Mn^Ttx of ^Ijtloslopbp in HISTORY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

Diasporic Fashion Space: Women's Experiences of 'South Asian'

Diasporic fashion space: women’s experiences of ‘South Asian’ dress aesthetics in London. Shivani Pandey Derrington Royal Holloway College PhD Geography 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Shivani Pandey Derrington, hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Signed:____________________ Date:______________________ 2 Abstract This thesis responds to the emergence of a ‘diasporic fashion space’ in London, examining its implications for women of South Asian descent and their lived experiences of dress. It draws upon in-depth qualitative research in which women provided testimony about their dress biographies, wardrobe collections and aesthetic agency. The aim is to complement, and advance, past research that considered the production and marketing of ‘South Asian’ fashions and textiles in Britain (e.g. Bhachu 2003, Dwyer & Jackson 2003) through a more sustained analysis of the consumption and use of styles and materials. The research is situated in relation to both specific bodies of scholarship – such as that on contemporary British Asian fashion cultures – and wider currents of thought – in particular on diasporic geographies and geographies of fashion. The approach taken draws especially from work within fashion studies that has sought to recognise lived experiences of dress. The thesis develops its argument through four complementary perspectives on the testimonies constructed in the empirical research. First, it considers the role of dress in inhabiting what is termed ‘British Asian fashion space’ and ideas of British Asian identity. Second, it then examines how dress functions as a technology of diasporic selfhood, focusing on the practice of dress choices both in everyday life and in significant ceremonies such as weddings. -

Prophets of the Quran: an Introduction (Part 1 of 2)

Prophets of the Quran: An Introduction (part 1 of 2) Description: Belief in the prophets of God is a central part of Muslim faith. Part 1 will introduce all the prophets before Prophet Muhammad, may the mercy and blessings of God be upon him, mentioned in the Muslim scripture from Adam to Abraham and his two sons. By Imam Mufti (© 2013 IslamReligion.com) Published on 22 Apr 2013 - Last modified on 25 Jun 2019 Category: Articles >Beliefs of Islam > Stories of the Prophets The Quran mentions twenty five prophets, most of whom are mentioned in the Bible as well. Who were these prophets? Where did they live? Who were they sent to? What are their names in the Quran and the Bible? And what are some of the miracles they performed? We will answer these simple questions. Before we begin, we must understand two matters: a. In Arabic two different words are used, Nabi and Rasool. A Nabi is a prophet and a Rasool is a messenger or an apostle. The two words are close in meaning for our purpose. b. There are four men mentioned in the Quran about whom Muslim scholars are uncertain whether they were prophets or not: Dhul-Qarnain (18:83), Luqman (Chapter 31), Uzair (9:30), and Tubba (44:37, 50:14). 1. Aadam or Adam is the first prophet in Islam. He is also the first human being according to traditional Islamic belief. Adam is mentioned in 25 verses and 25 times in the Quran. God created Adam with His hands and created his wife, Hawwa or Eve from Adam’s rib. -

Brahmanical Patriarchy and Voices from Below: Ambedkar's Characterization of Women's Emancipation

Open Political Science, 2020; 3: 175–182 Research Article Harsha Senanayake*, Samarth Trigunayat Brahmanical Patriarchy and Voices from Below: Ambedkar‘s Characterization of Women’s Emancipation https://doi.org/10.1515/openps-2020-0014 received May 8, 2020; accepted June 2, 2020. Abstract: Western feminism created a revolution on the international stage urging the world to look at things through the perspective of women who were historically suppressed because of their gender, yet in many instances, it failed to address the issue of women in the Indian subcontinent because of the existence of social hierarchies that are alien concepts to the western world. As a result, the impact of western feminist thinkers was limited to only the elites in the Indian subcontinent. The idea of social hierarchy is infamously unique to the South Asian context and hence, in the view of the authors, this evil has to be fought through homegrown approaches which have to address these double disadvantages that women suffer in this part of the world. While many have tried to characterize Ambedkar’s political and social philosophy into one of the ideological labels, his philosophy was essentially ‘a persistent attempt to think things through’. It becomes important here to understand what made Ambedkar different from others; what was his social condition and his status in a hierarchal Hindu Society. As a matter of his epistemology, his research and contribution did not merely stem from any particular compartmentalized consideration of politics or society, rather it encompassed the contemporary socio-political reality taking into consideration other intersectionalities like gender and caste. -

Islam Today: a Muslim Quaker's View

Quaker Universalist Group ISLAM TODAY: A MUSLIM QUAKER’S VIEW _______________________________________ Christopher Bagley QUG Pamphlet No. 34 £3.00 The Quaker Universalist Group The Quaker Universalist Group (QUG) is based on the understanding that spiritual awareness is accessible to everyone of any religion or none, and that no one person and no one faith can claim to have a final revelation or monopoly of truth. We acknowledge that such awareness may be expressed in many different ways. We delight in this diversity and warmly welcome both Quakers and non-Quakers to join us. The publishing arm of QUG is QUG Publishing. Contact details of QUG are available at www.qug.org.uk QUG Pamphlet No. 34 Islam Today: A Muslim Quaker’s View First published in 2015 by QUG Publishing ISBN: 978-0-948232-66-4 Copyright © Christopher Bagley, 2015 The moral rights of the author are asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. Printed by MP Printers (Thame) Ltd. Each Quaker Universalist Pamphlet expresses the views of its author, which are not necessarily representative of the Quaker Universalist Group as a whole. About the author Christopher served in the Royal Navy until, becoming a Christian pacifist, he refused to obey orders and was imprisoned for 12 months. After a period as a journalist (writing for Tribune, the Daily Worker, and Peace News) he studied psychiatric nursing at the Quaker Hospital, The Retreat, York, later becoming a Member of the Religious Society of Friends. After university study in mental health, psychology and social work he became a research fellow at The National Neurological Hospital, and then a researcher at The Maudsley Psychiatric Hospital, both in London. -

Transcendence of God

TRANSCENDENCE OF GOD A COMPARATIVE STUDY OF THE OLD TESTAMENT AND THE QUR’AN BY STEPHEN MYONGSU KIM A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE PHILOSOPHIAE DOCTOR (PhD) IN BIBLICAL AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES IN THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AT THE UNIVERSITY OF PRETORIA SUPERVISOR: PROF. DJ HUMAN CO-SUPERVISOR: PROF. PGJ MEIRING JUNE 2009 © University of Pretoria DEDICATION To my love, Miae our children Yein, Stephen, and David and the Peacemakers around the world. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First, I thank God for the opportunity and privilege to study the subject of divinity. Without acknowledging God’s grace, this study would be futile. I would like to thank my family for their outstanding tolerance of my late studies which takes away our family time. Without their support and kind endurance, I could not have completed this prolonged task. I am grateful to the staffs of University of Pretoria who have provided all the essential process of official matter. Without their kind help, my studies would have been difficult. Many thanks go to my fellow teachers in the Nairobi International School of Theology. I thank David and Sarah O’Brien for their painstaking proofreading of my thesis. Furthermore, I appreciate Dr Wayne Johnson and Dr Paul Mumo for their suggestions in my early stage of thesis writing. I also thank my students with whom I discussed and developed many insights of God’s relationship with mankind during the Hebrew Exegesis lectures. I also remember my former teachers from Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary, especially from the OT Department who have shaped my academic stand and inspired to pursue the subject of this thesis. -

India's Agendas on Women's Education

University of St. Thomas, Minnesota UST Research Online Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership School of Education 8-2016 The olitP icized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education Sabeena Mathayas University of St. Thomas, Minnesota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Mathayas, Sabeena, "The oP liticized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education" (2016). Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership. 81. https://ir.stthomas.edu/caps_ed_lead_docdiss/81 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Education at UST Research Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Education Doctoral Dissertations in Leadership by an authorized administrator of UST Research Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE COLLEGE OF EDUCATION, LEADERSHIP, AND COUNSELING OF THE UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS by Sabeena Mathayas IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Minneapolis, Minnesota August 2016 UNIVERSITY OF ST. THOMAS The Politicized Indian Woman: India’s Agendas on Women’s Education We certify that we have read this dissertation and approved it as adequate in scope and quality. We have found that it is complete and satisfactory in all respects, and that any and all revisions required by the final examining committee have been made. Dissertation Committee i The word ‘invasion’ worries the nation. The 106-year-old freedom fighter Gopikrishna-babu says, Eh, is the English coming to take India again by invading it, eh? – Now from the entire country, Indian intellectuals not knowing a single Indian language meet in a closed seminar in the capital city and make the following wise decision known. -

Islam 2 Markers on the Exam

NAME: DATE: 06/02/2019 UNIT 2: Islam 2 markers on the exam. Akhirah-The Muslim term for the belief in the final Judgement and life after death. Al-Qadr- The Muslim term for 'predestination' which means Muslims believe God has set out the destiny of all things. Burkha- A long, loose-fitting garment which covers the whole body from head to feet. It is worn in public by some women, and is compulsory for women in some Islamic countries. Hijab- Often used to describe the headscarf, veil or modest dress worn by many Muslim women, who are required to cover everything except face and hands in the sight of anyone other than immediate family. Id-ul-Fitr/Eid-Ul-Fitr- Celebration of breaking the fast on the day after Ramadan ends. Isa - Isa is the 24th and penultimate prophet of Islam. In Christianity he is known as Jesus. Muslims believe Isa to be a messenger of God, and in no way divine. Isa is believed to have had a miraculous, fatherless birth. He was a healer of the sick and foretold the coming of the final prophet, Muhammad. Lesser jihad- The word jihad means 'to strive. Lesser jihad is a physical struggle or 'holy war'in defence of Islam. Mecca/Makkah- Islam's holiest city, located in Saudi Arabia. Mecca is the birthplace of the Prophet Muhammad and the place where Islam originated. Mecca is the site of the Ka'ba, Islam's most sacred shrine, and is the destination of the annual Hajj pilgrimage. Muslims pray and worship facing towards Mecca, wherever they may be in the world. -

The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I*

The Politicization of the Peasantry in a North Indian State: I* Paul R. Brass** During the past three decades, the dominant party in the north Indian state of Uttar Pradesh (U. P.), the Indian National Congress, has undergone a secular decline in its support in state legislative assembly elections. The principal factor in its decline has been its inability to establish a stable basis of support among the midle peasantry, particularly among the so-called 'backward castes', with landholdings ranging from 2.5 to 30 acres. Disaffected from the Congress since the 1950s, these middle proprietary castes, who together form the leading social force in the state, turned in large numbers to the BKD, the agrarian party of Chaudhuri Charan Singh, in its first appearance in U. P. elections in 1969. They also provided the central core of support for the Janata party in its landslide victory in the 1977 state assembly elections. The politicization of the middle peasantry in this vast north Indian province is no transient phenomenon, but rather constitutes a persistent factor with which all political parties and all governments in U. P. must contend. I Introduction This articlet focuses on the state of Uttar Pradesh (U. P.), the largest state in India, with a population of over 90 million, a land area of 113,000 square miles, and a considerable diversity in political patterns, social structure, and agricul- tural ecology. My purpose in writing this article is to demonstrate how a program of modest land reform, designed to establish a system of peasant proprietorship and reenforced by the introduction of the technology of the 'green revolution', has, in the context of a political system based on party-electoral competition, enhanced the power of the middle and rich peasants. -

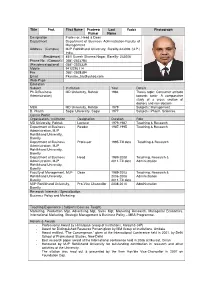

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Kumar Last Name Yadav Photograph

Title Prof. First Name Pradeep Last Yadav Photograph Kumar Name Designation Professor, Head & Dean Department Department of Business Administration-Faculty of Management Address (Campus) MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly-243006 (U.P.) India. (Residence) 45/II Suresh Sharma Nagar, Bareilly- 243006 Phone No (Campus) 0581 -2523784 (Residence)optional 0581-2525339 Mobile 9412293114 Fax 0581 -2528384 Email [email protected] Web-Page Education Subject Institution Year Details Ph.D(Business MD University, Rohtak 1984 Thesis topic: Consumer attitude Administration) towards tonic- A comparative study of a cross section of doctors and non-doctors MBA MD University, Rohtak 1979 Subjects: Management B. Pharm Sagar University, Sagar 1977 Subjects: Pharm. Sciences Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration Role MD University, Rohtak Lecturer 1979-1987 Teaching & Research Department of Business Reader 1987-1995 Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Professor 1995-Till date Teaching & Research Administration, MJP Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Department of Business Head 1989-2008 Teaching, Research & Administration, MJP 2011-Till date Administration Rohilkhand University, Bareilly Faculty of Management, MJP Dean 1989-2003 Teaching, Research & Rohilkhand University, 2006-2008 Administration Bareilly 2011-Till date MJP Rohilkhand University, Pro-Vice Chancellor 2008-2010 Administration Bareilly Research Interests / Specialization Business Policy and Marketing Teaching -

How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 11-17-2017 2:00 PM Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World Shazia Sadaf The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Joint Supervisor Julia Emberley The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in English A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Shazia Sadaf 2017 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Literature in English, Anglophone outside British Isles and North America Commons Recommended Citation Sadaf, Shazia, "Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World" (2017). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 5055. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/5055 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Terrorism, Islamization, and Human Rights: How Post 9/11 Pakistani English Literature Speaks to the World Abstract The start of the twenty-first century has witnessed a simultaneous rise of three areas of scholarly interest: 9/11 literature, human rights discourse, and War on Terror studies. The resulting intersections between literature and human rights, foregrounded by an overarching narrative of terror, have led to a new area of interdisciplinary enquiry broadly classed under human rights literature, at the point of the convergence of which lies the idea of human empathy. -

1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 2604124 30/09/2013 Trading As ;BINOD TEXTILES Address for Service In

Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 PUJA 2604124 30/09/2013 Mr Binod Kumar Todi MRS. SUDHA TODI MR. VIJAY KUMAR TODI MRS. SAVITA TODI trading as ;BINOD TEXTILES 6,RAGHUNANDAN LANE,KOLKATA 700006,WEST BENGAL Manufacturer, Merchant, and Trader. Address for service in India/Attorney address: IPR HOUSE.COM 89/269/270, BANGUR PARK, PARK TOWER, 4TH FLOOR, ROOM NO. 401, RISHRA - 712248, HOOGHLY, WEST BENGAL Used Since :31/12/1980 To be associated with: 419649 KOLKATA "Hosiery Goods, Undergarments, Vests, Briefs, Panties" 3648 Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 3043675 29/08/2015 BRAINBEES SOLUTIONS PRIVATE LIMITED. Rajashree Business Park, Plot No 114, Survey No 338, Tadiwala Road, Nr. Sohrab Hall, Pune-411001, Maharashtra, India MERCHANTS & TRADERS COMPANY INCORPORATED UNDER THE COMPANIES ACT, 1956 Address for service in India/Attorney address: LEGATARIAN IPR CONSULTANTS LLP 304, A-Wing, Pranavshree, Riddhi Siddhi Paradise, Near Manas Society, Dhayari-411041, Pune, Maharashtra, India Used Since :20/12/2014 MUMBAI ALL KINDS OF CLOTHING , FOOTWEAR AND HEADGEAR FOR BABIES. 3649 Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 CADRE 3074790 08/10/2015 VIKAS TANK trading as ;VIKAS TANK HOUSE NO- 2785, KHAZANE WALON KA RASTA, DARJIYON KA CHOUHARA, JAIPUR, RAJASTHAN M/S VIKAS TANK Address for service in India/Attorney address: MARK R SERVICES C-365 NIRMAN NAGAR KINGS ROAD JAIPUR RAJASTHAN Used Since :01/09/2015 AHMEDABAD CLOTHINGS FOR MEN, WOMEN AND KIDS, HEAD GEARS AND SHOES INCLUDING IN CLASS 25 3650 Trade Marks Journal No: 1942 , 24/02/2020 Class 25 3085949 27/10/2015 SHRI RAMZAN ALI B.