Changes in Energy Content of Lunchtime Purchases from Fast Food Restaurants After Introduction of Calorie Labelling: Cross Sectional Customer Surveys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Panera Bread Co

Hospitality Review Volume 23 Article 4 Issue 1 Hospitality Review Volume 23/Issue 1 January 2005 Who Shook Big Mac?: Panera Bread Co. Kyuho Lee Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, [email protected] Melih Madanoglu Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/hospitalityreview Part of the Hospitality Administration and Management Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Kyuho and Madanoglu, Melih (2005) "Who Shook Big Mac?: Panera Bread Co.," Hospitality Review: Vol. 23 : Iss. 1 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/hospitalityreview/vol23/iss1/4 This work is brought to you for free and open access by FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hospitality Review by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Who Shook Big Mac?: Panera Bread Co. Abstract The uthora s identify the firm-specific orc e competencies that Panera Bread has relied on to achieve a competitive advantage in its business domain. The tudys illustrates how the company scans the dynamically changing environments and tailors their products and services in accordance with these changes. This article is available in Hospitality Review: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/hospitalityreview/vol23/iss1/4 Who shook Big Mac?: Panera Bread Co. by Kyuho Lee and Melih Madanoglil The authorr identi3 thefirm-per.~fir McDonald's Corporation, a company core competencier that Paizera Bread ha that has been in business since the relied on to achieve a comperitive 1950, reported irs historic firsr advantage in itr burinerr domain. -

Panera Bread and Au Bon Pain) and One on the West Cream Or Cheese

BY BONNIE LIEBMAN & JAYNE HURLEY cDonald’s is losing money. Last December, the fast- PANS Mfood giant posted its first quarterly loss since the com- ■ Turkey Artichoke Panini Sandwich. “Inspired by Italy, panini are sandwiches with fresh ingredients held between pany went public in 1965. Among the many explanations hearty bread and pressed on a hot grill,” says the menu. But both of Panera’s paninis have too much saturated fat (most- was one to make a nutritionist’s heart go all aflutter: “Time- ly from their cheese). The healthy-sounding Turkey pressed customers may increasingly be calorie- and fat-con- Artichoke Panini, for example, has as much saturated fat as a McDonald’s Big Mac (11 grams), but far more calories (850 scious and pickier about service and lifestyle issues…” ven- vs 590) and sodium (2,550 mg vs 1,090 mg). And that’s not tured The Washington Post. counting the potato chips that are served on the side. ■ Asiago Roast Beef Signature Sandwich. The Asiago As the fast-food chains stumble, what the industry calls “fast Roast Beef has 960 calories, 52 grams of fat (24 of them sat- casual” restaurants are gaining ground. No burger-and-fries urated), and 2,140 mg of sodium, not including the pickle spear and chips. That’s a Burger King Double Whopper, or buckets of chicken for these new upscale kids on the block. except the Roast Beef has twice as much sodium. Instead, you can order fast soups, salads, and sandwiches (or ■ Broccoli Cheddar Soup. The worst soup at Panera is one of a handful that are available every day. -

PHL Fullview

Stellar News Philly Pretzel Factory Hudson News Fire & IceSolstice XpresSpa Kiehl’s Stellar News Good 2 Go re:vive Soundbalance Local Tavern Red Mango Hudson News Smashburger Good 2 Go Far East Le Bus Cafe Sbarro Chipotle Tony Luke’s Au Bon Pain Hudson News TERMINAL F Coffee Good 2 Go Stellar News American Eagle Pennsylvania Market CNBC News 2016 Enplanements 2.6 million B-Iconic Life Is Good La Colombe Chickie’s & Pete’s Vera Bradley Hudson News/Dunkin’ Donuts Lick Chickie’s & Pete’s Tous Lids/Lids Kids Dunkin’ Donuts Travelex Sbarro XpresSpa Vino Volo StellarAu News Bon Pain Ruby Blue Subway McDonald’s Earl of Sandwich Timeless Travel Currito Burritos Tumi Au Bon Pain American Express Stellar News Tech Showcase Furla Travelex Gap JohnstonBody & Murphy ShopCoach HeritageSubway BooksChick-Fil-AGeno’s SmashburgerAsian ChaoPinkberryLegal SeaM.A.C FoodsFinish Line PhiladelphiaBrooks Marketplace Brothers Gachi Sushi & Noodle M.A.C. Good 2 Go Au Bon Pain Hudson News - Tech on the Go Travelex Worldwide Money Services UPS Store DFASS Minute Suites DN UP Stellar News Cantina Laredo Travelex XpresSpa CNBC News DFASS Explore Philadelphia BrightonInMotion L’Occitane Lids Victoria’s SunglassSecretTumi Hut Le Bus Cafe TERMINAL E Healthy Gourmet Pandora PGA TourSpanx Taxco Sterling Kiehl’s Vino Volo StarbucksPHL Sports La Colombe CNBC News Time to Fly Afaze Dunkin’ Donuts Famous Famiglia Jack Duggan’s Today Gachi Sushi & Noodle Sky Asian Bistro Frontier Airlines Currito Burritos Jack Duggan’s Cafe Auntie Anne’s Burrito Elito JetBlue Airways La Tapenade -

Dullesfoodandshops.Com

Main Terminal – Upper Level Concourse A Concourse C Ticketing (Pre-Security) SHOPS SHOPS DullesFoodandShops.com SHOPS Airport Wireless (Gate A31) AMERICA! (Gate C11) Forbes News (West) Burberry (Gate A32) Hudson Booksellers (Gate C18) Many new stores and restaurants will be opening iTravel 2 (West) InMotion Entertainment (Gate A24) Tax & Duty Free (Gate C4) in 2015. We apologize for any inaccuracies on this FOOD Montblanc (Gate A32) FOOD map as the airport continues to upgrade your retail Tax & Duty Free (Gate A32) Au Bon Pain (Gate C14) District ChopHouse (Center) and dining experience. SERVICES FOOD brb (be right burger) (Gate C14) Shoe Shine (East) Cosi (Gate A4) Auntie Anne’s (Gate C9) Currency Exchange (East & West) Dunkin’ Donuts (Gate A23) California Tortilla (Gate C19) The Firkin & Fox (Gate A3) The Firkin & Fox (Gate C19) C1 C2 Fuddruckers (Gate A22) Potbelly Sandwich Shop (Gate C2) Potbelly Main Terminal – Lower Level Great American Bagel Bakery (Gate A31) Starbucks (Gate C7) Sandwich Baggage Claim (Pre-Security) C3 Shop luv’n berry (Gate A22) Starbucks (Gate C24) Vino Volo C4 SHOPS Matsutake Sushi (Gate A23) Vino Volo Wine Room (Gate C3) A2 Wine Room Washington Informer (Baggage Claim #4) Old Dominion Bar (Gate A14) &pizza (Gate C28) Washingtonian News (Baggage Claim #13) Smashburger (Gate A5) SERVICES The Firkin Hudson News FOOD Starbucks (Gate A5) Shoe Shine (Gate C14) Cosi & Fox (Arriving Soon) Dulles Gourmet Market (Baggage Claim #14 – Villa Pizza (Gate A23) Smoking Lounge (Gate C4) Tax & open 24 hrs) SERVICES Currency -

On the Baylor Horizon...A Publication of the Division of Student Life

On the Baylor Horizon.....a publication of the Division of Student Life Special Edition: Fall Break 2016 Provided below is information on events, activities, and hours of operation of dining areas on campus. Friday, October 21 Moody/Jones Libraries, open 7 a.m.-11 p.m. o Moody Library Starbucks, open 7 a.m.-10:30 p.m. Bill Daniel Student Center (SUB), open 7 a.m.-5:30 p.m. Baylor Health Center and Pharmacy, open 8 a.m.-6 p.m. McLane Student Life Center (SLC), open 8 a.m.-8 p.m. Baylor Marina, closed Residential and Retail Dining Hours: o East Village, closed o Brooks, closed o Penland Crossroads . Breakfast, open 8-10 a.m. Lunch, open 10:45 a.m.-2 p.m. Dinner, open 4:30-7:30 p.m. Brunch, closed . Late Night, closed o 1845 at Memorial, closed o Baylor Sciences Building Starbucks, closed o Moe’s, closed o Which Wich, closed o Einstein’s, open 7 a.m.-12 noon o Panda Express, closed o Mooyah, open 10:30 a.m.-3 p.m. o Freshii, closed o SUB C-Store, closed o Chick-fil-A, open 7 a.m.-3 p.m. o Au bon pain, closed o Penland POD, closed o East Village Bakery, closed o Terrance/Law School Café, open 8 a.m.-2 p.m. Saturday, October 22 Baylor Health Center and Pharmacy, open 9 a.m.-1 p.m. Moody/Jones Libraries, open 9 a.m.-11 p.m. o Moody Library Starbucks, open 9 a.m.-10:30 p.m. -

This Brand Lives Its Mission of Bringing Hearty- Tasting Subs and a Heart for Community Service

This brand lives its mission of bringing hearty- tasting subs and a heart for community service. And we’re fully committed to helping campuses enhance their role within their local communities. - Greg Delks, VP Non-Traditional Development WHO IS FIREHOUSE SUBS? Rob Sorenson with his sons, Firehouse Chris and Robin Subs co-founders Sorenson remain Chris and Robin – active in Firehouse circa 1994 Subs operations. Founded in 1994 by brothers and former firefighters Chris and Robin Sorensen, Firehouse Subs is a brand built on decades of community service; steaming hot subs with the highest quality meats and cheeses; and a commitment to saving lives through the non-profit Firehouse Subs Public Safety Foundation. The founders are the real deal, the food is their creation and the franchise family shares their passion for food and community. THE MENU COLD SANDWICH OPTIONS FOR TURNKEY CATERING (SHOWN) AND GRAB-N-GO PROGRAMS 1,000 1,200 200 400 600 800 WHAT HAS FIREHOUSE SUBS DELIVERED? SUBS FIREHOUSE HAS WHAT 0 INDUSTRY LEADING FRANCHISEINDUSTRY RELATIONS 1994 48 STATES, CANADA, PUERTO RICO 1994 SYSTEM LOCATIONS 1995 1996 1997 CONSISTENT, MANAGED GROWTH MANAGED CONSISTENT, 1998 – 1999 2019 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 $ 728K 728K 2018 AUV 2019 ALMOST $50M IN LIFESAVING EQUIPMENT LIFESAVING IN $50M ALMOST TOTAL TOTAL U.S. COVERAGE Technomic Top-Box Ratings Technomic Top-Box Ratings Technomic Top-Box Ratings Sandwich + Bakery Segment, Q2 2019 - Q1 2020 Sandwich + Bakery Segment, Q2 2019 -

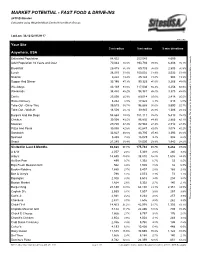

MARKET POTENTIAL - FAST FOOD & DRIVE-INS 2019 Estimates Calculated Using Weighted Block Centroid from Block Groups

MARKET POTENTIAL - FAST FOOD & DRIVE-INS 2019 Estimates Calculated using Weighted Block Centroid from Block Groups Lat/Lon: 36.1212/-95.9117 MRI_FAST Your Site 3 mi radius 5 mi radius 5 min drivetime Anywhere, USA Estimated Population 0 T 88,832 253,045 8,609 Adult Population 18 Years and Over 0 T - 70,063 78.9% 193,793 76.6% 6,806 79.1% Breakfast 0 T - 25,415 36.3% 69,733 36.0% 2,503 36.8% Lunch 0 T - 36,315 51.8% 100,032 51.6% 3,532 51.9% Snacks 0 T - 9,224 13.2% 25,184 13.0% 903 13.3% Supper And Dinner 0 T - 33,146 47.3% 90,325 46.6% 3,268 48.0% Weekdays 0 T - 43,169 61.6% 117,036 60.4% 4,258 62.6% Weekends 0 T - 34,488 49.2% 94,981 49.0% 3,373 49.6% Eat-In 0 T - 25,056 35.8% 69,014 35.6% 2,418 35.5% Home Delivery 0 T - 6,282 9.0% 17,622 9.1% 613 9.0% Take-Out - Drive-Thru 0 T - 35,519 50.7% 96,888 50.0% 3,590 52.7% Take-Out - Walk-In 0 T - 14,508 20.7% 39,945 20.6% 1,386 20.4% Burgers And Hot Dogs 0 T - 54,669 78.0% 151,111 78.0% 5,410 79.5% Chicken 0 T - 30,508 43.5% 86,892 44.8% 2,866 42.1% Mexican 0 T - 29,720 42.4% 82,982 42.8% 2,912 42.8% Pizza And Pasta 0 T - 30,055 42.9% 82,647 42.6% 3,074 45.2% Sandwich 0 T - 33,627 48.0% 88,795 45.8% 3,393 49.9% Seafood 0 T - 5,485 7.8% 16,029 8.3% 584 8.6% Snack 0 T - 21,285 30.4% 58,000 29.9% 1,942 28.5% Visited In Last 6 Months 0 T - 63,823 91.1% 175,744 90.7% 6,232 91.6% A & W 0 T - 2,057 2.9% 5,369 2.8% 240 3.5% Arby's 0 T - 14,440 20.6% 36,810 19.0% 1,655 24.3% Au Bon Pain 0 T - 499 0.7% 1,352 0.7% 33 0.5% Baja Fresh Mexican Grill 0 T - 562 0.8% 1,926 1.0% 32 0.5% Baskin-Robbins 0 T - 1,880 2.7% 5,407 2.8% 165 2.4% Ben & Jerry's 0 T - 798 1.1% 2,073 1.1% 72 1.1% Bojangles' 0 T - 2,308 3.3% 6,613 3.4% 204 3.0% Boston Market 0 T - 1,824 2.6% 5,302 2.7% 140 2.1% Burger King 0 T - 23,140 33.0% 64,130 33.1% 2,351 34.5% Captain D's 0 T - 2,533 3.6% 7,507 3.9% 257 3.8% Carl's Jr. -

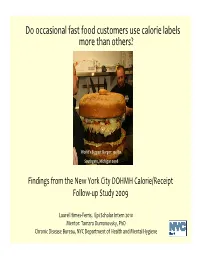

Do Occasional Fast Food Customers Use Calorie Labels More Than Others?

Do occasional fast food customers use calorie labels more than others? World’s Biggest Burger: 134 lbs. Southgate, Michigan 2008 Findings from the New York City DOHMH Calorie/Receipt Follow‐up Study 2009 Laurel Himes‐Ferris, Epi Scholar Intern 2010 Mentor: Tamara Dumanovsky, PhD Chronic Disease Bureau, NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene Obesity and Increased Calories: Parallel Epidemics • Obesity prevalence in the United States has more than doubled in the last 30 years • Increased calorie intake thought to play prominent role in obesity epidemic Men: +179 cal Women: +355 cal Figures from Jeffery and Harnack, 2008 Fast Food Intervention in NYC Rationale: • Consumption of fast food is steadily increasing (12% of all calories) •Population calorie increase may be associated with increased consumption of fast food over last 30 years •Fast food serves large portion sizes •People aren’t able to accurately estimate calorie content of food, especially as portion sizes increase Fast Food Intervention in NYC Implemented Summer, 2008: Calorie labels must be posted on menu boards of chain fast food stores Fast food store: place where one pays for food immediately after ordering Chain fast food store: fast food franchise with 15 or more stores Results from the Calorie/Receipt Study ‘09* 16% Used labels 84% Didn’t see or use labels Average calories purchased Average calories purchased 781 cal. 781 + 77 = 858 cal. *Adjusted for demographics and type of purchase Fast Food Intervention Nationwide: Calorie labels coming to Michigan: The 2009 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act mandates that chain fast food stores (20 or more stores) post calorie labels beginning in 2014. -

SECOND 100 Chain Index

SECOND 100 Chain Index LATEST YEAR RANKINGS SYSTEM- % GROWTH, % GROWTH, % GROWTH, SALES WIDE SYSTEM NO. OF NO. OF NO. OF PER COMPANY HEADQUARTERS PARENT COMPANY SEGMENT SALES SALES UNITS UNITS FRAN. UNITS UNIT A&W All American Food Lexington, Ky. A Great American Brand LLC (A&W Restaurants Inc.) LSR/Burger 167 23 7 87 49 99 Au Bon Pain Boston LNK Partners LLC Bakery-Cafe 108 62 33 67 29 55 Bahama Breeze Orlando, Fla. Darden Restaurants Inc. Casual Dining 169 50 93 36 — 11 Baja Fresh Mexican Grill Irvine, Calif. BF Acquisition Holdings LLC LSR/Mexican 183 91 44 89 50 72 Bar Louie Addison, Texas Sun Capital Partners Inc. Casual Dining 157 19 57 7 5 36 Barnes & Noble Café New York Barnes & Noble Inc. In-Store 130 81 6 64 — 95 Beef 'O' Brady's Family Tampa, Fla. Levine Leichtman Capital Partners (FSC Franchise Co. LLC) Casual Dining 172 78 36 73 44 74 Sports Pub Benihana of Tokyo Miami Angelo, Gordon & Co. Casual Dining 125 74 75 66 56 19 Bertucci's Italian Restaurant Northborough, Mass. Jacobson Partners Casual Dining 180 76 67 63 — 41 Big Boy/Frisch's Big Boy Warren, Mich./Cin- Big Boy Restaurants International LLC/ Family Dining 110 63 29 77 54 59 cinnati NRD Capital Management LLC Black Bear Diner Redding, Calif. Black Bear Diners Inc. Family Dining 187 14 72 19 15 31 Braum's Ice Cream and Oklahoma City W.H. Braum Inc. LSR/Burger 145 54 24 48 — 81 Dairy Stores Brio Tuscan Grille Columbus, Ohio Bravo Brio Restaurant Group Inc. -

Au Bon Pain Legal Sea Foods Off the Common at the Park Plaza Maggiano's Little Italy W

BLC15 – WHERE TO EAT SHOW YOUR CONFERENCE BADGE FOR A DISCOUNT Restaurants located on Park Plaza property or a short walk away Au Bon Pain www.aubonpain.com Off the Common at the Park Plaza 26 Park Plaza (617) 338-8948 50 Park Plaza (Our hotel lobby) (617) 457-1850 Serves upscale sandwiches, soups, and salads to go. M-F 6:30 am to midnight; Breakfast (Weekends) 7 am to 11 am Hours: M-F 6 am to 10 pm. Sat 6:30 am to 9 pm. Sun 7 am to 8 pm. Bar - 11 am to 1 am $1 off each ORDER ($5.00 minimum) with conference badge 15% off food only with conference badge Legal Sea Foods www.legalseafoods.com Maggiano’s Little Italy www.maggianos.com 26 Park Square (617) 426-4444 4 Columbus Ave. (Just across the street from the hotel!) (617) 542-3456 M-F 6:30 am to 12 pm; Breakfast Wkends 6:30 am to 12m; Sun 12n to 11 pm M-F 11:30 am to 10 pm; Sun 11:30 am to 11 pm Complimentary cup of award-winning clam chowder with Reservations recommended. conference badge and purchase of entrée 15% off food only with conference badge M. J. O’Connor’s Irish Pub www.mjoconnors.com 27 Columbus Ave (617) 482-2255 Irish pub/restaurant with a seating capacity of 250. Hours of operation: Sun-Sat 11:30 am to 2 am. 15% off food only with conference badge OTHER RESTAURANTS VERY NEAR THE HOTEL Stuart Street Food Court at 8-10 Park Plaza Clarendon Street California Pizza Kitchen 137 Stuart St. -

(DRAFT) Market Analysis & Strategic Development Recommendations

METHODOLOGICAL OVERVIEW & SUPPORTING EXHIBITS SPORTS & ENTERTAINMENT ZONES WASHINGTON, D.C. Prepared for the Capitol Riverfront, Southwest, and DowntownDC BIDs July 9, 2020 ABOUT RCLCO Since 1967, RCLCO has been the “first call” for real estate developers, investors, the public sector, and non-real estate companies and organizations seeking strategic and tactical advice regarding property investment, planning, and development. RCLCO leverages quantitative analytics and a strategic planning framework to provide end-to-end business planning and implementation solutions at an entity, portfolio, or project level. With the insights and experience gained over 50 years and thousands of projects–touching over $5B of real estate activity each year–RCLCO brings success to all product types across the United States and around the world. Learn more about RCLCO at www.RCLCO.com. REPORT AUTHORS Project Director: Erin Talkington, Managing Director ► P: (240) 396-2353 | E: [email protected] Project Manager: Jacob Ross, Vice President ► P: (240) 404-6811 | E: [email protected] Capitol Riverfront, Southwest, and DowntownDC BIDs | Methodological Overview & Supporting Exhibits | Sports & Entertainment Zones E4-11989.05 | July 9, 2020 | 2 OBJECTIVES & CONTENTS OBJECTIVES METHODOLOGICAL OVERVIEW 4 The Capitol Riverfront, DowntownDC, and Southwest Business Improvement Districts ► Sources of Revenue 5 (“BIDs”) engaged RCLCO to evaluate the fiscal and economic impact of the COVID- ► Potential Recovery Scenarios 6 19 pandemic and resulting social distancing regulations on sports and entertainment zones across the District. Specifically, RCLCO is focused on ascertaining the amount ► Capitol Riverfront Entertainment 7 of “missing” sales, meals, income, and real property taxes that the entertainment ► Downtown Entertainment 8 venues and surrounding retailers and restaurants would have otherwise generated to the District, but will be unable to produce due to the pandemic and resulting closures. -

Restaurant Guide

12th Community Involvement Training Conference Restaurants Guide Restaurants within Walking Distance of the Renaissance Arlington Capital View Hotel Cinnabar ($$) El Pollito ($) Hyatt Regency Crystal City – 0.0 miles 513 23rd Street – 0.37 miles Chesapeake Grill ($$$) Café Pizzaiolo ($) Hyatt Regency Crystal City – 0.0 miles 507 23rd Street – 0.37 miles Plaza Deli ($) Subway ($) 2711 Jefferson Davis Highway – 0.1 miles 525 23rd Street – 0.38 miles Khoinoor Dhaba ($) Chipotle Mexican Grill ($) 2800 South Eads Street – 0.13 miles 2231 Crystal Drive – 0.40 miles O’Malley’s Sports Pub ($$) Quiznos ($) 2650 Jefferson Davis Highway – 0.15 miles 2231 Crystal Drive – 0.40 miles McDonald’s ($) Corner Bakery Café ($) 2620 Jefferson Davis Highway – 0.16 miles 2200 Crystal Drive – 0.42 miles New Yorker Deli ($) Neramitra Thai Restaurant ($) 2461 South Clark Street – 0.21 miles 2200 Crystal Drive – 0.42 miles Century Café ($) Noodles and Company ($) 2450 Crystal Drive – 0.27 miles 2011 Crystal Drive – 0.52 miles Perfect Pita ($) Cosi ($) 2345 Crystal Drive – 0.32 miles 2011 Crystal Drive – 0.52 miles Mackey’s Public House ($$) Wall Street Deli ($) 320 23rd Street – 0.34 miles 2011 Crystal Drive – 0.52 miles Kabob Palace ($) Au Bon Pain ($) 2315 South Eads Street – 0.35 miles 2021 Jefferson Davis Highway – 0.52 miles 5 1 4 3 8 7 2 6 i R LEGEND Renaissance Hotel ■ A Shops at Crystal Park ■ Hotel Accommodations ■ B Shops at 2100 Crystal Drive ■ Interior Pedestrian Concourse ■ C Shops at the Mall Entrance/Exit ■ D Shops at 1750 Crystal Drive Restroom