The Way of the Sea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sailing Trans-Atlantic on the USCG Barque Eagle

PassageRite of Sailing Trans-Atlantic On The USCG Barque Eagle odern life is complicated. I needed a car, a bus, a train and a taxi to get to my square-rigger. When no cabs could be had, a young police officer offered me a lift. Musing on my last conveyance in such a vehicle, I thought, My, how a touch of gray can change your circumstances. It was May 6, and I had come to New London, Connecticut, to join the Coast Guard training barque Eagle to sail her to Dublin, Ireland. A snotty, wet Measterly met me at the pier, speaking more of March than May. The spires of New Lon- don and the I-95 bridge jutted from the murk, and a portion of a nuclear submarine was discernible across the Thames River at General Dynamics Electric Boat. It was a day for sitting beside a wood stove, not for going to sea, but here I was, and somehow it seemed altogether fitting for going aboard a sailing ship. The next morning was organized chaos. Cadets lugged sea bags aboard. Human chains passed stores across the gangway and down into the deepest recesses of the ship. Station bills were posted and duties disseminated. I met my shipmates in passing and in passageways. Boatswain Aaron Stapleton instructed me in the use of a climbing harness and then escorted me — and the mayor of New London — up the foremast. By completing this evolution, I was qualified in the future to work aloft. Once stowed for sea, all hands mustered amidships. -

Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction

In the Wake of Conrad: Ships and Sailors in Early Twentieth-Century Maritime Fiction Alexandra Caroline Phillips BA (Hons) Cardiff University, MA King’s College, London A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Cardiff University 30 March 2015 1 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 4 Introduction - Contexts and Tradition 5 The Transition from Sail to Steam 6 The Maritime Fiction Tradition 12 The Changing Nature of the Sea Story in the Twentieth Century 19 PART ONE Chapter 1 - Re-Reading Conrad and Maritime Fiction: A Critical Review 23 The Early Critical Reception of Conrad’s Maritime Texts 24 Achievement and Decline: Re-evaluations of Conrad 28 Seaman and Author: Psychological and Biographical Approaches 30 Maritime Author / Political Novelist 37 New Readings of Conrad and the Maritime Fiction Tradition 41 Chapter 2 - Sail Versus Steam in the Novels of Joseph Conrad Introduction: Assessing Conrad in the Era of Steam 51 Seamanship and the Sailing Ship: The Nigger of the ‘Narcissus’ 54 Lord Jim, Steam Power, and the Lost Art of Seamanship 63 Chance: The Captain’s Wife and the Crisis in Sail 73 Looking back from Steam to Sail in The Shadow-Line 82 Romance: The Joseph Conrad / Ford Madox Ford Collaboration 90 2 PART TWO Chapter 3 - A Return to the Past: Maritime Adventures and Pirate Tales Introduction: The Making of Myths 101 The Seduction of Silver: Defoe, Stevenson and the Tradition of Pirate Adventures 102 Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and the Tales of Captain Sharkey 111 Pirates and Petticoats in F. Tennyson Jesse’s -

Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf

OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management Gulf of Mexico OCS Region OCS Study BOEM 2012-008 Inventory and Analysis of Archaeological Site Occurrence on the Atlantic Outer Continental Shelf Author TRC Environmental Corporation Prepared under BOEM Contract M08PD00024 by TRC Environmental Corporation 4155 Shackleford Road Suite 225 Norcross, Georgia 30093 Published by U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Ocean Energy Management New Orleans Gulf of Mexico OCS Region May 2012 DISCLAIMER This report was prepared under contract between the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and TRC Environmental Corporation. This report has been technically reviewed by BOEM, and it has been approved for publication. Approval does not signify that the contents necessarily reflect the views and policies of BOEM, nor does mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endoresements or recommendation for use. It is, however, exempt from review and compliance with BOEM editorial standards. REPORT AVAILABILITY This report is available only in compact disc format from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Gulf of Mexico OCS Region, at a charge of $15.00, by referencing OCS Study BOEM 2012-008. The report may be downloaded from the BOEM website through the Environmental Studies Program Information System (ESPIS). You will be able to obtain this report also from the National Technical Information Service in the near future. Here are the addresses. You may also inspect copies at selected Federal Depository Libraries. U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. -

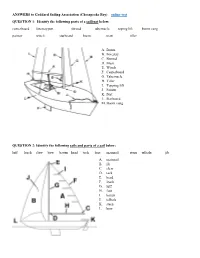

ANSWERS to Goddard Sailing Association

ANSWERS to Goddard Sailing Association (Chesapeake Bay) online-test QUESTION 1: Identify the following parts of a sailboat below: centerboard forestay port shroud tabernacle toping lift boom vang painter winch starboard boom mast tiller A. Boom B. Forestay C. Shroud D. Mast E. Winch F. Centerboard G. Tabernacle H. Tiller I. Topping lift J. Painter K. Port L. Starboard M. Boom vang QUESTION 2: Identify the following sails and parts of a sail below: luff leach clew bow batten head tack foot mainsail stern telltale jib A. mainsail B. jib C. clew D. tack E. head F. leach G. luff H. foot I. batten J. telltale K. stern L. bow QUESTION 3: Match the following items found on a sailboat with one of the functions listed below. mainsheet jibsheet(s) halyard(s) fairlead rudder winch cleat tiller A. Used to raise (hoist) the sails HALYARD B. Fitting used to tie off a line CLEAT C. Furthest forward on-deck fitting through which the jib sheet passes FAIRLEAD D. Controls the trim of the mainsail MAINSHEET E. Controls the angle of the rudder TILLER F. A device that provides mechanical advantage WINCH G. Controls the trim of the jib JIBSHEET H. The fin at the stern of the boat used for steering RUDDER QUESTION 4: Match the following items found on a sailboat with one of the functions listed below. stays shrouds telltales painter sheets boomvang boom topping lift outhaul downhaul/cunningham A. Lines for adjusting sail positions SHEETS B. Used to adjust the tension in the luff of the mainsail DOWNHAUL/CUNNINGHAM C. -

Sailing Course Materials Overview

SAILING COURSE MATERIALS OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION The NCSC has an unusual ownership arrangement -- almost unique in the USA. You sail a boat jointly owned by all members of the club. The club thus has an interest in how you sail. We don't want you to crack up our boats. The club is also concerned about your safety. We have a good reputation as competent, safe sailors. We don't want you to spoil that record. Before we started this training course we had many incidents. Some examples: Ran aground in New Jersey. Stuck in the mud. Another grounding; broke the tiller. Two boats collided under the bridge. One demasted. Boats often stalled in foul current, and had to be towed in. Since we started the course the number of incidents has been significantly reduced. SAILING COURSE ARRANGEMENT This is only an elementary course in sailing. There is much to learn. We give you enough so that you can sail safely near New Castle. Sailing instruction is also provided during the sailing season on Saturdays and Sundays without appointment and in the week by appointment. This instruction is done by skippers who have agreed to be available at these times to instruct any unkeyed member who desires instruction. CHECK-OUT PROCEDURE When you "check-out" we give you a key to the sail house, and you are then free to sail at any time. No reservation is needed. But you must know how to sail before you get that key. We start with a written examination, open book, that you take at home. -

Maryland Historical Trust 2 Location 3 Classification 5

Survey No. T503 Magi No. Maryland Historical Trust 2105035633 State Historic Sites Inventory Form DOE Yes x no CHESAPEAKE BAY SAILING LOG CANOE FLEET THtATIC GROUP /- /r — I Name (indicate preferred name) historic isi_issot and/or common 1og canoe 2 Location street & number Miles River Yacht Club n/a_ not for pubikatlon - city, town St. Michacis vicinity of congressional district First 041 state Maryland 024 county Talbot 3 Classification Category Ownership Satus Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum building(s) private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in progress -- educational private re&dence site Public Acquisition Accessible ac._ entertainment religious _L object in process _2_ yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial _J transportation not applicable no _rnilitary other: 4 Owner of Property (give names and mailing addresses of all owners) name John C. North street & number P.Q. Box 479 telephone no. 8226378 city, town Easton state and zip code Maryland 21601 5 Location_of_Legal_Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. n/a liber street & number folio city, town state 6 Representation in Existing Historical Surveys title Maryland Historical Trust Historic Sites inventory X dat e 1984 federal state county be 21 State Circle depository for survey records Annapolis city, town Maryland 21401 ____- state 7 Description Survey No. T-503 Condlton Check one CIeck on e _2 excellent - deteriorated unaltered Y..origInal site good ruins .L_ altered moved date of move fair unexposed Prepare both a surumary,paragraph and a general description of the resource and its various element as it exists today. ISLAND BLOSSOM is a 32' 7-1/2' sailing log canoe built in 1892 in Tilghtnan, Maryland by William Sidney Covington. -

Finishing the Fore Deck Fittings... Inside of the Opposite Cap Rail

Anchor davit Winch bits Finishing the Fore Deck Fittings... inside of the opposite cap rail. This bracket can be seen in the photo above. They will be painted black. There are only a few fittings that need to be completed before we move ahead to the next phase of this project. The winch bits are supplied as a casted piece which That will be the creation of the masts and bowsprit and finally needs to be painted. I decided to paint the bits to match the rigging of the Phantom. Start by fabricating the anchor the color of the stained wood used throughout the model. davit out of 22 gauge black wire. Simply bend the wire to It was sanded and filed first to clean it up. The elements conform to the shape of the davit as it is shown on the plans. of the winch itself were painted black. Handles were A small bead or drop of super glue was placed on the tip of added as shown on the plans. They were shaped out of the davit and allowed to dry. It formed a nice round bead 28 gauge black wire and glued into pre-drilled holes on when dry which after being painted black, finishes it off very the sides of each winch drum. The entire assembly was nicely. glued onto the deck in its proper location as taken from the plans. The bowsprit will seat into these bits as you The davit is glued into a hole that was pre-drilled in the prop- can see in the photo above. -

Swan 45 Tuning Guide Solutions for Today’S Sailors 2

1 Swan 45 TUNE YOUR RIG FOR OUTRIGHT SPEED Swan 45 Tuning Guide Solutions for today’s sailors 2 We hope you enjoy your Swan 45 Tuning Guide. North class Swan 45 representatives and personnel have invested a lot of time to make this guide as helpful as possible for you. Tuning and trim advice offered here have been proven over time with top results in the class. North has become the world leader in sailmaking through an ongoing commitment to making sails faster, lighter and longer lasting. We are equally committed to working as a team with our customers. As always, if you have any questions or comments we would love to hear from you. Please contact your Offshore One Design class representative. Sincerely, Ken Read President North Sails Group Contents Recommended Inventory Pg. 1 Setting Up at the Spar Mainsail Pg. 3 Target Speeds and Angles All Purpose MNi-4 Mainsail 3Di 780iM RAW 19600 Pg. 4 Jib Trim Headsails Pg. 6 Mainsail Trim Li-3 Headsail 0-10kts 3Di – 780iM RAW 14700 Mi-3 Headsail 3Di – 780iM RAW 16800 Pg. 8 Spinnaker Trim Hi-3 Headsail 3Di – 780iM RAW 22400 HWJi-2 Headsail 3D – 780i 23800 Pg. 10 Spinnaker Trim Key Points Pg. 11 Hot Tips Downwind Sails A1-3 SuperLite – SL50 A2-3 SuperKote – SK60 A3-1 SuperKote – SK130 SD S2-4 SuperKote – SK60 S4-3 SuperKote – SK90 Swan 45 Tuning Guide Solutions for today’s sailors 1 1.25m White Band Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Fig. 3 Fig. 1 Fig. 2 Setting Up at the Spar Step 5 Step 1 Using the centerline headsail halyard, Step carbon spar onto adjustable swing the halyard to the TuffLuff headstay mast step. -

Colligo Marine® Lashing Tie Off Instructions

Colligo Marine® Lashing Tie off instructions This image shows a nicely finished off lashing using our CSS71 Line Terminator and CSS61 Chainplate Distributor using 5 mm or 3/16” Dyneema line. You can see the critical hourglass shape that gets tighter as the shroud tension gets tighter. It is very secure but is also allows for easy unlashing. Without the hourglass shape you would need to place the knot at the bottom of the lashing which makes it very painful to lash and unlash. There is a series of individual half hitches that form the attractive spiral configuration of the lashing. This also creates redundant security ensuring that your lashing will not shake out. Tensioning Prior to lashing off please tension the shroud or stay to the desired tension. Tensioning can be achieved in several ways: 1. The best method is to take your boat sailing and adjust the leeward shroud, letting the wind blow the rig to leeward and do the work for you. Tack back and forth in low to moderate winds and keep adjusting the leeward shrouds. Always keep the mast straight and in column. In the end, you want your leeward shrouds to just come loose at your wind reef point, usually about 15-20 knots of wind speed. 2. You can also bring a halyard down and tie it off to your lashing line and use a winch for tensioning. This method will probably mean that you would need to help the lashing line thru all the holes in the line terminators and distributors while at the same time adding tension with the winch. -

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails the Perception of Risk Is Very Important, Even Essential, to Organization the Sense of Adventure and the Success of Our Program

Setting, Dousing and Furling Sails The perception of risk is very important, even essential, to Organization the sense of adventure and the success of our program. The When at sea the organization for setting and assurance of safety is essential dousing sails will be determined by the Captain to the survival of our program and the First Mate. With a large and well- and organization. The trained crew, the crew may be able to be broken balancing of these seemingly into two groups, one for the foremast and one conflicting needs is one of the for the mainmast. With small crews, it will most difficult and demanding become necessary for everyone to know and tasks you will have in working work all of the lines anywhere on the ship. In with this program. any event, particularly if watches are being set, it becomes imperative that everyone have a good understanding of all lines and maneuvers the ship may be asked to perform. Safety Sailing the brigantines safely is our primary goal and the Los Angeles Maritime Institute has an enviable safety record. We should stress, however, that these ships are NOT rides at Disneyland. These are large and powerful sailing vessels and you can be injured, or even killed, if proper procedures are not followed in a safe, orderly, and controlled fashion. As a crewmember you have as much responsibility for the safe running of these vessels as any member of the crew, including the ship’s officers. 1. When laying aloft, crewmembers should always climb and descend on the weather side of the shrouds and the bowsprit. -

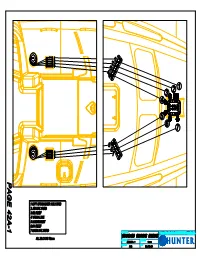

HUNTER 38 FURL STANDING RIGGING ITEM QTY WIRE SIZE FITTINGS OVERALL LENGTH 1 D3 2 5/16" 8 Mm T-TERMINAL 308-326 15Ft

HUNTER 38 CONVENTIONAL RUNNING RIGGING SPECIFICATIONS Selden Mast #: RRIG-0056S OPT/STD ITEM QTY Line Size Line Type Color End 1 Length End 2 1 STD MAIN HALYARD 1 12mm (1/2") 32/3 pl BLUE 307-047 SHACKLE /KNOT 39 m 128 ft BARE 2 STD JIB HALYARD 1 12mm (1/2") 32/3 pl RED 307-021 SHACKLE /KNOT 37 m 121 ft BARE 3 STD MAIN TRAVELER LINE 2 10mm (5/16") 16/16 pl WHITE SMALL EYE 7.9 m 26 ft BARE 4 STD MAINSHEET 1 12mm (1/2") 16/16 pl BLUE SMALL EYE 26 m 85 ft BARE 5 STD REEFING LINE #1 1 12mm (1/2") 16/16 pl GREEN BARE 25.9 m 85 ft BARE 6 STD REEFING LINE #2 1 12mm (1/2") 16/16 pl RED BARE 33.5 m 110 ft BARE 7 STD JIB SHEET 2 12mm (1/2") 16/16 pl RED BARE 14.5 m 48 ft BARE 8 OPT CRUISING SPINN. SHEET 2 10mm (3/8") 32/3 pl WHITE BARE 24 m 79 ft BARE 9 OPT SPINNAKER HALYARD 1 12mm (1/2") 16/16 pl RED 307-338 SHACKLE /KNOT 36 m 121ft BARE 10 OPT RODKICKER TACKLE 1 12mm (1/2") 16/16 pl WHITE SMALL EYE 9 m 30 ft BARE PLASTIC 307-015 SHACKLE Thimble Block 11 STD LAZY JACK WIRE 2 4 MM (5/32) WHITE 5.5 m 18 ft COATED 7X7 12 STD FIXED LAZY JACK LINE 2 10mm (3/8) 16/16 pl WHITE BARE 6 m 20 ft. -

1998 Lake Michigan Crew Over Board Study Provided by the Lake Michigan Sail Racing Federation (LMSRF)

1998 Lake Michigan Crew Over Board Study Provided by the Lake Michigan Sail Racing Federation (LMSRF) This is an effort to encompass Offshore Racing Sailing stories from crew over boards during racing, on the way in or to the race course, delivery trips before or after a race along with Lake Michigan boats that attend races away from Lake Michigan. As these stories developed, it became clear that when a boat sank, the entire crew was then "over board". This simple fact, originally not considered, added greatly to the database. Many stories contain just the cold hard facts. The emotions and anxieties were removed to keep the possibility of a libel suit to a minimum, since these are stories typically told of others on board. The range of emotions in the stories include shrieking of women who believe they are seeing someone drown, foul language amongst crew accusing others of not pulling their weight, accusations that certain people are short of brain power or just plain stupid. Some involve crew mad at skipper, skipper mad at crew and crew mad at crew. Much of this type of anger seems to come out just at the stressful time of recovery and diffused quickly thereafter. Put yourself on board in each story and imagine how you would react in the situation. LM Case 1 As reported by Alan R. Johnston, January 21, 1998 In the 1973 Chicago-Mackinac race off Point Betsie, MI at 5 to 6 AM with the sun just over the horizon making light, there was a thud on the deck.