Supplementary Figure 1 a C E G B D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genome-Wide Analysis of 5-Hmc in the Peripheral Blood of Systemic Lupus Erythematosus Patients Using an Hmedip-Chip

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MOLECULAR MEDICINE 35: 1467-1479, 2015 Genome-wide analysis of 5-hmC in the peripheral blood of systemic lupus erythematosus patients using an hMeDIP-chip WEIGUO SUI1*, QIUPEI TAN1*, MING YANG1, QIANG YAN1, HUA LIN1, MINGLIN OU1, WEN XUE1, JIEJING CHEN1, TONGXIANG ZOU1, HUANYUN JING1, LI GUO1, CUIHUI CAO1, YUFENG SUN1, ZHENZHEN CUI1 and YONG DAI2 1Guangxi Key Laboratory of Metabolic Diseases Research, Central Laboratory of Guilin 181st Hospital, Guilin, Guangxi 541002; 2Clinical Medical Research Center, the Second Clinical Medical College of Jinan University (Shenzhen People's Hospital), Shenzhen, Guangdong 518020, P.R. China Received July 9, 2014; Accepted February 27, 2015 DOI: 10.3892/ijmm.2015.2149 Abstract. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a chronic, Introduction potentially fatal systemic autoimmune disease characterized by the production of autoantibodies against a wide range Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a typical systemic auto- of self-antigens. To investigate the role of the 5-hmC DNA immune disease, involving diffuse connective tissues (1) and modification with regard to the onset of SLE, we compared is characterized by immune inflammation. SLE has a complex the levels 5-hmC between SLE patients and normal controls. pathogenesis (2), involving genetic, immunologic and envi- Whole blood was obtained from patients, and genomic DNA ronmental factors. Thus, it may result in damage to multiple was extracted. Using the hMeDIP-chip analysis and valida- tissues and organs, especially the kidneys (3). SLE arises from tion by quantitative RT-PCR (RT-qPCR), we identified the a combination of heritable and environmental influences. differentially hydroxymethylated regions that are associated Epigenetics, the study of changes in gene expression with SLE. -

Small Cell Ovarian Carcinoma: Genomic Stability and Responsiveness to Therapeutics

Gamwell et al. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 2013, 8:33 http://www.ojrd.com/content/8/1/33 RESEARCH Open Access Small cell ovarian carcinoma: genomic stability and responsiveness to therapeutics Lisa F Gamwell1,2, Karen Gambaro3, Maria Merziotis2, Colleen Crane2, Suzanna L Arcand4, Valerie Bourada1,2, Christopher Davis2, Jeremy A Squire6, David G Huntsman7,8, Patricia N Tonin3,4,5 and Barbara C Vanderhyden1,2* Abstract Background: The biology of small cell ovarian carcinoma of the hypercalcemic type (SCCOHT), which is a rare and aggressive form of ovarian cancer, is poorly understood. Tumourigenicity, in vitro growth characteristics, genetic and genomic anomalies, and sensitivity to standard and novel chemotherapeutic treatments were investigated in the unique SCCOHT cell line, BIN-67, to provide further insight in the biology of this rare type of ovarian cancer. Method: The tumourigenic potential of BIN-67 cells was determined and the tumours formed in a xenograft model was compared to human SCCOHT. DNA sequencing, spectral karyotyping and high density SNP array analysis was performed. The sensitivity of the BIN-67 cells to standard chemotherapeutic agents and to vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and the JX-594 vaccinia virus was tested. Results: BIN-67 cells were capable of forming spheroids in hanging drop cultures. When xenografted into immunodeficient mice, BIN-67 cells developed into tumours that reflected the hypercalcemia and histology of human SCCOHT, notably intense expression of WT-1 and vimentin, and lack of expression of inhibin. Somatic mutations in TP53 and the most common activating mutations in KRAS and BRAF were not found in BIN-67 cells by DNA sequencing. -

An Animal Model with a Cardiomyocyte-Specific Deletion of Estrogen Receptor Alpha: Functional, Metabolic, and Differential Netwo

Washington University School of Medicine Digital Commons@Becker Open Access Publications 2014 An animal model with a cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of estrogen receptor alpha: Functional, metabolic, and differential network analysis Sriram Devanathan Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Timothy Whitehead Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis George G. Schweitzer Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Nicole Fettig Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis Attila Kovacs Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs Recommended Citation Devanathan, Sriram; Whitehead, Timothy; Schweitzer, George G.; Fettig, Nicole; Kovacs, Attila; Korach, Kenneth S.; Finck, Brian N.; and Shoghi, Kooresh I., ,"An animal model with a cardiomyocyte-specific deletion of estrogen receptor alpha: Functional, metabolic, and differential network analysis." PLoS One.9,7. e101900. (2014). https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/3326 This Open Access Publication is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons@Becker. It has been accepted for inclusion in Open Access Publications by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Becker. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Sriram Devanathan, Timothy Whitehead, George G. Schweitzer, Nicole Fettig, Attila Kovacs, Kenneth S. Korach, Brian N. Finck, and Kooresh I. Shoghi This open access publication is available at Digital Commons@Becker: https://digitalcommons.wustl.edu/open_access_pubs/3326 An Animal Model with a Cardiomyocyte-Specific Deletion of Estrogen Receptor Alpha: Functional, Metabolic, and Differential Network Analysis Sriram Devanathan1, Timothy Whitehead1, George G. Schweitzer2, Nicole Fettig1, Attila Kovacs3, Kenneth S. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

1 Metabolic Dysfunction Is Restricted to the Sciatic Nerve in Experimental

Page 1 of 255 Diabetes Metabolic dysfunction is restricted to the sciatic nerve in experimental diabetic neuropathy Oliver J. Freeman1,2, Richard D. Unwin2,3, Andrew W. Dowsey2,3, Paul Begley2,3, Sumia Ali1, Katherine A. Hollywood2,3, Nitin Rustogi2,3, Rasmus S. Petersen1, Warwick B. Dunn2,3†, Garth J.S. Cooper2,3,4,5* & Natalie J. Gardiner1* 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 2 Centre for Advanced Discovery and Experimental Therapeutics (CADET), Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK 3 Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes, Institute of Human Development, Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand 5 Department of Pharmacology, Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford, UK † Present address: School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, UK *Joint corresponding authors: Natalie J. Gardiner and Garth J.S. Cooper Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Address: University of Manchester, AV Hill Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom Telephone: +44 161 275 5768; +44 161 701 0240 Word count: 4,490 Number of tables: 1, Number of figures: 6 Running title: Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online October 15, 2015 Diabetes Page 2 of 255 Abstract High glucose levels in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy (DN). However our understanding of the molecular mechanisms which cause the marked distal pathology is incomplete. Here we performed a comprehensive, system-wide analysis of the PNS of a rodent model of DN. -

Supplementary Materials

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

) (51) International Patent Classification: Columbia V5G 1G3

) ( (51) International Patent Classification: Columbia V5G 1G3 (CA). PANDEY, Nihar R.; 10209 A 61K 31/4525 (2006.01) C07C 39/23 (2006.01) 128A St, Surrey, British Columbia V3T 3E7 (CA). A61K 31/05 (2006.01) C07D 405/06 (2006.01) (74) Agent: ZIESCHE, Sonia et al.; Gowling WLG (Canada) A61P25/22 (2006.01) LLP, 2300 - 550 Burrard Street, Vancouver, British Colum¬ (21) International Application Number: bia V6C 2B5 (CA). PCT/CA2020/050165 (81) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every (22) International Filing Date: kind of national protection av ailable) . AE, AG, AL, AM, 07 February 2020 (07.02.2020) AO, AT, AU, AZ, BA, BB, BG, BH, BN, BR, BW, BY, BZ, CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, (25) Filing Language: English DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, (26) Publication Language: English HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (30) Priority Data: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, 16/270,389 07 February 2019 (07.02.2019) US OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (63) Related by continuation (CON) or continuation-in-part SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, TR, (CIP) to earlier application: TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, WS, ZA, ZM, ZW. US 16/270,389 (CON) (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every Filed on 07 Februaiy 2019 (07.02.2019) kind of regional protection available) . -

Review Article PTEN Gene: a Model for Genetic Diseases in Dermatology

The Scientific World Journal Volume 2012, Article ID 252457, 8 pages The cientificWorldJOURNAL doi:10.1100/2012/252457 Review Article PTEN Gene: A Model for Genetic Diseases in Dermatology Corrado Romano1 and Carmelo Schepis2 1 Unit of Pediatrics and Medical Genetics, I.R.C.C.S. Associazione Oasi Maria Santissima, 94018 Troina, Italy 2 Unit of Dermatology, I.R.C.C.S. Associazione Oasi Maria Santissima, 94018 Troina, Italy Correspondence should be addressed to Carmelo Schepis, [email protected] Received 19 October 2011; Accepted 4 January 2012 Academic Editors: G. Vecchio and H. Zitzelsberger Copyright © 2012 C. Romano and C. Schepis. This is an open access article distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. PTEN gene is considered one of the most mutated tumor suppressor genes in human cancer, and it’s likely to become the first one in the near future. Since 1997, its involvement in tumor suppression has smoothly increased, up to the current importance. Germline mutations of PTEN cause the PTEN hamartoma tumor syndrome (PHTS), which include the past-called Cowden, Bannayan- Riley-Ruvalcaba, Proteus, Proteus-like, and Lhermitte-Duclos syndromes. Somatic mutations of PTEN have been observed in glioblastoma, prostate cancer, and brest cancer cell lines, quoting only the first tissues where the involvement has been proven. The negative regulation of cell interactions with the extracellular matrix could be the way PTEN phosphatase acts as a tumor suppressor. PTEN gene plays an essential role in human development. A recent model sees PTEN function as a stepwise gradation, which can be impaired not only by heterozygous mutations and homozygous losses, but also by other molecular mechanisms, such as transcriptional regression, epigenetic silencing, regulation by microRNAs, posttranslational modification, and aberrant localization. -

WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT

(12) INTERNATIONAL APPLICATION PUBLISHED UNDER THE PATENT COOPERATION TREATY (PCT) (19) World Intellectual Property Organization I International Bureau (10) International Publication Number (43) International Publication Date WO 2019/079361 Al 25 April 2019 (25.04.2019) W 1P O PCT (51) International Patent Classification: CA, CH, CL, CN, CO, CR, CU, CZ, DE, DJ, DK, DM, DO, C12Q 1/68 (2018.01) A61P 31/18 (2006.01) DZ, EC, EE, EG, ES, FI, GB, GD, GE, GH, GM, GT, HN, C12Q 1/70 (2006.01) HR, HU, ID, IL, IN, IR, IS, JO, JP, KE, KG, KH, KN, KP, KR, KW, KZ, LA, LC, LK, LR, LS, LU, LY, MA, MD, ME, (21) International Application Number: MG, MK, MN, MW, MX, MY, MZ, NA, NG, NI, NO, NZ, PCT/US2018/056167 OM, PA, PE, PG, PH, PL, PT, QA, RO, RS, RU, RW, SA, (22) International Filing Date: SC, SD, SE, SG, SK, SL, SM, ST, SV, SY, TH, TJ, TM, TN, 16 October 2018 (16. 10.2018) TR, TT, TZ, UA, UG, US, UZ, VC, VN, ZA, ZM, ZW. (25) Filing Language: English (84) Designated States (unless otherwise indicated, for every kind of regional protection available): ARIPO (BW, GH, (26) Publication Language: English GM, KE, LR, LS, MW, MZ, NA, RW, SD, SL, ST, SZ, TZ, (30) Priority Data: UG, ZM, ZW), Eurasian (AM, AZ, BY, KG, KZ, RU, TJ, 62/573,025 16 October 2017 (16. 10.2017) US TM), European (AL, AT, BE, BG, CH, CY, CZ, DE, DK, EE, ES, FI, FR, GB, GR, HR, HU, ΓΕ , IS, IT, LT, LU, LV, (71) Applicant: MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF MC, MK, MT, NL, NO, PL, PT, RO, RS, SE, SI, SK, SM, TECHNOLOGY [US/US]; 77 Massachusetts Avenue, TR), OAPI (BF, BJ, CF, CG, CI, CM, GA, GN, GQ, GW, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 (US). -

TITLE PAGE Oxidative Stress and Response to Thymidylate Synthase

Downloaded from molpharm.aspetjournals.org at ASPET Journals on October 2, 2021 -Targeted -Targeted 1 , University of of , University SC K.W.B., South Columbia, (U.O., Carolina, This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. The final version may differ from this version. This article has not been copyedited and formatted. -

Supplementary File 2A Revised

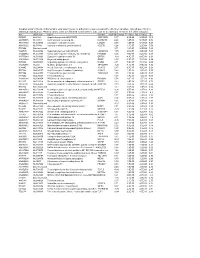

Supplementary file 2A. Differentially expressed genes in aldosteronomas compared to all other samples, ranked according to statistical significance. Missing values were not allowed in aldosteronomas, but to a maximum of five in the other samples. Acc UGCluster Name Symbol log Fold Change P - Value Adj. P-Value B R99527 Hs.8162 Hypothetical protein MGC39372 MGC39372 2,17 6,3E-09 5,1E-05 10,2 AA398335 Hs.10414 Kelch domain containing 8A KLHDC8A 2,26 1,2E-08 5,1E-05 9,56 AA441933 Hs.519075 Leiomodin 1 (smooth muscle) LMOD1 2,33 1,3E-08 5,1E-05 9,54 AA630120 Hs.78781 Vascular endothelial growth factor B VEGFB 1,24 1,1E-07 2,9E-04 7,59 R07846 Data not found 3,71 1,2E-07 2,9E-04 7,49 W92795 Hs.434386 Hypothetical protein LOC201229 LOC201229 1,55 2,0E-07 4,0E-04 7,03 AA454564 Hs.323396 Family with sequence similarity 54, member B FAM54B 1,25 3,0E-07 5,2E-04 6,65 AA775249 Hs.513633 G protein-coupled receptor 56 GPR56 -1,63 4,3E-07 6,4E-04 6,33 AA012822 Hs.713814 Oxysterol bining protein OSBP 1,35 5,3E-07 7,1E-04 6,14 R45592 Hs.655271 Regulating synaptic membrane exocytosis 2 RIMS2 2,51 5,9E-07 7,1E-04 6,04 AA282936 Hs.240 M-phase phosphoprotein 1 MPHOSPH -1,40 8,1E-07 8,9E-04 5,74 N34945 Hs.234898 Acetyl-Coenzyme A carboxylase beta ACACB 0,87 9,7E-07 9,8E-04 5,58 R07322 Hs.464137 Acyl-Coenzyme A oxidase 1, palmitoyl ACOX1 0,82 1,3E-06 1,2E-03 5,35 R77144 Hs.488835 Transmembrane protein 120A TMEM120A 1,55 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,07 H68542 Hs.420009 Transcribed locus 1,07 1,7E-06 1,4E-03 5,06 AA410184 Hs.696454 PBX/knotted 1 homeobox 2 PKNOX2 1,78 2,0E-06 -

NATURAL KILLER CELLS, HYPOXIA, and EPIGENETIC REGULATION of HEMOCHORIAL PLACENTATION by Damayanti Chakraborty Submitted to the G

NATURAL KILLER CELLS, HYPOXIA, AND EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF HEMOCHORIAL PLACENTATION BY Damayanti Chakraborty Submitted to the graduate degree program in Pathology and Laboratory Medicine and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chair: Michael J. Soares, Ph.D. ________________________________ Jay Vivian, Ph.D. ________________________________ Patrick Fields, Ph.D. ________________________________ Soumen Paul, Ph.D. ________________________________ Michael Wolfe, Ph.D. ________________________________ Adam J. Krieg, Ph.D. Date Defended: 04/01/2013 The Dissertation Committee for Damayanti Chakraborty certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: NATURAL KILLER CELLS, HYPOXIA, AND EPIGENETIC REGULATION OF HEMOCHORIAL PLACENTATION ________________________________ Chair: Michael J. Soares, Ph.D. Date approved: 04/01/2013 ii ABSTRACT During the establishment of pregnancy, uterine stromal cells differentiate into decidual cells and recruit natural killer (NK) cells. These NK cells are characterized by low cytotoxicity and distinct cytokine production. In rodent as well as in human pregnancy, the uterine NK cells peak in number around mid-gestation after which they decline. NK cells associate with uterine spiral arteries and are implicated in pregnancy associated vascular remodeling processes and potentially in modulating trophoblast invasion. Failure of trophoblast invasion and vascular remodeling has been shown to be associated with pathological conditions like preeclampsia syndrome, hypertension in mother and/or fetal growth restriction. We hypothesize that NK cells fundamentally contribute to the organization of the placentation site. In order to study the in vivo role of NK cells during pregnancy, gestation stage- specific NK cell depletion was performed in rats using anti asialo GM1 antibodies.