G Writing and Pseudo Script S, from Prehistory to Modern Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes

Signmaking, Chino-Latino Style: Concretismo and the Mimesis of Chinese Graphemes _______________________________________________ DAVID A. COLÓN TEXAS CHRISTIAN UNIVERSITY Concrete poetry—the aesthetic instigated by the vanguard Noigandres group of São Paulo, in the 1950s—is a hybrid form, as its elements derive from opposite ends of visual comprehension’s spectrum of complexity: literature and design. Using Dick Higgins’s terminology, Claus Clüver concludes that “concrete poetry has taken the same path toward ‘intermedia’ as all the other arts, responding to and simultaneously shaping a contemporary sensibility that has come to thrive on the interplay of various sign systems” (Clüver 42). Clüver is considering concrete poetry in an expanded field, in which the “intertext” poems of the 1970s and 80s include photos, found images, and other non-verbal ephemera in the Concretist gestalt, but even in limiting Clüver’s statement to early concrete poetry of the 1950s and 60s, the idea of “the interplay of various sign systems” is still completely appropriate. In the Concretist aesthetic, the predominant interplay of systems is between literature and design, or, put another way, between words and images. Richard Kostelanetz, in the introduction to his anthology Imaged Words & Worded Images (1970), argues that concrete poetry is a term that intends “to identify artifacts that are neither word nor image alone but somewhere or something in between” (n/p). Kostelanetz’s point is that the hybridity of concrete poetry is deep, if not unmitigated. Wendy Steiner has put it a different way, claiming that concrete poetry “is the purest manifestation of the ut pictura poesis program that I know” (Steiner 531). -

Access to Blissymbolics In

Access to Blissymbolics in ICT state-of-the-art and visions Mats Lundälv, DART, Sahlgrenska University Hospital, and BCI, Göteborg, Sweden Presented by Stephen van Tetzchner, ISAAC Research Symposium, Pittsburgh, USA, 2012 Introduction: Blissymbolics is, unlike most other graphical AAC systems, well suited for use on all technology levels, from no-tech, over low-tech, to current hi-tech ICT platforms. Blisymbols may be drawn by hand, in the sand, with paper and pen, or on a blackboard or whiteboard. In current practice we are however, as we are for all other symbol resources, heavily dependent on ICT support for practically managing and using Blissymbolics. It may be for setting up and printing symbol charts for low-tech use, or for writing documents or communicating remotely via email etc on computers and mobile devices. This presentation is an attempt to give an overview of the availability of Blissymbolics on current ICT platforms 2012, and some hints about what we can expect for the near future. Background: Blissymbolics was probably the first graphical AAC system to be supported on the emerging computer platforms in the early 1980:s; Talking BlissApple was one of the first pieces of AAC software developed for Apple II computers by Gregg Vanderheiden et al at Trace R&D Center, Madison Wisconsin USA. It was a break-through and was followed by a large number of Blissymbol AAC programs for the different computing platforms over the next decades. However, when the real expansion of the AAC technology came, with a number of commercially promoted pictorial systems such as PCS etc, Blissymbolics was largely dropping out of support on the dominating AAC software and hardware platforms. -

Pictograms: Purely Pictorial Symbols

toponymy course 10. Writing systems Ferjan Ormeling This chapter shows the semantic, phonetic and graphic aspects of language. It traces the development of the graphic aspects from Sumeria 3500BC, from logographic or ideographic via syllabic into alphabetic scripts resulting in a number of script families. It gives examples of the various scripts in maps (see underlined script names) and finally deals with combination of scripts on maps. 03/07/2011 1 Meaning, sound and looks What is the name? - Is it what it means? - Is it what it sounds? - Is it what it looks? 03/07/2011 2 Meaning: the semantic aspect As long as a name is what it means, both its sound and its looks (spelling) are only relevant as far as they support the meaning. The name ‘Nederland’ is wat it means to our neighbours: ‘Low country’. So they translate it for instance into ‘Pays- Bas’ (French) or Netherlands (English) or Niederlande (German), even though that does neither sound nor look like ‘Nederland’. To Romans and Italians, however, the names Qart Hadasht and Neapolis had never been what they meant (‘new towns’). So they became what they sounded: Carthago (to the Roman ear) and Napoli. 03/07/2011 3 Sound: the phonetic aspect As soon as a name is what it sounds, its meaning has become irrelevant. Its looks (spelling) then may or may not be adapted to its sound. The dominance of the phonetic aspect to a name (the ‘oral tradition’) allows the name to degenerate graphically. Eventually, the name may be adapted semantically to its perceived sound, through a process called ‘popular etymology’. -

The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized

American Journal of Applied Psychology 2017; 6(5): 88-92 http://www.sciencepublishinggroup.com/j/ajap doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 ISSN: 2328-5664 (Print); ISSN: 2328-5672 (Online) The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized Marcienne Martin ORACLE Laboratory, Observatory of Arts, Civilizations and Literatures, in Their Environment, University of Reunion Island, France Email address: [email protected] To cite this article: Marcienne Martin. The Language on the Internet, an Ancient Know-How Digitalized. American Journal of Applied Psychology. Vol. 6, No. 5, 2017, pp. 88-92. doi: 10.11648/j.ajap.20170605.11 Received: January 16, 2017; Accepted: January 25, 2017; Published: October 18, 2017 Abstract: The digital paradigm to which these new technologies (NTIC) belong is at the origin of particular linguistic practices. Internet is an innovator in this field. Indeed, its users want their written communications to be as fast as during oral exchanges; they will choose their knowledge to write on a saving in expressive type. Also wishing to transmit feelings and emotions, they will call upon an iconography, which uses the diacritics as material serving creation of logograms. This redundancy of a diverted punctuation of its original use, but being used “to punctuate” the speech by figurines translating the emotional state of the speaker, is a characteristic of this numerical space. Through the analysis of the corpus taken on the Internet and put in comparison with the hieroglyphic system introduced by Champollion Le Jeune [5] and the graphic evolution of some ideograms, it will be shown that it is always about the same used model, in which a key always initiates a semantic field, and that this process orders a reorganization of the objects of the world through a new scriptural writing. -

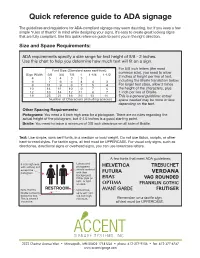

Quick Reference Guide to ADA Signage

Quick reference guide to ADA signage The guidelines and regulations for ADA-compliant signage may seem daunting, but if you keep a few simple “rules of thumb” in mind while designing your signs, it’s easy to create great looking signs that are fully compliant. Use this quick reference guide to point you in the right direction. Size and Space Requirements: ADA requirements specify a size range for text height of 5/8 - 2 inches. Use this chart to help you determine how much text will fit on a sign. For 5/8 inch letters (the most common size), you need to allow 2 inches of height per line of text, including the Braille translation below. For larger text sizes, allow 2 times the height of the characters, plus 1 inch per line of Braille. This is a general guideline; actual space needed may be more or less depending on the text. Other Spacing Requirements: Pictograms: You need a 6 inch high area for a pictogram. There are no rules regarding the actual height of the pictogram, but 4-4.5 inches is a good starting point. Braille: You need to leave a minimum of 3/8 inch clearance on all side of Braille. Text: Use simple, sans serif fonts, in a medium or bold weight. Do not use italics, scripts, or other hard-to-read styles. For tactile signs, all text must be UPPERCASE. For visual only signs, such as directories, directional signs or overhead signs, you can use lowercase letters. A few fonts that meet ADA guidelines: 6 inch high area Letters and with nothing in it pictograms except the should contrast pictogram. -

Application of Blissymbolics to the Non-Vocal Communicatively Handicapped

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1977 Application of Blissymbolics to the non-vocal communicatively handicapped Karen Lynn Jones The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, Karen Lynn, "Application of Blissymbolics to the non-vocal communicatively handicapped" (1977). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 1576. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/1576 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE APPLICATION OF BLISSYMBOLICS TO THE NON-VOCAL COMMUNICATIVELY HANDICAPPED by Karen L. Jones B.A., University of Montana, 1974 Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Communication Sciences and Disorders UNIVERSITY OF MONTANA 1977 Approved by: Chairman iBo^d of ^miners Deaw^ Gradua t^chool Date UMI Number; EP34649 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent on the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT IXMHtitian PUbMIng UMI EP34649 Copyright 2012 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. -

The Fundamental Rules of Blissymbolics: Creating New Blissymbolics Characters and Vocabulary

The fundamental rules of Blissymbolics: creating new Blissymbolics characters and vocabulary Blissymbolics Communication International (BCI) ¯ 2009-01-26 1 Introduction 1 2 Blissymbolics 2 3 Definitions 2 4 Graphic aspects of the language 4 5 Bliss-characters 7 6 Bliss-words 11 7 Indicators 16 8 Wordbuilding strategies for vocabulary extension 19 9 The Blissymbolics Development Process 22 10 Bibliography 26 11 The history of Blissymbol standardization 26 12 Figure 1: Summary of the Blissymbolics development process 29 13 Figure 2: Flow chart of the Blissymbolics development process 30 1.0 Introduction. This document describes the basic structure of the Blissymbolics language, and outlines both the rules necessary to be followed for creating new BCI Authorized Vocabulary, as well as procedures used for adopting that vocabulary. This reference document will guide anyone wishing to use the Blissymbolics language. Its purpose is to ensure consistency and maintain the integrity of Blissymbolics as an international language. The formal process for the development of Blissymbolics is outlined in clause 9. NOTE: A number of technical notes appear throughout the document in smaller type. These notes refer to a number of elements which are technical in nature, such as providing specific advice for font implementations (clause 4.3.6) or the need to keep the creation of new Bliss-characters to a minimum (clause 8.9). Many users of this document will not need to take these notes into account for purposes of teaching, but they are nonetheless important for vocabulary development work and do form a part of the official guidelines. 1.1 Target users. -

A STUDY of WRITING Oi.Uchicago.Edu Oi.Uchicago.Edu /MAAM^MA

oi.uchicago.edu A STUDY OF WRITING oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu /MAAM^MA. A STUDY OF "*?• ,fii WRITING REVISED EDITION I. J. GELB Phoenix Books THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS oi.uchicago.edu This book is also available in a clothbound edition from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS TO THE MOKSTADS THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS, CHICAGO & LONDON The University of Toronto Press, Toronto 5, Canada Copyright 1952 in the International Copyright Union. All rights reserved. Published 1952. Second Edition 1963. First Phoenix Impression 1963. Printed in the United States of America oi.uchicago.edu PREFACE HE book contains twelve chapters, but it can be broken up structurally into five parts. First, the place of writing among the various systems of human inter communication is discussed. This is followed by four Tchapters devoted to the descriptive and comparative treatment of the various types of writing in the world. The sixth chapter deals with the evolution of writing from the earliest stages of picture writing to a full alphabet. The next four chapters deal with general problems, such as the future of writing and the relationship of writing to speech, art, and religion. Of the two final chapters, one contains the first attempt to establish a full terminology of writing, the other an extensive bibliography. The aim of this study is to lay a foundation for a new science of writing which might be called grammatology. While the general histories of writing treat individual writings mainly from a descriptive-historical point of view, the new science attempts to establish general principles governing the use and evolution of writing on a comparative-typological basis. -

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 40

ONIX for Books Codelists Issue 40 23 January 2018 DOI: 10.4400/akjh All ONIX standards and documentation – including this document – are copyright materials, made available free of charge for general use. A full license agreement (DOI: 10.4400/nwgj) that governs their use is available on the EDItEUR website. All ONIX users should note that this is the fourth issue of the ONIX codelists that does not include support for codelists used only with ONIX version 2.1. Of course, ONIX 2.1 remains fully usable, using Issue 36 of the codelists or earlier. Issue 36 continues to be available via the archive section of the EDItEUR website (http://www.editeur.org/15/Archived-Previous-Releases). These codelists are also available within a multilingual online browser at https://ns.editeur.org/onix. Codelists are revised quarterly. Go to latest Issue Layout of codelists This document contains ONIX for Books codelists Issue 40, intended primarily for use with ONIX 3.0. The codelists are arranged in a single table for reference and printing. They may also be used as controlled vocabularies, independent of ONIX. This document does not differentiate explicitly between codelists for ONIX 3.0 and those that are used with earlier releases, but lists used only with earlier releases have been removed. For details of which code list to use with which data element in each version of ONIX, please consult the main Specification for the appropriate release. Occasionally, a handful of codes within a particular list are defined as either deprecated, or not valid for use in a particular version of ONIX or with a particular data element. -

Of ISO/IEC 10646 and Unicode

ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 N2114 Title: Graphic representation of the Roadmap to the SMP, Plane 1 of the UCS Source: Ad hoc group on Roadmap Status: Expert contribution Date: 1999-09-15 Action: For confirmation by ISO/IEC JTC1/SC2/WG2 Replaces: N2046 The following tables comprise a real-size map of Plane 1, the SMP (Secondary Multilingual Plane) of the UCS (Universal Character Set). To print the HTML document it may be necessary to set the print percentage to 90% as the tables are wider than A4 or US Letter paper. The tables are formatted to use the Times font. The following conventions are used in the table to help the user identify the status of (colours can be seen in the online version of this document, http://www.dkuug.dk/jtc1/sc2/wg2/docs/n2114.pdf): Bold text indicates an allocated (i.e. published) character collection (none as yet in Plane 1). (Bold text between parentheses) indicates scripts which have been accepted for processing toward inclusion in the standard. (Text between parentheses) indicates scripts for which proposals have been submitted to WG2 or the UTC. ¿Text beween question marks? indicates scripts for which detailed proposals have not yet been written. ??? in a block indicates that no suggestion has been made regarding the block allocation. NOTE: With regard to the revision practice employed in this document, when scripts are actually proposed to WG2 or to the UTC, the practice is to "front" them in the zones to which they are tentatively allocated, and to adjust the block size with regard to the allocation proposed. -

ICA Course on Toponymy

S10: Writing systems 2. SCRIPTS, THE GRAPHICS OF LANGUAGE <previous - next> The cradle of most of the modern phonographic scripts is the Middle East. The oldest known Sumerian and Home Egyptian pictographic inscriptions considered to be scripts date from the 4th millennium BC. | Self study : Scripts were developed to extend man’s scope and range. Writing Systems | Pictograms: purely pictorial symbols. Contents | Pictograms were used to represent the concepts (ideograms) or words (logograms) they represented. Intro | 1.Meaning, Ultimately, logograms develop into phonograms, in which the sound value (phoneme) of mono- sound & looks (a/b/c) syllabic words is attached to the symbols representing these words. | 2.Scripts | Finally the syllabic script develops into an alphabetic script in which symbols represent single 3.Script phonemes instead of syllables. development | 4.Division Universal sequence from purely pictorial representation (pictograms) to sets of abstracted sound- | 5.Basic unit representing symbols (phonograms). of writing Pictograms convey meaning without intervention of sound values; there may be a symbol meaning ‘town’, | ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ irrespective of what the word for ‘town’, ‘river’ or ‘mountain’ sounds like, and thus 6.Logograms | regardless of any specific language. Such a symbol is named a logogram (pictogram for a specific word). 7.Ideographic The advantage of logograms is their universal applicability – because they are language-independent – but and they have the obvious disadvantage that there must be a separate symbol for every word. logographic scripts | All complete writing systems the world has ever known, do effectively contain both logograms and 8.Syllabic phonograms. As purely pictorial ‘proto-scripts’ develop into ‘scripts’ or writing systems, naturally drawn scripts pictograms are stylised and augmented with drawings for abstract phenomena (hence called ideograms), | 9.Alphabetic and will ultimately contain logograms for all basic words of a specific language. -

Pictograms and Visual Cognition

Damian Goidich Professor Diane Zeeuw New Visual Studies April 5, 2011 Pictograms and Visual Cognition Pictograms are a unique addition to the history of our pictorial language. Initially devised as a 20th century solution to the complications created by the globalization of mass transit, communication and travel, their effectiveness at transmitting messages, commands and direction through a distinct set of graphic shapes, symbols and colors has revolutionized how we visually interpret images and communicate on an international scale in the 21st century. Pictograms as a visual form of communication have their roots in ancient civilizations dating back to the fourth millennium BCE. The earliest use of pictograms as a form of communication or “writing” is generally attributed to the Sumerian civilization circa 3500 BCE (Fig. 1). While little is known of the details surrounding their culture, archaeological evidence suggests that their use of cuneiforms was a specialized form of object representation used to record, amongst other things, economic transactions such as the buying and selling of livestock and foodstuffs (Frutiger 119-20). This form of communication through images has continued virtually uninterrupted down through the historical timeline, being well documented in the cultures of Egypt, China, the Middle East, the Mayan and Aztec civilizations of Mesoamerica, and throughout Medieval Europe. The 20th century brought about a tremendous acceleration in the fields of technology, most evident in the invention and proliferation of the automobile which effected both national and international commerce. This led to the development of an extensive grid of roads and highways necessary for the accommodation of the burgeoning mobile culture.