Download Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

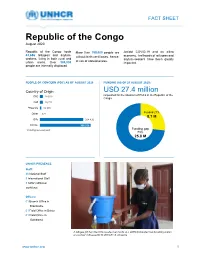

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

Why Is the African Economic Community Important? Mr

House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Hearing on “Will there be an African Economic Community?” January 9, 2014 Amadou Sy, Senior Fellow, Africa Growth Initiative, the Brookings Institution Chairman Smith, Ranking Member Bass, and Members of the Subcommittee, I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for convening this important hearing to discuss Africa’s progress towards establishing an economic community. I appreciate the invitation to share my views on behalf of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution. The Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution delivers high-quality research on issues of economic growth and development from an African perspective to better inform policy research. I have recently joined AGI from the International Monetary Fund’s where I led or participated in a number of missions to Africa over the past 15 years. Why is the African Economic Community Important? Mr. Chairman, before we start answering the main question, “Will there be an Africa Economic Community?” it is important to look at the reasons why a regionally integrated Africa is beneficial to African nations as well as the United States. In spite of its remarkable economic performance over the past decade, Africa needs to grow faster in order to transform its economy and create the resources needed to reduce poverty. Over the past 10 years, sub-Saharan Africa’s real GDP grew by 5.6 percent per year, a much faster rate than the world economy, which grew by 3.2 percent. At this rate of 5.6 percent, the region should double the size of its economy in about 13 years. -

Republic of the Congo

UNITED NATIONS CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEAL FOR THE REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000 November 1999 UNITED NATIONS For additional copies, please contact: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Complex Emergency Response Branch (CER-B) Palais des Nations 8-14 Avenue de la Paix CH - 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Tel.: (41 22) 917.1972 Fax: (41 22) 917.0368 E-Mail: [email protected] This document is also available on http://www.reliefweb.int/ iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Table 1: Total Funding Requirement – By Sector and Appealing 2 Agency…………...… CONTEXT………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Table 2: Effects of the Wars 1997 – 4 1999……..………………………………...………. 5 Table 3: ROC 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Urgan or Rural Origin… POLITICS, ECONOMY AND SECURITY……………………………………………………………. 5 Analysis, Scenarios and Response…….………………………………………………….. 7 A COMMON HUMANITARIAN ACTION PLAN (CHAP) TWO SCENARIOS………………………… 7 SCENARIO I……………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Table 4: 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Place of Origin and Present Location……………………………………………………………………...…… 9 SCENARIO II…………………………………………………………………………………… 9 LINKING RELIEF AND DEVELOPMENT……………………………………………………………. 11 MONITORING……………………………………………………………………………………… 11 STATEMENT OF HUMANITARIAN PRINCIPLES……………………………………………………. 13 SECTORS TO ADDRESS, AND OBJECTIVES, FOR JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000………………. 13 Table 5: Individual Project Activities by 15 Sector……………………………………………. Table 6: Individual Project Activities by Appealing -

(Etp) Species in West Africa

Issue Brief AN OVERVIEW OF THE ILLEGAL HARVEST OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES IN WEST AFRICA AQUATIC WILDMEAT: THE PLIGHT OF THREATENENED AQUATIC SPECIES Throughout West Africa, declining fisheries resources and rising human populations have accelerated the displacement WHAT IS AQUATIC BUSHMEAT? of many communities from their traditional food sources. This Aquatic wild meat, sometimes referred to in turn is driving new forms of aquatic meat consumption, as as aquatic bushmeat, is defined as the meat well as the rise of illegal local and international trade aimed at of aquatic species harvested and used by revenue generation. As a consequence, this aquatic harvest is humans as food resources, medicines and/ now seriously impacting large aquatic mammal, reptile and avian or cultural/ traditional items (e.g. religious biodiversity in the region. This aquatic harvest is ‘falling through items). Aquatic wildmeat includes marine the cracks’ between environment and fisheries Ministries, mammals such as manatees, cetaceans and agencies and international processes. hippopotamus, reptiles such as crocodiles and marine turtles, fish (sharks and rays), and In West Africa, as worldwide, aquatic species have been aquatic birds (herons, pelicans and storks harvested for decades by local populations. Some of the most amongst others). famous human uses are (1) the trade of the hawksbill marine turtle’ shell (bekko) through Japanese networks, (2) the consumption of manatee’s or marine turtle’s meat by coastal populations and (3) the harvest of sharks for their fins for the Asian market (Miliken & Tokunaga 1987; Groombridge & Luxmoore 1989; Diop & Dossa 2011). A WIDE VARIETY OF AQUATIC SPECIES ARE THREATENED Over time, aquatic bushmeat consumption, increasing human populations and poorly enforced measures punishing the use or trade of these aquatic species, could threaten the survival of many aquatic species. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Congo, Rep 2018 Human Rights Report

REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Republic of the Congo (ROC) is a presidential republic in which the constitution, promulgated in 2015, vests most decision-making authority and political power in the president and prime minister. In 2015 the Republic of the Congo adopted a new constitution, that extended previous maximum presidential term limits to three terms of five years, and provided complete immunity to former presidents. In April 2016 the Constitutional Court proclaimed the incumbent, Denis Sassou N’Guesso, winner of the March 2016 presidential election despite complaints of electoral irregularities. The government held the most recent legislative and local elections in July 2017. While the country has a multiparty political system, members of the president’s Congolese Labor Party (PCT) and its allies retained almost 90 percent of legislative seats, and PCT members occupied almost all senior government positions. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. During the year the country experienced significant positive changes regarding internal peace and security. In December 2017 the government and representatives of the Nsiloulou faction of the Ninja rebel militia group agreed to a ceasefire, thereby ending the conflict in the Pool region that had been ongoing since 2016. In June government and UN sources stated approximately 80-90 percent of the 161,000 persons displaced by the conflict had returned to their homes and villages. Human rights issues included reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings; forced disappearance; arbitrary detention by the government; harsh and life threatening prison conditions; political prisoners; infringement of citizens’ privacy rights; restrictions on freedoms of assembly and association; restrictions on the ability of citizens to change their government peacefully; corruption on the part of officials; violence against women, including rape, domestic violence, and child abuse; trafficking in persons; and child labor, including worst forms. -

West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA Bicc)

Christelle Dyc – PhD in biology an ecology, environmental Abidjan, 20th October 2017 pollution specialization West Africa Biodiversity and Climate Change (WA BiCC) SCOPING STUDY ON ADDRESSING ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES FOR CONSUMPTION AND TRADE DELIVERABLE N°6: FINAL SCOPING REPORT ON “ADDRESSING ILLEGAL HARVESTING OF AQUATIC ENDANGERED, THREATENED OR PROTECTED (ETP) SPECIES FOR CONSUMPTION, AND TRADE” Email: [email protected] Tel.: +225 44 02 19 17 (Côte d’Ivoire) / +32 495 496 007 (Belgium) Christelle Dyc – PhD in biology an ecology, environmental Abidjan, 20th October 2017 pollution specialization Table of content 1. Categorization of the issue ............................................................................................................................... 3 1.1. Chondrichthyans ....................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.1. sharks, rays excluded .......................................................................................................................... 3 a) Status ...................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1.2. Rays ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 a) Status ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Central African Republic

Central African Republic Introduction Key Economic Facts Risk Assessment (Provided by Coface) The Central African Republic is a landlocked country in Income Level (by per capita Low Income Country rating: D - A high-risk political and economic Central Africa that borders the countries of Cameroon, GNI): situation and an often very difficult business environment Chad, Sudan, South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of the Level of Development: Developing can have a very significant impact on corporate payment Congo, and the Republic of the Congo. GDP, PPP (current international $4.68 billion (2019) The geography of the Central African $): behavior. Corporate default probability is very high. Republic is vast and flat with scattered GDP growth (annual %): 2.97% (2019) Business Climate rating: E - The highest possible risk in hills in the northeast and southwest. The GDP per capita, PPP (current $986.68 (2019) terms of business climate. Due to a lack of available government system is a republic; the chief international $): financial information and an unpredictable legal system, of state is the president, and the head of government is the External debt stocks, total $880,204,018.40 (2019) doing business in this country is extremely difficult. prime minister. The Central African Republic has a (DOD, current US$): traditional economic system in which subsistence agriculture Manufacturing, value added (% 18.64% (2019) Strengths and forestry remain the of GDP): • Agricultural (cotton, coffee), forestry and mining backbone of the economy. The Current account balance (BoP, -$0.02 billion (1994) (diamond, gold, uranium) potential current US$): Central African Republic is a • Substantial international financial support member of the Economic Inflation, consumer prices 37.14% (2015) Weaknesses Community of Central African (annual %): States (ECCAS). -

Vol. 17: Republic of the Congo Sub-Saharan Report

Marubeni Research Institute 2016/09/02 Sub -Saharan Report Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the focal regions of Global Challenge 2015. These reports are by Mr. Kenshi Tsunemine, an expatriate employee working in Johannesburg with a view across the region. Vol. 17: Republic of the Congo December 15, 2015 I think most of you have heard something related to the acronym SAPE. This acronym is derived from the French expression, ”société des ambianceurs et des personnes élégantes”, or “the society of fashionable (ambience-makers) and elegant gentlemen” in English. In the Republic of the Congo it refers to the phenomenon of dressing in highly fashionable and luxury brand attire despite living in a country where the average income should not allow for the purchase of such high brand items, and has come to be known as the “Congo fashion style” (note 1). Picture 1: Making a film introducing SAPE photo Wikipedia So this time, it is the Republic of the Congo (Congo), a country that has gained attention for its fashionably dressed gentlemen (dandies) that I would like to introduce to you. Table 1: Congo Country Information The Republic of the Congo is located in the central part of the African continent with the Democratic Republic of the Congo on its southern and eastern borders, Cameroon in the north and Gabon bordering it in the west (note 2).To distinguish the Republic of the Congo from the neighboring Democratic Republic of the Congo, the Republic of the Congo is often referred to as Congo-Brazzaville, while the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) is called by its former name of “Zaire”. -

Health Action in Crises

RESOURCE MOBILIZATION FOR HEALTH ACTION IN CRISES CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC SAVING LIVES AND REDUCING SUFFERING HEALTH SITUATION Despite the increasing health crisis in Central African Republic (CAR), appeals for assistance have not been met and it remains an under- funded and “forgotten” emergency in one of the poorest country in the world. Health indicators have continued deteriorating rapidly in recent years as internal conflict has persisted causing widespread displacement and the destruction of the health infrastructure. An estimated 2.2 million people, over 60% of the population, have been affected by the conflict. The country is also host to over 50,000 refugees, mainly from neighbouring Sudan but also from Chad, the Democratic Republic of the Congo and another 19 African countries. Systems for disease surveillance and response and routine vaccination have broken down. Outbreaks of polio, meningitis and measles were reported in 2004/05. It is estimated that over one-third of the population is highly vulnerable to preventable diseases. In 2004, transmission of HIV, tuberculosis and sleeping sickness rose steeply. The situation is compounded by the lack of safe drinking water in rural areas, severe levels of childhood malnutrition and insufficient health services. The recent conflict has also seen an alarming increase in attacks of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV) against women. It has resulted in widespread trauma and a heightened risk of HIV/AIDS and other STIs. The population of CAR is facing a silent but pervasive health crisis. The situation is particularly desperate for the poorest segments of the population, for the most part women and children. -

ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 (VL for Attrid

ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 Data Definition Standard English Attribute Values ECCAIRS Aviation 1.3.0.12 VL for AttrID: 454 - Geographical areas Africa (Africa) 905 Algeria (Algeria) 5 People's Democratic Republic of Algeria Angola (Angola) 8 Republic of Angola Ascension Island (Ascension Island) 13 Ascension Island (Dependency of the UK overseas territory of Saint Helena) Benin (Benin) 26 Republic of Benin Botswana (Botswana) 30 Republic of Botswana Burkina Faso (Burkina Faso) 38 Burkina Faso Burundi (Burundi) 40 Republic of Burundi Cameroon (Cameroon) 42 Republic of Cameroon Canary Islands (Islas Canarias) (Canary Islands) 44 Autonomous community of the Canary Islands (Spanish archipelago) España (Islas Canarias) El Hierro (El Hierro) 1264 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Fuerteventura (Fuerteventura) 1273 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Gran Canaria (Gran Canaria) 1265 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias La Gomera (La Gomera) 1266 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias La Palma (La Palma) 1267 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Lanzarote (Lanzarote) 1274 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Tenerife (Tenerife) 1268 Comunidad Autónoma de Canarias Cape Verde (Cape Verde) 46 Republic of Cape Verde Central African Republic (Central African Republic) 49 Central African Republic Chad (Chad) 50 Republic of Chad Comoros (Comoros) 56 Union of the Comoros Congo (Congo) 57 Republic of the Congo. The Republic of the Congo is referred to as Congo-Brazzaville Congo, the Democratic Republic of (Congo, the Democratic Republic of) 309 Democratic Republic of the Congo. The Democratic