Pliny's Province1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rome and Near Eastern Kingdoms and Principalities, 44-31 BC: a Study of Political Relations During Civil War

Durham E-Theses Rome and Near Eastern Kingdoms and Principalities, 44-31 BC: A Study of Political Relations During Civil War VAN-WIJLICK, HENDRIKUS,ANTONIUS,MARGAR How to cite: VAN-WIJLICK, HENDRIKUS,ANTONIUS,MARGAR (2013) Rome and Near Eastern Kingdoms and Principalities, 44-31 BC: A Study of Political Relations During Civil War , Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/9387/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ROME AND NEAR EASTERN KINGDOMS AND PRINCIPALITIES, 44-31 BC A study of political relations during civil war Hendrikus Antonius Margaretha VAN WIJLICK Abstract This thesis presents a critical analysis of the political relations between Rome on the one hand and Near Eastern kingdoms and principalities on the other hand during the age of civil war from 44 until 31 BC. -

Graeco-Roman Associations, Judean Synagogues and Early Christianity in Bithynia-Pontus*

chapter 3 Graeco-Roman Associations, Judean Synagogues and Early Christianity in Bithynia-Pontus* Markus Öhler As has been shown in numerous studies, early Christian communities as well as synagogues of Judeans resemble Graeco-Roman associations in form and structure. Therefore, it makes sense to examine Christ groups from the first three centuries from the perspective of associations and synagogues in order to grasp the various characteristics of Christianity in this area up until the reign of Constantine. This article will begin with a brief geographical and historical overview of the regions composing the double province of Bithynia-Pontus, continue with a review of the inscriptional and literary evidence on associa- tions (including synagogues), and finally discuss early sources for a study of Christianity, namely, the New Testament, Pliny’s letter about Christians, and inscriptions from the second and third centuries with a potentially Christian background. 1 Bithynia and Pontus: The Area and Its History in Early Imperial Times The area of Bithynia et Pontus, which partly includes the region of Paphlagonia, has had a chequered history.1 In what follows, I will roughly focus on the territo- ries which formed a Roman double province from 63BC onward. This includes, from west to east, the region of Bithynia (from Kalchedon to Klaudiopolis and Tieion), Paphlagonia (from Amastris to Sinope), and Pontus (from Amisos to Nikopolis). Pontus had been a kingdom from Mithradates I until the death of Mithra- dates VI in 63BC. Afterwards, the western part, reaching as far as the city of Nikopolis, became part of the Roman province of Bithynia et Pontus which * Many thanks to Julien M. -

The Local Impact of the Koinon in Roman Coastal Paphlagonia Chingyuan Wu University of Pennsylvania, [email protected]

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 The Local Impact Of The Koinon In Roman Coastal Paphlagonia Chingyuan Wu University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Wu, Chingyuan, "The Local Impact Of The Koinon In Roman Coastal Paphlagonia" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3204. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3204 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3204 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Local Impact Of The Koinon In Roman Coastal Paphlagonia Abstract This dissertation studies the effects that a “koinon” in the Roman period could have on its constituent communities. The tudys traces the formation process of the koinon in Roman coastal Paphlagonia, called “the Koinon of the Cities in Pontus,” and its ability to affect local customs and norms through an assortment of epigraphic, literary, numismatic and archaeological sources. The er sults of the study include new readings of inscriptions, new proposals on the interpretation of the epigraphic record, and assessments on how they inform and change our opinion regarding the history and the regional significance of the coastal Paphlagonian koinon. This study finds that the Koinon of the Cities in Pontus in coastal Paphlagonia was a dynamic organisation whose membership and activities defined by the eparchic administrative boundary of the Augustan settlement and the juridical definition of the Pontic identity in the eparchic sense. The necessary process that forced the periodic selection of municipal peers to attain koinon leadership status not only created a socially distinct category of “koinon” elite but also elevated the koinon to extraordinary status based on consensus in the eparchia. -

Turkey's Unexcavated Synagogues: Could The

34 JULY/AUGUST 2012 BAR SPECIALIZES IN arTICLES abOUT SITES that have been excavated, featuring the often dra- matic finds archaeologists uncover. But what about finds from sites that have not been excavated (and should be)? We know a lot about the Jews of Cilicia from the New Testament and other ancient sources. Before becoming a follower of Jesus, Paul was a devout Jew from Tarsus, the capital of the Roman province of Cilicia in southeast Anatolia (modern Turkey). Despite the presence of Jews in Cilicia, however, relatively little is known about their syna- gogues. Indeed not a single ancient synagogue has been excavated in Cilicia. I think I may have found two of them—at Korykos and at Çatiören. The presence of Jews in Cilicia during the Hel- lenistic and Roman periods is well established in both ancient literature and epigraphical remains. Paraphrasing (or creating) a speech by the first- century A.D. Judean king Agrippa I to the Roman emperor Gaius Caligula (37–41 A.D.), the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria records a state- ment that the city of Jerusalem was responsible for founding numerous colonies throughout the Mediterranean world, including cities in the Ana- tolian regions of Cilicia, as well as Pamphylia, Asia, Bithynia and Pontus.1 Regardless of whether or not Philo accurately reproduced the substance of Agrippa’s speech, Philo could not have included such a statement if Jewish settlements had not been well established in those regions prior to his own time. Later in the first century, the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus referred to Alexander (the son of Tigranes, a Jewish king of Armenia) who was appointed king of Ketis in Cilicia by the Roman emperor Vespasian.2 The appointment of a Jew to this position is very probably an indication of a large Jewish presence in the region. -

The Churches of Asia Minor Article for Unit 1

4 5 The Churches of Asia Minor Article for Unit 1 N THE SUMMER OF 1978 my wife and I, along with like Timothy and Titus. In brief, it appears that consider- Iour two sons who were teenagers at the time, spent able church planting was carried out in the province of three weeks tent-camping throughout Turkey. My family Asia, under Paul’s direction from Ephesus, during his enjoyed the adventure, and—as part of a larger research third missionary journey. project—I had opportunity to visit personally many an- cient sites of considerable importance in the New Testa- Peter: A Letter to Christians in Asia Minor ment. First Peter is addressed to “God’s elect, strangers in The western half of modern-day Turkey corresponds the world, scattered throughout Pontus, Galatia, Cappa- to a wide geographical area called Asia Minor in the docia, Asia and Bithynia” (1 Peter 1:1). We do not know first century. The Romans organized this vast area into whether Peter ever personally travelled these areas in four official “provinces”: Galatia, Cappadocia, and Asia; Asia Minor. If not, it is obvious he had direct sources of Bithynia and Pontus were combined into a fourth large information concerning his addressees from others who province (all named in 1 Peter 1:1). had. Mark is named in 1 Peter 5:13. He had been a com- panion of Paul and Barnabas on the beginning leg of the Paul: Church Planting in Asia Minor first missionary journey (Acts 12:25). Later, he became The good news reached parts of this region prior to a close associate of the apostle Peter; Peter called him Paul’s three missionary journeys. -

Epidemic Smallpox, Roman Demography, and the Rapid Growth Of

Epidemic Smallpox, Roman Demography, and the Rapid Growth of Early Christianity, 160 CE to 310 CE Kenneth J. Philbrick Undergraduate Senior Thesis Department of History Columbia University April 2014 Professor William V. Harris, advisor Professor Richard Billows, second reader Professor Marco Maiuro Many thanks to Professor William Harris for all the help and guidance he provided, and to Professor Richard Billows for his insightful critiques which led me to reshape much of my argument, and to Professor Marco Maiuro, who led the seminar in which my ideas for this paper first took shape, and who was very supportive and helpful in the early stages of my research.! Table of Contents Introduction and Motivation for Research ................................................................................. 1! The Great Pestilence ................................................................................................................... 3! Hypotheses of a Plague-Christianity Interaction ...................................................................... 12! Evidence of Infant Exposure .................................................................................................... 18! Greco-Roman Sex Ratios ......................................................................................................... 33! The Christian Demographic Profile .......................................................................................... 42! Plague and Sex Ratios ............................................................................................................. -

Coppersmith at Kayseri, Turkey. Producing Quality Copper Products

The Early Spread of Christianity Part of the oldest and most famous road of the Roman Empire, the Appian Way. This served as the main route between Rome and Greece. More than 350 miles long, the Coppersmith at road was con- Kayseri, Turkey. structed in the 4th Producing quality cent. B.C. by the copper products Roman magistrate, is a tradition in Appius Claudius the area that goes Caecus. ILLUSTRATOR PHOTO/ BOB SCHATZ back centuries. (20/9/7) COREL PHOTO PHOTO/ BRENT BRUCE (60/0212) ILLUSTRATOR © 2012 JupiterImages Corporation ETB: 1 Peter 1:1-12 Bithynia and Pontus By G. Al Wright, Jr. Early History in 560 b.c. Cyrus the Great defeated People from Thrace moved east and Croesus and made Bithynia part of O BE COMMITTED, settled into Bithynia in the sixth cen- the Persian Empire. Although it oper- truly committed, to the gos- tury b.c. King Croesus of Lydia came ated mainly as an independent region, Tpel of Jesus Christ is to be through and conquered the territory Bithynia remained part of the Persian concerned about people—those Right: Epitaph near and those far away. That con- of a sailor from cern has to be both for persons Bithynia reads: who are not followers of Christ “To the gods of the underworld. and for those who are. Tragically, For Titus Laelius many today who are Christ follow- Crispus, a sailor ers are hurting and facing opposi- with the imperial fleet at Misenum tion and even persecution. What assigned to the tri- is true today was true in the first reme Freedom. -

ROMAN PHRYGIA: Cities and Their Coinage

ROMAN PHRYGIA: Cities and their Coinage Andrea June Armstrong, PhD, University College London. Abstract of Thesis Roman Phrygia: Cities and their Coinage The principal focus of this thesis is the Upper Maeander Valley in Phrygia, which is now part of modern Turkey, and in particular three cities situated in that region, namely Laodicea, Hierapolis and Colossae. The main source used is the coinage produced by these cities with the aim of determining how they viewed their place within the Roman Empire and how they reacted to the realities of Roman rule. Inscriptional, architectural and narrative sources are also used as well as comparative material from other Phrygian and Asian cities. In order to achieve its aim, the thesis is divided into two parts. Part One details the history of Laodicea, Hierapolis and Colossae and explains the coinage system in use within the province of Asia on a regional and a civic level. The final chapter in the first part of the thesis introduces the theme of the interaction between city, region and empire which is developed more fully in Part Two. Part Two discusses the types used on the coins of the cities of the Upper Maeander Valley in the context of the cultural and religious circumstances of Rome and also in reaction to the organisational and political changes affecting the province of Asia as well as the Empire as a whole. The main conclusions of the thesis are that the cities of Laodicea, Hierapolis and Colossae were very aware of Rome and of their own status, as well as that of their province, within the Roman Empire especially in the context of ongoing circumstances and developments within the Empire. -

Identity in Pontus from the Achaemenids Through the Roman Period

IDENTITY IN PONTUS FROM THE ACHAEMENIDS THROUGH THE ROMAN PERIOD A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF MIDDLE EAST TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY BY SELİN GÜR IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE OF SETTLEMENT ARCHAEOLOGY JUNE 2018 ii Approval of the Graduate School of Social Sciences _________________ Prof. Dr. Tülin Gençöz Director I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science of Philosophy. _________________ Prof. Dr. D. Burcu Erciyas Head of Department This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science of Philosophy. _________________ Prof. Dr. D. Burcu Erciyas Supervisor Examining Committee Members Prof. Dr. Suna Güven (METU, AH) ____________ Prof. Dr. D. Burcu Erciyas (METU, SA) ____________ Asst. Prof. Dr. Şahin Yıldırım (Bartın Uni., Ark.) ____________ iv I hereby declare that all information in this document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work. Name, Last Name: Selin Gür Signature: iii ABSTRACT IDENTITY IN PONTUS FROM THE ACHAEMENIDS THROUGH THE ROMAN PERIOD Gür, Selin Master’s Thesis, Settlement Archaeology Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Deniz Burcu Erciyas June 2018, 105 Pages The Kingdom of Pontus ruled over the Black Sea Region from 302 to 64 B.C. -

TURNER-MASTERS-REPORT.Pdf (721.5Kb)

Copyright by Abigail Turner 2010 This Report committee for Abigail Turner Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: Inventing Trajan: The Construction of the Emperor’s Image in Book 10 of Pliny the Younger’s Letters APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE : Supervisor: __________________________________________ Jennifer Ebbeler __________________________________________ Andrew Riggsby Inventing Trajan: The Construction of the Emperor’s Image in Book 10 of Pliny the Younger’s Letters by Abigail Turner, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of the University of Texas at Austin In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2010 Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my parents Pamela and Garrison Turner because of their unending support and encouragement, without which my work would not be possible. Thank you mom and dad. I love you. Acknowledgements I would like to acknowledge the many hours my diligent and gracious supervisor, Dr. Jennifer Ebbeler, spent discussing Pliny’s letters and working through the scholarship and issues surrounding Pliny and Trajan with me. Born out of a seminar paper in a class on Pliny’s Letters taught by Dr. Ebbeler in the Fall of 2009, this report was inspired by my growing fascination with the letters, especially Book 10, and my numerous conversations with Dr. Ebbeler about the relationship between Pliny and Trajan. I appreciate Dr. Ebbeler’s patience, thoughtfulness and understanding beyond measure and this project would not be what it is today without her guidance. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Bithynia: History and Administration to the Erne of Pliny the Younger

University of Alberta Bithynia: History and Administration to the Erne of Pliny the Younger Stanley Jonathon Storey O A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfullment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Ancient History Department of History and Classics Edmonton, Alberta Fa11 1998 National Library Bibliothèque nationale du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Senrices services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellington OttawaON K1A ON4 OttawaON KIAW canada canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Lhrary of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distriiute or seU reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés - reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Abstract Bithynia is a region in Asia Minor, in modem day Turkey. Bithynia existed as a kingdom well before any involvernent with the Romans. As the Roman Empire expanded, Bithynia became another of her border provinces. In this thesis this region is examined fiom its earlier history onward. -

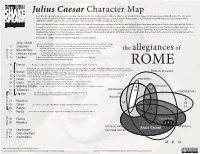

Julius Caesar Character Map the Allegiances Of

Julius Caesar Character Map In 59 BCE, attempting to bring together Pompey and Crassus, the two duelling consuls of Rome, Julius Caesar won both their support in becoming consul himself, and the three began to rule as the First Triumvirate. Further solidifying their alliance was the marriage of Caesar’s daughter from his rst marriage, Julia to Pompey (his fourth marriage). Julia, however, died in childbirth in 54 BCE, and when Crassus was killed in a military defeat in 53 BCE, the Triumvirate was over. Caesar attempted to keep a family bond with Pompey by oering his grandniece as another wife, but Pompey declined, instead marrying the widow of Crassus’ son, who had died in battle. Pompey was elected solo consul in 52 BCE, while Caesar was conquering Gaul for Rome. When Caesar returned in 49 BCE, he was told to leave his army at the Rubicon River. Refusing to do so, the Roman Civil War between Pompey and Caesar began. Caesar drove Pompey from Rome and to Egypt, where he was murdered in 48 BCE. Pompey’s followers and Caesar’s enemies continued the civil war for another three years, after which Caesar had defeated the remainder of Pompey’s followers (and family), had captured and pardoned most of his enemies, and had journeyed to Egypt and began an aair with Cleopatra. In September 45 BCE, a 56 year-old Caesar returned to Rome in triumph... Julius Caesar Calpurnia, the daughter of Piso, a supporter of Pompey, wedded Caesar in 59 BCE, as a political marriage. 2 Calpurnia Though claiming to be neutral, Piso supported Pompey in the civil war.