A Parent's Guide to Enhancing Quality of Life in Children with Cancer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Slayage, Number 16

Roz Kaveney A Sense of the Ending: Schrödinger's Angel This essay will be included in Stacey Abbott's Reading Angel: The TV Spinoff with a Soul, to be published by I. B. Tauris and appears here with the permission of the author, the editor, and the publisher. Go here to order the book from Amazon. (1) Joss Whedon has often stated that each year of Buffy the Vampire Slayer was planned to end in such a way that, were the show not renewed, the finale would act as an apt summation of the series so far. This was obviously truer of some years than others – generally speaking, the odd-numbered years were far more clearly possible endings than the even ones, offering definitive closure of a phase in Buffy’s career rather than a slingshot into another phase. Both Season Five and Season Seven were particularly planned as artistically satisfying conclusions, albeit with very different messages – Season Five arguing that Buffy’s situation can only be relieved by her heroic death, Season Seven allowing her to share, and thus entirely alleviate, slayerhood. Being the Chosen One is a fatal burden; being one of the Chosen Several Thousand is something a young woman might live with. (2) It has never been the case that endings in Angel were so clear-cut and each year culminated in a slingshot ending, an attention-grabber that kept viewers interested by allowing them to speculate on where things were going. Season One ended with the revelation that Angel might, at some stage, expect redemption and rehumanization – the Shanshu of the souled vampire – as the reward for his labours, and with the resurrection of his vampiric sire and lover, Darla, by the law firm of Wolfram & Hart and its demonic masters (‘To Shanshu in LA’, 1022). -

James Patterson by Series

HOME BOOKS COMING RELEASES COMMUNITY ABOUT JAMES ShareShare Shareon on onre pinterest_share facebook Sharingprint on twitter Services ALL BOOKS » PRE-ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY Checklist A—Z By Series Stand-Alone by Categories Comics Movies Games Apps Chronologically listed with most recent at the top within each series ALEX CROSS Cross Justice | Pre-Order Book Hope to Die | Buy Book Cross My Heart | Buy Book Alex Cross, Run | Buy Book Kill Alex Cross | Buy Book Cross Fire | Buy Book I, Alex Cross | Buy Book Cross Country | Buy Book Double Cross | Buy Book Alex Cross (Also published as Cross) | Buy Book In Stores Now Mary, Mary | Buy Book London Bridges | Buy Book The Big Bad Wolf | Buy Book Four Blind Mice | Buy Book Violets Are Blue | Buy Book Roses Are Red | Buy Book Pop Goes the Weasel | Buy Book The Murder House Cat & Mouse | Buy Book Hardcover Jack & Jill | Buy Book Kiss the Girls | Buy Book 1 of 4 Along Came a Spider | Buy Book Others (Not part of the main series) Merry Christmas, Alex Cross | Buy Book Alex Cross's Trial | Buy Book WOMEN'S MURDER CLUB 15th Affair | Pre-Order Book Truth or Die Hardcover 14th Deadly Sin | Buy Book Unlucky 13 | Buy Book 12th of Never | Buy Book See the entire checklist of books 11th Hour | Buy Book 10th Anniversary | Buy Book Coming Releases The 9th Judgment | Buy Book The 8th Confession | Buy Book 11.23.15 Cross Justice Pre-Order 7th Heaven | Buy Book The 6th Target | Buy Book 11.23.15 House of Robots: Robots G Pre-Order The 5th Horseman | Buy Book 12.14.15 I Funny TV 4th of July | Buy Book 3rd Degree | Buy Book 12.15.15 Maximum Ride: The Mang Pre-Order 2nd Chance | Buy Book 1st to Die | Buy Book 01.25.16 Private Paris 03.14.16 NYPD Red 4 MICHAEL BENNETT Alert | Buy Book 05.02.16 15th Affair Burn | Buy Book Gone | Buy Book I, Michael Bennett | Buy Book Tick Tock | Buy Book Worst Case | Buy Book Run For Your Life | Buy Book Step on a Crack | Buy Book PRIVATE Private Paris | Pre-Order Book Private Vegas | Buy Book Private L.A. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

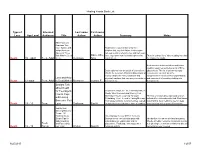

Healing Hearts Book List Type of Loss Age Level Intended Audience Title

Healing Hearts Book List Type of Intended Last name First name Loss Age Level Audience Title Author Author Summary Notes After You Lose Someone You Love: Advice and Book told in a journal format by three Insight from the children that lost their father. Entries span Diaries of Three two years with a reflection five and half years Kids Who've Been Dave, Allie, later. Age span from four and eight to nine There is a short list of other reading materials Death 10 - adult Teen, Adult There. Dennison Amy and thirteen. for children to adults. Book includes both non-fiction and fiction reading resources as well as a list of films Book explores how the death of a loved one about death. The list of advanced study affects the survivors. Practical discussions of resources is excellent as is the how to handle the many emotional and comprehensive list of service organizations Loss and How physical reactions that one may encounter in and sources of information dealing with Death 12-adult Teen, Adult to Deal With It Bernstein Joanne E. bereavement. bereavement Straight Talk about Death for Teenagers: Book has 6 chapters - The First Days After a How to Cope Death, Who Died and How; Facing Your Immediate Future; Learning To Cope; There is a section about spiritually and an with Losing Rebuilding Your Life and In Loving Memory. individual's relationship with God. Facilitators Someone You Each page contains 3-4 short entries related may find this book helpful to use for ideas Death 13 - 19 Teen Love Grollman Earl A. -

Angels Who Stepped Outside Their Houses: “American True Womanhood” and Nineteenth-Century (Trans)Nationalisms

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Doctoral Dissertations Dissertations and Theses March 2020 ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS Gayathri M. Hewagama University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2 Part of the Literature in English, North America Commons Recommended Citation Hewagama, Gayathri M., "ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS" (2020). Doctoral Dissertations. 1830. https://doi.org/10.7275/4akx-mw86 https://scholarworks.umass.edu/dissertations_2/1830 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Dissertations and Theses at ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS A Dissertation Presented By GAYATHRI MADHURANGI HEWAGAMA Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY February 2020 Department of English © Copyright by Gayathri Madhurangi Hewagama 2020 All Rights Reserved ANGELS WHO STEPPED OUTSIDE THEIR HOUSES: “AMERICAN TRUE WOMANHOOD” AND NINETEENTH-CENTURY (TRANS)NATIONALISMS A Dissertation Presented By GAYATHRI MADHURANGI HEWAGAMA Approved as to style and content by Nicholas K. Bromell, Chair Hoang G. Phan, Member Randall K. Knoper, Member Adam Dahl, Member Donna LeCourt, Acting Chair Department of English DEDICATION To my mother, who taught me my first word in English. -

Psychological Thrillers

Psychological Thrillers Alexander, Gary Blanchard, Alice 7. Persuader Blood Sacrifice Darkness Peering 8. The Enemy Andrews, Russell The Breathtaker 9. One Shot Icarus Blauner, Peter 10. The Hard Way Anscombe, Roderick The Intruder 11. Bad Luck and Trouble Paul Lucas The Last Good Day 12. Nothing to Lose 1. The Interview Room Slipping into Darkness 13. Gone Tomorrow 2. Virgin Lies Bollen, Christopher 14. 61 Hours Anthony, Sterling The Destroyers 15. Worth Dying For Cookie Cutter Bolton, S.J. 16. The Affair Archer, Jeffrey Little Black Lies 17. A Wanted Man A Prisoner of Birth Lacey Flint 18. Never Go Back Baldacci, David 1. Now You See Me 19. Personal Last Man Standing 2. Dead Scared 20. Make Me Amos Decker 3. Lost 21. Night School 1. Memory Man 4. A Dark and Twisted Tide 22. The Midnight Line 2. The Last Mile Bonansinga, Jay R. 23. Past Tense 3. The Fix Head Case 24. Blue Moon 4. The Fallen Brundage, Elizabeth No Middle Name 5. Redemption The Doctor’s Wife Clark, Mary Higgins Atlee Pine Burke, Alafair All Through the Night 1. Long Road to Mercy The Wife Before I Say Good-Bye 2. A Minute to Midnight Burke, Jan I’ll Walk Alone Sean King & Michelle Maxwell Irene Kelly I’ve Got My Eyes on You 1. Split Second 1. Goodnight, Irene Kiss the Girls and Make Them Cry 2. Hour Game 2. Sweet Dreams, Irene The Melody Lingers On 3. Simple Genius 3. Dear Irene Moonlight Becomes You 4. First Family 4. Remember Me Irene Pretend You Don’t See Her 5. -

DECLARATION of Jane Sunderland in Support of Request For

Columbia Pictures Industries Inc v. Bunnell Doc. 373 Att. 1 Exhibit 1 Twentieth Century Fox Film Corporation Motion Pictures 28 DAYS LATER 28 WEEKS LATER ALIEN 3 Alien vs. Predator ANASTASIA Anna And The King (1999) AQUAMARINE Banger Sisters, The Battle For The Planet Of The Apes Beach, The Beauty and the Geek BECAUSE OF WINN-DIXIE BEDAZZLED BEE SEASON BEHIND ENEMY LINES Bend It Like Beckham Beneath The Planet Of The Apes BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE BIG MOMMA'S HOUSE 2 BLACK KNIGHT Black Knight, The Brokedown Palace BROKEN ARROW Broken Arrow (1996) BROKEN LIZARD'S CLUB DREAD BROWN SUGAR BULWORTH CAST AWAY CATCH THAT KID CHAIN REACTION CHASING PAPI CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN CHEAPER BY THE DOZEN 2 Clearing, The CLEOPATRA COMEBACKS, THE Commando Conquest Of The Planet Of The Apes COURAGE UNDER FIRE DAREDEVIL DATE MOVIE 4 Dockets.Justia.com DAY AFTER TOMORROW, THE DECK THE HALLS Deep End, The DEVIL WEARS PRADA, THE DIE HARD DIE HARD 2 DIE HARD WITH A VENGEANCE DODGEBALL: A TRUE UNDERDOG STORY DOWN PERISCOPE DOWN WITH LOVE DRIVE ME CRAZY DRUMLINE DUDE, WHERE'S MY CAR? Edge, The EDWARD SCISSORHANDS ELEKTRA Entrapment EPIC MOVIE ERAGON Escape From The Planet Of The Apes Everyone's Hero Family Stone, The FANTASTIC FOUR FAST FOOD NATION FAT ALBERT FEVER PITCH Fight Club, The FIREHOUSE DOG First $20 Million, The FIRST DAUGHTER FLICKA Flight 93 Flight of the Phoenix, The Fly, The FROM HELL Full Monty, The Garage Days GARDEN STATE GARFIELD GARFIELD A TAIL OF TWO KITTIES GRANDMA'S BOY Great Expectations (1998) HERE ON EARTH HIDE AND SEEK HIGH CRIMES 5 HILLS HAVE -

List of Books in Popular Series

Robert Langdon series Mitch Rapp series Jack Reacher series by Dan Brown by Vince Flynn by Lee Child 1. Angels & Demons (books 15 on by Kyle Mills) 1. Killing Floor 2. The Da Vinci Code 1. American Assassin 2. Die Trying 3. The Lost Symbol 2. Kill Shot 3. Tripwire 4. Inferno 3. Transfer of Power 4. Running Blind 5. Origin 4. The Third Option 5. Echo Burning 5. Separation of Power 6. Without Fail 6. Executive Power 7. Persuader Outlander series 7. Memorial Day 8. The Enemy by Diana Gabaldon 8. Consent to Kill 9. One Shot 1. Outlander 9. Act of Treason 10. The Hard Way 2. Dragonfly in Amber 10. Protect and Defend 11. Bad Luck and Trouble 3. Voyager 11. Extreme Measures 12. Nothing to Lose 4. Drums of Autumn 12. Pursuit of Honor 13. Gone Tomorrow 5. The Fiery Cross 13. The Last Man 14. 61 Hours 6. A Breath of Snow and Ashes 14. The Survivor 15. Worth Dying For 7. An Echo in Bone 15. Order to Kill 16. The Affair 8. Written in My Own Heart's Blood 16. Enemy of the State 17. A Wanted Man 18. Never Go Back 19. Personal Fifty Shades of Grey series 20. Make Me by E.L. James A Song of Ice and Fire series 21. Night School 1. Fifty Shades of Grey by George R.R. Martin 22. The Midnight Line 2. Fifty Shades Darker 1. A Game of Thrones 3. Fifty Shades Freed 2. A Clash of Kings 4. Grey 3. A Storm of Swords 5. -

Maximum Ride: the Manga, Vol

MAXIMUM RIDE: THE MANGA, VOL. 1 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Patterson | 256 pages | 29 Sep 2015 | Little, Brown & Company | 9780759529519 | English | New York, United States MAXIMUM RIDE: THE MANGA, VOL. 1 PDF Book Shelves: beautiful-cover , disliked-a-character , trash , own-it , read-it-soooo-long-ago , too-simple. From what I remember of the actual books, this follows it to a T. Sign in for more lists. Maximum Ride and the other members of the Flock have barely recovered from their last arctic adventure, when they are confronted by the most frightening catastrophe yet. Now it's up to Max to organize a rescue, but will help come in time? View 1 comment. View Product. A young priestess joins her first adventuring party but almost immediately encounters the most unspeakable The first edition of the novel was published in January 27th , and was written by James Patterson. Of course, the story itself suffers from certain overdone tropes, especially in personalities; however, I didn't find them to be as noticeable here. But where the flock goes, erasers are sure to follow! It flew by, a light and easy read without too much thought and the most basic of content, especially as far as reading I remember when I first picked up this manga, my interest was raised by the title. Ratings and reviews Write a review. After the mutant Erasers abduct the youngest member of their group, the Bird Kids, who are the result of genetic experimentation, take off in pursuit and find themselves struggling to understand their own origins and purpose. -

North Carolina School of the Arts Bulletin 2002-2003

NORTH CAROLINA SCHOOL OF THE ARTS BULLETIN 2002-2003 Dance Design & Production Drama Filmmaking Music Visual Arts General Studies Graduate, undergraduate and secondary education for careers in the arts One of the 16 constituent institutions of the University of North Carolina Accredited by the Commission on Colleges of the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools to award the Bachelor of Fine Arts in Dance, Design & Production, Drama, and Filmmaking and the Bachelor of Music; the Arts Diploma; and the Master of Fine Arts in Design & Production and the Master of Music. The School is also accredited by the Commission on Secondary Schools to award the high school diploma with concentrations in dance, drama, music, and the visual arts. This bulletin is published biennially and provides the basic information you will need to know about the North Carolina School of the Arts. It includes admission standards and requirements, tuition and other costs, sources of financial aid, the rules and regulations which govern student life and the School’s matriculation requirements. It is your responsibility to know this information and to follow the rules and regulations as they are published in this bulletin. The School reserves the right to make changes in tuition, curriculum, rules and regulations, and in other areas as deemed necessary. The North Carolina School of the Arts is committed to equality of educational opportunity and does not discriminate against applicants, students, or employees based on race, color, national origin, religion, gender, age, disability or sexual orientation. North Carolina School of the Arts 1533 S. Main St. Winston-Salem, NC 27127-2188 336-770-3290 Fax 336-770-3370 http://www.ncarts.edu 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Academic Calendar 2002-2004 .....................................................................................Pg. -

James Patterson

HOME BOOKS COMING RELEASES COMMUNITY ABOUT JAMES ShareShare Shareon on onre pinterest_share facebook Sharingprint on twitter Services ALL BOOKS » PRE-ORDER YOUR COPY TODAY Checklist A—Z By Series Stand-Alone by Categories Comics Movies Games Apps # 1st to Die (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 2nd Chance (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 3rd Degree (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 4th of July (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book The 5th Horseman (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book The 6th Target (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 7th Heaven (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book The 8th Confession (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book The 9th Judgment (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 10th Anniversary (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book In Stores Now 11th Hour (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 12th of Never (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 14th Deadly Sin (Women's Murder Club Series) | Buy Book 15th Affair (Women's Murder Club Series) | Pre-Order Book A-E Against Medical Advice | Buy Book Alex Cross Also published as Cross (Alex Cross Series) | Buy Book Alert (Michael Bennett Series) | Buy Book The Murder Alex Cross, Run (Alex Cross Series) | Buy Book House Hardcover Alex Cross's Trial | Buy Book Along Came a Spider (Alex Cross Series) | Buy Book 1 of 5 Angel (Maximum Ride Series) | Buy Book The Angel Experiment (Maximum Ride Series) | Buy Book Armageddon (Daniel X Series) | Buy Book Beach House | Buy Book Beach Road | Buy Book The Big Bad Wolf (Alex Cross Series) | Buy Book Truth -

Parting Gifts

My Mother’s Parting Gifts PARTING GIFTS by Puja Thomson MY MOTHER'S FIRST "PARTING GIFT" came to me unrecognized and indeed unwelcome two years before she died. It was her cantankerous upset at my gadding about seeing friends throughout the 12 days I was back home in Edinburgh. "I don't know why you bothered to come, you haven't spent much time with us!" she said. Pangs of guilt, resentment welled up. Didn't she recognize the time I had spent with her? Old feelings of being controlled flashed up. The mother-daughter saga, and underneath, a truth—I was overextended and exhausted, torn in many directions, with many friends to see. I was fitting them in, a lunch here, tea or a walk there. It was true. I wasn't really with family, not in any depth. Perhaps she sensed that the sands of time were already running out in her life. "Don't come back if you're just going to use this house as a hotel for seeing friends," she fired. I had to ask myself, what did I really want? On the one hand, I was angry at being told what to do, how to live, what's right, what's wrong, all themes of my youth and upbringing. On the other hand, I sensed an incompletion and a possible step yet to be taken to bring healing to us both—before it was time for her to leave her body. I sensed a longing and a willingness to be more available to her before it was too late.