Degruyter Opar Opar-2020-0135 155..176 ++

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

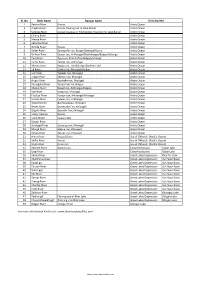

List of Rivers of Mongolia

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

The Influence of Climatic Change and Human Activity on Erosion Processes in Sub-Arid Watersheds in Southern East Siberia

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 17, 3181–3193 (2003) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hyp.1382 The influence of climatic change and human activity on erosion processes in sub-arid watersheds in southern East Siberia Leonid M. Korytny,* Olga I. Bazhenova, Galina N. Martianova and Elena A. Ilyicheva Institute of Geography, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1 Ulanbatorskaya St., Irkutsk, 664033, Russia Abstract: A LUCIFS model variant is presented that represents the influence of climate and land use change on fluvial systems. The study considers trends of climatic characteristics (air temperature, annual precipitation totals, rainfall erosion index, aridity and continentality coefficients) for the steppe and partially wooded steppe watersheds of the south of East Siberia (the Yenisey River macro-watershed). It also describes the influence of these characteristics on erosion processes, one indicator of which is the suspended sediment yield. Changes in the river network structure (the order of rivers, lengths, etc.) as a result of agricultural activity during the 20th century are investigated by means of analysis of maps of different dates for one of the watersheds, that of the Selenga River, the biggest tributary of Lake Baikal. The study reveals an increase of erosion process intensity in the first two-thirds of the century in the Selenga River watershed and a reduction of this intensity in the last third of the century, both in the Selenga River watershed and in most of the other watersheds of the study area. Copyright 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. KEY WORDS LUCIFS; Yenisey watershed; fluvial system; climate change; land use change; river network structure; erosion processes. -

Favorite Winter Russia Siberia + Ice Safari of Lake Baikal

OE08FSIBFEBMAR / Update, 29/11/19 FAVORITE WINTER RUSSIA SIBERIA + ICE SAFARI OF LAKE BAIKAL 08 HARI ( IKT – IKT ) | 01 NEGARA | CATHAY PACIFIC + SIBERIA AIRLINES Keberangkatan: 12, 19, 26 FEB / 04, 11, 18 MAR 2020 Termasuk: Travel Insurance, 07 Malam di Siberia, Peschanaya Bay, Olkhon Island, Ogoy Island, Cape Khoboy, Buryats Village HARI 01: JAKARTA – HONG KONG – IRKUTSK mengunjungi White Buddhist Stupa yang didedikasikan ( flight tba) untuk Dewi Dakini. Dilanjutkan menuju ke Khuzhir di Pulau Hari ini berkumpul di Bandara Soekarno-Hatta untuk Olkhon untuk Anda beristirahat dan bermalam. bersama-sama memulai perjalanan menuju Irkutsk, Rusia. Setibanya di kota ini yang merupakan salah satu kota terbesar HARI 05: KHUZIR - CAPE KHOBOY EXCURSION – di wilayah Siberia yang terkenal dengan sebutan “Paris of Siberia”, KHUZHIR Anda akan langsung diantar ke hotel untuk beristirahat. (termasuk Santap Pagi, Siang, Malam ) Hari ini dengan berkendara mobil 4WD-UAZ, Anda akan HARI 02: IRKUTSK – LISTVYANKA diajak berorientasi dengan mengunjungi bagian paling utara (termasuk Santap Pagi, Siang, Malam ) dari Pulau Olkhon yang bernama Khoboy Cape, tempat ini Pagi ini Anda akan diajak menuju ke kota Listvyanka untuk merupakan pertemuan antara bagian danau kecil dan besar. diajak city tour mengunjungi Aquarium of Baikal Seal, Baikal Anda akan disuguhkan dengan pemandangan yang sangat Museum mengenai sejarah Danau Baikal, Museum of indah dengan mengunjungi Ice Grottoes, Shaman Rock yang Wooden Architecture "Taltsi”. Dan akan mencoba makanan dulu dikenal sebagai “Kuil Batu” merupakan tempat suci bagi khas Ikan Omul Asap di Fish Market. Kemudian dengan para Shamans. menggunakan kursi gantung (jika cuaca memungkinkan) HARI 06: OLKHON ISLAND – UST ORDA - IRKUTSK diajak menikmati panorama keindahan Danau Baikal dari (termasuk Santap Pagi, Siang, Malam ) ketinggian Observation Point. -

Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi'nin Coğrafyasi

International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE) To Cite This Article: Can, R. R. (2021). Geography of the Trans-Baykal (Russia) region. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE), 43, 365-385. Submitted: October 07, 2020 Revised: November 01, 2020 Accepted: November 16, 2020 GEOGRAPHY OF THE TRANS-BAYKAL (RUSSIA) REGION Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi’nin Coğrafyası Reyhan Rafet CAN1 Öz Zabaykalskiy Kray (Bölge) olarak isimlendirilen saha adını Rus kâşiflerin ilk kez 1640’ta karşılaştıkları Daur halkından alır. Rusçada Zabaykalye, Balkal Gölü’nün doğusu anlamına gelir. Trans-Baykal Bölgesi, Sibirya'nın en güneydoğusunda, doğu Trans-Baykal'ın neredeyse tüm bölgesini işgal eder. Bölge şiddetli iklim koşulları; birçok mineral ve hammadde kaynağı; ormanların ve tarım arazilerinin varlığı ile karakterize edilir. Rusya Federasyonu'nun Uzakdoğu Federal Bölgesi’nin bir parçası olan on bir kurucu kuruluşu arasında bölge, alan açısından altıncı, nüfus açısından dördüncü, bölgesel ürün üretimi açısından (GRP) altıncı sıradadır. Bölge topraklarından geçen Trans-Sibirya Demiryolu yalnızca Uzak Doğu ile Rusya'nın batı bölgeleri arasında bir ulaşım bağlantısı değil, aynı zamanda Avrasya geçişini sağlayan küresel altyapının da bir parçasıdır. Bölgenin üretim yapısında sanayi, tarım ve ulaşım yüksek bir paya sahiptir. Bu çalışmada Trans-Baykal Bölgesi’nin fiziki, beşeri ve ekonomik coğrafya özellikleri ele alınmıştır. Trans-Baykal Bölgesinin coğrafi özelliklerinin yanı sıra, ekonomik ve kültürel yapısını incelenmiştir. Bu kapsamda konu ile ilgili kurumsal raporlardan ve alan araştırmalarından yararlanılmıştır. Bu çalışma sonucunda 350 yıldan beri Rus gelenek, kültür ve yaşam tarzının devam ettiği, farklı etnik grupların toplumsal birliği sağladığı, yer altı kaynaklarının bölge ekonomisi için yüzyıllardır olduğu gibi günümüzde de önem arz ettiği, coğrafyasının halkın yaşam şeklini belirdiği sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Siberia & the Russian Far East

SIBERIA & THE RUSSIAN FAR EAST JULY 17 – AUGUST 1, 2019 TOUR LEADER: DR MATTHEW DAL SANTO SIBERIA & THE Overview RUSSIAN FAR EAST Embark on the tour of a lifetime to one of the world's last great travel Tour dates: July 17 – August 1, 2019 frontiers. This 16-day tour reveals the cultural and geographical wonders of Siberia and the Russian Far East. Tour leader: Dr Matthew Dal Santo We begin in Irkutsk, a former Cossack settlement forever linked to the Tour Price: $16,975 per person, twin share memory of the immortal ‘Decembrists’ – public-minded nobles who, exiled to Siberia for their part in an 1825 rebellion against the Tsar, recreated Single Supplement: $1,590 for sole use of with their wives the cultural and artistic life of St Petersburg for the benefit double room of Siberia’s rough frontiersmen. From Irkutsk we then travel to the superbly beautiful Lake Baikal, the world’s largest (by volume: Baikal Booking deposit: $500 per person contains about a fifth of all the world’s fresh water), oldest and deepest lake to spend two nights on Olkhon Island, which is sacred to the Recommended airline: Korean Airlines indigenous Buryat people and widely regarded as Baikal’s ‘jewel’ for its otherworldly beauty. Maximum places: 20 Taking the legendary Trans-Siberian Railway along Baikal’s rugged Itinerary: Irkutsk (2 nights), Lake Baikal (2 southern shore, we arrive in Ulan Ude, a culturally Mongolian town that is nights), Irkutsk (1 night), Ulan Ude (3 nights), the centre of Russian Buddhism with its centuries of close links with Tibet, Khabarovsk (1 night), Petropavlovsk- as well as a stronghold of the so-called ‘Old Believers’, a long-persecuted Kamchatsky (4 nights), Vladivostok (2 nights) Orthodox sect who have preserved in Siberia’s remote wooded valleys a centuries-old culture that includes a rich repertoire of songs of exile. -

Download Download

© Entomologica Fennica. 15 June 2003 Contribution to the scythridid fauna of southern Buryatia, with description of seven new species (Lepidoptera: Scythrididae) Kari Nupponen Nupponen, K. 2003: Contribution to the scythridid fauna of southern Buryatia, with description of seven new species (Lepidoptera: Scythrididae). — Entomol. Fennica 14: 25–45. A list of 26 species embracing 673 specimens of the family Scythrididae collected during 13.–29.VI.2002 from southern Buryatia is presented. Seven new species are described: Scythris erinacella sp. n., S. gorbunovi sp. n., S. hamardabanica sp. n., S. malozemovi sp. n., S. ninae sp. n., S. potatorella sp. n. and S. sinevi sp. n. Two unknown species are mentioned but not described because only females are available. In addition, S. penicillata Chrétien, 1900 is reported as new for Russia, S. emichi (Anker, 1870) as new for the Asiatic part of Russia and seven further species as new for the Baikal region. The known distribution range of each species is given as well as further notes on some poorly known taxa. Kari Nupponen, Miniatontie 1 B 9, FIN-02360 Espoo, Finland Received 30 October 2002, accepted 21 January 2003 1. Introduction & Liòka 1996, Sinev 2001) concern occasionally collected single specimens, and no systematic in- The Republic of Buryatia is located on the southern vestigations of scythridids have been made in the and southeastern shores of Lake Baikal. Character- region. The present article is based on material istic features of the southern part of that region are collected by the author during 13.–29.VI.2002 in mountain ranges: East Sayan Mountains in the west southern Buryatia. -

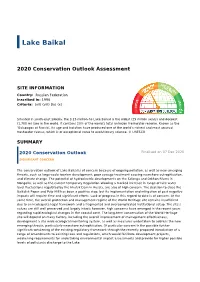

2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment

IUCN World Heritage Outlook: https://worldheritageoutlook.iucn.org/ Lake Baikal - 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment Lake Baikal 2020 Conservation Outlook Assessment SITE INFORMATION Country: Russian Federation Inscribed in: 1996 Criteria: (vii) (viii) (ix) (x) Situated in south-east Siberia, the 3.15-million-ha Lake Baikal is the oldest (25 million years) and deepest (1,700 m) lake in the world. It contains 20% of the world's total unfrozen freshwater reserve. Known as the 'Galapagos of Russia', its age and isolation have produced one of the world's richest and most unusual freshwater faunas, which is of exceptional value to evolutionary science. © UNESCO SUMMARY 2020 Conservation Outlook Finalised on 07 Dec 2020 SIGNIFICANT CONCERN The conservation outlook of Lake Baikal is of concern because of ongoing pollution, as well as new emerging threats, such as large-scale tourism development, poor sewage treatment causing nearshore eutrophication, and climate change. The potential of hydroelectric developments on the Selenga and Orkhon Rivers in Mongolia, as well as the current temporary Regulation allowing a marked increase in range of lake water level fluctuations regulated by the Irkutsk Dam in Russia, are also of high concern. The decision to close the Baikalsk Paper and Pulp Mill has been a positive step, but its implementation and mitigation of past negative impacts will require time and significant efforts. Lack of progress in this regard to date is of concern. At the same time, the overall protection and management regime of the World Heritage site remains insufficient due to an inadequate legal framework and a fragmented and overcomplicated institutional setup. -

Sustainable Water Management in the Selenga-Baikal Basin

Sustainable Water Management in the Selenga-Baikal Basin Integrated Environmental Assessment for a Transboundary Watershed with Multiple Stressors Contact Integrated Water Resources Management – Model Region Mongolia – If you have any questions or suggestions, please do not hesitate to contact us: Dr. Daniel Karthe | [email protected] Philipp Theuring | [email protected] Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research, Magdeburg, Germany Acad. Prof. Dr. Nikolay Kasimov | [email protected] Dr. Sergey Chalov | [email protected] Lomonosov Moscow State University, Russia For further information and contacts, please refer to www.iwrm-momo.de Project Profi le Sustainable Water Management in the Selenga-Baikal Basin Integrated Environmental Assessment for a Transboundary Watershed with Multiple Stressors August 2014 Publisher: Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research (UFZ) Moscow Lomonosov State University Editors: Dr. Daniel Karthe | Dr. Sergey Chalov Layout: perner&schmidt werbung und design gmbh Sponsors: International Bureau of the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) Russian Geographical Society Links: www.ufz.de www.eng.geogr.msu.ru SELENGA-BAIKAL PROJECT Lake Baikal Page 2 SELENGA-BAIKAL PROJECT Table of Contents/Partners Table of Contents Page 1 Introduction . 4 2 Hydrochemical Monitoring in the Selenga-Baikal Basin . 5 3 Planning IWRM in the Kharaa River Model Region . 6 4 A Monitoring Concept for the Selenga-Baikal Basin . 7 5 Selected Publications . 8 Contact . 9 Partners Helmholtz Centre for Environmental Research Lomonosov Moscow State University Associated partners are the Mongolian Academy of Sciences (Institutes of Geograpy and Geoecology), the Russian Academy of Sciences (Institute of Water Problems, the Joint Russian-Mongolian Complex Biological Expedition) and the Center for Environmental Systems Research of Kassel University, Germany. -

Kat Rus3.Pdf

1 2 “Art-Travel” DMC successfully operates on a travel market from 2003. Our Company is a member of an Advisory Committee in the National Agency of tourism in Italy, club “Hungary”, organized by the Office of the Adviser for tourism of Hungary in Russia and “Malta” club. “Art-Travel” is a participant of the road show in India “Welcome to St. Petersburg” of Russian Committee for Tourism and Russian Travel Industry Union. Also we are active member of international exhi- bitions including WTM in London and ITB in Berlin. Our staff understands the various mentality about and preferences of guests from different countries, and pro- vides in accordance with every need the wide range of services for any kind of trips, cruises and events: • Accommodation at hotels of all categories • High qualified guides and interpreter’s services, including a rare languages for Russia area (as Serbian, Dutch, Croatian, Estonian) • Transportation by coaches and minivans of standard/business/deluxe class: o For excursions o For transfers o Car with driver/for rent • Tours all over Russia: o Around Golden Ring, Baikal Lake and Siberia, Kazan, river cruises with stops in the most ancient Russian towns, Sochi, Karelia and other good-known places. o Full-days excursions from Moscow and St. Petersburg for Pskov, Novgorod, Sergiev Posad, etc. • Comfort services for VIP-tours and Business-class tours in St. Petersburg and Moscow • MICE: o Organizations of theme events, corporate training and team-building, corporate receptions, parties o Conference venues, facilities and equipment for workshops, conferences, seminars • Unique variety of tours and original excursions for groups and individual travelers • Rail and airway tickets services • Visa Support We are the friendly team of professionals and like our work and people, so are pleased to offer the best decision for any kind of inquiries. -

The Impact of Tourism on Traditional Siberian Culture Grace Elizabeth Michaels

)ORULGD6WDWH8QLYHUVLW\/LEUDULHV 2020 Conversations on the Top Steppe: The Impact of Tourism on Traditional Siberian Culture Grace Elizabeth Michaels Follow this and additional works at DigiNole: FSU's Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected] CONVERSATIONS ON THE TOP STEPPE 1 THE FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AND PUBLIC POLICY CONVERSATIONS ON THE TOP STEPPE: THE IMPACT OF TOURISM ON TRADITIONAL SIBERIAN CULTURE By GRACE MICHAELS A Thesis submitted to the Department of International Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with Honors in the Major Degree Awarded: Spring, 2020 CONVERSATIONS ON THE TOP STEPPE 2 The members of the Defense Committee approve the thesis of Grace Michaels defended on April 20, 2020. Nina Efimov ______________________________ Dr. Nina Efimov Thesis Director ______________________________ Dr. Whitney Bendeck Committee Member ______________________________ Dr. Portia Campos Outside Committee Member CONVERSATIONS ON THE TOP STEPPE 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT 4 INSPIRATION, PURPOSE 5 BACKGROUND INFORMATION 7 METHODOLOGY 11 LIMITATIONS, EXPLANATION 13 TESTIMONY 16 DISCUSSION AND ANALYSIS 55 THOUGHTS MOVING FORWARD 66 BIBLIOGRAPHY 69 APPENDIX A 73 APPENDIX B 76 CONVERSATIONS ON THE TOP STEPPE 4 ABSTRACT Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, inbound tourism spread across Russia. The small economy of Olkhon Island, located within Lake Baikal, was soon dependent on a rapidly expanding tourism industry. Shamanism, the dominant religion on the island, and native Buryat culture were unlike anything the majority of tourists had ever experienced. Religious and cultural tourism soon became very popular, and very profitable. As there is currently very little research on the topic, this project aims to serve as a pilot examination of the impact of the tourism industry on shamanism and native Buryat culture. -

Adventures In

Adventures in SiberiaHop aboard the Trans-Siberian Railway to experience a vast region rich in history, culture and natural beauty BY BENJAMIN MUSACHIO Mention “Siberia,” and many immediately think of a vast and inhospitable arctic exile. But the sprawling region belonging to Russia, which stretches southward from the Arctic Ocean all the way to the national borders of Mongolia and China, today offers a variety of exotic cultural and natural treasures that are quite enticing for the adventurous traveler. nless the prospect of subzero While the list of possible stops is rich in history, from its founding in Utemperatures is appealing, Siberia is on the main train line numbers in the 1723 under Peter the Great to the post- best experienced during the summer. dozens, here is a handful you won’t Soviet era, initiated by Russian President For travelers with a few weeks to spare, want to miss. Boris Yeltsin, a Yekaterinburg local. taking the Trans-Siberian Railway is the Lakes, fountains and wide promenades ideal way to experience the richness of Yekaterinburg make the city center especially the region. For the full impact, embark welcoming to pedestrians. from Moscow, then ride the train About 1,000 miles (1,700 kilometers) Your first stop should be the all the way to the end of the line in into your journey, plan to spend a memorial complex erected in the Vladivostok. Totaling more than 5,500 day or two in Yekaterinburg, known early 2000s on the execution site of miles (about 8,850 kilometers), the as the gateway to Siberia.