Papers from the British Criminology Conference 2012 Whole Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Socio-Economic and Political Consequences of Economic Sanctions for Target and Third-Party Countries

Socio-Economic and Political Consequences of Economic Sanctions for Target and Third-Party Countries Dursun Peksen, Ph.D. Assistant Professor University of Memphis Possible Effects of Economic Sanctions on Human Rights, Democratic Freedoms, and Press Freedom in Target Countries Economic sanctions fail between 65-95% of the time in achieving their intended goals. Evidence suggests sanctions are also counterproductive in advancing human rights, democracy, and press freedom. Why? 1. Imposed sanctions often fail to impair the capacity of the government in part because the target elites might respond to foreign pressure by: * changing their public spending priorities by shifting public resources to military equipment and personnel to enhance their coercive capacity * redirecting the scarce resources and services to its supporters such as those in police, military, and civil services to maintain their loyalty and support; and * actively involving themselves in sanction busting activities through illegal smuggling and other underground transnational economic channels. Thus, trade and financial restrictions imposed on the target government are unlikely to exact significant damage on the coercive capacity of the government to induce behavioral change from the targeted elites. 2. When an external actor demands political reforms from another regime, the targeted leadership usually perceives the foreign pressure as a threat to sovereignty and particularly to regime survival. To mitigate any possible domestic “audience costs” caused by conceding to the sanctions, the regime has an incentive to put greater pressure on opposition groups to show its determination against any external pressure for reform and policy change. Socio-economic and Political Effects of Sanctions on the Vulnerable Segments (Women, Children, and Minorities) of Target Populations Sanctions, conditional on the severity of the coercion, might cause significant civilian pain by worsening public health conditions, economic well-being, and physical security of the populace in target countries. -

Organised Crime Around the World

European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) P.O.Box 161, FIN-00131 Helsinki Finland Publication Series No. 31 ORGANISED CRIME AROUND THE WORLD Sabrina Adamoli Andrea Di Nicola Ernesto U. Savona and Paola Zoffi Helsinki 1998 Copiescanbepurchasedfrom: AcademicBookstore CriminalJusticePress P.O.Box128 P.O.Box249 FIN-00101 Helsinki Monsey,NewYork10952 Finland USA ISBN951-53-1746-0 ISSN 1237-4741 Pagelayout:DTPageOy,Helsinki,Finland PrintedbyTammer-PainoOy,Tampere,Finland,1998 Foreword The spread of organized crime around the world has stimulated considerable national and international action. Much of this action has emerged only over the last few years. The tools to be used in responding to the challenges posed by organized crime are still being tested. One of the difficulties in designing effective countermeasures has been a lack of information on what organized crime actually is, and on what measures have proven effective elsewhere. Furthermore, international dis- cussion is often hampered by the murkiness of the definition of organized crime; while some may be speaking about drug trafficking, others are talking about trafficking in migrants, and still others about racketeering or corrup- tion. This report describes recent trends in organized crime and in national and international countermeasures around the world. In doing so, it provides the necessary basis for a rational discussion of the many manifestations of organized crime, and of what action should be undertaken. The report is based on numerous studies, official reports and news reports. Given the broad topic and the rapidly changing nature of organized crime, the report does not seek to be exhaustive. -

The Political Economy of Economic Sanctions*

Chapter 27 THE POLITICAL ECONOMY OF ECONOMIC SANCTIONS* WILLIAM H. KAEMPFER Academic Affairs, Campus Box 40, University of Colorado, Boulder, Boulder, CO 80309-0040, USA e-mail: [email protected] ANTON D. LOWENBERG Department of Economics, California State University, Northridge, 18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330-8374, USA e-mail: [email protected] Contents Abstract 868 Keywords 868 1. Introduction 869 2. Economic effects of sanctions 872 3. The political determinants of sanctions policies in sender states 879 4. The political effects of sanctions on the target country 884 5. Single-rational actor and game theory approaches to sanctions 889 6. Empirical sanctions studies 892 7. Political institutions and sanctions 898 8. Conclusions and avenues for further research 903 References 905 * The authors thank Keith Hartley, Irfan Nooruddin and Todd Sandler for valuable comments. Derek Lowen- berg provided technical assistance in preparation of the final manuscript. All errors remain the responsibility of the authors alone. Handbook of Defense Economics, Volume 2 Edited by Todd Sandler and Keith Hartley © 2007 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved DOI: 10.1016/S1574-0013(06)02027-8 868 W.H. Kaempfer and A.D. Lowenberg Abstract International economic sanctions have become increasingly important as alternatives to military conflict since the end of the Cold War. This chapter surveys various approaches to the study of economic sanctions in both the economics and international relations literatures. Sanctions may be imposed not to bring about maximum economic damage to the target, but for expressive or demonstrative purposes. Moreover, the political effects of sanctions on the target nation are sometimes perverse, generating increased levels of political resistance to the sanctioners’ demands. -

TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-Wing *

116TH INTERNATIONAL TRAINING COURSE VISITING EXPERTS’ PAPERS TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-wing * I. INTRODUCTION This paper will draw heavily on the experience gained by law enforcement Triad societies are criminal bodies in the HKSAR in tackling the triad organisations and are unlawful under the problem. Emphasis will be placed on anti- Laws of Hong Kong. Triads have become a triad law and Police enforcement tactics. matter of concern not only in Hong Kong, Background knowledge on the structure, but also in other places where there is a beliefs and rituals practised by the triads sizable Chinese community. Triads are is important in order to gain an often described as organized secret understanding of the spread of triads and societies or Chinese Mafia, but these are how triads promote illegal activities by simplistic and inaccurate descriptions. resorting to triad myth. With this in mind Nowadays, triads can more accurately be the paper will examine the following issues: described as criminal gangs who resort to triad myth to promote illegal activities. • History and Development of Triads • Triad Hierarchy and Structure For more than one hundred years triad • Characteristics of Triads activities have been noted in the official law • Differences between Triads, Mafia and police reports of Hong Kong. We have and Yakuza a long history of special Ordinances and • Common Crimes Committed by related legislation to deal with the problem. Triads The first anti-triad legislation was enacted • Current Triad Situation in Hong in 1845. The Hong Kong Special Kong Administrative Region (HKSAR) has, by • Anti-triad Laws in Hong Kong far, the longest history, amongst other • Police Enforcement Strategy jurisdictions, in tackling the problem of • International Cooperation triads and is the only jurisdiction in the world where specific anti-triad law exists. -

Economic Sanctions and Globalization: Assessing the Impact of the Globalization Level of Target State on Sanctions Efficacy1

Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting – JEFA (2019), Vol.6(1). p.41-54 Duzcu ECONOMIC SANCTIONS AND GLOBALIZATION: ASSESSING THE IMPACT OF THE GLOBALIZATION LEVEL OF TARGET STATE ON SANCTIONS EFFICACY1 DOI: 10.17261/Pressacademia.2019.1027 JEFA- V.6-ISS.1-2019(4)-p.41-54 Murad Duzcu Hatay Mustafa Kemal University, Department of International Relations, Tayfur Sökmen Kampüsü, 31060, Antakya, Hatay, Turkey. [email protected] , ORCID: 0000-0001-5587-4774 Date Received: November 30, 2018 Date Accepted: March 18, 2019 To cite this document Duzcu, M. (2019). Economic sanctions and globalization: Assessing the impact of the globalization level of target state on sanctions efficacy. Journal of Economics, Finance and Accounting (JEFA), V.6(1), p.41-54. Permemant link to this document: http://doi.org/10.17261/Pressacademia.2019.1027 Copyright: Published by PressAcademia and limited licenced re-use rights only. ABSTRACT Purpose - When do states resist the threat of sanctions or comply with the demands of the political unit imposing sanctions? This article argues that if the target has a high globalization index, it conforms to the demands of the sender. Therefore, the article examines the impact of target’s globalization level on the initiation and success of economic sanctions as a frequently used foreign policy tool. Methodology - In combination of two datasets, (for sanctions cases, Hufbauer et al, 2007; and for globalization index Raab et al, 2007), this article, uses 72 sanctions cases from Hufbauer et al. (2007) dataset to examine some indicators of sanctions efficacy. A probit model is used to analyze the hypotheses. -

Export Controls and Economic Sanctions

BUSINESS REGULATION Export Controls and Economic Sanctions JAMES W REED, ALAN WH. GOURLEY, LORRAINE B. HALLOWAY, AND JEFFREY L. SNYDER* I. Introduction Changes in U.S. export controls and economic sanctions during the year 2003 were largely a reflection of three main forces that shaped U.S. security policy: (1) the war in Iraq; (2) continued efforts to deny financial and logistical support to terrorist groups; and (3) a renewed emphasis on stemming the flow of sensitive products and technologies to proli- ferators of weapons of mass destruction. These three themes played out not only in new regulations and policies emanating from the three principal agencies that regulate activity in this area-the Departments of Commerce, State, and Treasury-but they were evident in more aggressive patterns of export enforcement activity. In the sections that follow, we adopt the framework of previous year-end summaries in this journal to trace the highlights of regulatory developments that affected economic sanc- tions and export controls during 2003. While this brief survey does not offer a compendium of all of the developments in this area over the past year, the summaries below describe noteworthy developments that warrant the attention of practitioners in this field. II. Trade and Economic Sanctions A. IRAQ As the United States and its coalition parmers brought major hostilities to a close in Iraq, governments and international organizations strained to adjust the multinational embargo on Iraq to match the realities on the ground. A necessary predicate was achieved when the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 1483, which formally lifted all UN sanctions, except those that related to the sale and supply to Iraq of arms and material.' Immediately thereafter, the Treasury Department's Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) issued a new General License on May 23, 2003, which substantially-although not completely-lifted the U.S. -

International Economic Sanctions: Improving the Haphazard U.S. Legal Regime

Georgetown University Law Center Scholarship @ GEORGETOWN LAW 1999 International Economic Sanctions: Improving the Haphazard U.S. Legal Regime Barry E. Carter Georgetown University Law Center This paper can be downloaded free of charge from: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1585 Barry E. Carter, International Economic Sanctions: Improving the Haphazard U.S. Legal Regime, 75 Cal. L. Rev. 1159 (1987) This open-access article is brought to you by the Georgetown Law Library. Posted with permission of the author. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub Part of the International Law Commons California Law Review VOL. 75 JULY 1987 No. 4 Copyright © 1987 by California Law Review, Inc. International Economic Sanctions: Improving the Haphazard U.S. Legal Regime Barry E. Carter TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE I. INTRODUCTION ........................................... 1163 Scope of the Article ....................................... 1166 II. THE PURPOSES AND EFFECTIVENESS OF ECONOMIC SANCTIONS ................................................ 1168 A. The Purposes of Sanctions ............................. 1170 B. Effectiveness of Sanctions .............................. 1171 1. Effectiveness as a Function of Purpose .............. 1173 2. Effectiveness of Sanctions by Type .................. 1177 3. Costs to the Sender Country ....................... 1180 III. THE NONEMERGENCY LAWS .............................. 1183 A. Bilateral Government Programs........................ 1183 B. Exports from the United -

Economic Sanctions Against Human Rights Violations Buhm Suk Baek J.S.D

Cornell Law Library Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository Cornell Law School Inter-University Graduate Conferences, Lectures, and Workshops Student Conference Papers 4-14-2008 Economic Sanctions Against Human Rights Violations Buhm Suk Baek J.S.D. candidate, Cornell Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/lps_clacp Part of the Economics Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, and the International Law Commons Recommended Citation Baek, Buhm Suk, "Economic Sanctions Against Human Rights Violations" (2008). Cornell Law School Inter-University Graduate Student Conference Papers. Paper 11. http://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/lps_clacp/11 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Conferences, Lectures, and Workshops at Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Cornell Law School Inter-University Graduate Student Conference Papers by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Cornell Law: A Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ECONOMIC SANCTIONS AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS By Buhm-Suk Baek* March 2008 * Candidate for J.S.D., Cornell Law School; I am deeply grateful to Professor Muna Ndulo. Without his sincere advice and comments, I could not complete this paper. I would like to extend my thanks to Professor David Wippman for his valuable advices. My deepest appreciation also goes to Kornelia Tancheva for her valuable instructions on this paper. Foremost, I would like to thank my father, KwangSun Baek, to whom I dedicate this paper. ECONOMIC SANCTIONS AGAINST HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS Buhm-Suk Baek ABSTRACT The idea of human rights protection, historically, has been considered as a domestic matter, to be realized by individual states within their domestic law and national institutions. -

THE ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES of ECONOMIC SANCTIONS on the ENJOYMENT of HUMAN RIGHTS by Em

THE ADVERSE CONSEQUENCES OF ECONOMIC SANCTIONS ON THE ENJOYMENT OF HUMAN RIGHTS by Em. Prof. Dr. Marc BOSSUYT President of the Constitutional Court of Belgium 1. The working document (E/CN.4/Sub.2/2000/33), prepared “without financial implications” as requested by the UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Minorities on 26 August 1999 in its decision 1999/111 of 26 August 1999, was presented to the Sub- Commission on 16 August 2000. This was the follow-up to resolution 1997/35 of 28 August 1997, in which the Sub-Commission had stressed four specific points concerning such measures: “(i) They should always be limited in time (fourth preambular paragraph); (ii) They most seriously affect the innocent population, especially the most vulnerable (fifth preambular paragraph); (iii) They aggravate imbalances in income distribution (sixth preambular paragraph); (iv) They generate illegal and unethical business practices (seventh preambular paragraph)”. 2. With regard to the nature of the actions undertaken, a brief classification of sanctions was provided : (i) Two basic forms of economic sanctions: (a) Trade sanctions restricting imports and exports to and from the target country; (b) Financial sanctions addressing monetary issues. (ii) Other forms of sanctions include: (a) Sanctions against the travel of certain individuals or groups and sanctions against certain kinds of air transport; (b) Military sanctions including arms embargoes and the termination of military assistance or training; (c) Diplomatic sanctions revoking visas of diplomats and political leaders; (d) Cultural sanctions banning athletes from international sports competitions and artists from international events. 3. A six-pronged test to evaluate sanctions was proposed: (i) Are the sanctions imposed for valid reasons? Sanctions under the United Nations system must be imposed only when there is a threat of or actual breach of international peace and security. -

Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples

Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples September 2014 RACE in Europe Project Partners Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples “With the financial support of the Prevention of and Fight against Crime Programme European Commission- Directorate-General Home Affairs” ISBN 978–0–900918–91–0 Acknowledgements and contributors This publication was made possible by the information and advice provided by the RACE in Europe project partners and a variety of individuals, agencies and organisations across Europe, who have shared their experience, and agreed to be interviewed or to take part in focus groups. Our thanks go to all RACE in Europe seminar participants who provided information through interviews, questionnaires and group discussions. Anti-Slavery would like to thank in particular Vicky Brotherton, Fiona Waters, Marie Jelinkova, Grainne O’Toole, Viginija Petruskaite, Chloe Setter, Klara Skrivankova, Bernie Gravett, Michal Krebs and Walter Hilhorst for researching, writing and contributing their expertise and information for this publication. RACE in Europe project partner profiles UK Anti-Slavery International: Anti-Slavery International is the oldest human rights organisation in the world. The NGO works at the local, regional and international level to eliminate all forms of slavery around the world. www.antislavery.org ECPAT UK: ECPAT’s activities involve research, campaigning and lobbying government to prevent child exploitation and protect children in tourism and child victims of trafficking. www.ecpat.org.uk Specialist Policing Consultancy: Specialist Policing Consultancy provides expertise in combatting organised crime at an international level. -

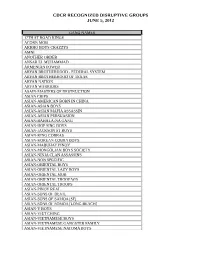

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON -

L'utilisation Des Sites De Réseautage

ARCHIVED - Archiving Content ARCHIVÉE - Contenu archivé Archived Content Contenu archivé Information identified as archived is provided for L’information dont il est indiqué qu’elle est archivée reference, research or recordkeeping purposes. It est fournie à des fins de référence, de recherche is not subject to the Government of Canada Web ou de tenue de documents. Elle n’est pas Standards and has not been altered or updated assujettie aux normes Web du gouvernement du since it was archived. Please contact us to request Canada et elle n’a pas été modifiée ou mise à jour a format other than those available. depuis son archivage. Pour obtenir cette information dans un autre format, veuillez communiquer avec nous. This document is archival in nature and is intended Le présent document a une valeur archivistique et for those who wish to consult archival documents fait partie des documents d’archives rendus made available from the collection of Public Safety disponibles par Sécurité publique Canada à ceux Canada. qui souhaitent consulter ces documents issus de sa collection. Some of these documents are available in only one official language. Translation, to be provided Certains de ces documents ne sont disponibles by Public Safety Canada, is available upon que dans une langue officielle. Sécurité publique request. Canada fournira une traduction sur demande. L’utilisation des sites de réseautage social à des fins criminelles : Étude et analyse du phénomène de « cyberbanging » Par Carlo Morselli, Ph. D. Université de Montréal et David Décary-Hétu Université de Montréal préparée pour la Division de la recherche et de la coordination nationale sur le crime organisé Secteur de la police et de l’application de la loi Sécurité publique Canada Les opinions exprimées n’engagent que les auteurs et ne sont pas nécessairement celles du ministère de la Sécurité publique.