The Nature Conservation of Baikal Region: Special Natural Protected Areas System in Three Environmental Models

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pinus Cembra

Pinus cembra Pinus cembra in Europe: distribution, habitat, usage and threats G. Caudullo, D. de Rigo Arolla or Swiss stone pine (Pinus cembra L.) is a slow-growing, long lived conifer that grows at high altitudes (up to the treeline) with continental climate and is able to resist to very low winter temperature. It has large edible seeds which are dispersed principally by the European nutcracker. The timber is strong and of good quality but it is not a commercially important species because of its slow growth rate and frequent contorted shape. This pine is principally used to protect slopes and valleys against avalanches and soil erosion. In alpine habitats it is threatened principally by tourism development, even if the recent reduction of mountain pasture activities is allowing this pine to return in many areas. Pinus cembra L., known as Arolla pine or Swiss stone pine, is a slow growing, small to medium-sized evergreen conifer (10- Frequency 12 m height, occasionally 20-25 m), which can live up to 1000 < 25% 25% - 50% 1-5 years . The crown is densely conical when young, becoming 50% - 75% cylindrical and finally very open6. It grows commonly in a curved > 75% Chorology or contorted shape, but in protected areas can grow straight and Native to considerable sizes. Needles are in fascicles of five, 5-9 cm long1, 7. Arolla pine is a monoecious species and the pollination is driven by wind3. Seed cones appear after 40-60 years, they Seed cones are purplish in colour when maturing. are 4-8 cm long and mature in 2 years3, 6. -

List of Rivers of Mongolia

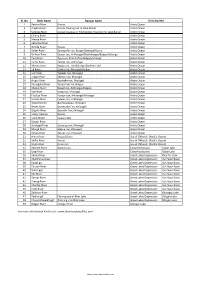

Sl. No River Name Russian Name Draining Into 1 Yenisei River Russia Arctic Ocean 2 Angara River Russia, flowing out of Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 3 Selenge River Сэлэнгэ мөрөн in Sükhbaatar, flowing into Lake Baikal Arctic Ocean 4 Chikoy River Arctic Ocean 5 Menza River Arctic Ocean 6 Katantsa River Arctic Ocean 7 Dzhida River Russia Arctic Ocean 8 Zelter River Зэлтэрийн гол, Bulgan/Selenge/Russia Arctic Ocean 9 Orkhon River Орхон гол, Arkhangai/Övörkhangai/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 10 Tuul River Туул гол, Khentii/Töv/Bulgan/Selenge Arctic Ocean 11 Tamir River Тамир гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 12 Kharaa River Хараа гол, Töv/Selenge/Darkhan-Uul Arctic Ocean 13 Eg River Эгийн гол, Khövsgöl/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 14 Üür River Үүрийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 15 Uilgan River Уйлган гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 16 Arigiin River Аригийн гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 17 Tarvagatai River Тарвагтай гол, Bulgan Arctic Ocean 18 Khanui River Хануй гол, Arkhangai/Bulgan Arctic Ocean 19 Ider River Идэр гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 20 Chuluut River Чулуут гол, Arkhangai/Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 21 Suman River Суман гол, Arkhangai Arctic Ocean 22 Delgermörön Дэлгэрмөрөн, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 23 Beltes River Бэлтэсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 24 Bügsiin River Бүгсийн Гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 25 Lesser Yenisei Russia Arctic Ocean 26 Kyzyl-Khem Кызыл-Хем Arctic Ocean 27 Büsein River Arctic Ocean 28 Shishged River Шишгэд гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 29 Sharga River Шарга гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 30 Tengis River Тэнгис гол, Khövsgöl Arctic Ocean 31 Amur River Russia/China -

Lake Baikal Russian Federation

LAKE BAIKAL RUSSIAN FEDERATION Lake Baikal is in south central Siberia close to the Mongolian border. It is the largest, oldest by 20 million years, and deepest, at 1,638m, of the world's lakes. It is 3.15 million hectares in size and contains a fifth of the world's unfrozen surface freshwater. Its age and isolation and unusually fertile depths have given it the world's richest and most unusual lacustrine fauna which, like the Galapagos islands’, is of outstanding value to evolutionary science. The exceptional variety of endemic animals and plants make the lake one of the most biologically diverse on earth. Threats to the site: Present threats are the untreated wastes from the river Selenga, potential oil and gas exploration in the Selenga delta, widespread lake-edge pollution and over-hunting of the Baikal seals. However, the threat of an oil pipeline along the lake’s north shore was averted in 2006 by Presidential decree and the pulp and cellulose mill on the southern shore which polluted 200 sq. km of the lake, caused some of the worst air pollution in Russia and genetic mutations in some of the lake’s endemic species, was closed in 2009 as no longer profitable to run. COUNTRY Russian Federation NAME Lake Baikal NATURAL WORLD HERITAGE SERIAL SITE 1996: Inscribed on the World Heritage List under Natural Criteria vii, viii, ix and x. STATEMENT OF OUTSTANDING UNIVERSAL VALUE The UNESCO World Heritage Committee issued the following statement at the time of inscription. Justification for Inscription The Committee inscribed Lake Baikal the most outstanding example of a freshwater ecosystem on the basis of: Criteria (vii), (viii), (ix) and (x). -

The Influence of Climatic Change and Human Activity on Erosion Processes in Sub-Arid Watersheds in Southern East Siberia

HYDROLOGICAL PROCESSES Hydrol. Process. 17, 3181–3193 (2003) Published online in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI: 10.1002/hyp.1382 The influence of climatic change and human activity on erosion processes in sub-arid watersheds in southern East Siberia Leonid M. Korytny,* Olga I. Bazhenova, Galina N. Martianova and Elena A. Ilyicheva Institute of Geography, Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 1 Ulanbatorskaya St., Irkutsk, 664033, Russia Abstract: A LUCIFS model variant is presented that represents the influence of climate and land use change on fluvial systems. The study considers trends of climatic characteristics (air temperature, annual precipitation totals, rainfall erosion index, aridity and continentality coefficients) for the steppe and partially wooded steppe watersheds of the south of East Siberia (the Yenisey River macro-watershed). It also describes the influence of these characteristics on erosion processes, one indicator of which is the suspended sediment yield. Changes in the river network structure (the order of rivers, lengths, etc.) as a result of agricultural activity during the 20th century are investigated by means of analysis of maps of different dates for one of the watersheds, that of the Selenga River, the biggest tributary of Lake Baikal. The study reveals an increase of erosion process intensity in the first two-thirds of the century in the Selenga River watershed and a reduction of this intensity in the last third of the century, both in the Selenga River watershed and in most of the other watersheds of the study area. Copyright 2003 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. KEY WORDS LUCIFS; Yenisey watershed; fluvial system; climate change; land use change; river network structure; erosion processes. -

Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi'nin Coğrafyasi

International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE) To Cite This Article: Can, R. R. (2021). Geography of the Trans-Baykal (Russia) region. International Journal of Geography and Geography Education (IGGE), 43, 365-385. Submitted: October 07, 2020 Revised: November 01, 2020 Accepted: November 16, 2020 GEOGRAPHY OF THE TRANS-BAYKAL (RUSSIA) REGION Trans-Baykal (Rusya) Bölgesi’nin Coğrafyası Reyhan Rafet CAN1 Öz Zabaykalskiy Kray (Bölge) olarak isimlendirilen saha adını Rus kâşiflerin ilk kez 1640’ta karşılaştıkları Daur halkından alır. Rusçada Zabaykalye, Balkal Gölü’nün doğusu anlamına gelir. Trans-Baykal Bölgesi, Sibirya'nın en güneydoğusunda, doğu Trans-Baykal'ın neredeyse tüm bölgesini işgal eder. Bölge şiddetli iklim koşulları; birçok mineral ve hammadde kaynağı; ormanların ve tarım arazilerinin varlığı ile karakterize edilir. Rusya Federasyonu'nun Uzakdoğu Federal Bölgesi’nin bir parçası olan on bir kurucu kuruluşu arasında bölge, alan açısından altıncı, nüfus açısından dördüncü, bölgesel ürün üretimi açısından (GRP) altıncı sıradadır. Bölge topraklarından geçen Trans-Sibirya Demiryolu yalnızca Uzak Doğu ile Rusya'nın batı bölgeleri arasında bir ulaşım bağlantısı değil, aynı zamanda Avrasya geçişini sağlayan küresel altyapının da bir parçasıdır. Bölgenin üretim yapısında sanayi, tarım ve ulaşım yüksek bir paya sahiptir. Bu çalışmada Trans-Baykal Bölgesi’nin fiziki, beşeri ve ekonomik coğrafya özellikleri ele alınmıştır. Trans-Baykal Bölgesinin coğrafi özelliklerinin yanı sıra, ekonomik ve kültürel yapısını incelenmiştir. Bu kapsamda konu ile ilgili kurumsal raporlardan ve alan araştırmalarından yararlanılmıştır. Bu çalışma sonucunda 350 yıldan beri Rus gelenek, kültür ve yaşam tarzının devam ettiği, farklı etnik grupların toplumsal birliği sağladığı, yer altı kaynaklarının bölge ekonomisi için yüzyıllardır olduğu gibi günümüzde de önem arz ettiği, coğrafyasının halkın yaşam şeklini belirdiği sonucuna varılmıştır. -

Forest Vegetation Dynamics Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Relation to the Climate Change in Southern Transbaikalia, Russia

ALS-00015; No of Pages 6 Achievements in the Life Sciences xxx (2014) xxx–xxx Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Achievements in the Life Sciences journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/als Forest Vegetation Dynamics Along an Altitudinal Gradient in Relation to the Climate Change in Southern Transbaikalia, Russia Irina V. Kozyr ⁎ Baikalsky State Natural Biosphere Reserve, 34 Krasnogvardeyskaya Street, Tankhoy, Kabansky District, Buryatia Republic, 671220, Russia Sokhondinsky State Natural Biosphere Reserve, 1 Cherkasova Street, Kyra, Zabaikalsky Region 674250, Russia article info abstract Available online xxxx In this study, we examined the response forest dynamics (since 1982) on Sokhondo Mountain (2500 m a.s.l.) under climate change in Transbaikalia (southeast of Lake Baikal, Russia) over the Keywords: last 60 years, using geobotanical and climate long-term monitoring as important tools to assess Forest vegetation the effect of climate change on forest dynamics. We found that changes in ecosystems along an Climate change altitudinal gradient indicated that climate had changed in the direction of warming and Long-term monitoring aridization (drought). This supposition was also confirmed by analyses of regional climate data Geobotanical sample plots over the last 60 years, which showed an increase in air temperature of 1.8 °С and a decrease in at- Sokhondinsky reserve mospheric precipitation of more than 100 mm. Forest vegetation along an altitudinal gradient Transbaikalia demonstrates various sensitivities to these effects. We found that the most stable forest vegetation types were the cedar–larch forests of the upper forest belt and the cedar subalpine forests. The least stable were the larch forests and pine forests of the lower forest belt. -

Subject of the Russian Federation)

How to use the Atlas The Atlas has two map sections The Main Section shows the location of Russia’s intact forest landscapes. The Thematic Section shows their tree species composition in two different ways. The legend is placed at the beginning of each set of maps. If you are looking for an area near a town or village Go to the Index on page 153 and find the alphabetical list of settlements by English name. The Cyrillic name is also given along with the map page number and coordinates (latitude and longitude) where it can be found. Capitals of regions and districts (raiony) are listed along with many other settlements, but only in the vicinity of intact forest landscapes. The reader should not expect to see a city like Moscow listed. Villages that are insufficiently known or very small are not listed and appear on the map only as nameless dots. If you are looking for an administrative region Go to the Index on page 185 and find the list of administrative regions. The numbers refer to the map on the inside back cover. Having found the region on this map, the reader will know which index map to use to search further. If you are looking for the big picture Go to the overview map on page 35. This map shows all of Russia’s Intact Forest Landscapes, along with the borders and Roman numerals of the five index maps. If you are looking for a certain part of Russia Find the appropriate index map. These show the borders of the detailed maps for different parts of the country. -

Download Download

© Entomologica Fennica. 15 June 2003 Contribution to the scythridid fauna of southern Buryatia, with description of seven new species (Lepidoptera: Scythrididae) Kari Nupponen Nupponen, K. 2003: Contribution to the scythridid fauna of southern Buryatia, with description of seven new species (Lepidoptera: Scythrididae). — Entomol. Fennica 14: 25–45. A list of 26 species embracing 673 specimens of the family Scythrididae collected during 13.–29.VI.2002 from southern Buryatia is presented. Seven new species are described: Scythris erinacella sp. n., S. gorbunovi sp. n., S. hamardabanica sp. n., S. malozemovi sp. n., S. ninae sp. n., S. potatorella sp. n. and S. sinevi sp. n. Two unknown species are mentioned but not described because only females are available. In addition, S. penicillata Chrétien, 1900 is reported as new for Russia, S. emichi (Anker, 1870) as new for the Asiatic part of Russia and seven further species as new for the Baikal region. The known distribution range of each species is given as well as further notes on some poorly known taxa. Kari Nupponen, Miniatontie 1 B 9, FIN-02360 Espoo, Finland Received 30 October 2002, accepted 21 January 2003 1. Introduction & Liòka 1996, Sinev 2001) concern occasionally collected single specimens, and no systematic in- The Republic of Buryatia is located on the southern vestigations of scythridids have been made in the and southeastern shores of Lake Baikal. Character- region. The present article is based on material istic features of the southern part of that region are collected by the author during 13.–29.VI.2002 in mountain ranges: East Sayan Mountains in the west southern Buryatia. -

Pine Nuts: a Review of Recent Sanitary Conditions and Market Development

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 17 July 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201707.0041.v1 Peer-reviewed version available at Forests 2017, 8, 367; doi:10.3390/f8100367 Article Pine nuts: a review of recent sanitary conditions and market development Hafiz Umair M. Awan 1 and Davide Pettenella 2,* 1 Department of Forest Science, University of Helsinki, Finland; [email protected], [email protected] 2 Department Land, Environment, Agriculture and Forestry – University of Padova, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +39-049-827-2741 Abstract: Pine nuts are non-wood forest products (NWFP) with constantly growing market notwithstanding a series of phytosanitary issues and related trade problems. The aim of paper is to review the literature on the relationship between phytosanitary problems and trade development. Production and trade of pine nuts in Mediterranean Europe have been negatively affected by the spreading of Sphaeropsis sapinea (a fungus) associated to an adventive insect Leptoglossus occidentalis (fungal vector), with impacts on forest management activities, production and profitability and thus in value chain organization. Reduced availability of domestic production in markets with growing demand has stimulated the import of pine nuts. China has become a leading exporter of pine nuts, but its export is affected by a symptom associated to the nuts of some pine species: the ‘pine nut syndrome’ (PNS). Most of the studies embraced during the review are associated to PNS occurrence associated to the nuts of Pinus armandii. In the literature review we highlight the need for a comprehensive and interdisciplinary approach to the analysis of the pine nuts value chain organization, where research on food properties and clinical toxicology be connected to breeding and forest management, forest pathology and entomology and trade development studies. -

Hylobius Abietis

On the cover: Stand of eastern white pine (Pinus strobus) in Ottawa National Forest, Michigan. The image was modified from a photograph taken by Joseph O’Brien, USDA Forest Service. Inset: Cone from red pine (Pinus resinosa). The image was modified from a photograph taken by Paul Wray, Iowa State University. Both photographs were provided by Forestry Images (www.forestryimages.org). Edited by: R.C. Venette Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, St. Paul, MN The authors gratefully acknowledge partial funding provided by USDA Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Plant Protection and Quarantine, Center for Plant Health Science and Technology. Contributing authors E.M. Albrecht, E.E. Davis, and A.J. Walter are with the Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. Table of Contents Introduction......................................................................................................2 ARTHROPODS: BEETLES..................................................................................4 Chlorophorus strobilicola ...............................................................................5 Dendroctonus micans ...................................................................................11 Hylobius abietis .............................................................................................22 Hylurgops palliatus........................................................................................36 Hylurgus ligniperda .......................................................................................46 -

Diversity of Pinus Sibirica Forest Types in Different Bioclimatic Sectors of Sayan Mountains

BIO Web of Conferences 16, 00045 (2019) https://doi.org/10.1051/bioconf/20191600045 Results and Prospects of Geobotanical Research in Siberia Diversity of Pinus sibirica forest types in different bioclimatic sectors of Sayan Mountains Dilshad M. Danilina*, Dina I. Nazimova, Maria E. Konovalova Sukachev Institute of Forest SB RAS, Akademgorodok, 50/28, Krasnoyarsk, 660036, Russia Abstract. The typological diversity of the three climatic facies of Siberian pine forests is considered in various bioclimatic sectors of the Prienisseysky Sayans. In each of the Sayan bioclimatic sectors, Siberian pine forests have a number of characteristic features of floristic composition and phytocenotic structure, restoration-age dynamics, productivity, and renewal process. 1 Introduction The Siberian pine forests of the Western and Eastern Sayans are currently studied typologically, thanks to the works of Russian researchers, including botanists of Siberia [1- 4]. A big step was taken at the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st centuries with the introduction of forest typological schemes to forest management, which was done by employees of academic institutes in Novosibirsk, Tomsk, Krasnoyarsk [5,6]. Databases on the biodiversity of Siberian pine forests have been created, and this allows us to study the diversity and natural relationships of Siberian pine forests in the Altai-Sayan Ecoregion at modern level [2, 7-10]. As one of the results of this work, based on the field materials of the authors and forest inventory materials, we consider the laws that govern the geography and dynamic trends in the formation of mountain dark coniferous forests after disturbances and anthropogenic interventions in the vast territory of the Prienisseysky Sayan Mountains. -

Factors Promoting Larch Dominance in Central Siberia: Fire Versus Growth Performance and Implications for Carbon Dynamics At

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Crossref Biogeosciences, 9, 1405–1421, 2012 www.biogeosciences.net/9/1405/2012/ Biogeosciences doi:10.5194/bg-9-1405-2012 © Author(s) 2012. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Factors promoting larch dominance in central Siberia: fire versus growth performance and implications for carbon dynamics at the boundary of evergreen and deciduous conifers E.-D. Schulze1, C. Wirth2, D. Mollicone1,3, N. von Lupke¨ 4, W. Ziegler1, F. Achard3, M. Mund4, A. Prokushkin5, and S. Scherbina6 1Max-Planck Institute for Biogeochemistry, P.O. Box 100164, 07701 Jena, Germany 2Institute of Biology, University of Leipzig, Johannisalle 21–23, 04103 Leipzig, Germany 3Institute of Environment and Sustainability, Joint Research Centre – TP440, 21027 Ispra, Italy 4Dept. of Ecoinformatics,Bioemetrics and Forest Growth, University of Gottingen,¨ Busgenweg¨ 4, 37077 Gottingen,¨ Germany 5V. N. Sukachev Institute of Forest, SB-RAS, Krasnoyarsk, Russia 6Centralno-Sibirsky Natural Reserve, Bor, Russia Correspondence to: E.-D. Schulze ([email protected]) Received: 3 November 2011 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 2 January 2012 Revised: 5 March 2012 – Accepted: 13 March 2012 – Published: 16 April 2012 Abstract. The relative role of fire and of climate in deter- Biomass of stems of single trees did not show signs mining canopy species composition and aboveground car- of age-related decline. Relative diameter increment was bon stocks were investigated. Measurements were made 0.41 ± 0.20 % at breast height and stem volume increased along a transect extending from the dark taiga zone of cen- linearly over time with a rate of about 0.36 t C ha−1 yr−1 in- tral Siberia, where Picea and Abies dominate the canopy, dependent of age class and species.