African Squadron Reader 6Th Grade

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Armed Sloop Welcome Crew Training Manual

HMAS WELCOME ARMED SLOOP WELCOME CREW TRAINING MANUAL Discovery Center ~ Great Lakes 13268 S. West Bayshore Drive Traverse City, Michigan 49684 231-946-2647 [email protected] (c) Maritime Heritage Alliance 2011 1 1770's WELCOME History of the 1770's British Armed Sloop, WELCOME About mid 1700’s John Askin came over from Ireland to fight for the British in the American Colonies during the French and Indian War (in Europe known as the Seven Years War). When the war ended he had an opportunity to go back to Ireland, but stayed here and set up his own business. He and a partner formed a trading company that eventually went bankrupt and Askin spent over 10 years paying off his debt. He then formed a new company called the Southwest Fur Trading Company; his territory was from Montreal on the east to Minnesota on the west including all of the Northern Great Lakes. He had three boats built: Welcome, Felicity and Archange. Welcome is believed to be the first vessel he had constructed for his fur trade. Felicity and Archange were named after his daughter and wife. The origin of Welcome’s name is not known. He had two wives, a European wife in Detroit and an Indian wife up in the Straits. His wife in Detroit knew about the Indian wife and had accepted this and in turn she also made sure that all the children of his Indian wife received schooling. Felicity married a man by the name of Brush (Brush Street in Detroit is named after him). -

January Cover.Indd

Accessories 1:35 Scale SALE V3000S Masks For ICM kit. EUXT198 $16.95 $11.99 SALE L3H163 Masks For ICM kit. EUXT200 $16.95 $11.99 SALE Kfz.2 Radio Car Masks For ICM kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 5 - Tool Boxes Early German E-50 Flakpanzer Rheinmetall Geraet sWS with 20mm Flakvierling Detail Set EUXT201 $9.95 $7.99 AB35194 $17.99 $16.19 58 5.5cm Gun Barrels For Trumpter EU36195 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L100 $21.99 $19.79 SALE Merkava Mk.3D Masks For Meng kit. KV-1 and KV-2 - Vol. 4 - Tool Boxes Late Defender 110 Hardtop Detail Set HobbyBoss EUXT202 $14.95 $10.99 AB35195 $17.99 $16.19 Soviet 76.2mm M1936 (F22) Divisional Gun EU36200 $32.95 $29.66 SALE L 4500 Büssing NAG Window Mask KV-1 Vol. 6 - Lubricant Tanks Trumpeter KV-1 Barrel For Bronco kit. GMC Bofors 40mm Detail Set For HobbyBoss For ICM kit. AB35196 $14.99 $14.99 AB35L104 $9.99 EU36208 $29.95 $26.96 EUXT206 $10.95 $7.99 German Heavy Tank PzKpfw(r) KV-2 Vol-1 German Stu.Pz.IV Brumbar 15cm STuH 43 Gun Boxer MRAV Detail Set For HobbyBoss kit. Jagdpanzer 38(t) Hetzer Wheel mask For Basic Set For Trumpeter kit - TR00367. Barrel For Dragon kit. EU36215 $32.95 $29.66 AB35L110 $9.99 Academy kit. AB35212 $25.99 $23.39 Churchill Mk.VI Detail Set For AFV Club kit. EUXT208 $12.95 SALE German Super Heavy Tank E-100 Vol.1 Soviet 152.4mm ML-20S for SU-152 SP Gun EU36233 $26.95 $24.26 Simca 5 Staff Car Mask For Tamiya kit. -

International MARINE ACCIDENT REPORTING SCHEME

International MARINE ACCIDENT REPORTING SCHEME MARS REPORT No 160 February 2006 MARS 200604 Fall from Gangway 0220 Vessel all fast. Main shore gangway, which could 0900 Stations called fore and aft. Moorings tended and only be moved up-down vertically and not in a made tight as required. Duty officer on poop deck horizontal direction, nor could it be slewed in any for aft stations and Chief Officer on forward other direction, lowered to correct height. stations. No one was paying any particular Connecting gangway (sometimes referred to as attention near the gangway as it was located on an MOT gangway or formerly known as a brow) main deck and out of view from aft stations and was placed on the main gangway. The other end nobody was expected to visit the ship. of the brow was placed on the ship’s rails and 0918 Main engines tried out ahead/astern. made fast there. The ship’s safety net was used 0920 One person from the Seaman’s Club tried to board and a step ladder was made fast to ship’s railings the vessel, in spite of having been warned by the to facilitate the safe access onto the deck. Also a terminal operator (in his native language) against life buoy with a line was placed near the gangway. doing so, and caused the brow to over balance The gangway was manned at all times by a duty and he fell into the water along with the brow. A.B. The Cadet saw this happen from the forecastle deck and raised the alarm. -

Chapter 3 Ship Compartmentation and Watertight Integrity

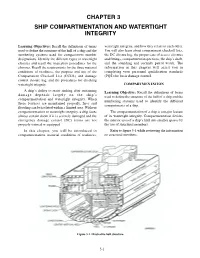

CHAPTER 3 SHIP COMPARTMENTATION AND WATERTIGHT INTEGRITY Learning Objectives: Recall the definitions of terms watertight integrity, and how they relate to each other. used to define the structure of the hull of a ship and the You will also learn about compartment checkoff lists, numbering systems used for compartment number the DC closure log, the proper care of access closures designations. Identify the different types of watertight and fittings, compartment inspections, the ship’s draft, closures and recall the inspection procedures for the and the sounding and security patrol watch. The closures. Recall the requirements for the three material information in this chapter will assist you in conditions of readiness, the purpose and use of the completing your personnel qualification standards Compartment Checkoff List (CCOL) and damage (PQS) for basic damage control. control closure log, and the procedures for checking watertight integrity. COMPARTMENTATION A ship’s ability to resist sinking after sustaining Learning Objective: Recall the definitions of terms damage depends largely on the ship’s used to define the structure of the hull of a ship and the compartmentation and watertight integrity. When numbering systems used to identify the different these features are maintained properly, fires and compartments of a ship. flooding can be isolated within a limited area. Without compartmentation or watertight integrity, a ship faces The compartmentation of a ship is a major feature almost certain doom if it is severely damaged and the of its watertight integrity. Compartmentation divides emergency damage control (DC) teams are not the interior area of a ship’s hull into smaller spaces by properly trained or equipped. -

Sailing Trans-Atlantic on the USCG Barque Eagle

PassageRite of Sailing Trans-Atlantic On The USCG Barque Eagle odern life is complicated. I needed a car, a bus, a train and a taxi to get to my square-rigger. When no cabs could be had, a young police officer offered me a lift. Musing on my last conveyance in such a vehicle, I thought, My, how a touch of gray can change your circumstances. It was May 6, and I had come to New London, Connecticut, to join the Coast Guard training barque Eagle to sail her to Dublin, Ireland. A snotty, wet Measterly met me at the pier, speaking more of March than May. The spires of New Lon- don and the I-95 bridge jutted from the murk, and a portion of a nuclear submarine was discernible across the Thames River at General Dynamics Electric Boat. It was a day for sitting beside a wood stove, not for going to sea, but here I was, and somehow it seemed altogether fitting for going aboard a sailing ship. The next morning was organized chaos. Cadets lugged sea bags aboard. Human chains passed stores across the gangway and down into the deepest recesses of the ship. Station bills were posted and duties disseminated. I met my shipmates in passing and in passageways. Boatswain Aaron Stapleton instructed me in the use of a climbing harness and then escorted me — and the mayor of New London — up the foremast. By completing this evolution, I was qualified in the future to work aloft. Once stowed for sea, all hands mustered amidships. -

December 2007 Crew Journal of the Barque James Craig

December 2007 Crew journal of the barque James Craig Full & By December 2007 Full & By The crew journal of the barque James Craig http://www.australianheritagefleet.com.au/JCraig/JCraig.html Compiled by Peter Davey [email protected] Production and photos by John Spiers All crew and others associated with the James Craig are very welcome to submit material. The opinions expressed in this journal may not necessarily be the viewpoint of the Sydney Maritime Museum, the Sydney Heritage Fleet or the crew of the James Craig or its officers. 2 December 2007 Full & By APEC parade of sail - Windeward Bound, New Endeavour, James Craig, Endeavour replica, One and All Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 December 2007 Full & By Full & By December 2007 7 Radio procedures on James Craig adio procedures being used onboard discomfort. Effective communication Rare from professional to appalling relies on message being concise and clear. - mostly on the appalling side. The radio Consider carefully what is to be said before intercoms are not mobile phones. beginning to transmit. Other operators may The ship, and the ship’s company are be waiting to use the network. judged by our appearance and our radio procedures. Remember you may have Some standard words and phases. to justify your transmission to a marine Affirm - Yes, or correct, or that is cor- court of inquiry. All radio transmissions rect. or I agree on VHF Port working frequencies are Negative - No, or this is incorrect or monitored and tape recorded by the Port Permission not granted. -

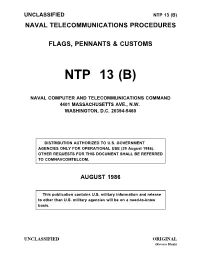

NTP 13 (B): Flags, Pennants, & Customs

UNCLASSIFIED NTP 13 (B) NAVAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS PROCEDURES FLAGS, PENNANTS & CUSTOMS NTP 13 (B) NAVAL COMPUTER AND TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMAND 4401 MASSACHUSETTS AVE., N.W. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20394-5460 DISTRIBUTION AUTHORIZED TO U.S. GOVERNMENT AGENCIES ONLY FOR OPERATIONAL USE (29 August 1986). OTHER REQUESTS FOR THIS DOCUMENT SHALL BE REFERRED TO COMNAVCOMTELCOM. AUGUST 1986 This publication contains U.S. military information and release to other than U.S. military agencies will be on a need-to-know basis. UNCLASSIFIED ORIGINAL (Reverse Blank) NTP-13(B) DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY NAVAL TELECOMMUNICATIONS COMMAND 440l MASSACHUSETTS AVENUE, N.W. WASHINGTON, D.C. 20394-5460 15 September 1986 LETTER OF PROMULGATION 1. NTP 13(B), FLAGS, PENNANTS AND CUSTOMS, was developed under the direction of the Commander, Naval Telecommunications Command, and is promulgated for use by the U.S. Navy and Coast Guard. 2. NTP 13(B) is an unclassified, non-registered publication. 3. NTP 13(B) is EFFECTIVE UPON RECEIPT and supersedes NTP 13(A). 4. Permission is granted to copy or make extracts from this publication without the consent of the Commander, Naval Telecommunications Command. 5. This publication, or extracts thereof, may be carried in aircraft for use therein. 6. Correspondence concerning this publication should be addressed via the normal military chain of command to the Commander, Naval Telecommunications Command (32), 4401 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W., Washington, D.C. 20394-5460. 7. This publication has been reviewed and approved in accordance with SECNAV Instruction 5600.16. A. F. CAMPBELL Rear Admiral, U.S. Navy Commander, Naval Telecommunications Command ORIGINAL ii NTP-13(B) RECORD OF CHANGES AND CORRECTIONS Enter Change or Correction in Appropriate Column Identification of Change or Correction; Reg. -

Operation Dominic I

OPERATION DOMINIC I United States Atmospheric Nuclear Weapons Tests Nuclear Test Personnel Review Prepared by the Defense Nuclear Agency as Executive Agency for the Department of Defense HRE- 0 4 3 6 . .% I.., -., 5. ooument. Tbe t k oorreotsd oontraofor that tad oa the book aw ra-ready c I I i I 1 1 I 1 I 1 i I I i I I I i i t I REPORT NUMBER 2. GOVT ACCESSION NC I NA6OccOF 1 i Technical Report 7. AUTHOR(.) i L. Berkhouse, S.E. Davis, F.R. Gladeck, J.H. Hallowell, C.B. Jones, E.J. Martin, DNAOO1-79-C-0472 R.A. Miller, F.W. McMullan, M.J. Osborne I I 9. PERFORMING ORGAMIIATION NWE AN0 AODRCSS ID. PROGRAM ELEMENT PROJECT. TASU Kamn Tempo AREA & WOW UNIT'NUMSERS P.O. Drawer (816 State St.) QQ . Subtask U99QAXMK506-09 ; Santa Barbara, CA 93102 11. CONTROLLING OFClCC MAME AM0 ADDRESS 12. REPORT DATE 1 nirpctor- . - - - Defense Nuclear Agency Washington, DC 20305 71, MONITORING AGENCY NAME AODRCSs(rfdIfI*mI ka CamlIlIU Olllc.) IS. SECURITY CLASS. (-1 ah -*) J Unclassified SCHCDULC 1 i 1 I 1 IO. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES This work was sponsored by the Defense Nuclear Agency under RDT&E RMSS 1 Code 6350079464 U99QAXMK506-09 H2590D. For sale by the National Technical Information Service, Springfield, VA 22161 19. KEY WOROS (Cmlmm a nm.. mid. I1 n.c...-7 .nd Id.nllh 4 bled nlrmk) I Nuclear Testing Polaris KINGFISH Nuclear Test Personnel Review (NTPR) FISHBOWL TIGHTROPE DOMINIC Phase I Christmas Island CHECKMATE 1 Johnston Island STARFISH SWORDFISH ASROC BLUEGILL (Continued) D. -

The Battle of Midway

OVERVIEW ESSAY: The Battle of Midway (Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 73065.) One of Japan’s main goals during World War II was to THE BATTLE remove the United States as a Pacific power in order Early on the morning of June 4, aircraft from four to gain territory in east Asia and the southwest Pacific Japanese aircraft carriers attacked and severely islands. Japan hoped to defeat the US Pacific Fleet and damaged the US base on Midway. Unbeknownst to the use Midway as a base to attack Pearl Harbor, securing Japanese, the US carrier forces were just to the east of dominance in the region and then forcing a negotiated the island and ready for battle. After their initial attacks, peace. the Japanese aircraft headed back to their carriers to BREAKING THE CODE rearm and refuel. While the aircraft were returning, the Japanese navy became aware of the presence of US The United States was aware that the Japanese naval forces in the area. were planning an attack in the Pacific (on a TBD Devastator torpedo-bombers and SBD Dauntless location the Japanese code-named “AF”) because dive-bombers from the USS Enterprise, USS Hornet, Navy cryptanalysts had begun breaking Japanese and USS Yorktown attacked the Japanese fleet. The communication codes in early 1942. The attack location Japanese carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu were hit, and time were confirmed when the American base at set ablaze, and abandoned. Hiryu, the only surviving Midway sent out a false message that it was short of Japanese carrier, responded with two waves of fresh water. -

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress

Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress September 16, 2021 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RL32665 Navy Force Structure and Shipbuilding Plans: Background and Issues for Congress Summary The current and planned size and composition of the Navy, the annual rate of Navy ship procurement, the prospective affordability of the Navy’s shipbuilding plans, and the capacity of the U.S. shipbuilding industry to execute the Navy’s shipbuilding plans have been oversight matters for the congressional defense committees for many years. In December 2016, the Navy released a force-structure goal that calls for achieving and maintaining a fleet of 355 ships of certain types and numbers. The 355-ship goal was made U.S. policy by Section 1025 of the FY2018 National Defense Authorization Act (H.R. 2810/P.L. 115- 91 of December 12, 2017). The Navy and the Department of Defense (DOD) have been working since 2019 to develop a successor for the 355-ship force-level goal. The new goal is expected to introduce a new, more distributed fleet architecture featuring a smaller proportion of larger ships, a larger proportion of smaller ships, and a new third tier of large unmanned vehicles (UVs). On June 17, 2021, the Navy released a long-range Navy shipbuilding document that presents the Biden Administration’s emerging successor to the 355-ship force-level goal. The document calls for a Navy with a more distributed fleet architecture, including 321 to 372 manned ships and 77 to 140 large UVs. A September 2021 Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report estimates that the fleet envisioned in the document would cost an average of between $25.3 billion and $32.7 billion per year in constant FY2021 dollars to procure. -

Aircraft Collection

A, AIR & SPA ID SE CE MU REP SEU INT M AIRCRAFT COLLECTION From the Avenger torpedo bomber, a stalwart from Intrepid’s World War II service, to the A-12, the spy plane from the Cold War, this collection reflects some of the GREATEST ACHIEVEMENTS IN MILITARY AVIATION. Photo: Liam Marshall TABLE OF CONTENTS Bombers / Attack Fighters Multirole Helicopters Reconnaissance / Surveillance Trainers OV-101 Enterprise Concorde Aircraft Restoration Hangar Photo: Liam Marshall BOMBERS/ATTACK The basic mission of the aircraft carrier is to project the U.S. Navy’s military strength far beyond our shores. These warships are primarily deployed to deter aggression and protect American strategic interests. Should deterrence fail, the carrier’s bombers and attack aircraft engage in vital operations to support other forces. The collection includes the 1940-designed Grumman TBM Avenger of World War II. Also on display is the Douglas A-1 Skyraider, a true workhorse of the 1950s and ‘60s, as well as the Douglas A-4 Skyhawk and Grumman A-6 Intruder, stalwarts of the Vietnam War. Photo: Collection of the Intrepid Sea, Air & Space Museum GRUMMAN / EASTERNGRUMMAN AIRCRAFT AVENGER TBM-3E GRUMMAN/EASTERN AIRCRAFT TBM-3E AVENGER TORPEDO BOMBER First flown in 1941 and introduced operationally in June 1942, the Avenger became the U.S. Navy’s standard torpedo bomber throughout World War II, with more than 9,836 constructed. Originally built as the TBF by Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, they were affectionately nicknamed “Turkeys” for their somewhat ungainly appearance. Bomber Torpedo In 1943 Grumman was tasked to build the F6F Hellcat fighter for the Navy. -

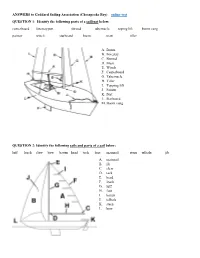

ANSWERS to Goddard Sailing Association

ANSWERS to Goddard Sailing Association (Chesapeake Bay) online-test QUESTION 1: Identify the following parts of a sailboat below: centerboard forestay port shroud tabernacle toping lift boom vang painter winch starboard boom mast tiller A. Boom B. Forestay C. Shroud D. Mast E. Winch F. Centerboard G. Tabernacle H. Tiller I. Topping lift J. Painter K. Port L. Starboard M. Boom vang QUESTION 2: Identify the following sails and parts of a sail below: luff leach clew bow batten head tack foot mainsail stern telltale jib A. mainsail B. jib C. clew D. tack E. head F. leach G. luff H. foot I. batten J. telltale K. stern L. bow QUESTION 3: Match the following items found on a sailboat with one of the functions listed below. mainsheet jibsheet(s) halyard(s) fairlead rudder winch cleat tiller A. Used to raise (hoist) the sails HALYARD B. Fitting used to tie off a line CLEAT C. Furthest forward on-deck fitting through which the jib sheet passes FAIRLEAD D. Controls the trim of the mainsail MAINSHEET E. Controls the angle of the rudder TILLER F. A device that provides mechanical advantage WINCH G. Controls the trim of the jib JIBSHEET H. The fin at the stern of the boat used for steering RUDDER QUESTION 4: Match the following items found on a sailboat with one of the functions listed below. stays shrouds telltales painter sheets boomvang boom topping lift outhaul downhaul/cunningham A. Lines for adjusting sail positions SHEETS B. Used to adjust the tension in the luff of the mainsail DOWNHAUL/CUNNINGHAM C.