OECD Economic Surveys POLAND March 2014 OVERVIEW

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seventy-Ninth Annual Pulaski Day Parade Sunday, October 2, 2016 Fifth Avenue, New York City

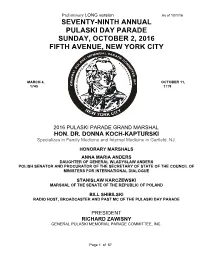

Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 SEVENTY-NINTH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016 FIFTH AVENUE, NEW YORK CITY MARCH 4, OCTOBER 11, 1745 1779 2016 PULASKI PARADE GRAND MARSHAL HON. DR. DONNA KOCH-KAPTURSKI Specializes in Family Medicine and Internal Medicine in Garfield, NJ. HONORARY MARSHALS ANNA MARIA ANDERS DAUGHTER OF GENERAL WLADYSLAW ANDERS POLISH SENATOR AND PROCURATOR OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE OF THE COUNCIL OF MINISTERS FOR INTERNATIONAL DIALOGUE STANISLAW KARCZEWSKI MARSHAL OF THE SENATE OF THE REPUBLIC OF POLAND BILL SHIBILSKI RADIO HOST, BROADCASTER AND PAST MC OF THE PULASKI DAY PARADE PRESIDENT RICHARD ZAWISNY GENERAL PULASKI MEMORIAL PARADE COMMITTEE, INC. Page 1 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 ASSEMBLY STREETS 39A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. M A 38 FLOATS 21-30 38C FLOATS 11-20 38B 38A FLOATS 1 - 10 D I S O N 37 37C 37B 37A A V E 36 36C 36B 36A 6TH 5TH AVE. AVE. Page 2 of 57 Preliminary LONG version As of 10/1/16 PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE THE 79TH ANNUAL PULASKI DAY PARADE COMMEMORATING THE SACRIFICE OF OUR HERO, GENERAL CASIMIR PULASKI, FATHER OF THE AMERICAN CAVALRY, IN THE WAR OF AMERICAN INDEPENDENCE BEGINS ON FIFTH AVENUE AT 12:30 PM ON SUNDAY, OCTOBER 2, 2016. THIS YEAR WE ARE CELEBRATING “POLISH- AMERICAN YOUTH, IN HONOR OF WORLD YOUTH DAY, KRAKOW, POLAND” IN 2016. THE ‘GREATEST MANIFESTATION OF POLISH PRIDE IN AMERICA’ THE PULASKI PARADE, WILL BE LED BY THE HONORABLE DR. DONNA KOCH- KAPTURSKI, A PROMINENT PHYSICIAN FROM THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY. -

SPACE RESEARCH in POLAND Report to COMMITTEE

SPACE RESEARCH IN POLAND Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) 2020 Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Report to COMMITTEE ON SPACE RESEARCH (COSPAR) ISBN 978-83-89439-04-8 First edition © Copyright by Space Research Centre Polish Academy of Sciences and The Committee on Space and Satellite Research PAS Warsaw, 2020 Editor: Iwona Stanisławska, Aneta Popowska Report to COSPAR 2020 1 SATELLITE GEODESY Space Research in Poland 3 1. SATELLITE GEODESY Compiled by Mariusz Figurski, Grzegorz Nykiel, Paweł Wielgosz, and Anna Krypiak-Gregorczyk Introduction This part of the Polish National Report concerns research on Satellite Geodesy performed in Poland from 2018 to 2020. The activity of the Polish institutions in the field of satellite geodesy and navigation are focused on the several main fields: • global and regional GPS and SLR measurements in the frame of International GNSS Service (IGS), International Laser Ranging Service (ILRS), International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS), European Reference Frame Permanent Network (EPN), • Polish geodetic permanent network – ASG-EUPOS, • modeling of ionosphere and troposphere, • practical utilization of satellite methods in local geodetic applications, • geodynamic study, • metrological control of Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) equipment, • use of gravimetric satellite missions, • application of GNSS in overland, maritime and air navigation, • multi-GNSS application in geodetic studies. Report -

Integration Policy and Activities in Poland

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Cadmus, EUI Research Repository INTERACT – RESearcHING THIRD COUNTRY NatiONALS’ INTEGratiON AS A THREE-WAY PROCESS - IMMIGrantS, COUNTRIES OF EMIGratiON AND COUNTRIES OF IMMIGratiON AS ActORS OF INTEGratiON Integration Policy and Activities in Poland Renata Stefańska INTERACT Research Report 2015/07 CEDEM INTERACT Researching Third Country Nationals’ Integration as a Three-way Process - Immigrants, Countries of Emigration and Countries of Immigration as Actors of Integration Research Report Country Report INTERACT RR2015/07 Integration Policy and Activities in Poland Renata Stefańska Research Associate at the Centre of Migration Research, University of Warsaw This text may be downloaded only for personal research purposes. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copies or electronically, requires the consent of the Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies. Requests should be addressed to [email protected] If cited or quoted, reference should be made as follows: Renata Stefańska, Integration Policy and Activities in Poland, INTERACT RR 2015/07, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies, San Domenico di Fiesole (FI): European University Institute, 2015. The opinions expressed are those of the author(s) only and should not be considered as representative of the official position of the European Commission or of the European University Institute. © 2015, European University Institute ISBN: 978-92-9084-272-9 DOI: 10.2870/938460 Catalogue Number: QM-02-15-127-EN-N European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy http://www.eui.eu/RSCAS/Publications/ http://interact-project.eu/publications/ http://cadmus.eui.eu INTERACT - Researching Third Country Nationals’ Integration as a Three-way Process - Immigrants, Countries of Emigration and Countries of Immigration as Actors of Integration In 2013 (Jan. -

Pride and Prejudice : Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden

Pride and Prejudice Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden Anna Malmquist Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 642 Linköping Studies in Behavioural Science No. 191 Linköping University Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning Linköping 2015 Linköping Studies in Arts and Science No. 642 Linköping Studies in Behavioural Science No. 191 At the Faculty of Arts and Science at Linköping University, research and doctoral studies are carried out within broad problem areas. Research is organized in interdisciplinary research environments and doctoral studies mainly in graduate schools. Jointly, they publish the series Linköping Studies in Arts and Science. This thesis comes from the Division of Psychology at the Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning. Distributed by: Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning Linköping University SE - 581 83 Linköping Anna Malmquist Pride and Prejudice: Lesbian Families in Contemporary Sweden Cover painting: Kristin Winander Upplaga 1:1 ISBN 978-91-7519-087-7 ISSN 0282-9800 ISSN 1654-2029 ©Anna Malmquist Department of Behavioural Sciences and Learning, 2015 Printed by: LiU-tryck, Linköping 2015 To my children, Emil, Nils, Myran and Tove Färgen på barns ögon kommer från arvet, glittret i barns ögon kommer från miljön. The colour of children’s eyes comes from nature, the sparkle in children’s eyes comes from nurture. Abstract Options and possibilities for lesbian parents have changed fundamentally since the turn of the millennium. A legal change in 2003 enabled a same-sex couple to share legal parenthood of the same child. An additional legal change, in 2005, gave lesbian couples access to fertility treatment within public healthcare in Sweden. -

Re-Branding a Nation Online: Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism

Re-Branding a Nation Online Re-Branding a Nation Online Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism Magdalena Kania-Lundholm Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Sal IX, Universitets- huset, Uppsala, Friday, October 26, 2012 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Kania-Lundholm, M. 2012. Re-Branding A Nation Online: Discourses on Polish Nationalism and Patriotism. Sociologiska institutionen. 258 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-506-2302-4. The aim of this dissertation is two-fold. First, the discussion seeks to understand the concepts of nationalism and patriotism and how they relate to one another. In respect to the more criti- cal literature concerning nationalism, it asks whether these two concepts are as different as is sometimes assumed. Furthermore, by problematizing nation-branding as an “updated” form of nationalism, it seeks to understand whether we are facing the possible emergence of a new type of nationalism. Second, the study endeavors to discursively analyze the ”bottom-up” processes of national reproduction and re-definition in an online, post-socialist context through an empirical examination of the online debate and polemic about the new Polish patriotism. The dissertation argues that approaching nationalism as a broad phenomenon and ideology which operates discursively is helpful for understanding patriotism as an element of the na- tionalist rhetoric that can be employed to study national unity, sameness, and difference. Emphasizing patriotism within the Central European context as neither an alternative to nor as a type of nationalism may make it possible to explain the popularity and continuous endur- ance of nationalism and of practices of national identification in different and changing con- texts. -

Andrea Principi Per H. Jensen Giovanni Lamura ACTIVE AGEING Voluntary Work by Older People in Europe

ACTIVE AGEING VOLUNTARY WORK BY OLDER PEOPLE IN EUROPE EDITED BY Andrea Principi Per H. Jensen Giovanni Lamura ACTIVE AGEING Voluntary work by older people in Europe Edited by Andrea Principi, Per H. Jensen and Giovanni Lamura First published in Great Britain in 2014 by Policy Press North America office: University of Bristol Policy Press 6th Floor c/o The University of Chicago Press Howard House 1427 East 60th Street Queen’s Avenue Chicago, IL 60637, USA Clifton t: +1 773 702 7700 Bristol BS8 1SD f: +1 773-702-9756 UK [email protected] t: +44 (0)117 331 5020 www.press.uchicago.edu f: +44 (0)117 331 5369 [email protected] www.policypress.co.uk © Policy Press 2014 The digital PDF version of this title [978-1-4473-5476-5] is available Open Access and distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) which permits adaptation, alteration, reproduction and distribution for non- commercial use, without further permission provided the original work is attributed. The derivative works do not need to be licensed on the same terms. An electronic version of this book [978-1-4473-5476-5] is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found Knowledge Unlatched at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A catalog record for this book has been requested ISBN 978 1 44730 720 4 hardcover The right of Andrea Principi, Per H. -

EU Energy Markets in 2014

ISSN 1831-5666 EU Energy Markets in 2014 Energy EU Energy Markets in 2014 This publication presents an adapted version of the Commission Staff Working Documents SWD (2014) 310 final and SWD (2014) 311 final accompanying the Communication «Progress towards completing the Internal Energy Market» COM (2014) 634 final of 13 October 2014. Legal notice: The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this publication, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. Some data included in this report are subject to database rights and/or third party copyright. Europe Direct is a service to help you find answers to your questions about the European Union Freephone number (*): 00 800 6 7 8 9 10 11 (*) The information given is free, as are most calls (though some operators, phone boxes or hotels may charge you). More information on the European Union is available on the Internet (http://europa.eu). Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2014 ISBN 978-92-79-37962-8 doi:10.2833/2400 © European Union, 2014 Reproduction is authorised provided the source is acknowledged. Printed in Belgium Printed on white chlorine-free paper Table of contents 1. Trends and Developments in European Energy Markets 2014 .............. 6 1. Energy position of the EU ................................................................ 6 1.1. EU energy consumption ............................................................... 6 1.1.1. Gross Inland Consumption ...................................................... 6 1.1.2. Uses of energy sources by sector ................................................ 6 1.1.3. Energy intensity ................................................................ 8 1.2. EU energy supply ..................................................................... 9 1.2.1. EU primary energy production ................................................... 9 1.2.2. -

Beauty Queens Crowned by Modern Jewish Print Media

German Studies Faculty Publications German Studies 2013 Recognition for the ‘Beautiful Jewess’: Beauty Queens Crowned by Modern Jewish Print Media Kerry Wallach Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gerfac Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, German Language and Literature Commons, and the History of Religions of Western Origin Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Recommended Citation Wallach, Kerry. “Recognition for the ‘Beautiful Jewess’: Beauty Queens Crowned by Modern Jewish Print Media.” In Globalizing Beauty: Consumerism and Body Aesthetics in the Twentieth Century, edited by Hartmut Berghoff and Thomas Kühne. New York: Palgrave Macmillan (2013): 131-150. This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/gerfac/21 This open access book chapter is brought to you by The Cupola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The Cupola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Recognition for the ‘Beautiful Jewess’: Beauty Queens Crowned by Modern Jewish Print Media Abstract This chapter demonstrates how women’s bodies were appropriated (in times of adversity) to promote Jewishness and Jewish ethnic/racial body aesthetics in a variety of locations, including Europe (Germany, Poland, Hungary), -

Social Dialogue in Face of Changes on the Labour Market in Poland

Professor Jacek P. Męcina (prof. UW dr hab.), is a lawyer and a political scientist, as well as a social policy expert on labour law, employment relations, employment policy, and social dialogue. His research interests JACEK M are focused on employment and labour market policy, labour law, and collective labour relations, the conditions of functioning of social dialogue JACEKJACEK MMĘĘCINACINA in Poland and in the European countries. Professor at the Institute of Social Policy, the Faculty of Political Science and International Studies at the University of Warsaw, since 2016 Director of the Institute of Social Policy. Scholar of the European Programme TEMPUS and the Alexander von Hum- Social Dialogue boldt Foundation. A member of the Scientifi c Council of the academic journals — Human Resource Management and Social Dialogue and Social Ę in Face of Changes Policy. The Author of more than 100 books, articles, and papers on labour law, labour relations, social CINA in Face of Changes dialogue, employment and labour market issues. He cooperates with the European institutions, the ILO, and many academic and research centres in Poland, Germany and other European countries. on the Labour Market Poland has been building its market economy for slightly more than a quarter of a century and has been a member of the European Union for thirteen years. Currently, Poland can feel the results of the in Poland. international crisis, but with some delay compared to the other European countries. Despite its stable Crisis to Breakthrough From of Changes on the Labour Social Dialogue in Face Market in Poland. economic development and relatively low unemployment, a deterioration in the quality of labour From Crisis relations is noticeable, and what is more Poland recorded a rapid increase in such forms of atypical employment and fi xed-term employment, reaching the highest levels among the EU countries. -

Download.Xsp/WMP20100280319/O/M20100319.Pdf (Last Accessed 15 April 2018)

Milieux de mémoire in Late Modernity GESCHICHTE - ERINNERUNG – POLITIK STUDIES IN HISTORY, MEMORY AND POLITICS Herausgegeben von / Edited by Anna Wolff-Pow ska & Piotr Forecki ę Bd./Vol. 24 GESCHICHTE - ERINNERUNG – POLITIK Zuzanna Bogumił / Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper STUDIES IN HISTORY, MEMORY AND POLITICS Herausgegeben von / Edited by Anna Wolff-Pow ska & Piotr Forecki ę Bd./Vol. 24 Milieux de mémoire in Late Modernity Local Communities, Religion and Historical Politics Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data A CIP catalog record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Cover image: © Dariusz Bogumił This project was supported by the National Science Centre in Poland grant no. DEC-2013/09/D/HS6/02630. English translation and editing by Philip Palmer Reviewed by Marta Kurkowska-Budzan, Jagiellonian University ISSN 2191-3528 ISBN 978-3-631-67300-3 (Print) E-ISBN 978-3-653-06509-1 (E-PDF) E-ISBN 978-3-631-70830-9 (EPUB) E-ISBN 978-3-631-70831-6 (MOBI) DOI 10.3726/b15596 Open Access: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 unported license. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ © Zuzanna Bogumił / Małgorzata Głowacka-Grajper, 2019 Peter Lang –Berlin ∙ Bern ∙ Bruxelles ∙ New York ∙ Oxford ∙ Warszawa ∙ Wien This publication has been peer reviewed. www.peterlang.com Bibliographic Information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Acknowledgments Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de. -

Adam Nergal Darski

MAGAZYN MAZOWIECKIEGO PORTU LOTNICZEGO WARSZAWA-MODLIN / MASOVIA WARSZAWA-MODLIN AIRPORT MAGAZINE ADAM NERGAL DARSKI TAKE YOUR FREE COPY airport-free-wifi 01 / 2015 (16) TOWARZYSZ PODRÓŻY ZDJĘCIE NA OKŁADCE: FELLOW TRAVELLER Monika Szałek 10 Adam Nergal Darski: Z jaj Adam Nergal Darski: Right from the balls WYDAWCA / PUBLISHER asz-reklama.eu ul. Kościuszki 61, 81-703 Sopot WŁAŚCIWY KURS RIGHT PATH e-mail: [email protected] 20 tel.: 58 719 23 25; fax: 58 719 39 20 Pamukkale czyli bawełniana twierdza Pamukkale, or the Cotton Castle WYDAWCA: Marcin Ranuszkiewicz REDAKTOR NACZELNY: Jakub Milszewski DYREKTOR ARTYSTYCZNY: Michał Witucki OKOLICE SURROUNDINGS 26 GRAFIK: Katarzyna Gnacińska NAVIGATION „Muszkieterzy” z Placu Zbawiciela TŁUMACZENIE: Paulina Chojnowska, „Musketeers” from the Saviour Square Katarzyna Pastuszak 8 ZESPÓŁ REDAKCYJNY: Sylwia Gutowska, Agnieszka Mróz, Katarzyna Szewczyk GUST TASTE DZIAŁ REKLAMY: 32 Magdalena Słomka−Stażewska Epitafium dla ładnego swetra ([email protected]), Epitaph for a nice sweater Dagmara Zielińska NAWIGACJA ([email protected]), Natalia Zachalska ([email protected]) MODA Redakcja nie zwraca niezamówionych tekstów i mate- FASHION riałów redakcyjnych oraz nie ponosi odpowiedzialności 48 Chomisawa za treść nadesłanych ogłoszeń reklamowych. Redakcja zastrzega sobie prawo do redagowania i skracania tekstów. Chomisawa DRUK: Artdruk Zakład Poligraficzny w Kobyłce NA ZLECENIE / AT REQUEST PORT LOTNICZY AIRPORT 58 Latające Miss Flying Miss Mazowiecki Port Lotniczy Warszawa-Modlin Sp. z o.o. ul. gen. Wiktora Thommee 1a 65 74 05-102 Nowy Dwór Mazowiecki www.modlinairport.pl NASZ MAGAZYN MONITOROWANY PARTNERZY / PARTNERS JEST PRZEZ INSTYTUT MONITOROWANIA MEDIÓW FELLOW FELLOW TRAVELLER 10 TOWARZYSZ PODRÓŻY ENGLISH TEXT STARTS AT PAGE 14 Z JAJ Zatytułowanie tego wywiadu „Demoniczny golibroda” byłoby po pierwsze wtórne, po drugie nadużyciem. -

Martyna Mirecka Phd Thesis

"MONARCHY AS IT SHOULD BE"? BRITISH PERCEPTIONS OF POLAND-LITHUANIA IN THE LONG SEVENTEENTH CENTURY Martyna Mirecka A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 2014 Full metadata for this item is available in Research@StAndrews:FullText at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/6044 This item is protected by original copyright “Monarchy as it should be”? British perceptions of Poland-Lithuania in the long seventeenth century by Martyna Mirecka Submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History University of St Andrews September 2013 Abstract Early modern Poland-Lithuania figured significantly in the political perceptions of Europeans in the long seventeenth century – not only due to its considerable size and enormous commercial and military resources, but also, and just as importantly, due to its exceptional religious and political situation. This interest in Poland-Lithuania was shared by many Britons. However, a detailed examination of how Britons perceived Poland-Lithuania at that time and how they treated Poland-Lithuania in their political debates has never been undertaken. This thesis utilises a wide range of the previously neglected source material and considers the patterns of transmission of information to determine Britons’ awareness of Poland-Lithuania and their employment of the Polish-Lithuanian example in the British political discourse during the seventeenth century. It looks at a variety of geographical and historical information, English and Latin descriptions of Poland-Lithuania’s physical topography and boundaries, and its ethnic and cultural make-up presented in histories, atlases and maps, to establish what, where and who Poland-Lithuania was for Britons.