Palmyra: an Assessment of Virtual and Physical Reconstruction Techniques and Their Ethical Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Monuments of Terrorism: (De)Selecting Memory and Symbolic Exchange at the Interface Between Westminster and Raqqa

Liminalities: A Journal of Performance Studies Vol. 16, No. 2 (2020) Monuments of Terrorism: (De)Selecting Memory and Symbolic Exchange at the Interface Between Westminster and Raqqa Theodore Price Contemporary conflict is conducted across multiple visual fronts, as the old visual symbols of conventional warfare and remembrance are increasingly replaced with digital images. Focusing on three events in the summer of 2015: the attack on tourists in Tunisia, the blowing up of the Temple of Bel in Palmyra, Syria, and the construction of a replica of the destroyed Arch of Triumph from Palmyra in Trafalgar Square, London, this paper details the symbolic exchange between the so-called Islamic State and western governments. Through an examination of the visual representation of violence enacted towards individual holidaymakers and ancient tourist sites, this paper details how the attack on a holiday resort in Tuni- sia was recast through a master narrative of war where the military repatriation of civilians represented the dead tourists as fallen soldiers. It will examine the visual record of the destruction of the Temple of Bel, by the Islamic State (ISIS), arguing that this action gained international legitimacy through the validation and complicity of the visual frame provided by satellite images from the United Na- tions. Finally, it will discuss the replication of the Arch of Triumph, from Palmyra, in Trafalgar Square as a further example of the instrumentalisation of counter- iconoclasm. In this paper I suggest that the new monuments to terrorism are images of the events themselves, rather than simply physical memorials built for remem- brance, and that these new monuments to terrorism circulating within the virtual landscapes of the internet, become the new sites of collective memorialisation Theodore Price is a London-based artist, curator and researcher whose practice is located at the intersection between art and politics. -

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

1. Introduction

This PDF is a simplified version of the original article published in Internet Archaeology. All links also go to the online version. Please cite this as: Nicholson, C., Fernandez, R. and Irwin, J. 2021 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States, Internet Archaeology 58. https://doi.org/10.11141/ia.58.22 Digital Archaeological Data in the Wild West: the challenge of practising responsible digital data archiving and access in the United States Christopher Nicholson, Rachel Fernandez and Jessica Irwin Summary Archaeology in the United States is conducted by a number of different sorts of entities under a variety of legal mandates that lack uniform standards for data archiving. The difficulty of accessing data from projects in which one was not directly involved indicates an apparent reluctance to archive raw data and supplemental information with digital repositories to be reused in the future. There is hope that additional legislation, guidelines from professional organisations, and educational efforts will change these practices. 1. Introduction Though we are well into the 21st century, responsible digital archiving of archaeological data in the United States is not common practice. Digital archiving of cultural resource management reports in State Historic Preservation Offices, where they are often available by request though perhaps at a cost, is common; however, digitally archiving the datasets and other supporting materials that went into the creation of those documents is not. Though a vocal minority advocates for responsible digital archiving practices (Kansa and Kansa 2013; 2018; Kansa et al. -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

On the Verge of Summer

#5 (99) May 2016 Chances of general elections Privatization of state-owned Romance novels and Ukrainian and vote in occupied Donbas companies: plans and obstacles society in the 1920s ON THE VERGE OF SUMMER WWW.UKRAINIANWEEK.COM Featuring selected content from The Economist FOR FREE DISTRIBUTION CONTENTS | 3 BRIEFING 26 Serhiy Hunko: “We cannot issue 5 The aggressive demon of victory: documents to unidentified persons“ The clash of memories on red-letter Press Officer for the State Migration days Service of Ukraine on IDPs and the role of Ukraine in international migration 7 Stanislav Kozliuk on public reaction to the scandal around the leak of 29 Geoff Wordley: “It looks like the journalists’ details by Myrotvorets main movements of IDPs have now stopped” FOCUS Head of UNHCR Sub-Office in 8 Bankova's sparring partners: Dnipropetrovsk about long-lasting Scenarios for cooperation between impact of forced migration on new Cabinet and President, and social and economic structure, and chances of early election assistance to IDPs in Ukraine 10 Division by zero: 32 An unwelcome host: What elections in the occupied Ukraine's place in modern migration Donbas would mean for all parties flows involved 34 Creativity and the town: 12 The harvest of hope: How locals encourage cultural Ukraine’s economy may be able to development at home through activism breathe more easily this coming 36 The battle for historical memory: summer How national memory shapes ECONOMICS the present and future in Ukraine 15 Ihor Bilous: "Foreign investors are CULTURE & ART -

Arsu and ‘Azizu a Study of the West Semitic "Dioscuri" and the Cods of Dawn and Dusk by Finn Ove Hvidberg-Hansen

’Arsu and ‘Azizu A Study of the West Semitic "Dioscuri" and the Cods of Dawn and Dusk By Finn Ove Hvidberg-Hansen Historiske-filosofiske Meddelelser 97 Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab The Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters DET KONGELIGE DANSKE VIDENSKABERNES SELSKAB udgiver følgende publikationsrækker: THE ROYAL DANISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES AND LETTERS issues the following series of publications: Authorized Abbreviations Historisk-filosofiske Meddelelser, 8° Hist.Fil.Medd.Dan.Vid.Selsk. (printed area 1 75 x 104 mm, 2700 units) Historisk-filosofiske Skrifter, 4° Hist.Filos.Skr.Dan.Vid.Selsk. (History, Philosophy, Philology, (printed area 2 columns, Archaeology, Art History) each 199 x 77 mm, 2100 units) Matematisk-fysiske Meddelelser, 8° Mat.Fys.Medd.Dan.Vid.Selsk. (Mathematics, Physics, (printed area 180 x 126 mm, 3360 units) Chemistry, Astronomy, Geology) Biologiske Skrifter, 4° Biol.Skr. Dan. Vid.Selsk. (Botany, Zoology, Palaeontology, (printed area 2 columns, General Biology) each 199 x 77 mm, 2100 units) Oversigt, Annual Report, 8° Overs. Dan.Vid.Selsk. General guidelines The Academy invites original papers that contribute significantly to research carried on in Denmark. Foreign contributions are accepted from temporary residents in Den mark, participants in a joint project involving Danish researchers, or those in discussion with Danish contributors. Instructions to authors Manuscripts from contributors who are not members of the Academy will be refereed by two members of the Academy. Authors of papers accepted for publication will re ceive galley proofs and page proofs; these should be returned promptly to the editor. Corrections other than of printer's errors will be charged to the author(s) insofar as the costs exceed 15% of the cost of typesetting. -

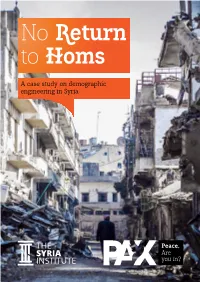

A Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria No Return to Homs a Case Study on Demographic Engineering in Syria

No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria No Return to Homs A case study on demographic engineering in Syria Colophon ISBN/EAN: 978-94-92487-09-4 NUR 689 PAX serial number: PAX/2017/01 Cover photo: Bab Hood, Homs, 21 December 2013 by Young Homsi Lens About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan research organization based in Washington, DC. TSI seeks to address the information and understanding gaps that to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the ongoing Syria crisis. We do this by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options that empower decision-makers and advance the public’s understanding. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Executive Summary 8 Table of Contents Introduction 12 Methodology 13 Challenges 14 Homs 16 Country Context 16 Pre-War Homs 17 Protest & Violence 20 Displacement 24 Population Transfers 27 The Aftermath 30 The UN, Rehabilitation, and the Rights of the Displaced 32 Discussion 34 Legal and Bureaucratic Justifications 38 On Returning 39 International Law 47 Conclusion 48 Recommendations 49 Index of Maps & Graphics Map 1: Syria 17 Map 2: Homs city at the start of 2012 22 Map 3: Homs city depopulation patterns in mid-2012 25 Map 4: Stages of the siege of Homs city, 2012-2014 27 Map 5: Damage assessment showing targeted destruction of Homs city, 2014 31 Graphic 1: Key Events from 2011-2012 21 Graphic 2: Key Events from 2012-2014 26 This report was prepared by The Syria Institute with support from the PAX team. -

Methods in Digital Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Katy Meyers Emery

Methods in Digital Archaeology and Cultural Heritage Katy Meyers Emery Increasingly over the last decade, anthropologists have looked to digital tools as a way to improve their interpretations, engage with the public and other professionals, collaborate with other disciplines, develop new technology to improve the discipline and more. Due to the increasing importance of digital, it is important that current students become equipped with the skills and confidence necessary to creatively and thoughtfully apply digital tools to cultural heritage questions. With that in mind, this course is not a lecture- it is an open discussion and development course where students will learn digital tools by using and making them. This course will provide students with an introduction to digital tools in archaeology, from using social media to engage with communities to developing their own online projects to preserve, protect, share and engage with cultural heritage and archaeology. Course Goals: 1. Understand and articulate the benefits and challenges of digital methods within archaeology and cultural heritage management 2. Critically use digital methods to engage with the public and archaeological community online to promote cultural and archaeological heritage and preservation (ex. Blogging, Twitter, Digital Mapping, etc) 3. Leverage digital tools to create a digital project focused on archaeology or cultural heritage Texts: All reading material for this course will be provided online, although students may need to request or find their own reading material related to a historic site for their final project. **This syllabus was designed based on a course that I helped develop and teach over summer 2014, a Mobile Cultural Heritage Informatics class I assisted in during summer 2011, and my years as a Cultural Heritage Informatics Initiative fellow. -

Between the Cults of Syria and Arabia: Traces of Pagan Religion at Umm Al-Jimål

!"#$%&"%'#(")*%+!"$,""-%$."%/01$)%23%45#(6%6-&%7#68(69%:#6;")%23%<6=6-%>"1(=(2-%6$% % ?@@%61AB(@61*C%!"#$%&'(%)("*&(+%'",-.(/)$(0-1*/&,2,3.(,4(5,-$/)(6D%7@@6-9% % E"F6#$@"-$%23%7-$(G0($(")%23%B2#&6-%HIJJKL9%MNNAMKMD% Bert de Vries Bert de Vries Department of History Calvin College Grand Rapids, MI 49546 U.S.A. Between the Cults of Syria and Arabia: Traces of Pagan Religion at Umm al-Jimål Introduction Such a human construction of religion as a so- Umm al-Jimål ’s location in the southern Hauran cial mechanism to achieve security does not pre- puts it at the intersection of the cultures of Arabia to clude the possibility that a religion may be based the south and Syria to the north. While its political on theological eternal verities (Berger 1969: 180- geography places it in the Nabataean and Roman 181). However, it does open up the possibility of an realms of Arabia, its cultural geography locates it archaeology of religion that transcends the custom- in the Hauran, linked to the northern Hauran. Seen ary descriptions of cult centers and cataloguing of on a more economic cultural axis, Umm al-Jimål altars, statues, implements and decorative elements. is between Syria as Bilåd ash-Shåm, the region of That is, it presupposes the possibility of a larger agricultural communities, and the Badiya, the re- interpretive context for these “traces” of religion gion of pastoral nomad encampments. Life of soci- using the methodology of cognitive archaeology. ety on these intersecting axes brought a rich variety The term “traces” is meant in the technical sense of economic, political and religious cross-currents of Assmann’s theory of memory (2002: 6-11). -

Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery

UCLA Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press Title Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/5xf6b5zd ISBN 978-1-938770-08-1 Author Scott, David A. Publication Date 2016-12-01 Data Availability The data associated with this publication are within the manuscript. Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Art: Authenticity, Restoration, ForgeryRestoration, Authenticity, Art: Forgery Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. Scott his book presents a detailed account of authenticity in the visual arts from the Palaeolithic to the postmodern. The restoration of works Tof art can alter the perception of authenticity, and may result in the creation of fakes and forgeries. These interactions set the stage for the subject of this book, which initially examines the conservation perspective, then continues with a detailed discussion of what “authenticity” means, and the philosophical background. Included are several case studies that discuss conceptual, aesthetic, and material authenticity of ancient and modern art in the context of restoration and forgery. • Scott Above: An artwork created by the author as a conceptual appropriation of the original Egyptian faience objects. Do these copies possess the same intangible authenticity as the originals? Photograph by David A. Scott On front cover: Cast of author’s hand with Roman mask. Photograph by David A. Scott MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 MLKRJBKQ> AO@E>BLILDF@> 35 CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CLQPBK IKPQFQRQB LC AO@E>BLILDV POBPP CIoA Press READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS READ ONLY/NO DOWNLOADS Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery David A. -

Monuments, Materiality, and Meaning in the Classical Archaeology of Anatolia

MONUMENTS, MATERIALITY, AND MEANING IN THE CLASSICAL ARCHAEOLOGY OF ANATOLIA by Daniel David Shoup A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Art and Archaeology) in The University of Michigan 2008 Doctoral Committee: Professor Elaine K. Gazda, Co-Chair Professor John F. Cherry, Co-Chair, Brown University Professor Fatma Müge Göçek Professor Christopher John Ratté Professor Norman Yoffee Acknowledgments Athena may have sprung from Zeus’ brow alone, but dissertations never have a solitary birth: especially this one, which is largely made up of the voices of others. I have been fortunate to have the support of many friends, colleagues, and mentors, whose ideas and suggestions have fundamentally shaped this work. I would also like to thank the dozens of people who agreed to be interviewed, whose ideas and voices animate this text and the sites where they work. I offer this dissertation in hope that it contributes, in some small way, to a bright future for archaeology in Turkey. My committee members have been unstinting in their support of what has proved to be an unconventional project. John Cherry’s able teaching and broad perspective on archaeology formed the matrix in which the ideas for this dissertation grew; Elaine Gazda’s support, guidance, and advocacy of the project was indispensible to its completion. Norman Yoffee provided ideas and support from the first draft of a very different prospectus – including very necessary encouragement to go out on a limb. Chris Ratté has been a generous host at the site of Aphrodisias and helpful commentator during the writing process. -

Musical (And Other) Gems from the State Library in Dresden

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 23, Number 20, May 10, 1996 Reviews Musical (and other) gems from the State Libraryin Dresden by Nora Hamennan One might easily ask how anything could be left of what was scribe, and illuminations by a Gentile artist painted in Chris once the glorious collection of books and manuscripts which tian Gothic style. An analogous "cross-cultural" blend is were the Saxon Royal Library, and then after 1918, Saxon shown in two French-language illuminated manuscripts of State Library in Dresden. After all, Dresden was razed to the works by Boccaccio and Petrarca, respectively, two of the ground by the infamous Allied firebombing in 1945, which "three crowns" of Italian 14th-century vernacular literature, demolished the Frauenkirche and the "Japanese Palace" that produced in the 15th-century French royal courts. Then had housed the library's most precious holdings, as well as comes a printed book, with hand-painted illuminations, of taking an unspeakable and unnecessary toll in innocent hu 1496, The Performanceo/Music in Latin by Francesco Gaffu man lives. Then, the Soviets, during their occupation of the rius, the music theorist whose career at the Milan ducal court eastern zone of Germany, carried off hundreds of thousands overlapped the sojourns there of Josquin des Prez, the most of volumes, most of which have not yet been repatriated. renowned Renaissance composer, and Leonardo da Vinci, The question is partially answered in the exhibit, "Dres regarded by contemporaries as the finestimprovisational mu den: Treasures from the Saxon State Library," on view at the sician.