The River Congo – Africa's Sleeping Giant. Regional Integration And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regional Sources of Precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands Regionala Källor Till Nederbörden I Det Etiopiska Höglandet

Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2015: 2 Regional Sources of Precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands Regionala källor till nederbörden i det Etiopiska höglandet Elnaz Ashkriz DEPARTMENT OF EARTH SCIENCES INSTITUTIONEN FÖR GEOVETENSKAPER Independent Project at the Department of Earth Sciences Självständigt arbete vid Institutionen för geovetenskaper 2015: 2 Regional Sources of Precipitation in the Ethiopian Highlands Regionala källor till nederbörden i det Etiopiska höglandet Elnaz Ashkriz Copyright © Elnaz Ashkriz and the Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University Published at Department of Earth Sciences, Uppsala University (www.geo.uu.se), Uppsala, 2015 Sammanfattning Regionala källor till nederbörden i det Etiopiska höglandet Elnaz Ashkriz Denna uppsats undersöker ursprunget till den stora mängd nederbörd som faller i det etiopiska höglandet. Med Moisture transport into the Ethiopian Highlands av Ellen Viste och Asgeir Sorteberg (2011) som grund syftar denna uppsats till att jämföra samma data men genom att titta på ett mycket kortare intervall för att se vad som försummas när undersökningar på större skalor utförs. Medan undersökningen av Viste och Sorteberg (2011) fokuserar på de två regnrikaste månaderna, juli och augusti under elva år, 1998-2008, så fokuserar denna uppsats enbart på juli år 2008. Syftet med denna uppsats var att se vart nederbörden till det Etiopiska höglandet kommer ifrån under juli månad 2008. För att undersöka detta så har man valt att titta på parametrar såsom horisontell- och vertikal vindriktning på olika höjder samt fukt- innehållet i dessa vindar. Som grund för undersökningen så har denna uppsats, likt Vistes och Sortebergs, använt ERA-Interim data. -

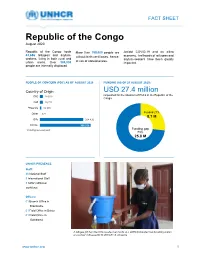

UNHCR Republic of Congo Fact Sheet

FACT SHEET Republic of the Congo August 2020 Republic of the Congo hosts More than 155,000 people are Amidst COVID-19 and an ailing 43,656 refugees and asylum- without birth certificates, hence, economy, livelihoods of refugees and seekers, living in both rural and asylum-seekers have been greatly at risk of statelessness. urban areas. Over 304,000 impacted. people are internally displaced PEOPLE OF CONCERN (POC) AS OF AUGUST 2020 FUNDING (AS OF 25 AUGUST 2020) Country of Origin USD 27.4 million requested for the situation of PoCs in the Republic of the DRC 20 810 Congo CAR 20,722 *Rwanda 10 565 Funded 27% Other 421 8.1 M IDPs 304 430 TOTAL: 356 926 * Including non-exempted Funding gap 73% 25.8 M UNHCR PRESENCE Staff: 46 National Staff 9 International Staff 8 IUNV (affiliated workforce) Offices: 01 Branch Office in Brazzaville 01 Field Office in Betou 01 Field Office in Gamboma A refugee girl from the DRC washes her hands at a UNHCR-installed handwashing station at a school in Brazzaville © UNHCR / S. Duysens www.unhcr.org 1 FACT SHEET > Republic of the Congo / August 2020 Working with Partners ■ Aligning with the Global Compact on Refugees (GCR), UNHCR in the Republic of the Congo (RoC) has diversified its partnership base to include five implementing partners, comprising local governmental and non-governmental organizations (NGOs), as well as international NGOs. ■ The National Committee for Assistance to Refugees (CNAR), is UNHCR’s main governmental partner, covering general refugee issues, particularly Refugee Status Determination (RSD). Other specific governmental partners include the Ministry of Social and Humanitarian Affairs (MASAH), the Ministries of Justice and Interior (for judicial issues and policies on issues related to statelessness and civil status registration), and the National Human Rights Commission (CNDH). -

Democratic Republic of Congo Constitution

THE CONSTITUTION OF THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO, 2005 [1] Table of Contents PREAMBLE TITLE I GENERAL PROVISIONS Chapter 1 The State and Sovereignty Chapter 2 Nationality TITLE II HUMAN RIGHTS, FUNDAMENTAL LIBERTIES AND THE DUTIES OF THE CITIZEN AND THE STATE Chapter 1 Civil and Political Rights Chapter 2 Economic, Social and Cultural Rights Chapter 3 Collective Rights Chapter 4 The Duties of the Citizen TITLE III THE ORGANIZATION AND THE EXERCISE OF POWER Chapter 1 The Institutions of the Republic TITLE IV THE PROVINCES Chapter 1 The Provincial Institutions Chapter 2 The Distribution of Competences Between the Central Authority and the Provinces Chapter 3 Customary Authority TITLE V THE ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COUNCIL TITLE VI DEMOCRACY-SUPPORTING INSTITUTIONS Chapter 1 The Independent National Electoral Commission Chapter 2 The High Council for Audiovisual Media and Communication TITLE VII INTERNATIONAL TREATIES AND AGREEMENTS TITLE VIII THE REVISION OF THE CONSTITUTION TITLE IX TRANSITORY AND FINAL PROVISIONS PREAMBLE We, the Congolese People, United by destiny and history around the noble ideas of liberty, fraternity, solidarity, justice, peace and work; Driven by our common will to build in the heart of Africa a State under the rule of law and a powerful and prosperous Nation based on a real political, economic, social and cultural democracy; Considering that injustice and its corollaries, impunity, nepotism, regionalism, tribalism, clan rule and patronage are, due to their manifold vices, at the origin of the general decline -

A Silent Crisis in Congo: the Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika

CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika Prepared by Geoffroy Groleau, Senior Technical Advisor, Governance Technical Unit The Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), with 920,000 new Bantus and Twas participating in a displacements related to conflict and violence in 2016, surpassed Syria as community 1 meeting held the country generating the largest new population movements. Those during March 2016 in Kabeke, located displacements were the result of enduring violence in North and South in Manono territory Kivu, but also of rapidly escalating conflicts in the Kasaï and Tanganyika in Tanganyika. The meeting was held provinces that continue unabated. In order to promote a better to nominate a Baraza (or peace understanding of the drivers of the silent and neglected crisis in DRC, this committee), a council of elders Conflict Spotlight focuses on the inter-ethnic conflict between the Bantu composed of seven and the Twa ethnic groups in Tanganyika. This conflict illustrates how representatives from each marginalization of the Twa minority group due to a combination of limited community. access to resources, exclusion from local decision-making and systematic Photo: Sonia Rolley/RFI discrimination, can result in large-scale violence and displacement. Moreover, this document provides actionable recommendations for conflict transformation and resolution. 1 http://www.internal-displacement.org/global-report/grid2017/pdfs/2017-GRID-DRC-spotlight.pdf From Harm To Home | Rescue.org CONFLICT SPOTLIGHT ⎯ A Silent Crisis in Congo: The Bantu and the Twa in Tanganyika 2 1. OVERVIEW Since mid-2016, inter-ethnic violence between the Bantu and the Twa ethnic groups has reached an acute phase, and is now affecting five of the six territories in a province of roughly 2.5 million people. -

Empty Forests, Empty Stomachs? Bushmeat and Livelihoods in the Congo and Amazon Basins

International Forestry Review Vol.13(3), 2011 355 Empty forests, empty stomachs? Bushmeat and livelihoods in the Congo and Amazon Basins R. NASI1, A. TABER1 and N. VAN VLIET2 1Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), Jalan CIFOR, Situ Gede, Sindang Barang, Bogor 16680, Indonesia 2Department of Geography and Geology, University of Copenhagen, Oster Voldgade 10, 1350 Copenhagen K, Denmark Email: [email protected], [email protected] and [email protected] SUMMARY Protein from forest wildlife is crucial to rural food security and livelihoods across the tropics. The harvest of animals such as tapir, duikers, deer, pigs, peccaries, primates and larger rodents, birds and reptiles provides benefits to local people worth millions of US$ annually and represents around 6 million tonnes of animals extracted yearly. Vulnerability to hunting varies, with some species sustaining populations in heavily hunted secondary habitats, while others require intact forests with minimal harvesting to maintain healthy populations. Some species or groups have been characterized as ecosystem engineers and ecological keystone species. They affect plant distribution and structure ecosystems, through seed dispersal and predation, grazing, browsing, rooting and other mechanisms. Global attention has been drawn to their loss through debates regarding bushmeat, the “empty forest” syndrome and their ecological importance. However, information on the harvest remains fragmentary, along with understanding of ecological, socioeconomic and cultural dimensions. Here we assess the consequences, both for ecosystems and local livelihoods, of the loss of these species in the Amazon and Congo basins. Keywords: bushmeat, livelihoods, forest, Amazon, Congo Forêts vides, estomacs vides? Viande de brousse et condition de vie dans les bassins du Congo et de l’Amazone. -

Why Is the African Economic Community Important? Mr

House Committee on Foreign Affairs Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, Global Human Rights, and International Organizations Hearing on “Will there be an African Economic Community?” January 9, 2014 Amadou Sy, Senior Fellow, Africa Growth Initiative, the Brookings Institution Chairman Smith, Ranking Member Bass, and Members of the Subcommittee, I would like to take this opportunity to thank you for convening this important hearing to discuss Africa’s progress towards establishing an economic community. I appreciate the invitation to share my views on behalf of the Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution. The Africa Growth Initiative at the Brookings Institution delivers high-quality research on issues of economic growth and development from an African perspective to better inform policy research. I have recently joined AGI from the International Monetary Fund’s where I led or participated in a number of missions to Africa over the past 15 years. Why is the African Economic Community Important? Mr. Chairman, before we start answering the main question, “Will there be an Africa Economic Community?” it is important to look at the reasons why a regionally integrated Africa is beneficial to African nations as well as the United States. In spite of its remarkable economic performance over the past decade, Africa needs to grow faster in order to transform its economy and create the resources needed to reduce poverty. Over the past 10 years, sub-Saharan Africa’s real GDP grew by 5.6 percent per year, a much faster rate than the world economy, which grew by 3.2 percent. At this rate of 5.6 percent, the region should double the size of its economy in about 13 years. -

A Lagrangian Perspective of the Hydrological Cycle in the Congo River Basin Rogert Sorí1, Raquel Nieto1,2, Sergio M

Earth Syst. Dynam. Discuss., doi:10.5194/esd-2017-21, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Earth Syst. Dynam. Discussion started: 9 March 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. A Lagrangian Perspective of the Hydrological Cycle in the Congo River Basin Rogert Sorí1, Raquel Nieto1,2, Sergio M. Vicente-Serrano3, Anita Drumond1, Luis Gimeno1 1 Environmental Physics Laboratory (EphysLab), Universidade de Vigo, Ourense, 32004, Spain 5 2 Department of Atmospheric Sciences, Institute of Astronomy, Geophysics and Atmospheric Sciences, University of SãoPaulo, São Paulo, 05508-090, Brazil 3 Instituto Pirenaico de Ecología, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas (IPE-CSIC), Zaragoza, 50059, Spain Correspondence to: Rogert Sorí ([email protected]) Abstract. 10 The Lagrangian model FLEXPART was used to identify the moisture sources of the Congo River Basin (CRB) and investigate their role in the hydrological cycle. This model allows us to track atmospheric parcels while calculating changes in the specific humidity through the budget of evaporation-minus-precipitation. The method permitted the identification at an annual scale of five continental and four oceanic regions that provide moisture to the CRB from both hemispheres over the course of the year. The most important is the CRB itself, providing more than 50% of the total atmospheric moisture income to the basin. Apart 15 from this, both the land extension to the east of the CRB together with the ocean located in the eastern equatorial South Atlantic Ocean are also very important sources, while the Red Sea source is merely important in the budget of (E-P) over the CRB, despite its high evaporation rate. -

Republic of the Congo

UNITED NATIONS CONSOLIDATED INTER-AGENCY APPEAL FOR THE REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000 November 1999 UNITED NATIONS For additional copies, please contact: UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs Complex Emergency Response Branch (CER-B) Palais des Nations 8-14 Avenue de la Paix CH - 1211 Geneva, Switzerland Tel.: (41 22) 917.1972 Fax: (41 22) 917.0368 E-Mail: [email protected] This document is also available on http://www.reliefweb.int/ iii iv TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY…………………………………………………………………………………………. 1 Table 1: Total Funding Requirement – By Sector and Appealing 2 Agency…………...… CONTEXT………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 Table 2: Effects of the Wars 1997 – 4 1999……..………………………………...………. 5 Table 3: ROC 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Urgan or Rural Origin… POLITICS, ECONOMY AND SECURITY……………………………………………………………. 5 Analysis, Scenarios and Response…….………………………………………………….. 7 A COMMON HUMANITARIAN ACTION PLAN (CHAP) TWO SCENARIOS………………………… 7 SCENARIO I……………………………………………………………………………………. 8 Table 4: 810,000 Displaced and Returned Persons by Place of Origin and Present Location……………………………………………………………………...…… 9 SCENARIO II…………………………………………………………………………………… 9 LINKING RELIEF AND DEVELOPMENT……………………………………………………………. 11 MONITORING……………………………………………………………………………………… 11 STATEMENT OF HUMANITARIAN PRINCIPLES……………………………………………………. 13 SECTORS TO ADDRESS, AND OBJECTIVES, FOR JANUARY – DECEMBER 2000………………. 13 Table 5: Individual Project Activities by 15 Sector……………………………………………. Table 6: Individual Project Activities by Appealing -

The Making of Concessions: Traditional Authorities, Transnational

The Making of Concessions: Traditional Authorities, Transnational Capital, and Territorialized Identities in Africa By Rebecca Hardin Paper presented to the Environmental Politics Seminar UC Berkeley, April 27 2007 Draft: please do not cite, nor reproduce Note: This paper presents a framework I am developing for a book project tentatively entitled “Concessionary Cultures.” I am currently revising the project for the University of California Press series “Colonialisms.” The opportunity to benefit from the EP seminar discussion is very welcome. In developing this to date I have incurred intellectual debts to the following readers: Arun Agrawal, Susan E. Cook, Jane Guyer, Alain Karsenty, Damani Partridge, John Galaty, Nahomi Ichino, Eduardo Kohn, Nadine Naber, Devra Meuller, Abena Osseo-Assare, Lorraine Paterson, Beth Povinelli, Hugh Raffles, Jesse Ribot, Mary Steedly, Miriam Ticktin, Diana Wylie,and an anonymous reviewer for the University of California Press. The research support of McGill University, the University of Michigan, and the Harvard Academy of International and Area Studies has been crucial, 1 Nestled within the Dzanga Sangha Dense Forest Reserve and Dzanga Ndoki National Park, the small town of Bayanga is the largest settlement in that southernmost triangle of the Central African Republic (CAR) that borders Cameroon and the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville). The establishment (1988) and subsequent legislation (1991) of the Park and Reserve (which I’ll refer to at the RDS) created one of the last protected areas established in the CAR, and one of only two sizeable forest reserves in that country. Conducting research on the role of tourism and trophy hunting in the management of this protected area found me sitting one evening with a pair of professional trophy hunters over the cocktails they call “sundowners.” During their hunts with clients that week, they complained, they had found abundant evidence of poaching, and they feared that too many of the animal trophies they sought might be marred by scars from wire snares. -

Country Coding Units

INSTITUTE Country Coding Units v11.1 - March 2021 Copyright © University of Gothenburg, V-Dem Institute All rights reserved Suggested citation: Coppedge, Michael, John Gerring, Carl Henrik Knutsen, Staffan I. Lindberg, Jan Teorell, and Lisa Gastaldi. 2021. ”V-Dem Country Coding Units v11.1” Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project. Funders: We are very grateful for our funders’ support over the years, which has made this ven- ture possible. To learn more about our funders, please visit: https://www.v-dem.net/en/about/ funders/ For questions: [email protected] 1 Contents Suggested citation: . .1 1 Notes 7 1.1 ”Country” . .7 2 Africa 9 2.1 Central Africa . .9 2.1.1 Cameroon (108) . .9 2.1.2 Central African Republic (71) . .9 2.1.3 Chad (109) . .9 2.1.4 Democratic Republic of the Congo (111) . .9 2.1.5 Equatorial Guinea (160) . .9 2.1.6 Gabon (116) . .9 2.1.7 Republic of the Congo (112) . 10 2.1.8 Sao Tome and Principe (196) . 10 2.2 East/Horn of Africa . 10 2.2.1 Burundi (69) . 10 2.2.2 Comoros (153) . 10 2.2.3 Djibouti (113) . 10 2.2.4 Eritrea (115) . 10 2.2.5 Ethiopia (38) . 10 2.2.6 Kenya (40) . 11 2.2.7 Malawi (87) . 11 2.2.8 Mauritius (180) . 11 2.2.9 Rwanda (129) . 11 2.2.10 Seychelles (199) . 11 2.2.11 Somalia (130) . 11 2.2.12 Somaliland (139) . 11 2.2.13 South Sudan (32) . 11 2.2.14 Sudan (33) . -

Congo, Rep 2018 Human Rights Report

REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO 2018 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Republic of the Congo (ROC) is a presidential republic in which the constitution, promulgated in 2015, vests most decision-making authority and political power in the president and prime minister. In 2015 the Republic of the Congo adopted a new constitution, that extended previous maximum presidential term limits to three terms of five years, and provided complete immunity to former presidents. In April 2016 the Constitutional Court proclaimed the incumbent, Denis Sassou N’Guesso, winner of the March 2016 presidential election despite complaints of electoral irregularities. The government held the most recent legislative and local elections in July 2017. While the country has a multiparty political system, members of the president’s Congolese Labor Party (PCT) and its allies retained almost 90 percent of legislative seats, and PCT members occupied almost all senior government positions. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces. During the year the country experienced significant positive changes regarding internal peace and security. In December 2017 the government and representatives of the Nsiloulou faction of the Ninja rebel militia group agreed to a ceasefire, thereby ending the conflict in the Pool region that had been ongoing since 2016. In June government and UN sources stated approximately 80-90 percent of the 161,000 persons displaced by the conflict had returned to their homes and villages. Human rights issues included reports of unlawful or arbitrary killings; forced disappearance; arbitrary detention by the government; harsh and life threatening prison conditions; political prisoners; infringement of citizens’ privacy rights; restrictions on freedoms of assembly and association; restrictions on the ability of citizens to change their government peacefully; corruption on the part of officials; violence against women, including rape, domestic violence, and child abuse; trafficking in persons; and child labor, including worst forms. -

Addressing Belgium's Crimes in the Congo Free State

Historical Security Council Addressing Belgium's crimes in the Congo Free State Director: Mauricio Quintero Obelink Moderator: Arantxa Marin Limón INTRODUCTION The Security Council is one of the six main organs of the United Nations. Its five principle purposes are to “maintain international peace and security, to develop diplomatic relations among nations, to cooperate in solving international problems, promote respect for human rights, and to be a centre for harmonizing the actions of nations” (What is the Security Council?, n.d.). The Committee is made up of 10 elected members and 5 permanent members (China, France, Russian Federation, United Kingdom, United States), all of which have veto power, which ultimately allows them to block proposed resolutions. As previously mentioned, the Security Council focuses on international matters regarding diplomatic relations, as well as the establishment of human rights protocols. For this reason, Belgium’s occupation of the greater Congo area is a topic of relevance within the committee. The Congo Free State was a large territory in Africa established by the Belgian Crown in 1885, and lasted until 1908. It was created after Leopold II commissioned European investors to explore and establish the land as European territory in order to gain international, economic; and political power. When the Belgian military gained power over the Congo territory, natives included, inhumane crimes were committed towards the inhabitants, all while under Leopold II’s supervision and approval. For this reason, King Leopold II’s actions, as well as the direct crimes committed by his army, must be held accountable in order to bring justice to the territory and its people.