Toccata Classics TOCC0199 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ernst Kovacic Biography Biography Violin / Conductor Conductor

Ikon Arts Management Ltd Suite 114, Business Design Centre 52 Upper Street , London N1 0QH t: +44 (0)20 7354 9199 f: +44 (0)870 130 9646 [email protected] m Ernst Kovacic Biography www.ikonarts.com Violin / Conductor “‘One of the most creative and accomplished violinists worldwide” The Sunday Times Website www. ernstkovacic.com Contact Pippa Patterson Email pippa @ikonarts.com Vienna, with its fruitful tension between tradition and innovation, inspires the Austrian violinist and conductor Ernst Kovacic. A regular visitor to Britain, Ernst Kovacic has worked with all of the major UK orchestras, most recently appearing with the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra performing Gyorgy Ligeti’s Violin Concerto and later performing Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto with the Ulster Orchestra. Ernst Kovacic is a leading performer throughout Europe and the USA. His recent guest engagements include appearances with the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna Symphony, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Czech Philharmonic, Prague Symph ony, Detroit Symphony, Budapest Symphony, Netherlands Radio Philharmonic, Tivoli Symphony and the Radio Symphony Orchestras of Berlin, Bayerischer Rundfunk, Sudwestfunk, Hessischer Rundfunk, Norddeutscher Rundfunk and the Konzerthausorchester Berlin among many others. Ernst makes frequent international festival appearances. He gave a critically /acclaimed performance of the Schoenberg Violin Concerto at the BBC Proms and has appeared at the Edinburgh Festival, the major festivals of Berlin, Vienna and Salzburg, as well as the Ultima Oslo and Prague Autumn Festivals. Increasingly busy as a conductor, Ernst has been the artistic director of the Le opoldinum Chamber Orchesta in Wroclaw, Poland since 2007. He has directed the Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ulster Orchestra, Northern Sinfonia, Camerata Salzburg, Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie, Klangforum, Ensemble Modern, Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra, Camera ta Bern, Camerata Nordica, Zagreb Philharmonic and the Taipei Symphony Orchestra. -

CONDUCTOR Sergio Alapont Winner As Best Conductor in Italy 2016 Of

CONDUCTOR Sergio Alapont Winner as Best Conductor in Italy 2016 of the Opera Awards GBOPERA, and winner of the II Competition for Conductors City of Granada Orchestra, Sergio Alapont is one of the leading conductors of his generation, Resident Conductor of Suzhou Symphony Orchestra in China, Music Director of Orizzonti Festival in Italy, Principal Conductor of Orquesta Manuel de Falla and Artistic Director of Opera Benicàssim. Future engagements for Mr. Alapont include Orchestra Giuseppe Verdi di Milano, Orchestra del Maggio Musicale Fiorentino, Orchestra di Padova e del Veneto, Orchestra della Toscana, Suzhou Symphony Orchestra (China), Opening Season Gala Concert with Haifa Symphony Orchestra (Israel), Norma at the Teatro Comunale di Ferrara, La Medium and Madama Butterfly at the Orizzonti Festival 2017, Lucia di Lammermoor at the Teatro Comunale di Treviso and Teatro Comunale di Ferrara, La forza del destino at the Las Palmas Opera, Madama Butterfly at the Palau de Les Arts of Valencia, Gala Concert at the Gran Teatre del Liceu de Barcelona or Gala Concert with the Orquesta Sinfónica de Madrid at the Teatro Real de Madrid Conrad van Alphen Conrad van Alphen is known as much for entrepreneurial spirit and depth of preparation as he his is for performances that combine exceptional sensitivity, vision and freshness. He enjoys a particularly close association with the Russian National Orchestra and is currently an artist of the Moscow Philharmonic Society. As a guest conductor Conrad works with some of the world’s most respected orchestras, such as the Montreal and Svetlanov Symphony Orchestras, the Brussels, Bogota and Moscow Philharmonics, the Bochumer Symphoniker as well as the Symphony Orchestra of the Gran Teatre del Liceu in Barcelona. -

18 July, 2021 the International Summer Academy Offers

INTERNATIONAL SUMMER ACADEMY IN LILIENFELD, AUSTRIA The International Summer Academy offers courses and lectures held by 4 – 18 July, 2021 internationally renowned artists and teachers. The participants can present their works, as prepared during the courses, to a public audience. This years’ Summer Academy will take place for the 40th time. The opening will be celebrated on July 4th, 2021. In celebration of the 40th Summer Academy, the opening event with the performance of Ludwig van Beethoven’s opera Fidelio will be particularly festive. The members of Amadeus Brass Quintet will also be celebrating their 15th year of teaching at the SAL with a brilliant 20 musicians brass orchestra concert in the 2nd week. As a place of inspiration, the SAL once again offers vocal and instrumental courses taught by recognized experts and pedagogues. Students and teachers perform together in Holy masses, in lecturer and participants concerts. These performances and the academic depth achieved by the exchange of ideas have a high educational value. They encourage artistic and human connections between many countries of the world. The director Karen De Pastel, the lecturers and the organizational team is looking forward to welcoming you in Lilienfeld! 1 The participation in the master courses is open to all students, musicians and music lovers. There is no age limitation for active participation. Forming REGISTRATION FEE instrumental and vocal ensembles is encouraged. Violinists who play viola as The registration fee is part of the course fee: a second instrument are free to choose one of the two instruments for o ACTIVE PARTICIPANTS EUR 60,- performance in ensemble groups. -

Decca Discography

DECCA DISCOGRAPHY >>V VIENNA, Austria, Germany, Hungary, etc. The Vienna Philharmonic was the jewel in Decca’s crown, particularly from 1956 when the engineers adopted the Sofiensaal as their favoured studio. The contract with the orchestra was secured partly by cultivating various chamber ensembles drawn from its membership. Vienna was favoured for symphonic cycles, particularly in the mid-1960s, and for German opera and operetta, including Strausses of all varieties and Solti’s “Ring” (1958-65), as well as Mackerras’s Janá ček (1976-82). Karajan recorded intermittently for Decca with the VPO from 1959-78. But apart from the New Year concerts, resumed in 2008, recording with the VPO ceased in 1998. Outside the capital there were various sessions in Salzburg from 1984-99. Germany was largely left to Decca’s partner Telefunken, though it was so overshadowed by Deutsche Grammophon and EMI Electrola that few of its products were marketed in the UK, with even those soon relegated to a cheap label. It later signed Harnoncourt and eventually became part of the competition, joining Warner Classics in 1990. Decca did venture to Bayreuth in 1951, ’53 and ’55 but wrecking tactics by Walter Legge blocked the release of several recordings for half a century. The Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra’s sessions moved from Geneva to its home town in 1963 and continued there until 1985. The exiled Philharmonia Hungarica recorded in West Germany from 1969-75. There were a few engagements with the Bavarian Radio in Munich from 1977- 82, but the first substantial contract with a German symphony orchestra did not come until 1982. -

Mozart Evening in Vienna

--BBBBB NAXOS 11111 A Mozart Evening in Vienna Vienna Mozart Orchestra Konrad Leitner Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756 - 1791) Aus der Oper "Die Entfuhrung aus dem Serail", KV 384 From the opera The Abduction from the Seraglio, K. 384 OuvertureIOverture Arie des Blondchens/Blondchen's Aria "Durch Zartlichkeit . " Aus der Oper "Don Giovanni", KV 527 From the opera Don Giovanni, K. 527 Canzonetta des Don GiovannilDon Giovanni's Canzonetta "Deh, vieni alla finestra" Duett Don Giovanni-Zerlina:/Duet of Don Giovanni and Zerlina "La ci darem la mano" Eine kleine Nachtmusik, KV 525 Serenade in G, K. 525 1. Allegro Konzert fur Klavier Nr. 21, C-Dur, KV 467 Piano Concerto No. 21 in C major, K. 467 2. Andante 3. Allegro vivace assai Symphonie Nr. 41, "Jupiter", KV 551 Sym hony No. 41, Jupiter, K. 551 1. AIL~~Ovivace Konzert fur Violine, A-Dur, KV 219 Violin Concerto in A major, K. 219 3. Rondo: Tempo di Menuetto Aus der Oper "Don Giovanni", KV 527 From the opera Don Giovanni, K. 527 Arie des Leporello - Registerarie/LeporelloFsCatalogue Song: "Madamina ! " Aus der Oper "Don Giovanni", KV 527 From the opera Don Giovanni, K. 527 Arie der ZerlinaIZerlina's Aria "Vedrai, carino" Aus der Oper "Die Zauberflote", KV 620 From the opera The Magic Flute, K. 620 Arie des PapagenoIPapageno's Aria "Ein Madchen oder Weibchen" Alla turca (Orchesterbearbeitung) Rondo alla turca (orchestral arrangement) Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart was born in Salzburg in 1756, the son of a court musician who, in the year of his youngest child's birth, published an influential book on violin-playing. -

Media Kit 2015 Season

MEDIA KIT 2015 SEASON Partnerships www.australianworldorchestra.com.au MEDIA RELEASE The Australian World Orchestra brings Australia’s finest musical talent home for three extraordinary concerts “… the Mehta Stravinsky and Mahler concert was such a thrilling night of brilliant musicianship (always GREAT when Melbourne audiences get to their feet in rapture!)” – Geoffrey Rush “The Australian World Orchestra brings together some of the finest musicians I have had the pleasure to make music with. I adored conducting them last year.” – Zubin Mehta In July/August 2015, the Australian World Orchestra (AWO) performs under the baton of Chief Conductor of the Berlin Philhar- monic Orchestra, Sir Simon Rattle, together with internationally renowned mezzo-sopranoMagdalena Kožená. AWO will perform three electrifying performances in Australia, at the Sydney Opera House and the Arts Centre Melbourne, Hamer Hall, before the orchestra makes its international debut, accepting Zubin Mehta’s invitation to perform in India in October 2015. AWO Founder and Artistic Director, Alexander Briger, said: “It’s so exciting that the AWO will come together in 2015 to work with the incomparable Sir Simon Rattle in Australia, and that we give our first international performances, reuniting with Maestro Zubin Mehta in India.” Since its inaugural concert series in 2011, AWO has dazzled Australian audiences and established its place as one of the world’s premier orchestras. Founded through the creative vision of internationally acclaimed conductor Alexander Briger, AWO brings Australia’s utmost classical music talent from around the world to perform together. The 2015 season includes 95 Australian musicians from over 30 cities and 45 of the world’s leading orchestras and ensembles, from the Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras, the Royal Concertgebouw, and the London and Chicago Symphony Orchestras, as well as Australia’s own magnificent state orchestras. -

Journal of the American Viola Society Volume 8 No. 1, 1992

WILLIAM PRIMROSE, 1904 - 1982 Commerrwrative issue on the 10th Anniversary of his Death JOURNAL oftlze AMERICANVIOLA SOCIETY Chapter of THE INTERNATIONAL VIOLA SOCIETY Association for the Promotion of Viola Performance and Research Vol. 8 No.1 1992 The Journal of the American Viola Society is a publication of that organization, and is produced at Brigham Young UniversitY,@1985, ISSN 0898-5987. The Journal welcomes letters and artioles from its readers. Editorial and Advertising OJ/ice: BYU Music, Harris Fine Arts Center, Provo, UT 84602, (801) 378-3083 Editor. David Dalton Assistant Editor: David Day JAVS appears three times yearly. Deadlines for copy and art work are March I, June I, and October I and should be sent to the editorial office. Rates: $75 full page, S60 two-thirds page, S40 half page, 533 one-third page, S25 one-fourth page. For classifieds: $10 for 30 words including address; $20 for 31 to 60 words. Advertisers will be billed after the ad has appeared. Payment to •American Viola Society· should be remitted to the editorial office. OFFICERS Alan de Veriteh President School of .vlusic Unil'erslhJ of So Californza 830 West )4th Street RilmoHalll12 Los Angeles. CA 90089 (8051255-0693 Harold CoLetta Vice-PreSldmt 5 Old Mill Road = West Nyack, ,"'Y 10994 Pamew Goldsmith Secreta11l 1I640 Amanda Dm'e StudIO City, CA 91604 R(lsemarv Chide Treasure;, ~ P.O. Box 558 Golden', Bridge, NY 10526 D1l'la Dalton Past PreSldOlt Editor, /AVS Brigham Young UlIHyrslty Provo, UT 84602 --~I ---I BOARD -~I Louis Kiel'man Wilham Magers Donald McInnes l<£lthryn Plummer DullgJa Pounds ~'l/Illiam PreuCiI Thomas Tatton lv11chael Tree Karen Tuttle Emarwel Vardi Robert Vernon Antl Woodward PAST PRESIDENTS Maurice Rllev f1981-86) Myron Rosenblum (]971-81J HONORARY PRESIDENT William PnmroSt' (deceased) ~Cf?r;fChapter of the IntenzatiOlzale Vioia-Gesellschaft Announcement The premier publication by the American Viola Society, under the direction of the AVS Publications Department, for the benefit of its members and their society. -

MBTS 2019 Programme

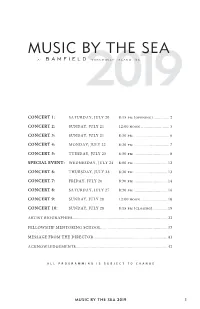

MUSIC BY THE SEA AT BAMFIELD2 VANCOUVER0 ISLAND,1 BC 9 CONCERT 1: SATURDAY, JULY 20 8:15 pm (opening) .............. 2 CONCERT 2: SUNDAY, JULY 21 12:00 noon ......................... 5 CONCERT 3: SUNDAY, JULY 21 8:30 pm ............................... 6 CONCERT 4: MONDAY, JULY 22 8:30 pm ............................... 7 CONCERT 5: TUESDAY, JULY 23 8:30 pm ............................... 8 SPECIAL EVENT: WEDNESDAY, JULY 24 8:00 pm ............................. 12 CONCERT 6: THURSDAY, JULY 25 8:30 pm ............................. 13 CONCERT 7: FRIDAY, JULY 26 8:30 pm ............................. 14 CONCERT 8: SATURDAY, JULY 27 8:30 pm ............................. 16 CONCERT 9: SUNDAY, JULY 28 12:00 noon ........................ 18 CONCERT 10: SUNDAY, JULY 28 8:15 pm (closing) ............. 19 ARTIST BIOGRAPHIES .................................................................................... 22 FELLOWSHIP MENTORING SCHOOL ........................................................... 35 MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR ................................................................. 41 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ................................................................................. 42 ALL PROGRAMMING IS SUBJECT TO CHANGE MUSIC BY THE SEA 2019 1 CONCERT 1 CONCERT 1 continued Saturday, July 20th ~ 8:15 PM Three Fanfares, for horn in a distant rowboat C. Donison Suite from “On the Overgrown Path” Leoš Janáček and tuned ships horns (2015) (b. 1952) (1854–1928) 8:15 pm I. Call and response between distant rowboat and boats Our evenings (with cannon -

2017–18 Season Week 24 Brahms Prokofiev

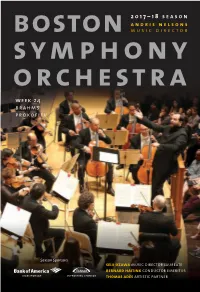

2017–18 season andris nelsons music director week 24 brahms prokofiev Season Sponsors seiji ozawa music director laureate bernard haitink conductor emeritus supporting sponsorlead sponsor supporting sponsorlead thomas adès artistic partner Better Health, Brighter Future There is more that we can do to help improve people’s lives. Driven by passion to realize this goal, Takeda has been providing society with innovative medicines since our foundation in 1781. Today, we tackle diverse healthcare issues around the world, from prevention to care and cure, but our ambition remains the same: to find new solutions that make a positive difference, and deliver better medicines that help as many people as we can, as soon as we can. With our breadth of expertise and our collective wisdom and experience, Takeda will always be committed to improving the Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited future of healthcare. www.takeda.com Takeda is proud to support the Boston Symphony Orchestra Table of Contents | Week 24 7 bso news 1 5 on display in symphony hall 17 in memoriam: john oliver 2 0 bso music director andris nelsons 2 2 the boston symphony orchestra 2 6 this week’s program Notes on the Program 28 The Program in Brief… 29 Johannes Brahms 39 Sergei Prokofiev 49 To Read and Hear More… Guest Artists 53 Tugan Sokhiev 55 Vadim Gluzman 60 sponsors and donors 78 future programs 82 symphony hall exit plan 8 3 symphony hall information the friday preview on april 27 is given by bso director of program publications marc mandel. program copyright ©2018 Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

01 02 2018 CRQ EDITIONS COMPLETE CATALOGUE V23a No

CRQ EDITIONS – CATALOGUE @ 01.02.2018 Verdi: Ernani (abridged) Iva Pacetti / Antonio Melandri / Gino Vanelli / Corrado Zambelli / Ida Mannarini / Aristide Baracchi / Giuseppe Nessi / Chorus and Orchestra of La Scala, Milan / Lorenzo Molajoli Classic Record Quarterly Editions CRQ CD001 (1 CD) Tchaikovsky: Symphony No. 6 in B minor, ‘Pathétique’, Op. 74 London Philharmonic Orchestra / Sir Adrian Boult Classic Record Quarterly Editions CRQ CD002 (1 CD) Homage to Mogens Wöldike Danish State Radio Chamber Orchestra / Mogens Wöldike J. C. Bach: Sinfonia in B flat major Op. 18 No. 2; F. J. Haydn: Divertimento in G major; F. J. Haydn: Six German Dances; W. A. Mozart: Symphony No. 14 in A major, K. 114; K. D. von Dittersdorf: Symphony in C major Classic Record Quarterly Editions CRQ CD003 (1 CD) Verdi: Macbeth Margherita Grandi, Walter Midgley, Francesco Valentino, Italo Tajo Glyndebourne Festival Chorus, Scottish Orchestra / Berthold Goldschmidt, conductor Recording of the performance of 27th August 1947 given by Glyndebourne Festival Opera at the first Edinburgh Festival, Classical Recordings Quarterly Editions CRQ CD004/005 (2 CDs) Busoni: Fantasia Contrapuntistica; Bach-Busoni: Chorale Prelude: Ich ruf’ zu dir, Herr Jesu Christ Alfred Brendel, piano Classical Recordings Quarterly Editions CRQ CD006 (1 CD) Rudolf Schwarz conducts Philharmonia Orchestra / Rudolf Schwarz Weber: Euryanthe Overture; Schubert: Symphony No. 8, Unfinished; Liszt: Les préludes Classical Recordings Quarterly Editions CRQ CD007 (1 CD) Berg: Wozzeck (complete); Violin Concerto Wozzeck: Marea Wolkowsky, Monica Sinclair, Edgar Evans, Thorsteinn Hannesson, Parry Jones, Jess Walters, Frederick Dalberg; Chorus and Orchestra of the Covent Opera Company / Erich Kleiber Broadcast performance of 25 May 1953 given at the Royal Opera House, London. -

Wolfgang Panhofer Cello

Wolfgang Panhofer cello Born in Vienna, Wolfgang Panhofer studied at the Vienna Academy and at the Royal Northern College of Music with Ralph Kirshbaum. He has had masterclasses with Paul Tortelier, William Pleeth, Boris Pergamen- schikow, and Steven Isserlis, and studied chamber Music with Andras Schiff and Peter Schidloff of the Ama- deus Quartet. At the age of 17 he was one of the youngest members to play with the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. He has performed concerts throughout Europe, Asia, the Middle East, Africa and the USA where he gave his debut at the Carnegie Hall in 2000. Numerous Radio and Television Broadcast performances include Eurovi- sion under Franz Welser-Moest, a live broadcast shown in 8 countries within Europe; with Paul Tortelier for the BBC; with the Katowice Philharmonic Orchestra for Polish Television; and a special report on Slovenian TV. He has performed concerts under Lord Yehudi Menuhin, Franz Welser Moest, Martin Sieghart, Cornelius Meister, Jerzy Maksymiuk, Hans Zender and many others. For the 150th Birthday Anniversary Concert of Antonin Dvorak at the Vienna Concerthaus he was invited to play with Josef Suk, Dvorak´s greatgrandson. Wolfgang has given concerts with world renowned orchestras (Vienna Symphony, Niederösterreichische Tonkünstler Orchestra, Vienna Chamber Orchestra, the chamber music ensemble of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, the Philharmonics of Graz, Lodz, Poznan, Katowice, Kosice, the Baltic Philharmonic, the Slovenian Soloists Orchestra, the Adriatic Philharmonic Ancona, Arthur Rubinstein Philharmonic, Opera Orchestra Ljubljana etc.) and is a sought guest of international festivals. He just recorded all Beethoven Sonatas for the american label MMO. In 2009 Wolfgang Panhofer recorded a concerto for violoncello by Marko Mihevc with the Slovenian Soloist Orchestra. -

The Competition Jury 2012

© Jeff Klein © Caroline Doutre © Robert Romik © Paul Mitchell © Malcolm Crowthers Pamela Frank Joji Hattori Olivier Charlier Dong-Suk Kang Hu Kun Henning Tasmin Little Yan Pascal Vera Tsu Kraggerud Tortelier Wei Ling The Competition Jury 2012 PAMELA FRANK (USA) Chair of the Jury invited to perform with national and international orchestras artist. He won first prize in the 1985 Menuhin Competition, charity that uses music to transform the lives of disadvan- Pamela Frank has established an outstanding international including the Orchestre National de France, Zurich’s Tonhalle and was invited by Yehudi Menuhin himself to London to taged young people. reputation across an unusually varied range of performing Orchestra, The Hague Philharmonic Orchestra, the London become his only private student. Recently, Kun has taken up activity. As a soloist she has performed with leading Philharmonic Orchestra, the BBC Philharmonic, the Hallé conducting, tutored by Sir Colin Davis. Kun is a professor at YAN PASCAL TORTELIER (France) orchestras including the New York Philharmonic, the Chicago Orchestra and the Berlin Symphony Orchestra, and under such the Royal Academy of Music in London and a guest professor Yan Pascal Tortelier has conducted some of the world’s most Symphony Orchestra, the San Francisco Symphony, the revered conductors as Gianandrea Noseda, Gustavo Dudamel at the Central Conservatory of Music, the Sichuan Chengdu prestigious orchestras including the London Symphony Academy of St Martin-in-the-Fields, the Berlin Philharmonic, and Yan Pascal Tortelier, the latter of whom joins Charlier on Conservatory and at the Xinghai Conservatory in Guangzhou. Orchestra, the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the St the Vienna Symphony Orchestra, the Orchestre National de this year’s jury.