Antequera, Málaga

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Antequera, Un Paisaje Cultural Para El Turismo Literario

GRADUADO/A EN TURISMO TRABAJO FIN DE GRADO Antequera, un paisaje cultural para el turismo literario Realizado por: Tamara García Carmona Fdo.: Dirigido por: María Aurora Arjones Fernández Vº Bueno del tutor Fdo.: MÁLAGA, Junio 2016 TÍTULO: Antequera, un paisaje cultural para el turismo literario PALABRAS CLAVE: Turismo literario, escritores, espacios turístico- literarios, rutas literarias, posibilidad turística, Antequera. RESUMEN: El turismo literario define una modalidad de turismo cultural plenamente establecida en la UNESCO a través de la Red de Ciudad de la Literatura; con amplio bagaje en Londres o Paris; de reciente incorporación en la oferta turística de España, donde destaca el paisaje cultural de Barcelona; y prácticamente inédito para el mercado turístico de la comunidad autónoma de Andalucía. El paisaje cultural de Antequera ofrece un recurso excepcional para esta reciente modalidad turística, ya que a priori los hitos del paisaje cultural de Antequera suponen un referente para los turistas consumidores de cultura literaria. Es decir, los atractivos literarios del paisaje cultural de Antequera coinciden con los recursos más visitados y atractivos de esta ciudad para el turismo cultural en general. Es más, Antequera ya dispone de dos infraestructuras que darían cobertura al turismo literario, estas son: la Biblioteca de San Zoilo y el Archivo Histórico. Los Dólmenes de Antequera y la Real Colegiata de Santa María, son algunos de los lugares que potenciamos como recursos culturales para el turismo literario. ÍNDICE Capítulo 1 Introducción......................................................................... 1 Capítulo 2 Aproximación al turismo literario.......................................... 3 2.1. Conceptualización de turismo literario. ....................................... 3 2.1.1. Motivación y perfil del turista. ................................................ 3 2.1.2. -

Túneles De Abdalajís

Túneles de Abdalajís ÍNDICE DE CONTENIDOS 1.- Introducción 2.- Tramo Gobantes – Túnel de Abdalajís Este 3.- Ejecución de los túneles Proceso de construcción Galerías de Seguridad 4.- Tuneladoras Partes de la tuneladora Funcionamiento Instalaciones auxiliares Principales características de las tuneladoras 5.- Revestimiento interior 6.- Compromiso Medioambiental Protección del Sistema Hidrológico Otras medidas adoptadas 1 1.- Introducción La construcción de la línea de Alta Velocidad Córdoba-Málaga se inscribe en el corredor de Andalucía, que conectará a través de la línea Madrid-Córdoba- Sevilla, con Málaga, Jaén, Granada, Cádiz y Huelva. Esta línea cuenta con una longitud total de 155 kilómetros (desde el enlace con la línea de Alta Velocidad Sevilla-Madrid en el término municipal cordobés de Almodóvar del Río, hasta Málaga capital) y su construcción se dividió en un total de 22 tramos, con un presupuesto total de 2.100 millones de euros. La línea se construye en doble vía electrificada de ancho U.I.C. (internacional) preparada para desarrollar velocidades máximas de 350 kilómetros por hora. A efectos de su paulatina puesta en servicio, su trazado puede dividirse en tres grandes tramos: • Almodóvar del Río-Antequera, de 100 kilómetros. • Antequera-Arroyo de las Cañas, de 49 kilómetros. • Arroyo de las Cañas-Málaga, de 6 kilómetros. 2 Por lo que respecta al tramo Antequera-Arroyo de las Cañas, en él se sitúan las mayores obras de ingeniería, tanto la mayor parte de los 19 kilómetros de túneles como de viaductos. Destaca en este tramo la construcción del doble túnel de Abdalajís, que con más de 7 kilómetros de longitud, es el mayor construido en Andalucía. -

Costa Del Golf Malaga

COSTA DEL SOL COSTA DEL GOLF COSTA DEL GOLF COSTA DEL SOL - COSTA DEL GOLF COSTA DEL GOLF Welcome to the Costa del Golf With more than 70 world-class golf courses, the Costa del Sol has been dubbed the Costa del Golf, a prime destination for sports holidays. Situated midway between the sea and the mountains, with 325 days of sun a year and an average annual temperature in the 20°Cs, the Costa del Sol promises perfect playing conditions all year round. And as if that weren’t enough, there’s plenty of culture to soak up, as well as leisure activities and entertainment to pleasantly while away the hours. Not to mention the balmy beaches, stunning natural landscapes and excellent connections by air (Malaga international airport is the third largest in Spain), land (dual carriageways, motorways, high speed trains) and sea (over 11 marinas). All coming together to make the Costa del Sol, also known as the Costa del Golf, the favourite golfing destination in Europe. COSTA DEL SOL - COSTA DEL GOLF COSTA DEL GOLF A round of golf in stunning surroundings The diverse range of course designs will make you want to come back year after year so you can discover more and more new courses. From pitch and putt to the most demanding holes, there is a seemingly endless array of golf courses to choose from. Diversity is one of the defining characteristics of the Costa del Golf; and there really is something for everyone. The golf courses regularly organise classes and championships for men and women of all levels. -

Energía En La UE: Bruselas Tiene Un Plan ■ El Paraje Natural De El Torcal Se Apunta a La Climatización Solar

Número 55 Marzo 2007 3 euros Vino de La Mancha Un caldo con muchas energías ■ Energía en la UE: Bruselas tiene un plan ■ El Paraje Natural de El Torcal se apunta a la climatización solar ■ La energía del viento sigue ganando adeptos en el mundo ■ Medio millar de viviendas de ■ Hasta Bush se cree Oviedo se calientan con biomasa el último informe del IPCC ■ Motor: la "tetera" de Honda Energías w w w . e n e r g ii a s - r e nro v aeb ll e s .nc o m ovables ■ panorama La actualidad en breves 8 Nueva política energética en la UE, Bruselas tiene un plan 13 Los europeos y la energía. “Sí, algo se de eso…” 20 EnerAgen 28 ■ eólica La energía del viento sigue ganando adeptos en el mundo 30 Elecnor se convierte en líder en Iberoamérica 34 ■ solar fotovoltáica Células solares con más del 40% de eficiencia ¿Quién dijo que eran ineficientes? 38 La célula multicapa 43 ■ solar térmica El Paraje Natural de El Torcal predica con el ejemplo 46 Número 55 ■ entrevista Marzo 2007 Xabier Viteri, director de Energías Renovables de Iberdrola 50 ■ biomasa Calderas de biomasa para quince bloques de apartamentos en Oviedo 54 Bioelectricidad, un millón de hectáreas en barbecho 58 ■ biocarburantes Vino de La Mancha, un caldo con mucha energía 62 ■ energías del mar Pisys, tecnología española para producir energía con las olas 66 ■ empresas HAWI Energías renovables. Echar a andar con buen pie 72 ■ CO2 Último informe del Panel Intergubernamental sobre Cambio Climático (IPCC). Hasta Bush se lo cree 76 ■ motor Honda FCX, la tetera de Honda 80 Se anuncian en éste número: ■ ADWORK........................... -

Downloads/Capture/Index.Html

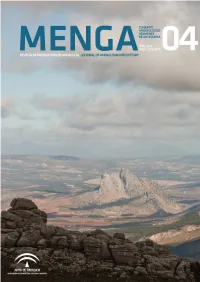

MENGA 04 REVISTA DE PREHISTORIA DE ANDALUCÍA JOURNAL OF ANDALUSIAN PREHISTORY Publicación anual Año 3 // Número 04 // 2013 JUNTA DE ANDALUCÍA. CONSEJERÍA DE EDUCACIÓN, CULTURA Y DEPORTE Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera ISSN 2172-6175 Depósito Legal: SE 8812-2011 Distribución nacional e internacional: 200 ejemplares Menga es una publicación anual del Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera (Consejería de Educación, Cultura y Deporte de la Junta de Andalucía). Su objetivo es la difusión internacional de trabajos de investigación científicos de calidad relativos a la Prehistoria de Andalucía. Menga se organiza en cuatro secciones: Dossier, Estudios, Crónica y Recensio- nes. La sección de Dossier aborda de forma monográfica un tema de inves- tigación de actualidad. La segunda sección tiene un propósito más general y está integrada por trabajos de temática más heterogénea. La tercera sección denominada como Crónica recogerá las actuaciones realizadas por el Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera en la anualidad anterior. La última sección incluye reseñas de libros y otros eventos (tales como exposiciones científicas, seminarios, congresos, etc.). Menga está abierta a trabajos inéditos y no presentados para publicación en otras revistas. Todos los manuscritos originales recibidos serán sometidos a un proceso de evaluación externa y anónima por pares como paso previo a su aceptación para publicación. Excepcionalmente, el Consejo Editorial podrá aceptar la publicación de traducciones al castellano y al inglés de trabajos ya publicados por causa de su interés y/o por la dificultad de acceso a sus contenidos. Menga is a yearly journal published by the Dolmens of Antequera Archaeological Site (the Andalusian Regional Government Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport). -

Jak Přežít Antropologie Bydlení Pohled Do Minulosti Počátky Lovci

001_052_Strecha 15.8.2006 7:45 Stránka 7 Obsah Předmluva 11 KAPITOLA PRVNÍ Jak přežít Antropologie bydlení 13 Člověk a podnebí 13 Stavební materiál a jeho zpracování 15 Tady zůstaneme. Volba tábořiště 24 Diktát ekonomie 26 Sociální vztahy, nadpřirozený svět 30 KAPITOLA DRUHÁ Pohled do minulosti Počátky 33 Kořeny architektury 33 Nejstarší evropské nálezy 39 Fenomén ohně 47 Stavěli si neandertálci obydlí? 48 Lovci mladého paleolitu 53 Dolní Věstonice, naleziště unikátních objevů a inovací v gravettienu 54 Vigne Brun 59 Rusko a Ukrajina 64 Překvapivé nálezy z Jižní Ameriky 88 Antropologický pohled 90 Magdalénští lovci sobů 97 Poslední lovci, první zemědělci 105 Mezolit 105 Západní Sibiř 105 Lepenski Vir 107 7 001_052_Strecha 15.8.2006 7:45 Stránka 8 Mt. Sandel 110 Příchod neolitu a Sahara 113 Kamenná architektura Sahary 115 Blízký východ 124 Antropologický pohled 131 Nejstarší neolit 134 Mladý mezolit a počátky neolitu v severní Evropě 136 Obydlí konce doby kamenné 141 Dlouhé domy starého neolitu střední Evropy 141 Antropologický pohled 151 Neolitické domy z jihozápadní Francie 156 Staroneolitické sídliště Darian 159 Domy tripolské kultury 160 Iluze „nákolních“ staveb 165 Středoevropský latén a konec pravěku 171 Kultovní a monumentální architektura 177 Rondely 177 Megality 181 Dolmeny 184 Barnenez 191 Newgrange 198 Gavrinis 205 Saharské a kavkazské dolomeny 210 Menhiry 214 Carnac 217 Černovaja 218 Stonehenge 221 Středomoří 226 Odkaz pravěku 243 KAPITOLA TŘETÍ Mizející svět Poslední lovci-sběrači 245 Dobytí severu 245 Paleoeskymáci 245 Fjord -

Parte a Nombre DNI Núm. Id Investig A.1. Sit Organis Dpto. / C Direcció Teléfon Categor Espec. Palabra A.2. Fo Li Lic. Filo D

Fecha del CVA 2020 Parte A. DATOS PERSONALES Nombre y Apellidos ARTURO RUIZ RODRIGUEZ DNI Edad Núm. identificación del Researcher ID investiggador Scopus Author ID Código ORCID A.1. Situación profesional actual Organismo Universidad de Jaén Dpto. / Centro Instituto Universitario de Investigación en Arqueoología Iberica Dirección Edif. C6 Campus Las Lagunillas CP 23071 Jaén España Teléfono 683750016 Correo electrónico arruiz ujaen.es Categoría profesional Catedrático Universidad. Area Prehistoria Fecha inicio 1991 Espec. cód. UNESCO Palabras clave A.2. Formación académica (título, institución, fecha) Liicenciatura/Grado/Doctorado Universidad Año Lic. Filosofía y Letras. Geografía e Historia Univ. Granada 1973 Doctor Historia Univ. Granada 1978 A.3. Indicadores generales de calidad de la producción científica -Seis Tramos de Investigación. El último concedido en 2010. -Tesis dirigidas: 13. La ultima en 2019 - Publicaciones en Congresos, Revistas y Editoriales de primer nivel: Ostraka (Perugia), EPOCH Publication, Archivo Español de Arqueología (Madrid), Roman Frontiers Studies, Oxbow Books (Oxford), Routledge studies in archaeology (New York) Quasar(Roma), Hermann (Paris), Bretschneider (Roma), Madrider Mitteilungen (Mainz) Cambridge University Press. Papers of the EAA, Barker and Lloyd, British School at Rome, Studia Celtica (Wales), Complutum, Antiquity, Quaternary Internaational, etc Parte B. RESUMEN LIBRE DEL CURRÍCCULUM Desde 1974 trabajo en el estudio del territorio ibero en el Alto valle del rio Guadalquivir (SE de la Península Ibérica) en el análisis del poblamiento y su desarrollo en función de las formas políticas que formula la aristocracia desde el s. VII al I a.n.e. En ese marco el proyecto de trabajo ha analizado la cconstrucción de los linajes gentilicios clientelares y su evolución hacia formas de dependencia aristocratica y su relación con la aparición del oppidum. -

Discover the Dolmens of Antequera Right Next to One Stunning Parador

Culture & History - Discovering Spain Andalusia - archaeological remains - archeaological site - historic location - History - holiday destinations - holiday in Spain - luxury hotel - Málaga - Parador Antequera - Paradores in Spain - Southern Spain - Spain - Spanish heritage - Spanish history - Torcal de Antequera - World Heritage Site Discover the Dolmens of Antequera right next to one stunning Parador Thursday, 4 August, 2016 Paradores Parador de Antequera Do you like architecture and history? Do you want to get to know the origins of it? Then you cannot miss a visit to the archaeological complex of the Dolmens of Antequera, built many years ago and declared a World Heritage site on 2016. This incredible place is located only 3km away from the beautiful and modern Parador de Antequera and is definitely a must visit stop in Antequera. The complex is also referred to as the megalithic necropolis of Antequera. The dolmens are built with big rocks that form a type of room with ceiling and walls. There are 3 dolmens in the archaeological complex of the dolmens of Antequera, the Dolmen of Menga, the Dolmen of Viera and the Dolmen of El Romeral. The Dolmen of Menga is the oldest and probably most important one. Is oriented towards the Peña de los Enamorados, a mountain with the shape of the face of a woman. The Dolmen of Viera is oriented towards the sunrise and is located in the first enclosure right next to the Dolmen of El Romeral, in the Campo de los Túmulos. The first stop when visiting this historic wonder is the Center of Reception of the complex, where you can get information and get to know the history and construction of the dolmens before starting the tour. -

Los Dólmenes De Antequera a Través De La Documentación De Simeón Giménez Reyna Existente En El Archivo De La Diputación De Málaga

Los Dólmenes de Antequera a través de la documentación de Simeón Giménez Reyna existente en el Archivo de la Diputación de Málaga. Desde el Archivo de la Diputación de Málaga nos queremos sumar a todas las manifestaciones de apoyo a la candidatura del Sitio de los Dólmenes de Antequera para su inclusión en la lista de bienes considerados Patrimonio Mundial de la Unesco, a la vez que también queremos rendir tributo a la figura de Simeón Giménez Reyna, arqueólogo, quien junto con su amigo Juan Temboury fue el promotor de la conservación monumental de Málaga y uno de los impulsores de la Arqueología malagueña. El Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera está formado por los Dólmenes de Menga, Viera y El Romeral, calificado como uno de los más claros exponentes del megalitismo en Europa, desarrollado desde comienzos del V milenio antes de nuestra era, perteneciente por lo tanto al período Neolítico. Tenemos noticias del Dolmen de Menga, ya en 1530 en una carta del obispo de Málaga, César Riario. Los escritos de los primeros investigadores se centraban básicamente en el Dolmen de Menga, si bien ya desde 1587 hay datos de otro dolmen próximo: el Dolmen de Viera. La publicación de la “Memoria sobre el templo druida hallado en las cercanías de la ciudad de Antequera” escrita en 1847 por el arquitecto Rafael Mitjana y Ardison seria la fuente de la que manarían en el XIX los estudios de diversos autores como Eduardo Chao, Lady Louisa Tenison, Trinidad de Rojas, Manuel de Assas o Joaquín Fernández Ayarragaray. El Dolmen de Menga fue declarado en 1886 Monumento Nacional. -

De Antequera

CREADORES DE MEMORIA: MIRADAS SOBRE LOS DÓLMENES DE ANTEQUERA EXPOSICIÓN MÁLAGA, DEL 20 DE SEPTIEMBRE AL 8 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2013 CREADORES DE MEMORIA: MIRADAS SOBRE LOS DÓLMENES DE ANTEQUERA EXPOSICIÓN MÁLAGA, DEL 20 DE SEPTIEMBRE AL 8 DE NOVIEMBRE DE 2013 EXPOSICIÓN Organiza: Real Academia de Nobles Artes de Antequera y Ámbito Cultural de El Corte Inglés. Colabora: Consejería de Cultura y Deporte de la Junta de Andalucía y Excmo. Ayuntamiento de Antequera. Comisarios: Bartolomé Ruiz González y José Escalante Jiménez. Coordinación y Documentación: Mª del Carmen Andújar Gallego, Miguel Ángel Checa Torres y Victoria Eugenia Pérez Nebreda (Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera). Textos: Margarita Sánchez Romero y Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera. Diseño: Rafael Ángel Gallardo Montiel. CATÁLOGO Dirección y coordinación: Lourdes Jiménez. Textos: Margarita Sánchez Romero y Conjunto Arqueológico Dólmenes de Antequera. Diseño: Francisca Reina, Artigraf Málaga S.L. Créditos fotográficos: Foto Emilio 1931 (Fondo Fotográfico Archivo Durán del Archivo Histórico Municipal de Antequera) y Aurora Villalobos Gómez. © Del texto: los autores. © De las reproducciones: los respectivos autores. © De la presente edición: Ámbito Cultural de El Corte Inglés. Foto portada: Grabado publicado en 1853 por Lady Louisa Tenison en su obra Castile and Andalucia, 1853, p. 275. Foto contraportada: Vista de la Peña desde el interior de Menga. Javier Pérez González, 2007. Edita Centauro. Imprime Artigraf Málaga, S.L. Depósito Legal: MA 1643-2013. NO es fácil encontrar un sitio prehistórico emblemático, de esos a los que llamaríamos “clásicos”, cuya historiografía se remonte casi quinientos años atrás. El caso de la necrópolis megalítica de Antequera, por el contrario, es muy excepcional en este sentido, ya que a juzgar por la información que poseemos hoy, puede decirse que sus dólmenes han sido conocidos ininterrumpidamente desde que se construyeron. -

BLESSED LEOPOLD of ALPANDEIRE 15 August 2010

Circular Letter of the Minister General Mauro Jöhri OFM Cap BLESSED LEOPOLD OF ALPANDEIRE 15 August 2010 www.ofmcap.org © Copyright by: Curia Generale dei Frati Minori Cappuccini Via Piemonte, 70 00187 Roma ITALIA tel. +39 06 420 11 710 fax. +39 06 48 28 267 www.ofmcap.org Ufficio delle Comunicazioni OFMCap [email protected] Roma, A.D. 2016 BLESSED LEOPOLD OF ALPANDEIRE Circular Letter No. 07 BLESSED LEOPOLD OF ALPANDEIRE (1864-1956) Prot. N. 00653/1 In the past few months, the Order has been preparing for a second beatification, once again, in Spain! This time it is the turn of Br. Leopold of Alpandeire, a friar who is close to our own times. His life was not distinguished for any spectacular works but rather for the simplicity and fidelity he put into everything he did. Of him it can be said that he was before all else a “man of God”, steeped in His Spirit. He was a questing friar, and so would go out every day among the people. His was not a position of power: he simply asked, and left the other person free. He would beg alms to support the friars, and leave the giver, in return, with serenity and peace, gifts of the Spirit. Questing in this form, as Br. Leopold exercised it, has all but disappeared in the Order. However, we do need to discover new ways of being present among the people as “lesser brothers”. “Subject to everyone in this world”, says St Francis in the Praises of the Virtues, to give them an opportunity of sharing and to offer them “His peace”, the peace of the Lord Jesus. -

Intervenciones En Los Dólmenes De Antequera (1840-2020)

TRABAJOS DE PREHISTORIA 77, N.º 2, julio-diciembre 2020, pp. 255-272, ISSN: 0082-5638 https://doi.org/10.3989/tp.2020.12255 Intervenciones en los Dólmenes de Antequera (1840-2020). Una revisión crítica* Interventions in the Antequera Dolmens (1840-2020). A critical review Coronada Mora Molinaa y Leonardo García Sanjuána RESUMEN ports, planimetry and photographs) as well as published ma- terial. As a result, we propose a set of criteria that all future Los monumentos megalíticos de Antequera (Málaga) han activities carried out at the site and its surroundings should sido objeto de numerosas excavaciones arqueológicas, tra- meet in order to avoid previous problems, including the dete- bajos de restauración y proyectos de “urbanización” desde rioration of the monuments themselves and losses to the ar- que entre 1842 y 1847 se iniciara la excavación de Menga chaeological record. y en 1903 y 1904 la exploración de Viera y El Romeral. El objetivo principal de estas intervenciones ha sido ampliar el Palabras clave: Patrimonio Mundial; Megalitismo; Menga; conocimiento sobre las construcciones prehistóricas, mejorar Viera; El Romeral; Península ibérica. su estado de conservación y facilitar su acceso al público. Sin embargo, muchas de ellas han tenido consecuencias ne- Key words: World Heritage; Megalithism; Menga; Viera; gativas para la conservación y el conocimiento científico de El Romeral; Iberian peninsula. los monumentos. Este artículo valora críticamente estas in- tervenciones a partir del análisis de la documentación dis- ponible, consistente en proyectos previos, informes y me- morias, planimetría, fotografías y publicaciones. Además, 1. INTRODUCCIÓN planteamos un conjunto de criterios que todas las actividades futuras realizadas en los megalitos antequeranos y sus alre- dedores deberían cumplir para evitar el deterioro y la pérdi- Los dólmenes de Antequera están enclavados en el da de registro arqueológico.