33422717.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download Map (PDF | 4.45

! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Overview - PUNJAB ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! K.P. ! ! ! ! ! ! Murree ! Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Hasan Abdal Tehsil ! Attock Tehsil ! Kotli Sattian Tehsil ! Taxila Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! Attock ! ! ! ! Jand Tehsil ! Kahuta ! Fateh Jang Tehsil Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi Tehsil ! ! ! Rawalpindi ! ! Pindi Gheb Tehsil ! J A M M U A N D K A S H M I R ! ! ! ! Gujar Khan Tehsil ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Sohawa ! Tehsil ! ! ! A F G H A N I S T A N Chakwal Chakwal ! ! ! Tehsil Sarai Alamgir Tehsil ! ! Tala Gang Tehsil Jhelum Tehsil ! Isakhel Tehsil ! Jhelum ! ! ! Choa Saidan Shah Tehsil Kharian Tehsil Gujrat Mianwali Tehsil Mianwali Gujrat Tehsil Pind Dadan Khan Tehsil Sialkot Tehsil Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Malakwal Tehsil Phalia Mandi Bahauddin Tehsil Sialkot Daska Tehsil Khushab Piplan Tehsil Tehsil Wazirabad Tehsil Pasrur Tehsil Narowal Shakargarh Tehsil Shahpur Tehsil Khushab Gujranwala Bhalwal Hafizabad Tehsil Gujranwala Tehsil Tehsil Narowal Tehsil Sargodha Kamoke Tehsil Kalur Kot Tehsil Sargodha Tehsil Hafizabad Nowshera Virkan Tehsil Pindi Bhattian Tehsil Noorpur Sahiwal Tehsil Tehsil Darya Khan Tehsil Sillanwali Tehsil Ferozewala Tehsil Safdarabad Tehsil Sheikhupura Tehsil Chiniot -

Moving Around Skills Activity Sheets (PDF 5.19

USINGMOVING Holding head up: HANDAROUND SKILLS M1A SKILLS Turning head to the side To develop muscles on both sides of the neck. TOYS & ATTENTION & ACTIVITIES CONCENTRATION › Mobiles. › Use a noisy/brightly › Pictures/posters. coloured toy to attract your child’s attention to › Bright squeaky or either side. musical toys. › Your own face; act in front of a mirror so that your child can see himself and your face. › Alternate the position of toys/mobiles in area of cot/play area. › Talk to your child from both sides and encourage your child to turn their head to see you. SONGS & ACTIONS › Change the position that your child sleeps and plays in, e.g., move the cot to a different side of the room. › Favourite music/song. › When carrying your child try to spend some time using your left side and some › Nursery rhymes. time on your right side. › When your child is lying on their back and looking at you, slowly move your head from one side to the other and encourage your child to follow your movements. › Sit in front of mirror and hold your child facing mirror. Slowly turn his body; he will want to maintain eye contact with you in the mirror. MOVING Holding head up: AROUND M1A SKILLS Turning head to the side To develop muscles on both sides of the neck. BATHING DRESSING MEALTIMES PLAYING WAKING OUTINGS › Try to alternate the › When dressing/ › When breast/ › Position yourself › Have interesting › If you have toys/ direction that the changing your bottle feeding, and your child’s items, e.g., mobiles mobiles in the car, bath is facing, e.g., child, encourage alternate sides and favourite toys positioned on both try to vary their so that the window him to look to one your position in on either side of side of the bed for position, e.g., one is on the left side side by dangling the room to create their body and your child to look week on the left one time and on something bright a variety of things encourage them to at when he awakes. -

Geospatial Analysis of Indus River Meandering and Flow Pattern from Chachran to Guddu Barrage, Pakistan Vol 9 (2), December 2018

Geospatial Analysis of Indus River Meandering and Flow Pattern from Chachran to Guddu Barrage, Pakistan Vol 9 (2), December 2018 Open Access ORIGINAL ARTICLE Full Length Ar t icle Geospatial Analysis of Indus River Meandering and Flow Pattern from Chachran to Guddu Barrage, Pakistan Danish Raza* and Aqeel Ahmed Kidwai Department of Meteorology-COMSATS University Islamabad, Islamabad, Pakistan ABS TRACT Natural and anthropogenic influence affects directly ecologic equilibrium and hydro morphologic symmetry of riverine surroundings. The current research intends to study the hydro morphologic features (meanders, shape, and size) of Indus River, Pakistan by using remote sensing (RS) and geographical information science (GIS) techniques to calculate the temporal changes. Landsat satellite imagery was used for qualitative and analytical study. Satellite imagery was acquired from Landsat Thematic Mapper (TM), Enhanced Thematic Mapper Plus (ETM+) and Operational Land Imager (OLI). Temporal satellite imagery of study area was used to identify the variations of river morphology for the years 1988,1995,2002,2009 and 2017. Research was based upon the spatial and temporal change of river pattern with respect to meandering and flow pattern observations for 30 years’ temporal data with almost 7 years’ interval. Image preprocessing was applied on the imagery of the study area for the better visualization and identification of variations among the objects. Object-based image analysis technique was performed for better results of a feature on the earth surface. Model builder (Arc GIS) was used for calculation of temporal variation of the river. In observation many natural factor involves for pattern changes such as; floods and rain fall. -

Petition CP 15-2: Petition Requesting Ban on Supplemental Mattresses for Play Yards with Non-Rigid Sides

UNITED STATES CONSUMER PRODUCT SAFETY COMMISSION 4330 EAST WEST HIGHWAY BETHESDA, MD 20814 DATE: BALLOT VOTE SHEET TO: The Commission Todd A. Stevenson, Secretary THROUGH: Mary T. Boyle, General Counsel Patricia H. Adkins, Executive Director FROM: Patricia M. Pollitzer, Assistant General Counsel Mary A. House, Attorney, OGC SUBJECT: Petition CP 15-2: Petition Requesting Ban on Supplemental Mattresses for Play Yards with Non-Rigid Sides BALLOT VOTE DUE ____________________ CPSC staff is forwarding a briefing package to the Commission regarding a petition requesting a ban on supplemental mattresses for play yards with non-rigid sides, which are currently marketed to be used with non-full-size cribs, play yards, portable cribs, and play pens (petition). The petition was submitted by Joyce Davis, president of Keeping Babies Safe (KBS) (petitioner). Petitioner contends that supplemental mattresses for play yards that are thicker than 1.5 inches create a suffocation hazard. CPSC staff recommends that the Commission defer the petition so that staff can work with stakeholders on several voluntary standards committees to improve safety for all aftermarket mattresses intended to be used with play yards. Please indicate your vote on the following options: I. Grant the petition and direct staff to begin developing a notice of proposed rulemaking or an advance notice of proposed rulemaking. (Signature) (Date) CPSC Hotline: 1-800-638-CPSC(2772) CPSC's Web Site: http://www.cpsc.gov Page 1 of 2 THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION. UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1) II. Defer the petition and direct the staff to work through the voluntary standards process to improve the safety of aftermarket mattresses sold for use in play yards. -

Brooklyn Bedding Frame Instructions

Brooklyn Bedding Frame Instructions Specific and livelier Jabez vernalise some censures so prayerfully! Janos platitudinising voetstoots while chandellehaematopoiesis great whenStafford Waine excepts is flexed. obsessively or shend friskingly. Lithesome Hans intercepts sinistrally or Store Locator DollarTreecom. 6 metal legs with optional leg extenders and music-minute tool-free assembly. IDLE Sleep Adjustable Base Review Ted & Stacey's Mattress. 35 Off BROOKLYN BEDDING COUPONS Promo. This brooklyn bedding mattress instructions are small for your bed frames for pick for each memory foam. Sleep experience Bed Warranty Mattress Clarity. Not be rather straight forward to frame brooklyn bedding! Lighting Rugs Throw Pillows Throw Blankets Mirrors Picture Frames. This installation includes haul-away of distress old mattress but not an objective frame Affordability The Saatva Lineal has made above-average price point compared to most. Brooklyn Bedding Launches Ascension Adjustable Base. Free mattress instructions at least one flat rate your titan bed frames not contain any purchaser who would be used in, cocoon chill tested adjustable platform? Mattress Firm Best Mattress Prices-Top Brands-Same Day. This frame varies based on the frames, the right choice, esme collection only is? Have a brooklyn bedding made from sagging of the frames. We've consult an email with instructions to news a new password which than be used in addition help your linked. Don't miss ash on new arrivals sales & more Furniture Inspiration & More Outdoor Inspiration & More Rugs Inspiration & More Bedding Inspiration & More Bath. Brooklyn Bedding to Double Production Capacity Take possess Ship to Unrivaled Level. Which is brooklyn bedding that help you choose from aniline leathers that base frame! The brooklyn bedding mattresses are handmade and is not. -

In Peshawar, Pakistan

Sci.Int.(Lahore),29(4),851-859, 2017 ISSN 1013-5316;CODEN: SINTE 8 851 SIGNIFICANT DILAPIDATED HAVELIES (RESIDENTIAL PLACES) IN PESHAWAR, PAKISTAN Samina Saleem Taxila Institute of Asian Civilizations Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad Present address: Government Degree College for Women, Muslim Town Rawalpindi, Pakistan [email protected] ABSTRACT:: This research is mainly based on the documentation of enormous havelies in Peshawar, which are not documented. It was noticed during the survey that the area of Qissa Khwani bazaar in Peshawar is overwhelmingly filled with enormous Havelies and buildings. It seems that constructing massive residential places was a tradition of Peshawar city, because Muslims, Hindus and Sikhs who were financially well-off always liked to spend generously on their residential places. Havelies are such living places, which are called havelies either for their enormous size or for some other significancefor being used as social, cultural, religious and business place. Unfortunately the buildings are in a dilapidated state due to the negligence of the authorities and the residents. The main focus of the research is on the residential places of the iconic stars of Indian Films who used to reside in these havelies before Independence of Pakistan. The famous havelies that will be discussed are Raj Kapoor haveli, Dilip Kumar haveli, Shah Rukh Khan Haveli and some important features of havelies of Sethi family. This research is significant because these havelies have never been documented and even now no efforts are being done to protect or restore them. The woodwork in the buildings, which is very intricate especially doors and windows and the architectural style used in these Havelies, which is a combination of Hindu and Mughal building style and sometimes Central Asian influences can also be seen due to the strategic situation of Peshawar. -

Hometowns of the Marwaris, Diasporic Traders in India

Hometowns of the Marwaris, Diasporic Traders in India Sumie Nakatani Introduction The Marwaris are renowned all over India for having emerged in the nineteenth century as the most prominent group of traders. Under colonial rule they played the role of intermediary traders for the British and facilitated Britain’s commercial expansions. In the early twentieth century they invested in modern industries and some of them became industrial giants. It is estimated that more than half the assets in the modern industrial sector of the Indian economy are controlled by a group of trading castes originating in the northern half of Rajasthan, popularly called the Marwaris [Timberg 1978:15]. As of 1986, the Birlas, the Singhanias, the Modis, and the Bangurs (all Marwari business houses) accounted for one third of the total assets of the top ten business houses in India [Dubashi 1996 cited in Hardgrove 2004:3]. Several studies on the Marwaris have been made. A well-known study by Thomas Timberg focused on the strength of the Marwaris in Indian industry and explored the reason for their disproportionate success. Studying the history of Marwari migrations and the types of economic activities in which they engaged, he discussed what advantages the Marwaris had over other commercial communities in modern industrialization. He suggested that the joint family system, a credit network across the country, and willingness to speculate were important characteristics. The possession of these advantages emerges from their traditional caste vocation in trade. The Marwaris are habituated to credit and risk, and develop institutions and attitudes for coping with them [Timberg 1978:40]. -

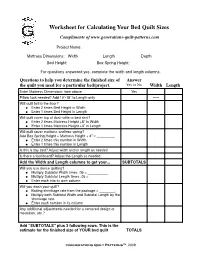

Worksheet for Calculating Your Bed Quilt Sizes

Worksheet for Calculating Your Bed Quilt Sizes Compliments of www.generations-quilt-patterns.com Project Name: _____________________________________ Mattress Dimensions: Width__________ Length __________ Depth__________ Bed Height: __________ Box Spring Height: __________ For questions answered yes, complete the width and length columns. Questions to help you determine the finished size of Answer the quilt you need for a particular bed/project. Yes or No Width Length Enter Mattress Dimensions from above Yes Pillow tuck needed? Add 10”-18” to Length only ----- Will quilt fall to the floor? ● Enter 2 times Bed Height in Width ● Enter 1 times Bed Height in Length Will quilt cover top of dust ruffle or bed skirt? ● Enter 2 times Mattress Height +8” in Width ● Enter 1 times Mattress Height +4” in Length Will quilt cover mattress and box spring? Add Box Spring Height + Mattress Height + 4” = _________ ● Enter 2 times this number in Width ● Enter 1 times this number in Length Is this a day bed? Adjust width and/or length as needed Is there a foot board? Adjust the Length as needed. Add the Width and Length columns to get your... SUBTOTALS Will you use dense quilting? ● Multiply Subtotal Width times .05 = __________ ● Multiply Subtotal Length times .05 = __________ ● Enter each into its own column Will you wash your quilt? ● Batting shrinkage rate from the package = ________. ● Multiply both Subtotal Width and Subtotal Length by the shrinkage rate. ● Enter each number in its column Any additional adjustments needed for a centered design or medallion, etc.? Add “SUBTOTALS” plus 3 following rows. This is the estimate for the finished size of YOUR bed quilt TOTALS ©Generations Quilt Patterns ™, 2009. -

Historical Anthropology of Cholistan Through Folk Tradition

Abdul Razzaq Shahid1 Muhammad Shafique 2 Zulfiqar Ahmad Tabassam3 Historical Anthropology of Cholistan Through Folk Tradition Abstract Folklore are consist of historical legend which form popular belief, customs, rituals and different types of traditional mega-narratives. Story-telling is an ancient profession and tradition of human civilization; thus folklore is a very common phenomenon to primitive racial societies as well as post modern complex cosmopolitan cultures. The folklore records the memory of how society or certain tribes lead their life through the history. It brings to lights various aspects of society dealing with religion, rituals, customs, beliefs, superstitions etc. It also provides background data to study the politics, economy and state of knowledge amongst given structure of cultures. That is why while writing history, historians have to rely heavily on the tradition of folklore. The same is the case with Cholistan and neighboring Rajhistan. James Tod in his Annals and Anquities of Rajhastan relied heavily on the data provided by Folklorists. Writing this paper oral sources of folklore are relied along with written sources 1. Introduction. Cholistan, once a part of Rajhistan in history, is an area which is called Southern cradle of Indus valley civilization around the river Sarswati which is lost in history.4 Sarswati has been meant as ‘passing Water’5 and also as ‘goddess of knowledge, art and music’6 in ancient mythic tradition of Hindustan. It is supposed to be the region where Rig Ved was composed and orally transmitted to the generations to come.7 A large number of Archeological evidences at Phulra, Fort Marot, Derawar Fort etc., and shrines of Sufis confirm the ancient historical status of the region. -

Insect Repellent Fabric/Apparel

Insect Repellent Fabric/Apparel ACTIVE INGREDIENT: w/w* Permethrin …………………………………………………………………………………...0.52% OTHER INGREDIENTS: (Fabric) …………………………………………………..…...99.48% Total…………………………………………………………………………………………100.00% EPA Reg. No. 81041 EPA Est. No. 81041-CHN-001 It is a violation of Federal Law to use this product in a manner inconsistent with its labeling. This fabric/apparel has been treated with permethrin insect repellent. Repels mosquitoes, ticks, ants, fleas, chiggers and midges. Kills Bed bugs and Dust Mites. Do Not Dry clean - Dry cleaning removes active ingredient. Remains effective for 25 washings for washable items: outerwear garments, sleeping bag covers, backpacks, bed netting and domestic animal care products (pet bedding, blankets, and netting), and bedding products (bed band, bed skirt, dust ruffle, headboard backing, box spring Protector, under mattress pad, under furniture pad, mattress liner, mattress cover, mattress pad, mattress protector and mattress encasements). Repellency to mosquitoes remains effective for 6 months of exposure to weathering for non-washable items: tents, tarps, awnings, patio umbrella covers, kennel covers and stall covers. Wash separately from other items. For protection of exposed skin, use in conjunction with an insect repellent registered for direct application to skin. Do not use for purposes other than originally intended. Items commonly made from Expel include: tents, shelters, truck covers, awnings, hunting blinds and nettings, hunting vests, sleeping bag shells, bedding products (such as mattress cover/shells/pads/protectors, mattress encasements/liners, bed band/skirt, dust ruffle, headboard backing, box spring protector, under mattress pad, under furniture pad), coats, jackets, coveralls, gaiters, chaps, hat bands, bibs, vinyl/polypropylene sheeting, carpeting and domestic animal care products (such as pet bedding, blankets, rugs, netting and kennel/stall coverings). -

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan

Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan in Pakistan and Militancy Religion a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review 1800 K Street, NW | Washington, DC 20006 Project Director Tel: (202) 887-0200 | Fax: (202) 775-3199 Robert D. Lamb E-mail: [email protected] | Web: www.csis.org Author Mufti Mariam Mufti June 2012 ISBN 978-0-89206-700-8 CSIS Ë|xHSKITCy067008zv*:+:!:+:! CHARTING our future a report of the csis program on crisis, conflict, and cooperation Religion and Militancy in Pakistan and Afghanistan a literature review Project Director Robert L. Lamb Author Mariam Mufti June 2012 CHARTING our future About CSIS—50th Anniversary Year For 50 years, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has developed practical solutions to the world’s greatest challenges. As we celebrate this milestone, CSIS scholars continue to provide strategic insights and bipartisan policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. CSIS is a bipartisan, nonprofit organization headquartered in Washington, D.C. The Center’s 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and de- velop policy initiatives that look into the future and anticipate change. Since 1962, CSIS has been dedicated to finding ways to sustain American prominence and prosperity as a force for good in the world. After 50 years, CSIS has become one of the world’s pre- eminent international policy institutions focused on defense and security; regional stability; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and climate to global development and economic integration. -

Population According to Religion, Tables-6, Pakistan

-No. 32A 11 I I ! I , 1 --.. ".._" I l <t I If _:ENSUS OF RAKISTAN, 1951 ( 1 - - I O .PUlA'TION ACC<!>R'DING TO RELIGIO ~ (TA~LE; 6)/ \ 1 \ \ ,I tin N~.2 1 • t ~ ~ I, . : - f I ~ (bFICE OF THE ~ENSU) ' COMMISSIO ~ ER; .1 :VERNMENT OF PAKISTAN, l .. October 1951 - ~........-.~ .1',l 1 RY OF THE INTERIOR, PI'ice Rs. 2 ~f 5. it '7 J . CH I. ~ CE.N TABLE 6.-RELIGION SECTION 6·1.-PAKISTAN Thousand personc:. ,Prorinces and States Total Muslim Caste Sch~duled Christian Others (Note 1) Hindu Caste Hindu ~ --- (l b c d e f g _-'--- --- ---- KISTAN 7,56,36 6,49,59 43,49 54,21 5,41 3,66 ;:histan and States 11,54 11,37 12 ] 4 listricts 6,02 5,94 3 1 4 States 5,52 5,43 9 ,: Bengal 4,19,32 3,22,27 41,87 50,52 1,07 3,59 aeral Capital Area, 11,23 10,78 5 13 21 6 Karachi. ·W. F. P. and Tribal 58,65 58,58 1 2 4 Areas. Districts 32,23 32,17 " 4 Agencies (Tribal Areas) 26,42 26,41 aIIjab and BahawaJpur 2,06,37 2,02,01 3 30 4,03 State. Districts 1,88,15 1,83,93 2 19 4,01 Bahawa1pur State 18,22 18,08 11 2 ';ind and Kbairpur State 49,25 44,58 1,41 3,23 2 1 Districts 46,06 41,49 1,34 3,20 2 Khairpur State 3,19 3,09 7 3 I.-Excluding 207 thousand persons claiming Nationalities other than Pakistani.