Exposing Narrative Ideologies of Victimhood in Emma Donaghue's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gone Girl : a Novel / Gillian Flynn

ALSO BY GILLIAN FLYNN Dark Places Sharp Objects This author is available for select readings and lectures. To inquire about a possible appearance, please contact the Random House Speakers Bureau at [email protected] or (212) 572-2013. http://www.rhspeakers.com/ This book is a work of ction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used ctitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. Copyright © 2012 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Dark Places” copyright © 2009 by Gillian Flynn Excerpt from “Sharp Objects” copyright © 2006 by Gillian Flynn All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Crown Publishers, an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. www.crownpublishing.com CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Flynn, Gillian, 1971– Gone girl : a novel / Gillian Flynn. p. cm. 1. Husbands—Fiction. 2. Married people—Fiction. 3. Wives—Crimes against—Fiction. I. Title. PS3606.L935G66 2012 813’.6—dc23 2011041525 eISBN: 978-0-307-58838-8 JACKET DESIGN BY DARREN HAGGAR JACKET PHOTOGRAPH BY BERND OTT v3.1_r5 To Brett: light of my life, senior and Flynn: light of my life, junior Love is the world’s innite mutability; lies, hatred, murder even, are all knit up in it; it is the inevitable blossoming of its opposites, a magnicent rose smelling faintly of blood. -

1 Unlikability and Female Villains in the Works of Gillian Flynn Cannon

1 Unlikability and Female Villains in the Works of Gillian Flynn Cannon Elder Lane High Point, North Carolina Bachelor of Arts, English, University of Virginia, 2017 Bachelor of Arts, Spanish, University of Virginia, 2017 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of English University of Virginia May 2018 2 Introduction: In recent years, television and popular fiction have begun to feature a new type of female character termed the “unlikable” woman. From popular novels such as Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl and Paula Hawkins’ The Girl on the Train to TV shows such as Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s Fleabag and Lena Dunham’s Girls, popular cultural products in recent years have begun to center on a depiction of women distinct from any before—at least in terminology.1 In each of these works, female writers depict troubled women, from murderers and alcoholics to narcissists, each unwilling to conform to the standards and expectations of representations of women. In each of these works, the authors of these characters refuse to position them as role models, instead focusing on their extreme negative capacity, presenting their story arcs not as ones of redemption or correction, but as ones of continuous development and iteration of personal defect. Against the trend of hailing positive representations of women in fiction, these flawed and profoundly human characters slide the scale in the opposite direction. Instead of proving the equal intelligence, strength, and positive capacity of women, these characters work to accentuate the negative. -

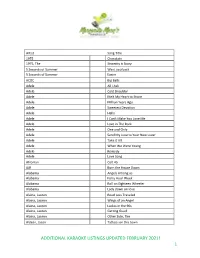

Additional Karaoke Listings Updated February 2021! 1

Artist Song Title 1975 Chocolate 1975, The Sincerity is Scary 5 Seconds of Summer Want you back 5 Seconds of Summer Easier ACDC Big Balls Adele All I Ask Adele Cold Shoulder Adele Melt My Heart to Stone Adele Million Years Ago Adele Sweetest Devotion Adele Hello Adele I Can't Make You Love Me Adele Love in The Dark Adele One and Only Adele Send My Love to Your New Lover Adele Take It All Adele When We Were Young Adele Remedy Adele Love Song Afroman Colt 45 AJR Burn the House Down Alabama Angels Among us Alabama Forty Hour Week Alabama Roll on Eighteen Wheeler Alabama Lady down on love Alaina, Lauren Road Less Traveled Alaina, Lauren Wings of an Angel Alaina, Lauren Ladies in the 90s Alaina, Lauren Getting Good Alaina, Lauren Other Side, The Aldean, Jason Tattoos on this town ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 1 Aldean, Jason Just Getting Started Aldean, Jason Lights Come On Aldean, Jason Little More Summertime, A Aldean, Jason This Plane Don't Go There Aldean, Jason Tonight Looks Good On You Aldean, Jason Gettin Warmed up Aldean, Jason Truth, The Aldean, Jason You make it easy Aldean, Jason Girl Like you Aldean, Jason Camouflage Hat Aldean, Jason We Back Aldean, Jason Rearview Town Aldean, Jason & Miranda Lambert Drowns The Whiskey Alice in Chains Man In The Box Alice in Chains No Excuses Alice in Chains Your Decision Alice in Chains Nutshell Alice in Chains Rooster Allan, Gary Every Storm (Runs Out of Rain) Allan, Gary Runaway Allen, Jimmie Best shot Anderson, John Swingin' Andress, Ingrid Lady Like Andress, Ingrid More Hearts Than Mine Angels and Airwaves Kiss & Tell Angston, Jon When it comes to loving you Animals, The Bring It On Home To Me Arctic Monkeys Do I Wanna Know Ariana Grande Breathin Arthur, James Say You Won't Let Go Arthur, James Naked Arthur, James Empty Space ADDITIONAL KARAOKE LISTINGS UPDATED FEBRUARY 2021! 2 Arthur, James Falling like the stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite the Stars Arthur, James & Anne Marie Rewrite The Stars Ashanti Happy Ashanti Helpless (ft. -

Female Anti-Heroes in Contemporary Literature, Film, and Television Sara A

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Female Anti-Heroes in Contemporary Literature, Film, and Television Sara A. Amato Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Amato, Sara A., "Female Anti-Heroes in Contemporary Literature, Film, and Television" (2016). Masters Theses. 2481. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2481 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� f.AsTE�ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, andDistribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Final Song Blonde Dangerous Woman 1 the Chainsmokers Feat

29 August 2016 CHART #2049 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Final Song Blonde Dangerous Woman 1 The Chainsmokers feat. Halsey 21 M0 1 Frank Ocean 21 Ariana Grande Last week 2 / 4 weeks Disruptor/SonyMusic Last week 24 / 6 weeks SonyMusic Last week - / 1 weeks BoysDon'tCry Last week 26 / 14 weeks Republic/Universal Cold Water Cheap Thrills Suicide Squad OST All Over The World: The Best Of 2 Major Lazer feat. Justin Bieber And... 22 Sia 2 Various 22 ELO Last week 1 / 5 weeks Gold / Because/Warner Last week 23 / 27 weeks Platinum x2 / Inertia/Rhythm Last week 1 / 3 weeks Atlantic/Warner Last week 24 / 19 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Let Me Love You This Girl 25 Lemonade 3 DJ Snake feat. Justin Bieber 23 Kungs And Cookin' On 3 Burners 3 Adele 23 Beyonce Last week 3 / 3 weeks Interscope/Universal Last week 22 / 8 weeks KungsMusic/Universal Last week 4 / 40 weeks Platinum x7 / XL/Rhythm Last week 34 / 18 weeks Gold / Columbia/SonyMusic Heathens Starving Views A Head Full Of Dreams 4 Twenty One Pilots 24 Hailee Steinfeld And Grey feat. Zedd 4 Drake 24 Coldplay Last week 4 / 10 weeks Gold / Atlantic/Warner Last week - / 1 weeks Republic/Universal Last week 3 / 17 weeks CashMoney/Universal Last week - / 33 weeks Gold / Parlophone/Warner Don't Worry Bout It Hurts So Good Blurryface Kaleidoscope World 5 Kings 25 Astrid S 5 Twenty One Pilots 25 The Chills Last week 7 / 7 weeks Gold / ArchAngel/Warner Last week 18 / 5 weeks Universal Last week 2 / 33 weeks Gold / FueledByRamen/Warner Last week - / 11 weeks FlyingNun/FlyingOut One Dance Never Be Like You Poi E: The Story Of Our Song Major Key 6 Drake feat. -

Download the Gone Girl Screenplay PDF for Personal, Private

SCRIPT TITLE Written by Name of First Writer Based on, If Any Address Phone Number BLACK SCREEN NICK (V.O.) When I think of my wife, I always think of her head. FADE IN: INT. BEDROOM-SOMETIME We see the back of AMY DUNNE’S HEAD, resting on a pillow. NICK (V.O.) I picture cracking her lovely skull, unspooling her brain, Nick runs his fingers into Amy’s hair. NICK (V.O.) Trying to get answers. He twirls and twirls a lock, a screw tightening. NICK (V.O.) The primal questions of a marriage: What are you thinking? How are you feeling? What have we done to each other? AMY wakes, turns, gives a look of anger...or alarm. NICK (V.O.) What will we do? BLACK SCREEN EXT. CARTHAGE - MORNING The sun rises on the small town of Carthage, Missouri. We see in flashes: A giant decrepit MEGAMALL, boarded up, a series of downtown buildings with CLOSED or FOR SALE signs. A carved marble entry—reading FOREST GLEN—ushers us into a ruined HOUSING DEVELOPMENT. The majority of McMansions are empty. FORECLOSED, FOR SALE signs everywhere. The place has an almost bucolic air: swaying grasses, stray wildlife. EXT.- NICK DUNNE’S BACKYARD - DAWN TITLE CARD: THE MORNING OF 2. Nick Dunne, 30s, handsome, is watching bits of trash float along the Mississippi River; a McMansion behind him. His yard is the only one mowed—all around him wilderness encroaches. The SUN rises over the treeline and blares its FIRST-DEGREE SPOTLIGHT in his face. He looks, fearful, ill. -

Dark Places” (2009): a Marxist Feminist Theory

WOMAN STRUGGLE EXPERIENCED BY PATTY DAY IN GILLIAN FLYNN’S “DARK PLACES” (2009): A MARXIST FEMINIST THEORY Submitted as a Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for getting Bachelor Degree of Education in English Department by: ANDHIKA WAHYU RUSTAMAJI A320150008 DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH EDUCATION SCHOOL OF TEACHER TRAINING AND EDUCATION UNIVERSITAS MUHAMMADIYAH SURAKARTA 2020 i ii iii WOMAN STRUGGLE EXPERIENCED BY PATTY DAY IN GILLIAN FLYNN’S “DARK PLACES” (2009): A MARXIST FEMINIST THEORY Abstrak Penelitian ini bertujuan untuk menyelidiki jenis-jenis perjuangan perempuan yang dialami oleh Patty Day in Dark Places oleh Gillian Flynn, penggambarannya dalam novel, dan alasan mengapa masalah tersebut digambarkan oleh penulis dalam novelnya. Dalam menganalisis Dark Places, penelitian ini menggunakan teori Marxis-feminis dan teori perjuangan yang disajikan oleh Marsam (2000). Jenis-jenis perjuangan perempuan yang coba ditekankan oleh Gillian Flynn adalah perjuangan dalam ekonomi seperti: kelas sosial, perjuangan kelas, dan akses ke kapasitas finansial. Dengan mengamati latar belakang kehidupan tokoh utama dan hubungan sosial yang memengaruhi tokoh utama dalam melakukan beberapa tindakan perjuangan, dapat disimpulkan bahwa penggambaran perjuangan perempuan dapat dilihat dalam bentuk diskriminasi yang terjadi pada tokoh utama. Dark Places memberikan gambaran yang jelas bahwa perjuangan wanita dalam novel adalah untuk memberi tahu pembaca, terutama pembaca wanita, untuk lebih sadar akan apa yang mungkin mereka alami sebagai istri dan ibu di masa depan. Kata Kunci: perjuangan, diskriminasi, feminisme, teori marxis-feminis, kinnakee Abstract This research aims to investigate the kinds of woman struggle that experienced by Patty Day in Dark Places by Gillian Flynn, its depiction in the novel, and the reason why the issue is depicted by the author in her novel. -

Taylor Muller Honors Thesis

CONTEMPORARY REPRESENTATIONS OF MARRIAGE IN LITERATURE AND POP CULTURE by Taylor Muller Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Departmental Honors in the Department of English Texas Christian University Fort Worth, Texas May 2, 2014 ii CONTEMPORARY REPRESENTATIONS OF MARRIAGE IN LITERATURE AND POP CULTURE Project Approved: Supervising Professor: Ariane Balizet, Ph.D. Department of English Carrie Leverenz, Ph.D. Department of English Sharon Fairchild, Ph.D. Department of Modern Language Studies iii ABSTRACT This research examines the representations of marriage in the novels The Marriage Plot and Gone Girl, reality television shows including Say Yes to the Dress, Four Weddings, and The Bachelor, and social media websites such as Pinterest. The analysis focuses on how these contemporary representations demonstrate normative gender roles, and what claims they make about marriage today. Several patterns emerged when using in particular the theories of Judith Butler and Frances Dolan as a framework for understanding the portrayals of marriage. The depictions of marriage included individuals adopting some sort of role-performance, often gender specific, and reiterated the conflict for power in marriage between the two parties. These were magnified in the dramatization of real life, such as reality television shows, and frequently reiterated traditional understandings of marriage within a modern context. iv TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION...............................................................................................................1 -

—Even on the Bad Days Liking

americangirl.com a smart girl’s guide | a smart girl’s liking herself —even on the bad days liking as a bad day got you LIKING HERSELF LIKING down? Is low self- esteem making you feel herself—even on the bad days blue? In A Smart Girl’s Guide to Liking Herself—Even on the secrets to trusting yourself, being your best the Bad Days, you’ll learn how & never letting the bad days bring you down having high self-confidence can turn a good day into a great day, while having low self-esteem can turn a bad day into a nightmare. You’ll learn tips for trusting yourself, ideas for boosting your self-esteem (or for keeping it up), and ways to feel your best in all kinds of situations. You are perfect just as you are, and this book will help you believe that to be true! Look for these and other bestselling books from American Girl: This book is available as an e-book. ) $12.99 U.S. FNL17-EB1A ™ MADE IN CHINA Discover online games, quizzes, activities, HECHO EN CHINA and more at FABRIQUÉ EN CHINE americangirl.com/play LB_FNL17_Cover.indd 1 6/30/17 9:23 AM Liking Herself —even on the bad days the secrets to trusting yourself, being your best & never letting the bad days bring you down by Dr. Laurie Zelinger illustrated by Jennifer Kalis LB_FNL17_Pages.indd 1 6/29/17 6:02 PM Dear Reader, Growing up can be hard. Lots of things keep changing in your life: your body, your family, your school, and your friends. -

Personality Disorder of Amy Dunne in Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn

PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERSONALITY DISORDER OF AMY DUNNE IN GONE GIRL BY GILLIAN FLYNN AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fullfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By PATRICIA NADIA RAHMA PRATIWI Student Number: 144214075 DEPARTEMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2019 PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PERSONALITY DISORDER OF AMY DUNNE IN GONE GIRL BY GILLIAN FLYNN AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS Presented as Partial Fullfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Sarjana Sastra in English Letters By PATRICIA NADIA RAHMA PRATIWI Student Number: 144214075 DEPARTEMENT OF ENGLISH LETTERS FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY YOGYAKARTA 2019 ii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI GOOD THINGS TAKE TIME vii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI This page is dedicated for: MY FATHER IN HEAVEN, MY LOVELY MOTHER, AND MY BIG SISTER. viii PLAGIAT MERUPAKAN TINDAKAN TIDAK TERPUJI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to express my gratitude towards Jesus Christ for His grace and endless blessings so that I could finish my undergraduate thesis. For so many things that I have faced make me even stronger. Second of all, I would like to say thank you to my thesis advisor, Dr. Ga- briel Fajar Sasmita Aji M.Hum., who patiently help me to finish this undergradu- ate thesis and also always give the positive vibes and the spirit. I would like to thank my co-advisor, Sri Mulyani, Ph,D. -

Osher at JHU Course Catalog Baltimore/Columbia Fall 2021

Osher at JHU COURSE SCHEDULE Baltimore/Columbia Fall 2021 Dedicated to lifelong learning, the Osher at JHU program was created in 1986 with a mission of enhancing the leisure time of semi-retired and retired individuals by providing stimulating learning experiences and the opportunity for new friendships. The Osher at JHU program builds on the rich resources of an internationally renowned university to offer members an array of educational and social opportunities, including the following: • Courses and discussion groups • Access to the university library system • Field trips to cultural events • Preferred participation in university-sponsored events Fall 2021 courses will be offered online via Zoom. When in-person programs resume, they will be offered at two convenient locations. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, courses are conducted at the Grace United Methodist Church, 5407 North Charles Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21210. On Mondays and Wednesdays, courses are conducted at the First Presbyterian Church of Howard County, 9325 Presbyterian Circle, Columbia, MD 21045. For additional information on membership, please call the program’s administrative office at 607-208-8693. Osher at JHU Home Page COLUMBIA Monday MORNING SESSION From Tribes to Monarchy: The Book of Judges The Book of Judges, the seventh (out of 24) book of the Hebrew Bible, describes the transition time between the conquest of Canaan (the Book of Joshua) and the beginning of monarchy (in the early Book of I Samuel). In the interim, warriors who were called Judges emerged as the leaders when needed. In the book of Judges, one finds the first attempt to explain history through Deuteronomist glasses, and therefore this and the rest of the history books are assumed to be written by “the Deuteronomic Historians.” Some stories are very short while others are long with many details. -

Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Say It Suicide Squad OST Nothing Has Changed: the Best of 1 the Chainsmokers Feat

05 September 2016 CHART #2050 Top 40 Singles Top 40 Albums Closer Say It Suicide Squad OST Nothing Has Changed: The Best Of 1 The Chainsmokers feat. Halsey 21 Flume feat. Tove Lo 1 Various 21 David Bowie Last week 1 / 5 weeks Gold / Disruptor/SonyMusic Last week 18 / 19 weeks Platinum / FutureClassic/Univers... Last week 2 / 4 weeks Atlantic/Warner Last week 28 / 32 weeks Platinum / Parlophone/Warner Cold Water Ride 25 All Over The World: The Best Of 2 Major Lazer feat. Justin Bieber And... 22 Twenty One Pilots 2 Adele 22 ELO Last week 2 / 6 weeks Gold / Because/Warner Last week 20 / 16 weeks Gold / FueledByRamen/Warner Last week 3 / 41 weeks Platinum x7 / XL/Rhythm Last week 22 / 20 weeks Gold / SonyMusic Let Me Love You This Girl Blonde A/B 3 DJ Snake feat. Justin Bieber 23 Kungs And Cookin' On 3 Burners 3 Frank Ocean 23 Kaleo Last week 3 / 4 weeks Interscope/Universal Last week 23 / 9 weeks KungsMusic/Universal Last week 1 / 2 weeks BoysDon'tCry Last week 15 / 4 weeks Elektra/Warner Heathens Cheap Thrills Poi E: The Story Of Our Song Endless Highway 4 Twenty One Pilots 24 Sia 4 Various 24 Phil Doublet Last week 4 / 11 weeks Gold / Atlantic/Warner Last week 22 / 28 weeks Platinum x2 / Inertia/Rhythm Last week 6 / 4 weeks SonyMusic Last week - / 1 weeks PhilDoublet Sucker For Pain Final Song Encore: Movie Partners Sing Broadw... Revival 5 Lil Wayne, Wiz Khalifa And Imagine... 25 M0 5 Barbra Streisand 25 Selena Gomez Last week 7 / 4 weeks Atlantic/Warner Last week 21 / 7 weeks SonyMusic Last week - / 1 weeks Columbia/SonyMusic Last week 14 / 16 weeks Interscope/Universal Don't Worry Bout It Cool Girl Blurryface Beauty Behind The Madness 6 Kings 26 Tove Lo 6 Twenty One Pilots 26 The Weeknd Last week 5 / 8 weeks Gold / ArchAngel/Warner Last week 29 / 3 weeks Universal Last week 5 / 34 weeks Gold / FueledByRamen/Warner Last week 20 / 40 weeks Republic/Universal One Dance Needed Me Views Cloud Nine 7 Drake feat.