Remun Language Use and Maintenance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

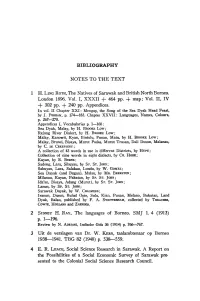

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES to the TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, the Natives

BIBLIOGRAPHY NOTES TO THE TEXT 1 H. LING ROTH, The Natives of Sarawak and British North Borneo. London 18%. Vol. I, XXXII + 464 pp. + map; Vol. II, IV + 302 pp. + 240 pp. Appendices. In vol. II Chapter XXI: Mengap, the Song of the Sea Dyak Head Feast, by J. PERHAM, p. 174-183. Chapter XXVII: Languages, Names, Colours, p.267-278. Appendices I, Vocabularies p. 1-160: Sea Dyak, Malay, by H. BROOKE Low; Rejang River Dialect, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Kanowit, Kyan, Bintulu, Punan, Matu, by H. BROOKE Low; Malay, Brunei, Bisaya, Murut Padas, Murut Trusan, Dali Dusun, Malanau, by C. DE CRESPIGNY; A collection of 43 words in use in different Districts, by HUPE; Collection of nine words in eight dialects, by CH. HOSE; Kayan, by R. BURNS; Sadong, Lara, Sibuyau, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sabuyau, Lara, Salakau, Lundu, by W. GoMEZ; Sea Dayak (and Bugau), Malau, by MR. BRERETON; Milanau, Kayan, Pakatan, by SP. ST. JOHN; Ida'an, Bisaya, Adang (Murut), by SP. ST. JOlIN; Lanun, by SP. ST. JOHN; Sarawak Dayak, by W. CHALMERS; Iranun, Dusun, Bulud Opie, Sulu, Kian, Punan, Melano, Bukutan, Land Dyak, Balau, published by F. A. SWETTENHAM, collected by TREACHER, COWIE, HOLLAND and ZAENDER. 2 SIDNEY H. RAY, The languages of Borneo. SMJ 1. 4 (1913) p.1-1%. Review by N. ADRIANI, Indische Gids 36 (1914) p. 766-767. 3 Uit de verslagen van Dr. W. KERN, taalambtenaar op Borneo 1938-1941. TBG 82 (1948) p. 538---559. 4 E. R. LEACH, Social Science Research in Sarawak. A Report on the Possibilities of a Social Economic Survey of Sarawak pre sented to the Colonial Social Science Research Council. -

Social Variation of Malay Language in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia: a Study on Accent, Identity and Integration

GEMA Online Journal of Language Studies 63 Volume 9(1) 2009 Social Variation Of Malay Language In Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia: A Study On Accent, Identity And Integration Idris Aman [email protected] Rosniah Mustaffa [email protected] Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Abstract Language variation is conveyed through its regional or social dimension. In line with that proposition, this paper discusses the social variation of Malay language spoken in Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia focussing on their accents. As part of the Malay language society, the Malays of Kuching have their own accent which is different from other Malay accents or the standard national accent. This paper analyzes the status of national standard accent and non-standard accent among the Malay informants in the city of Kuching. The discussion is based on a sociological urban dialectology research. For the analysis, five phonological variables are chosen. They are open-ended vowels (a), such as kita ‘we’ , close-ended (i), such bilik ‘room’, close-ended (u), such as masuk ‘enter’, initial (r) or (r) 1, such as rumah ‘home’, and final (r) or (r) 2, such as pasar ‘market’ . Issues on accents are studied through four different degree of formality of speech styles, namely reading word list style (WLS), reading passage style (PS), conversational style (CS) and story-telling style (STS). Three social contextual variables - socio-economic status, sex, and age groups of the informants will be considered in the analysis. The use of national standard accent compared with the non-standard accent will be linked to issues of identity and integration. -

(Myrtaceae) from Borneo

Gardens' Bulletin Singapore 57 (2005) 269-278 269 New Tristaniopsis Peter G.Wilson & J.T.Waterh. (Myrtaceae) From Borneo P. S. ASHTON Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University, 22 Divinity Avenue Cambridge MA 02138, U.S.A. and Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, Richmond, Surrey, TW9 3AB, U.K. Abstract Three new species, Tristaniopsis kinabaluensis P.S.Ashton, T. microcmpa P.S.Ashton and T. wbiginosa S.Teo ex P.S.Ashton, and three new subspecies, Tristaniopsis kinabaluensis ssp. silamensis P.S.Ashton, T. merguensis ssp. tavaiensis P.S.Ashton and T. whitiana ssp. monostemon P.S.Aston, are described from northern Borneo, in preparation for a treatment of the Myrtaceae for the Tree Flora of Sabah and Sarawak. Introduction Species definition in Tristaniopsis Peter G.Wilson & J.T.Waterh. (formerly Tristania R. Br.) has proven to be even more difficult in Borneo than among the notorious and much larger myrtaceous genus Syzygium Gaertn. Leaf size and shape is variable. The number of stamens, which are clustered opposite the petals, is characteristic of each species but, although at most 10 per cluster, may vary in exceptional cases. Here, we adopt a conservative species concept, awaiting regional monographic and phylogenetic research. Eventually, and with further flowering collections, some at least of the infrapecific taxa described here may be raised to species rank. All specimens examined have been at the Kew herbarium unless otherwise stated. 1. Tristaniopsis kinabaluensis P.S.Ashton, sp. llOV. T. m.erguensis affinis, foliis minoribus basim versus subsessilibus attenuatis vel anguste obtusis baud auriculatis, subtus hebete glaucescentibus, staminibus 3(-5) in fasciculis, fructibus ad 5 x 4 mm minoribus facile 270 Card. -

Learn Thai Language in Malaysia

Learn thai language in malaysia Continue Learning in Japan - Shinjuku Japan Language Research Institute in Japan Briefing Workshop is back. This time we are with Shinjuku of the Japanese Language Institute (SNG) to give a briefing for our students, on learning Japanese in Japan.You will not only learn the language, but you will ... Or nearby, the Thailand- Malaysia border. Almost one million Thai Muslims live in this subregion, which is a belief, and learn how, to grow other (besides rice) crops for which there is a good market; Thai, this term literally means visitor, ASEAN identity, are we there yet? Poll by Thai Tertiary Students ' Sociolinguistic. Views on the ASEAN community. Nussara Waddsorn. The Assumption University usually introduces and offers as a mandatory optional or free optional foreign language course in the state-higher Japanese, German, Spanish and Thai languages of Malaysia. In what part students find it easy or difficult to learn, taking Mandarin READING HABITS AND ATTITUDES OF THAI L2 STUDENTS from MICHAEL JOHN STRAUSS, presented partly to meet the requirements for the degree MASTER OF ARTS (TESOL) I was able to learn Thai with Sukothai, where you can learn a lot about the deep history of Thailand and culture. Be sure to read the guide and learn a little about the story before you go. Also consider visiting neighboring countries like Cambodia, Vietnam and Malaysia. Air LANGUAGE: Thai, English, Bangkok TYPE OF GOVERNMENT: Constitutional Monarchy CURRENCY: Bath (THB) TIME ZONE: GMT No 7 Thailand invites you to escape into a world of exotic enchantment and excitement, from the Malaysian peninsula. -

Language Use and Attitudes As Indicators of Subjective Vitality: the Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia

Vol. 15 (2021), pp. 190–218 http://nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc http://hdl.handle.net/10125/24973 Revised Version Received: 1 Dec 2020 Language use and attitudes as indicators of subjective vitality: The Iban of Sarawak, Malaysia Su-Hie Ting Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Andyson Tinggang Universiti Malaysia Sarawak Lilly Metom Universiti Teknologi of MARA The study examined the subjective ethnolinguistic vitality of an Iban community in Sarawak, Malaysia based on their language use and attitudes. A survey of 200 respondents in the Song district was conducted. To determine the objective eth- nolinguistic vitality, a structural analysis was performed on their sociolinguistic backgrounds. The results show the Iban language dominates in family, friend- ship, transactions, religious, employment, and education domains. The language use patterns show functional differentiation into the Iban language as the “low language” and Malay as the “high language”. The respondents have positive at- titudes towards the Iban language. The dimensions of language attitudes that are strongly positive are use of the Iban language, Iban identity, and intergenera- tional transmission of the Iban language. The marginally positive dimensions are instrumental use of the Iban language, social status of Iban speakers, and prestige value of the Iban language. Inferential statistical tests show that language atti- tudes are influenced by education level. However, language attitudes and useof the Iban language are not significantly correlated. By viewing language use and attitudes from the perspective of ethnolinguistic vitality, this study has revealed that a numerically dominant group assumed to be safe from language shift has only medium vitality, based on both objective and subjective evaluation. -

REVIEWING LEXICOLOGY of the NUSANTARA LANGUAGE Mohd Yusop Sharifudin Universiti Putra Malaysia Email

Journal of Malay Islamic Studies Vol. 2 No. 1 June 2018 REVIEWING LEXICOLOGY OF THE NUSANTARA LANGUAGE Mohd Yusop Sharifudin Universiti Putra Malaysia Email: [email protected] Abstract The strength of a language is its ability to reveal all human behaviour and progress of civilization. Language should be ready for use at all times and in any human activity and must be able to grow together with all forms of discipline and knowledge. Languages that are not dynamic over time will become obsolete, archaic and finally extinct. Accordingly, the effort to develop and create a civilisation needs to take into account also the effort to expand its language as the medium of instruction. The most basic language development in this regard was to look for vocabulary that could potentially be taken to develope a dynamic language. This paper shows the potential and the wealth of lexical resources in building the Nusantara language to become a world language. Keywords: Lexicology, Nusantara Language Introduction Language is an important means for humans to communicate and build interaction. Language is basically a means of communication within community members. Communication takes place not only verbally, but also in writing (Sirbu 2015, 405). language is also a tool that shows the level of civilization in humans (Holtgraves et al. 2014, 230). In order to play an important role as a means of developing civilization, language must continue to develop dynamically over time and enriched according to the needs and development of civilization. Likewise the case with Nusantara Malay language. This paper aims to describe how to develop Nusantara Malay language through the development of various Malay vocabularies. -

Laporan Keputusan Akhir Dewan Undangan Negeri Bagi Negeri Sarawak Tahun 2016

LAPORAN KEPUTUSAN AKHIR DEWAN UNDANGAN NEGERI BAGI NEGERI SARAWAK TAHUN 2016 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.192-MAS GADING N.01 - OPAR RANUM ANAK MINA BN 3,665 MNG NIPONI ANAK UNDEK BEBAS 1,583 PATRICK ANEK UREN PBDSB 524 HD FRANCIS TERON KADAP ANAK NOYET PKR 1,549 JUMLAH PEMILIH : 9,714 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 57 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 7,419 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 41 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 76.40% MAJORITI : 2,082 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.192-MAS GADING N.02 - TASIK BIRU MORDI ANAK BIMOL DAP 5,634 HENRY @ HARRY ANAK JINEP BN 6,922 MNG JUMLAH PEMILIH : 17,041 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 197 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 12,797 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 44 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 75.10% MAJORITI : 1,288 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.03 - TANJONG DATU ADENAN BIN SATEM BN 6,360 MNG JAZOLKIPLI BIN NUMAN PKR 468 HD JUMLAH PEMILIH : 9,899 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 77 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 6,936 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 31 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 70.10% MAJORITI : 5,892 PRU DUN Sarawak Ke-11 1 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.04 - PANTAI DAMAI ABDUL RAHMAN BIN JUNAIDI BN 10,918 MNG ZAINAL ABIDIN BIN YET PAS 1,658 JUMLAH PEMILIH : 18,409 KERTAS UNDI DITOLAK : 221 KERTAS UNDI DIKELUARKAN : 12,851 KERTAS UNDI TIDAK DIKEMBALIKAN : 54 PERATUSAN PENGUNDIAN : 69.80% MAJORITI : 9,260 BAHAGIAN PILIHAN RAYA NAMA CALON PARTI BILANGAN UNDI STATUS P.193-SANTUBONG N.05 - DEMAK LAUT HAZLAND -

Languages of Malaysia (Sarawak)

Ethnologue report for Malaysia (Sarawak) Page 1 of 9 Languages of Malaysia (Sarawak) Malaysia (Sarawak). 1,294,000 (1979). Information mainly from A. A. Cense and E. M. Uhlenbeck 1958; R. Blust 1974; P. Sercombe 1997. The number of languages listed for Malaysia (Sarawak) is 47. Of those, 46 are living languages and 1 is extinct. Living languages Balau [blg] 5,000 (1981 Wurm and Hattori). Southwest Sarawak, southeast of Simunjan. Alternate names: Bala'u. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Malayic, Malayic-Dayak, Ibanic More information. Berawan [lod] 870 (1981 Wurm and Hattori). Tutoh and Baram rivers in the north. Dialects: Batu Bla (Batu Belah), Long Pata, Long Jegan, West Berawan, Long Terawan. It may be two languages: West Berawan and Long Terawan, versus East-Central Berawang: Batu Belah, Long Teru, and Long Jegan (Blust 1974). Classification: Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Northwest, North Sarawakan, Berawan-Lower Baram, Berawan More information. Biatah [bth] 21,219 in Malaysia (2000 WCD). Population total all countries: 29,703. Sarawak, 1st Division, Kuching District, 10 villages. Also spoken in Indonesia (Kalimantan). Alternate names: Kuap, Quop, Bikuab, Sentah. Dialects: Siburan, Stang (Sitaang, Bisitaang), Tibia. Speakers cannot understand Bukar Sadong, Silakau, or Bidayuh from Indonesia. Lexical similarity 71% with Singgi. Classification: Austronesian, Malayo-Polynesian, Land Dayak More information. Bintulu [bny] 4,200 (1981 Wurm and Hattori). Northeast coast around Sibuti, west of Niah, around Bintulu, and two enclaves west. Dialects: Could also be classified as a Baram-Tinjar Subgroup or as an isolate within the Rejang-Baram Group. Blust classifies as an isolate with North Sarawakan. Not close to other languages. -

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 1 JAWATANKUASA

Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 JAWATANKUASA PENGURUSAN BENCANA NEGERI SARAWAK KENYATAAN MEDIA (06 OGOS 2021) 1. LAPORAN HARIAN A. JUMLAH KES COVID-19 JUMLAH KES BAHARU COVID-19 652 JUMLAH KUMULATIF KES COVID-19 80,174 B. PECAHAN KES COVID-19 BAHARU MENGIKUT DAERAH BILANGAN BILANGAN BIL. DAERAH BIL. DAERAH KES KES 1 Kuching 231 21 Betong 1 2 Simunjan 84 22 Meradong 1 3 Serian 65 23 Tebedu 1 4 Mukah 55 24 Kabong 0 5 Miri 34 25 Sebauh 0 6 Sibu 31 26 Dalat 0 7 Samarahan 22 27 Kapit 0 8 Bintulu 21 28 Tanjung Manis 0 9 Bau 20 29 Julau 0 10 Kanowit 18 30 Pakan 0 11 Tatau 17 31 Lawas 0 12 Sri Aman 12 32 Pusa 0 13 Selangau 12 33 Song 0 14 Lundu 11 34 Daro 0 15 Telang Usan 6 35 Belaga 0 16 Saratok 2 36 Marudi 0 17 Sarikei 2 37 Limbang 0 18 Subis 2 38 Bukit Mabong 0 19 Beluru 2 39 Lubok Antu 0 20 Asajaya 2 40 Matu 0 1 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 C. RINGKASAN KES COVID-19 BAHARU TIDAK BILANGAN BIL. RINGKASAN SARINGAN BERGEJALA BERGEJALA KES Individu yang mempunyai kontak kepada kes 1 55 255 310 positif COVID-19. 2 Individu dalam kluster aktif sedia ada. 3 118 121 3 Saringan Individu bergejala di fasiliti kesihatan. 37 0 37 4 Lain-lain saringan di fasiliti kesihatan. 4 180 184 JUMLAH 99 553 652 D. KES KEMATIAN COVID-19 BAHARU: TIADA 2 Kenyataan Media JPBN Bil 218/2021 E. -

Language Vitality of the Sihan Community in Sarawak, Malaysia

KEMANUSIAAN Vol. 19, No. 1, (2012), 59–86 Language Vitality of the Sihan Community in Sarawak, Malaysia NORIAH MOHAMED NOR HASHIMAH HASHIM Universiti Sains Malaysia, Pulau Pinang, Malaysia [email protected] [email protected] Abstract. This paper discusses the language vitality of the Sihan or Sian community in Sarawak. Vitality of language refers to the ability of a language to live or grow. The language vitality of the Sihans was investigated using a field survey, observation and interviews. The output of the field survey was analysed using the nine criteria of language vitality, outlined in the UNESCO Expert Meeting in March, 2003 (Lewis 2006, 4; Brenzinger et al. 2003). The nine criteria include intergenerational language transmission, absolute number of speakers, proportion of speakers within the total population, trends in existing language domains, response to new domains and media, materials for language education and literacy, language attitudes and policies, community members' attitudes toward their own language and the amount and quality of documentation (Brenzinger et al. 2003, 7–17). The data from the survey were supported by the data obtained from observation and interviews. The findings of the study reveals that the Sihan language is under threat as it does not fulfil UNESCO's nine criteria of language vitality. Keywords and phrases: language vitality, ethnolinguistic vitality, Sihan or Sian language, endangered language, language domains Introduction: The Sihan or Sian The Sihan people are indigenous to Sarawak, a Malaysian state on the island of Borneo. They belong to the Austronesian group of speakers and are similar in appearance to other indigenous groups in Sarawak. -

Revisiting Community Bidayuh Empowerment Using Abductive Research Strategy

Asian Social Science; Vol. 9, No. 8; 2013 ISSN 1911-2017 E-ISSN 1911-2025 Published by Canadian Center of Science and Education Revisiting Community Bidayuh Empowerment Using Abductive Research Strategy N. Lyndon1, A. C. Er1, S. Selvadurai1, M. S. Sarmila1, M. J. Fuad1, R. Zaimah1, Azimah A. M.1, Suhana S.1, A. Mohd Nor Shahizan2, Ali Salman2 & Rose Amnah Abd Rauf3 1 School of Social, Development and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia 2 School of Media and Communication Studies, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia 3 Faculty of Education, Universiti Malaya (UM), Malaysia Correspondence: N. Lyndon, School of Social, Development and Environmental Studies, Faculty of Social Sciences and Humanities, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, Malaysia. Tel: 60-3-8921-4212. E-mail: [email protected] Received: December 19, 2012 Accepted: March 29, 2013 Online Published: April 25, 2013 doi:10.5539/ass.v9n8p64 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ass.v9n8p64 This research was supported by Centre for Research and Instrument Management, under the research university grant, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia: UKM-GGPM-PLW-018-2011 Abstract Previous studies shows that the failure of community development in Malaysia always related with two aspects such as the emphasis on top-down approach which is the centralization of power without the active participation of community members and also a limited understanding of the needs and aspirations of the local people. Therefore the main objective of this study is to understand the meaning of empowerment from the world-view of Bidayuh community itself. This study using abductive research strategy and a phenomenology research paradigm which is based on idealist ontology and constructionist epistemology. -

The Case of the Bidayuh Language in Sarawak

Journal of Modern Languages Vol. 30, (2020) https://doi.org/10.22452/jml.vol30no1.3 Examining Language Development and Revitalisation Initiatives: The Case of the Bidayuh Language in Sarawak Patricia Nora Riget* [email protected] Universiti Malaya, Malaysia Yvonne Michelle Campbell [email protected] Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, Malaysia Abstract This article examines development and revitalisation initiatives for the Bidayuh language, spoken in Sarawak, East Malaysia. Bidayuh has six main variants which are not mutually intelligible. In addition, it is mainly used in rural settings and is not the main language of choice in mixed marriages. Moreover, Bidayuh did not have a standardised orthography until 2003. These factors have affected the development of the language, which is to be contrasted with the Iban language, spoken by the main ethnic group in Sarawak, which is currently offered in primary schools as Pupil’s Own Language (POL) and as an elective subject in the secondary school Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) examination. The focus of this article is the language development and revitalization initiatives undertaken by various stakeholders between 1963 (the year of the formation of the Federation of Malaysia) and today. Special attention will be paid to the outcome of the Multilingual Education (MLE) project, which is an extension of the Bidayuh Language Development Project (BLDP) initiated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in Asia, and undertaken by the Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) and the Dayak Bidayuh National Association (DBNA). Interviews with representatives of the 101 Examining Language Development and Revitalisation Initiatives community were conducted to discover their perceptions towards these initiatives, and to identify factors that might contribute to their success and/or failure.