UNIT 9 KINSHIP-II Kinship-II

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Série Antropologia 103 Three Essays on Anthropology in India

Universidade de Brasília Instituto de Ciências Humanas Departamento de Antropologia 70910.900 – Brasília, DF Fone: +55 61 3307 3006 Série Antropologia 103 Three essays on anthropology in India Mariza Peirano This issue brings together the translation into English of numbers 57, 65 and 83 of Série Antropologia. The present title replaces the former “Towards Anthropo- logical Reciprocity”, its designation from 1990 to 2010. 1990 Table of contents Introduction .............................................................................. 2 Acknowledgements .................................................................. 7 Paper 1: On castes and villages: reflections on a debate.............. 8 Paper 2: “Are you catholic?” Travel report, theoretical reflections and ethical perplexities ………………….. 26 Paper 3: Anthropological debates: the India – Europe dialogue ...................................................... 54 1 Introduction The three papers brought together in this volume of Série Antropologia were translated from Portuguese into English especially to make them available for an audience of non- Brazilian anthropologists and sociologists. The papers were written with the hope that a comparison of the Brazilian with the Indian academic experience could enlarge our understanding of the social, historical and cultural implications of the development of anthropology in different contexts. This project started in the late 1970’s when, as a graduate student at Harvard University, I decided to take a critical look at the dilemmas that face -

Placement of Children with Relatives

STATE STATUTES Current Through January 2018 WHAT’S INSIDE Placement of Children With Giving preference to relatives for out-of-home Relatives placements When a child is removed from the home and placed Approving relative in out-of-home care, relatives are the preferred placements resource because this placement type maintains the child’s connections with his or her family. In fact, in Placement of siblings order for states to receive federal payments for foster care and adoption assistance, federal law under title Adoption by relatives IV-E of the Social Security Act requires that they Summaries of state laws “consider giving preference to an adult relative over a nonrelated caregiver when determining a placement for a child, provided that the relative caregiver meets all relevant state child protection standards.”1 Title To find statute information for a IV-E further requires all states2 operating a title particular state, IV-E program to exercise due diligence to identify go to and provide notice to all grandparents, all parents of a sibling of the child, where such parent has legal https://www.childwelfare. gov/topics/systemwide/ custody of the sibling, and other adult relatives of the laws-policies/state/. child (including any other adult relatives suggested by the parents) that (1) the child has been or is being removed from the custody of his or her parents, (2) the options the relative has to participate in the care and placement of the child, and (3) the requirements to become a foster parent to the child.3 1 42 U.S.C. -

Socio-Economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu

Socio-economic Characteristics of Tribal Communities That Call Themselves Hindu Vinay Kumar Srivastava Religious and Development Research Programme Working Paper Series Indian Institute of Dalit Studies New Delhi 2010 Foreword Development has for long been viewed as an attractive and inevitable way forward by most countries of the Third World. As it was initially theorised, development and modernisation were multifaceted processes that were to help the “underdeveloped” economies to take-off and eventually become like “developed” nations of the West. Processes like industrialisation, urbanisation and secularisation were to inevitably go together if economic growth had to happen and the “traditional” societies to get out of their communitarian consciousness, which presumably helped in sustaining the vicious circles of poverty and deprivation. Tradition and traditional belief systems, emanating from past history or religious ideologies, were invariably “irrational” and thus needed to be changed or privatised. Developed democratic regimes were founded on the idea of a rational individual citizen and a secular public sphere. Such evolutionist theories of social change have slowly lost their appeal. It is now widely recognised that religion and cultural traditions do not simply disappear from public life. They are also not merely sources of conservation and stability. At times they could also become forces of disruption and change. The symbolic resources of religion, for example, are available not only to those in power, but also to the weak, who sometimes deploy them in their struggles for a secure and dignified life, which in turn could subvert the traditional or establish structures of authority. Communitarian identities could be a source of security and sustenance for individuals. -

Kin Relationships

In H. T. Reis & S. Sprecher (Eds.), Encyclopedia of human relationships (pp. 951-954). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Kin Relationships Kin relationships are traditionally defined as ties based on blood and marriage. They include lineal generational bonds (children, parents, grandparents, and great- grandparents), collateral bonds (siblings, cousins, nieces and nephews, and aunts and uncles), and ties with in-laws. An often-made distinction is that between primary kin (members of the families of origin and procreation) and secondary kin (other family members). The former are what people generally refer to as “immediate family,” and the latter are generally labeled “extended family.” Marriage, as a principle of kinship, differs from blood in that it can be terminated. Given the potential for marital break-up, blood is recognized as the more important principle of kinship. This entry questions the appropriateness of traditional definitions of kinship for “new” family forms, describes distinctive features of kin relationships, and explores varying perspectives on the functions of kin relationships. Questions About Definition Changes over the last thirty years in patterns of family formation and dissolution have given rise to questions about the definition of kin relationships. Guises of kinship have emerged to which the criteria of blood and marriage do not apply. Assisted reproduction is a first example. Births resulting from infertility treatments such as gestational surrogacy and in vitro fertilization with ovum donation challenge the biogenetic basis for kinship. A similar question arises for adoption, which has a history 2 going back to antiquity. Partnerships formed outside of marriage are a second example. Strictly speaking, the family ties of nonmarried cohabitees do not fall into the category of kin, notwithstanding the greater acceptance over time of consensual unions both formally and informally. -

On the Non-Existence of "Dravidian Kinship"

Edinburgh Papers In South Asian Studies Number 6, (1996) _____________________________________________________________________________ On the Non-Existence of "Dravidian Kinship" Anthony Good Social Anthropology School of Social & Political Studies University of Edinburgh For further information about the Centre and its activities, please contact the Convenor Centre for South Asian Studies, School of Social & Political Studies, University of Edinburgh, 55 George Square, Edinburgh EH8 9LL. e-mail: [email protected] web page: www.ed.ac.uk/sas/ ISBN: 1 900 795 05 1 Paper Price: £2 inc. postage and packing On the Non–Existence of “Dravidian Kinship”* Anthony Good The proposition underlying this paper is a simple one, namely, that there is no such thing as the Dravidian kinship system. Naturally, such a stark statement requires a great deal of qualification and explanation if it is to represent anything more than gratuitous iconoclasm. I shall try to satisfy that requirement in three ways, as follows. Empirically, I shall show using published ethnographic evidence that the great majority of Dravidian speakers in South Asia do not have a Dravidian kinship system as conventionally defined. Neither the relationship terminology nor the preferential marriage rules are in fact as they have been conventionally represented. Rather more briefly, I shall also claim that, taxonomically, “the Dravidian kinship system” forms one element in an inadequately constructed typology of kinship systems; while, theoretically, the notion of a “kinship system” leads to an overly static analysis, and involves an unacceptable degree of reification. First, however, it is necessary to say something about the nature of kinship, and explain why there is nonetheless an over–riding need to grasp it as a whole – though as a totality rather than as a system. -

Flexibility in Hare Social Organization

FLEXlBILITY IN HARE SOCIAL ORGANIZATION ¹ GUY LANOUE Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto, 100 St. George St., Toronto, Ontario, Canada, M5S 1A1 ABSTRACT/RESUME The Hare Indians of the NWT are characterized in terres of domestic groupe by two conflicting bases: those of the sibling groups which must co-operate, and those of conjugal units. The importance of both types of allegiances naturally creates a degree of tension and imposes care upon the negotiation of allegiances. La société des Indiens Hare des Territoires du Nord-Ouest est caractérisée par la présence de deux structures familiales en conflit: celle des enfants d'une morne famille, obligées à coopérer entre eux, et celle imposée par les liens conjugaux. La présence de ces deux orientations de ridE.litS crée naturel.lement chez les membres de cette société une certaine tendon et exige qu'ils portent à cet aspect de leurs relations une attention constante. 260 GUY LANOUE INTRODUCTION One striking feature of the anthropological descriptions of Athabascan Indian bands with bilateral, bifurcate-merging kinship terminology is the apparent lack of definite structurally-produced ru.les which might serve to provide an orientation for an individual's social action (cf. Helm 1956:131; Savashinsky 1974:xv, 194). The flexibility and negotiability of social relationships that usually appear to be associated with such systems are hot seen as positive features resulting from tendencies produced by structural regularities but rather are characterized as being the product of an absence of well defined sociologial reference points for the individual actor. This "definition by absence" does not appear to provide any useful insights into Athabascan social structure, as anthropological observers readily adroit that this negotiable feature of social relation- ships varies with the type of kin involved in the bilaterally-defined universe (cf. -

MAN-001 Social Anthropology Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences

MAN-001 Social Anthropology Indira Gandhi National Open University School of Social Sciences Block 1 INTRODUCTION TO SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY UNIT 1 Social Anthropology: Nature and Scope 5 UNIT 2 Philosophical and Historical Foundations of Social Anthropology 20 UNIT 3 Relationship of Social Anthropology with Allied Disciplines 30 Expert Committee Professor I J S Bansal Professor V.K.Srivastava Dr. S.M. Patnaik Retired, Department of Principal, Hindu College Associate Professor Human Biology University of Delhi Department of Anthropology Punjabi University, Patiala Delhi University of Delhi Delhi Professor K K Misra Professor Sudhakar Rao Director Department of Anthropology Dr. Manoj Kumar Singh Indira Gandhi Rashtriya University of Hyderabad Assistant Professor Manav Sangrahalaya Hyderabad Department of Anthropology Bhopal University of Delhi Professor. Subhadra M. Delhi Professor Ranjana Ray Channa Retired, Department of Department of Anthropology Faculty of Anthropology Anthropology University of Delhi SOSS, IGNOU Calcutta University, Kolkata Delhi Dr. Rashmi Sinha Professor P. Chengal Reddy Professor P Vijay Prakash Reader Retired, Department of Department of Anthropology Anthropology Andhra University Dr. Mitoo Das S V University, Tirupati Visakhapatnam Assistant Professor Professor R. K. Pathak Dr. Nita Mathur Dr. Rukshana Zaman Department of Anthropology Associate Professor Assistant Professor Panjab University Faculty of Sociology Dr. P. Venkatrama Chandigarh School of Social Sciences Assistant Professor Indira Gandhi National Open Professor A K Kapoor University, New Delhi Dr. K. Anil Kumar Department of Anthropology Assistant Professor University of Delhi, Delhi Programme Coordinator: Dr. Rashmi Sinha, IGNOU, New Delhi Course Coordinator : Dr. Rukshana Zaman, IGNOU, New Delhi Block Preparation Team Unit Writers Unit 3 Content Editor Unit 1 Dr. -

The Extent to Which the Classificatory Kinship System Cor- Responds To

T H R E E NO R M S O F SE X A N D MA R R I A G E I N LI G H T O F CL A S S I F I C AT O RY KI N S H I P 1 [26–35; 45–61; 149–161; 75–82] L E T U S N O W E X A M I N E the extent to which the classificatory kinship system cor- responds to modern norms of sexual intercourse and marriage. Among the Gilyak, at the present time at least, there is no question of any general prohibition of extra- marital sexual intercourse. Sexual intercourse with a woman is to the Gilyak a nat- ural act, as insignificant morally as any other natural act answering the well-known needs of man. Prohibitions and limitations extend only to definite groups of persons bound by agnatic or cognatic relationship. Outside of these groups, sexual interco u r s e is not subject to any regulation, nor to religious or public condemnation [75]. Besides the prohibitions determined by relationship, extramarital intercourse knows only one restriction, the reactions of the concerned persons. The young men of a clan who have access to the women of a certain locality, when displeased with a usurper, may give full vent to their resentment for his trespassing. Such cases are, ho w e v e r , very rare. The consequences are much more serious when a married woman is the source of trouble. A stranger caught in flagrante delicto with a married woman is killed by the husband on the spot. -

Indian Anthropology

INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY HISTORY OF ANTHROPOLOGY IN INDIA Dr. Abhik Ghosh Senior Lecturer, Department of Anthropology Panjab University, Chandigarh CONTENTS Introduction: The Growth of Indian Anthropology Arthur Llewellyn Basham Christoph Von-Fuhrer Haimendorf Verrier Elwin Rai Bahadur Sarat Chandra Roy Biraja Shankar Guha Dewan Bahadur L. K. Ananthakrishna Iyer Govind Sadashiv Ghurye Nirmal Kumar Bose Dhirendra Nath Majumdar Iravati Karve Hasmukh Dhirajlal Sankalia Dharani P. Sen Mysore Narasimhachar Srinivas Shyama Charan Dube Surajit Chandra Sinha Prabodh Kumar Bhowmick K. S. Mathur Lalita Prasad Vidyarthi Triloki Nath Madan Shiv Raj Kumar Chopra Andre Beteille Gopala Sarana Conclusions Suggested Readings SIGNIFICANT KEYWORDS: Ethnology, History of Indian Anthropology, Anthropological History, Colonial Beginnings INTRODUCTION: THE GROWTH OF INDIAN ANTHROPOLOGY Manu’s Dharmashastra (2nd-3rd century BC) comprehensively studied Indian society of that period, based more on the morals and norms of social and economic life. Kautilya’s Arthashastra (324-296 BC) was a treatise on politics, statecraft and economics but also described the functioning of Indian society in detail. Megasthenes was the Greek ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya from 324 BC to 300 BC. He also wrote a book on the structure and customs of Indian society. Al Biruni’s accounts of India are famous. He was a 1 Persian scholar who visited India and wrote a book about it in 1030 AD. Al Biruni wrote of Indian social and cultural life, with sections on religion, sciences, customs and manners of the Hindus. In the 17th century Bernier came from France to India and wrote a book on the life and times of the Mughal emperors Shah Jahan and Aurangzeb, their life and times. -

Dna by the Entirety

DNA BY THE ENTIRETY Natalie Ram The law fails to accommodate the inconvenient fact that an individual’s identifiable genetic information is involuntarily and immutably shared with her close genetic relatives. Legal institutions have established that individuals have a cognizable interest in control- ling genetic information that is identifying to them. The Supreme Court recognized in Maryland v. King that the Fourth Amendment is impli- cated when arrestees’ DNA is analyzed, and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act protects individuals from genetic discrimination in the employment and health-insurance markets. But genetic infor- mation is not like other forms of private or personal information because it is shared—immutably and involuntarily—in ways that are identifying of both the source and that person’s close genetic relatives. Standard approaches to addressing interests in genetic information have largely failed to recognize this characteristic, treating such infor- mation as individualistic. While many legal frames may be brought to bear on this problem, this Article focuses on the law of property. Specifically, looking to the law of tenancy by the entirety, this Article proposes one possible frame- work for grappling with the overlapping interests implicated in genetic identification and analysis. Tenancy by the entirety, like interests in shared identifiable genetic information, calls for the difficult task of conceptualizing two persons as one. The law of tenancy by the entirety thus provides a useful analytical framework for considering how legal institutions might take interests in shared identifiable genetic infor- mation into account. This Article examines how this framework may shape policy approaches in three domains: forensic identification, genetic research, and personal genetic testing. -

Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 104 | Issue 3 Article 4 2016 Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles University of Dayton School of Law Shelly Kreiczer-Levy College of Law and Business in Ramat Gan Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the Family Law Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Laufer-Ukeles, Pamela and Kreiczer-Levy, Shelly (2016) "Family Formation and the Home," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 104 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol104/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Family Formation and the Home Pamela Laufer-Ukeles' & Shelly Kreiczer-Levj INTRODUCTION' In this article, we consider the relevance of home sharing in family formation. When couples or groups of persons are recognized as families, they are afforded significant benefits and given certain obligations by the law.4 Families have their own category of laws, rights, and obligations.' Currently, the law of family formation and recognition is in a state of flux. Although in some respects the defining legal lines of the family have been well settled for centuries around blood and the formal legal ties of marriage and parenthood, in significant ways, the family form has been fundamentally altered over the past few decades. -

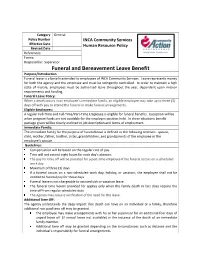

Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral Leave Is a Benefit Extended to Employees of INCA Community Services

Category General Policy Number INCA Community Services Effective Date Human Resource Policy Revised Date References: Forms: Responsible: Supervisor Funeral and Bereavement Leave Benefit Purpose/Introduction Funeral leave is a benefit extended to employees of INCA Community Services. Leave represents money for both the agency and the employee and must be stringently controlled. In order to maintain a high state of morale, employees must be authorized leave throughout the year, dependent upon mission requirements and funding. Funeral Leave Policy: When a death occurs in an employee’s immediate family, an eligible employee may take up to three (3) days off with pay to attend the funeral or make funeral arrangements. Eligible Employees: A regular Full-Time and Full-Time/Part-Time Employee is eligible for funeral benefits. Exception will be when program funds are not available for the employee position held. In these situations benefit package given will be clearly outlined in job description and terms of employment. Immediate Family: The immediate family for the purpose of funeral leave is defined as the following relatives: spouse, child, mother, father, brother, sister, grandchildren, and grandparents of the employee or the employee’s spouse. Guidelines: Compensation will be based on the regular rate of pay. Time will not exceed eight hours for each day’s absence. The pay for time off will be prorated for a part-time employee if the funeral occurs on a scheduled work day. Maximum of three (3) days. If a funeral occurs on a non-scheduled work day, holiday, or vacation, the employee shall not be entitled to funeral pay for those days.