2014 on a de facto basis. The successful planning and implementation of the census activities, followed by the timely release of the provisional results in August 2014 and now the main results in May 2015, is a clear testimony of the Government’s resolve to publish all information collected from respondents in accordance with the Population and Housing Census Law No. 19 of 2013. It is my hope that the main census results will be interpreted correctly and will effectively inform the planning and decision-making processes in our quest for national development. The census structures put in place, including the Central Census Commission, Census Committees and Offices at all administrative levels and the International Technical Advisory Board (ITAB), a group of 15 experts from different countries and institutions involved in censuses and statistics internationally, provided the requisite administrative and technical inputs for the implementation of the census. -

STATUS and CONSERVATION of FRESHWATER POPULATIONS of IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D

WORKING PAPER NO. 31 MAY 2007 STATUS AND CONSERVATION OF FRESHWATER POPULATIONS OF IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D. Smith, Robert G. Shore and Alvin Lopez WORKING PAPER NO. 31 MAY 2007 sTATUS AND CONSERVATION OF FRESHWATER POPULATIONS OF IRRAWADDY DOLPHINS Edited by Brian D. Smith, Robert G. Shore and Alvin Lopez WCS Working Papers: ISSN 1530-4426 Copies of the WCS Working Papers are available at http://www.wcs.org/science Cover photographs by: Isabel Beasley (top, Mekong), Danielle Kreb (middle, Mahakam), Brian D. Smith (bottom, Ayeyarwady) Copyright: The contents of this paper are the sole property of the authors and cannot be reproduced without permission of the authors. The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) saves wildlife and wild lands around the world. We do this through science, conservation, education, and the man- agement of the world's largest system of urban wildlife parks, led by the flag- ship Bronx Zoo. Together, these activities inspire people to imagine wildlife and humans living together sustainably. WCS believes that this work is essential to the integrity of life on earth. Over the past century, WCS has grown and diversified to include four zoos, an aquarium, over 100 field conservation projects, local and international educa- tion programs, and a wildlife health program. To amplify this dispersed con- servation knowledge, the WCS Institute was established as an internal “think tank” to coordinate WCS expertise for specific conservation opportunities and to analyze conservation and academic trends that provide opportunities to fur- ther conservation effectiveness. The Institute disseminates WCS' conservation work via papers and workshops, adding value to WCS' discoveries and experi- ence by sharing them with partner organizations, policy-makers, and the pub- lic. -

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020

USAID/BURMA MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT January 2020 Contract Number: 72048218C00004 Myanmar Analytical Activity Acknowledgement This report has been written by Kimetrica LLC (www.kimetrica.com) and Mekong Economics (www.mekongeconomics.com) as part of the Myanmar Analytical Activity, and is therefore the exclusive property of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). Melissa Earl (Kimetrica) is the author of this report and reachable at [email protected] or at Kimetrica LLC, 80 Garden Center, Suite A-368, Broomfield, CO 80020. The author’s views in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. USAID.GOV DECEMBER 2019 MONTHLY ATMOSPHERIC REPORT | 1 JANUARY 2020 AT A GLANCE Myanmar’s ICOE Finds Insufficient Evidence of Genocide. The ICOE admits there is evidence that Tatmadaw soldiers committed individual war crimes, but rules there is no evidence of a systematic effort to destroy the Rohingya people. (Page 1) The ICJ Rules Myanmar Must Take Measures to Protect the Rohingya From Acts of Genocide. International observers laud the ruling as a major step toward fighting genocide globally, but reactions to the ruling in Myanmar are mixed. (Page 2) Fortify Rights Documents Five Cases of Rohingya IDPs Forced to Accept NVCs. The international community and the Rohingya condemned the cards, saying they are a means to keep the Rohingya from obtaining full citizenship rights by identifying them as “Bengali,” not Rohingya. (Page 3) During the Chinese President’s State Visit to Myanmar, the Two Countries Signed Multiple MoUs. The 33 MoUs that President Xi Jinping cosigned are related to infrastructure, trade, media, and urban development. -

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar

Ethnic Armed Actors and Justice Provision in Myanmar Brian McCartan and Kim Jolliffe October 2016 Preface As a result of decades of ongoing civil war, large areas of Myanmar remain outside government rule, or are subject to mixed control and governance by the government and an array of ethnic armed actors (EAAs). These included ethnic armed organizations, with ceasefires or in conflict with the state, as well as state-backed ethnic paramilitary organizations, such as the Border Guard Forces and People’s Militia Forces. Despite this complexity, order has been created in these areas, in large part through customary justice mechanisms at the community level, and as a result of justice systems administered by EAAs. Though the rule of law and the workings of Myanmar’s justice system are receiving increasing attention, the role and structure of EAA justice systems and village justice remain little known and therefore, poorly understood. As such, The Asia Foundation is pleased to present this research on justice provision and ethnic armed actors in Myanmar, as part of the Foundation’s Social Services in Contested Areas in Myanmar series. The study details how the village, and village-based mechanisms, are the foundation of stability and order for civilians in most of these areas. These systems have then been built through EAA justice systems, which maintain a hierarchy of courts above the village level. Understanding the continuity and stability of these village systems, and the heterogeneity of the EAA justice systems which work alongside them, is essential for understanding civilians’ experiences of justice and security across Myanmar, as well as the opportunities for positive change that exist in Myanmar’s ongoing peace process and governance reforms. -

THE STATE of LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS in KACHIN Photo Credits

Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN KACHIN Photo credits Mike Adair Emilie Röell Myanmar Survey Research A photo record of the UNDP Governance Mapping Trip for Kachin State. Travel to Tanai, Putao, Momauk and Myitkyina townships from Jan 6 to Jan 23, 2015 is available here: http://tinyurl.com/Kachin-Trip-2015 The views expressed in this publication are those of the author, and do not necessarily represent the views of UNDP. Local Governance Mapping THE STATE OF LOCAL GOVERNANCE: TRENDS IN KACHIN UNDP MYANMAR Table of Contents Acknowledgements II Acronyms III Executive Summary 1 1. Introduction 5 2. Kachin State 7 2.1 Kachin geography 9 2.2 Population distribution 10 2.3 Socio-economic dimensions 11 2.4 Some historical perspectives 13 2.5 Current security situation 18 2.6 State institutions 18 3. Methodology 24 3.1 Objectives of mapping 25 3.2 Mapping tools 25 3.3 Selected townships in Kachin 26 4. Governance at the front line – Findings on participation, responsiveness and accountability for service provision 27 4.1 Introduction to the townships 28 4.1.1 Overarching development priorities 33 4.1.2 Safety and security perceptions 34 4.1.3 Citizens’ views on overall improvements 36 4.1.4 Service Provider’s and people’s views on improvements and challenges in selected basic services 37 4.1.5 Issues pertaining to access services 54 4.2 Development planning and participation 57 4.2.1 Development committees 58 4.2.2 Planning and use of development funds 61 4.2.3 Challenges to township planning and participatory development 65 4.3 Information, transparency and accountability 67 4.3.1 Information at township level 67 4.3.2 TDSCs and TMACs as accountability mechanisms 69 4.3.3 WA/VTAs and W/VTSDCs 70 4.3.4 Grievances and disputes 75 4.3.5 Citizens’ awareness and freedom to express 78 4.3.6 Role of civil society organisations 81 5. -

Myitsone Hydroelectric Dam Myanmar

Myitsone hydroelectric dam Myanmar Sectors: Hydroelectric Power Generation On record This profile is no longer actively maintained, with the information now possibly out of date Send feedback on this profile By: BankTrack Created before Nov 2016 Last update: Oct 12 2016 Contact: Project website Sectors Hydroelectric Power Generation Location About Myitsone hydroelectric dam The Myitsone Hydroelectric Project is the largest of seven dams (total capacity 13,360MW) planned on the headwaters of the Irrawaddy (confluence of Mali Hka, and N’Mai Hka rivers) in Burma. The USD$3.6 billion project is located in an area recognized as one of the world’s eight hotspots of biodiversity, and will submerge “the birthplace of Burma” in local myths, including a number of historical churches and temples, and the sacred banyan tree. There are serious doubts about the quality and independence of the Environmental Impact Assessment for this mega-dam project, as well as concerns regarding the resettlement process and the role of the project in exacerbating the long-standing conflict between the ethnic Kachin people and the military government. Latest developments Project Status Apr 19 2012 What must happen The project must be cancelled because of the local opposition and continued fighting caused by the project in Kachin State. There must be an independent and comprehensive investigation of the environmental and social impacts including downstream impacts, of the remaining 6 dams planned on the headwaters of the Irrawaddy River. Impacts Social and human rights impacts Thousands of people’s livelihoods are directly impacted by the Myitsone project. The government has underreported the number of people directly affected by the dam as few as 2146 people from five villages will be relocated to new homes. -

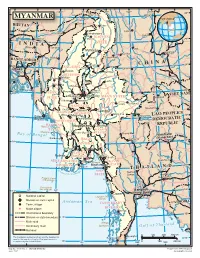

Map of Myanmar

94 96 98 J 100 102 ° ° Indian ° i ° ° 28 n ° Line s Xichang Chinese h a MYANMAR Line J MYANMAR i a n Tinsukia g BHUTAN Putao Lijiang aputra Jorhat Shingbwiyang M hm e ra k Dukou B KACHIN o Guwahati Makaw n 26 26 g ° ° INDIA STATE n Shillong Lumding i w d Dali in Myitkyina h Kunming C Baoshan BANGLADE Imphal Hopin Tengchong SH INA Bhamo C H 24° 24° SAGAING Dhaka Katha Lincang Mawlaik L Namhkam a n DIVISION c Y a uan Gejiu Kalemya n (R Falam g ed I ) Barisal r ( r Lashio M a S e w k a o a Hakha l n Shwebo w d g d e ) Chittagong y e n 22° 22° CHIN Monywa Maymyo Jinghong Sagaing Mandalay VIET NAM STATE SHAN STATE Pongsali Pakokku Myingyan Ta-kaw- Kengtung MANDALAY Muang Xai Chauk Meiktila MAGWAY Taunggyi DIVISION Möng-Pan PEOPLE'S Minbu Magway Houayxay LAO 20° 20° Sittwe (Akyab) Taungdwingyi DEMOCRATIC DIVISION y d EPUBLIC RAKHINE d R Ramree I. a Naypyitaw Loikaw w a KAYAH STATE r r Cheduba I. I Prome (Pye) STATE e Bay Chiang Mai M kong of Bengal Vientiane Sandoway (Viangchan) BAGO Lampang 18 18° ° DIVISION M a e Henzada N Bago a m YANGON P i f n n o aThaton Pathein g DIVISION f b l a u t Pa-an r G a A M Khon Kaen YEYARWARDY YangonBilugyin I. KAYIN ATE 16 16 DIVISION Mawlamyine ST ° ° Pyapon Amherst AND M THAIL o ut dy MON hs o wad Nakhon f the Irra STATE Sawan Nakhon Preparis Island Ratchasima (MYANMAR) Ye Coco Islands 92 (MYANMAR) 94 Bangkok 14° 14° ° ° Dawei (Krung Thep) National capital Launglon Bok Islands Division or state capital Andaman Sea CAMBODIA Town, village TANINTHARYI Major airport DIVISION Mergui International boundary 12° Division or state boundary 12° Main road Mergui n d Secondary road Archipelago G u l f o f T h a i l a Railroad 0 100 200 300 km Chumphon The boundaries and names shown and the designations Kawthuang 10 used on this map do not imply official endorsement or ° acceptance by the United Nations. -

Environmental Flows for the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River Basin, Myanmar

UNESCO-IHE Online Course on Environmental Flows Environmental Flows for the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River Basin, Myanmar Written by Alison Simmance MSc BSc April. 2013 E:[email protected] Environmental Flows for the Ayeyarwady River Basin, A.Simmance Environmental Flows for the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River Basin, Myanmar UNESCO-IHE Online Course on Environmental Flows Citation: Simmance, A. 2013. Environmental Flows for the Ayeyarwady (Irrawaddy) River Basin, Myanmar. Unpublished. UNESCO-IHE Online Course on Environmental Flows. Environmental Flows for the Ayeyarwady River Basin, A.Simmance Table of Contents 1. Chapter 1: Introduction to the Ayeyarwady River Basin 2 1.1. Overview- Country Context 2 1.2. Introduction to the Ayeyarwady River Basin 4 1.2.1. Hydrological Characteristics of the Ayeyarwady River Basin 4 1.2.2. Climate 5 1.3. The Ayeyarwady River Basin’s Natural Resources 6 1.3.1. Biodiversity and Conservation 6 1.3.2. Habitats 9 1.3.3. Watersheds and Freshwater Resources 10 1.3.4. Oil and Gas 11 1.3.5. Minerals 11 1.4. Socio-economic Conditions of the Ayeyarwady River Basin 11 1.5. Problems and Issues in the Ayeyarwady River Basin 12 1.5.1. Irrigation and drainage development 13 1.5.2. Hydropower Developments 13 1.5.3. Land-use change and Deforestation 15 1.5.4. Oil and Gas Extraction 16 1.5.5. Mining 16 1.5.6. Climate Change 17 1.5.7. Unsustainable Fishing Practices 18 1.5.8. Biodiversity Loss 18 1.5.9. Conclusions 18 2. Chapter 2: Governance of Natural Resource Management in the Ayeyarwady River Basin 19 2.1. -

1 Testimony Before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review

Date of the hearing: January 26, 2012. Title of the hearing: China’s Global Quest for Resources and Implications for the United States Name of panelist: Brahma Chellaney Panelist’s title and organization: Professor of Strategic Studies, Center for Policy Research, New Delhi. Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission China has pursued an aggressive strategy to secure (and even lock up) supplies of strategic resources like water, energy and mineral ores. Gaining access to or control of resources has been a key driver of its foreign and domestic policies. China, with the world’s most resource-hungry economy, is pursuing the world’s most-assertive policies to gain control of important resources. Much of the international attention on China’s resource strategy has focused on its scramble to secure supplies of hydrocarbons and mineral ores. Such attention is justified by the fact that China is seeking to conserve its own mineral resources and rely on imports. For example, China, a major steel consumer, has substantial reserves of iron ore, yet it has banned exports of this commodity. It actually encourages its own steel producers to import iron ore. China, in fact, has emerged as the largest importer of iron ore, accounting for a third of all global imports. India, in contrast, remains a major exporter of iron ore to China, although the latter has iron-ore deposits more than two-and-half times that of India. But while buying up mineral resources in foreign lands, China now supplies, according to one estimate, about 95 per cent of the world’s consumption of rare earths — a precious group of minerals vital to high- technology industry, such as miniaturized electronics, computer disk drives, display screens, missile guidance, pollution-control catalysts, and advanced materials. -

Kahrl Navigating the Border Final

CHINA AND FOREST TRADE IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC REGION: IMPLICATIONS FOR FORESTS AND LIVELIHOODS NAVIGATING THE BORDER: AN ANALYSIS OF THE CHINA- MYANMAR TIMBER TRADE Fredrich Kahrl Horst Weyerhaeuser Su Yufang FO RE ST FO RE ST TR E ND S TR E ND S COLLABORATING INSTITUTIONS Forest Trends (http://www.forest-trends.org): Forest Trends is a non-profit organization that advances sustainable forestry and forestry’s contribution to community livelihoods worldwide. It aims to expand the focus of forestry beyond timber and promotes markets for ecosystem services provided by forests such as watershed protection, biodiversity and carbon storage. Forest Trends analyzes strategic market and policy issues, catalyzes connections between forward-looking producers, communities, and investors and develops new financial tools to help markets work for conservation and people. It was created in 1999 by an international group of leaders from forest industry, environmental NGOs and investment institutions. Center for International Forestry Research (http://www.cifor.cgiar.org): The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), based in Bogor, Indonesia, was established in 1993 as a part of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) in response to global concerns about the social, environmental, and economic consequences of forest loss and degradation. CIFOR research produces knowledge and methods needed to improve the wellbeing of forest-dependent people and to help tropical countries manage their forests wisely for sustained benefits. This research is conducted in more than two dozen countries, in partnership with numerous partners. Since it was founded, CIFOR has also played a central role in influencing global and national forestry policies.