Algae and Algae Pressing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

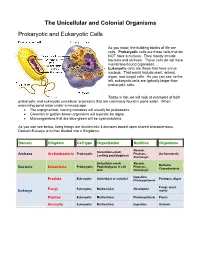

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Coral Reef Algae

Coral Reef Algae Peggy Fong and Valerie J. Paul Abstract Benthic macroalgae, or “seaweeds,” are key mem- 1 Importance of Coral Reef Algae bers of coral reef communities that provide vital ecological functions such as stabilization of reef structure, production Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive eco- of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary systems on the planet, forming heterogeneous habitats that production, and trophic support. Macroalgae of an astonish- serve as important sources of primary production within ing range of diversity, abundance, and morphological form provide these equally diverse ecological functions. Marine tropical marine environments (Odum and Odum 1955; macroalgae are a functional rather than phylogenetic group Connell 1978). Coral reefs are located along the coastlines of comprised of members from two Kingdoms and at least over 100 countries and provide a variety of ecosystem goods four major Phyla. Structurally, coral reef macroalgae range and services. Reefs serve as a major food source for many from simple chains of prokaryotic cells to upright vine-like developing nations, provide barriers to high wave action that rockweeds with complex internal structures analogous to buffer coastlines and beaches from erosion, and supply an vascular plants. There is abundant evidence that the his- important revenue base for local economies through fishing torical state of coral reef algal communities was dominance and recreational activities (Odgen 1997). by encrusting and turf-forming macroalgae, yet over the Benthic algae are key members of coral reef communities last few decades upright and more fleshy macroalgae have (Fig. 1) that provide vital ecological functions such as stabili- proliferated across all areas and zones of reefs with increas- zation of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient ing frequency and abundance. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Classification of Botany and Use of Plants

SECTION 1: CLASSIFICATION OF BOTANY AND USE OF PLANTS 1. Introduction Botany refers to the scientific study of the plant kingdom. As a branch of biology, it mainly accounts for the science of plants or ‘phytobiology’. The main objective of the this section is for participants, having completed their training, to be able to: 1. Identify and classify various types of herbs 2. Choose the appropriate categories and types of herbs for breeding and planting 1 2. Botany 2.1 Branches – Objectives – Usability Botany covers a wide range of scientific sub-disciplines that study the growth, reproduction, metabolism, morphogenesis, diseases, and evolution of plants. Subsequently, many subordinate fields are to appear, such as: Systematic Botany: its main purpose the classification of plants Plant morphology or phytomorphology, which can be further divided into the distinctive branches of Plant cytology, Plant histology, and Plant and Crop organography Botanical physiology, which examines the functions of the various organs of plants A more modern but equally significant field is Phytogeography, which associates with many complex objects of research and study. Similarly, other branches of applied botany have made their appearance, some of which are Phytopathology, Phytopharmacognosy, Forest Botany, and Agronomy Botany, among others. 2 Like all other life forms in biology, plant life can be studied at different levels, from the molecular, to the genetic and biochemical, through to the study of cellular organelles, cells, tissues, organs, individual plants, populations and communities of plants. At each of these levels a botanist can deal with the classification (taxonomy), structure (anatomy), or function (physiology) of plant life. -

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual - pages 95-115) Major Characteristics Algae 1. Cbaracteristics 2. Classification 3. Division Cblorophyta 4. Division Chrysophyta 5. Division Phaeopbyta 6. Division Rhodopbyta Protozoans 1. Characteristics 2. Classification 3. Class FlageUata 4. Class Sarcodina 5. Class Ciliata 6. Class Sporozoa I Biology I Lecture Notes 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual- pages 95-115) Major Characteristics I. Protists possess eukaryotic cells with well defined nuclei and organelles 2. Most are unicellular, however there are multi-cellularforms 3. They are diverse in their structure 4. They vary in size from microscope algae to kelp that can be over 100feet in length 5. They are diverse (like bacteria) in the way they meet their nutritional needs A . Some are photosynthetic like land plants - are autotrophic B. Some ingest theirfood like animals - heterotrophic by ingestion C. Some absorb theirfood like bacteria andfungi - heterotrophic by absorption D. One species - Euglena - is mixotrophic meaning that it is capable ofboth autotrophic and heterotrophic life styles. 6. Reproduction in Protists A. is usually asexual by mitosis B. sexual reproduction involves meiosis and spore formation and usualJy occurs only when environmental conditions are hostile C. spores are resistant and can withstand adverse conditions 7. Some protozoans form cysts - a type ofresting stage 8. Photosynthetic protists (mostly algae) are part ofplankton. Plankton are those organisms suspended infresh and marine waters that serve asfood for -- heterotrophic animals and other protists 9. There are diverse opinions on how to classify members ofthe Kingdom Protista. -

Brown Algae and 4) the Oomycetes (Water Molds)

Protista Classification Excavata The kingdom Protista (in the five kingdom system) contains mostly unicellular eukaryotes. This taxonomic grouping is polyphyletic and based only Alveolates on cellular structure and life styles not on any molecular evidence. Using molecular biology and detailed comparison of cell structure, scientists are now beginning to see evolutionary SAR Stramenopila history in the protists. The ongoing changes in the protest phylogeny are rapidly changing with each new piece of evidence. The following classification suggests 4 “supergroups” within the Rhizaria original Protista kingdom and the taxonomy is still being worked out. This lab is looking at one current hypothesis shown on the right. Some of the organisms are grouped together because Archaeplastida of very strong support and others are controversial. It is important to focus on the characteristics of each clade which explains why they are grouped together. This lab will only look at the groups that Amoebozoans were once included in the Protista kingdom and the other groups (higher plants, fungi, and animals) will be Unikonta examined in future labs. Opisthokonts Protista Classification Excavata Starting with the four “Supergroups”, we will divide the rest into different levels called clades. A Clade is defined as a group of Alveolates biological taxa (as species) that includes all descendants of one common ancestor. Too simplify this process, we have included a cladogram we will be using throughout the SAR Stramenopila course. We will divide or expand parts of the cladogram to emphasize evolutionary relationships. For the protists, we will divide Rhizaria the supergroups into smaller clades assigning them artificial numbers (clade1, clade2, clade3) to establish a grouping at a specific level. -

Evolution of Land Plants P

Chapter 4. The evolutionary classification of land plants The evolutionary classification of land plants Land plants evolved from a group of green algae, possibly as early as 500–600 million years ago. Their closest living relatives in the algal realm are a group of freshwater algae known as stoneworts or Charophyta. According to the fossil record, the charophytes' growth form has changed little since the divergence of lineages, so we know that early land plants evolved from a branched, filamentous alga dwelling in shallow fresh water, perhaps at the edge of seasonally-desiccating pools. The biggest challenge that early land plants had to face ca. 500 million years ago was surviving in dry, non-submerged environments. Algae extract nutrients and light from the water that surrounds them. Those few algae that anchor themselves to the bottom of the waterbody do so to prevent being carried away by currents, but do not extract resources from the underlying substrate. Nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, together with CO2 and sunlight, are all taken by the algae from the surrounding waters. Land plants, in contrast, must extract nutrients from the ground and capture CO2 and sunlight from the atmosphere. The first terrestrial plants were very similar to modern mosses and liverworts, in a group called Bryophytes (from Greek bryos=moss, and phyton=plants; hence “moss-like plants”). They possessed little root-like hairs called rhizoids, which collected nutrients from the ground. Like their algal ancestors, they could not withstand prolonged desiccation and restricted their life cycle to shaded, damp habitats, or, in some cases, evolved the ability to completely dry-out, putting their metabolism on hold and reviving when more water arrived, as in the modern “resurrection plants” (Selaginella). -

Plant:Animal Cell Comparison

Comparing Plant And Animal Cells http://khanacademy.org/video?v=Hmwvj9X4GNY Plant Cells shape - most plant cells are squarish or rectangular in shape. amyloplast (starch storage organelle)- an organelle in some plant cells that stores starch. Amyloplasts are found in starchy plants like tubers and fruits. cell membrane - the thin layer of protein and fat that surrounds the cell, but is inside the cell wall. The cell membrane is semipermeable, allowing some substances to pass into the cell and blocking others. cell wall - a thick, rigid membrane that surrounds a plant cell. This layer of cellulose fiber gives the cell most of its support and structure. The cell wall also bonds with other cell walls to form the structure of the plant. chloroplast - an elongated or disc-shaped organelle containing chlorophyll. Photosynthesis (in which energy from sunlight is converted into chemical energy - food) takes place in the chloroplasts. chlorophyll - chlorophyll is a molecule that can use light energy from sunlight to turn water and carbon dioxide gas into glucose and oxygen (i.e. photosynthesis). Chlorophyll is green. cytoplasm - the jellylike material outside the cell nucleus in which the organelles are located. Golgi body - (or the golgi apparatus or golgi complex) a flattened, layered, sac-like organelle that looks like a stack of pancakes and is located near the nucleus. The golgi body modifies, processes and packages proteins, lipids and carbohydrates into membrane-bound vesicles for "export" from the cell. lysosome - vesicles containing digestive enzymes. Where the digestion of cell nutrients takes place. mitochondrion - spherical to rod-shaped organelles with a double membrane. -

Plant Evolution and Diversity B. Importance of Plants C. Where Do Plants Fit, Evolutionarily? What Are the Defining Traits of Pl

Plant Evolution and Diversity Reading: Chap. 30 A. Plants: fundamentals I. What is a plant? What does it do? A. Basic structure and function B. Why are plants important? - Photosynthesize C. What are plants, evolutionarily? -CO2 uptake D. Problems of living on land -O2 release II. Overview of major plant taxa - Water loss A. Bryophytes (seedless, nonvascular) - Water and nutrient uptake B. Pterophytes (seedless, vascular) C. Gymnosperms (seeds, vascular) -Grow D. Angiosperms (seeds, vascular, and flowers+fruits) Where? Which directions? II. Major evolutionary trends - Reproduce A. Vascular tissue, leaves, & roots B. Fertilization without water: pollen C. Dispersal: from spores to bare seeds to seeds in fruits D. Life cycles Æ reduction of gametophyte, dominance of sporophyte Fig. 1.10, Raven et al. B. Importance of plants C. Where do plants fit, evolutionarily? 1. Food – agriculture, ecosystems 2. Habitat 3. Fuel and fiber 4. Medicines 5. Ecosystem services How are protists related to higher plants? Algae are eukaryotic photosynthetic organisms that are not plants. Relationship to the protists What are the defining traits of plants? - Multicellular, eukaryotic, photosynthetic autotrophs - Cell chemistry: - Chlorophyll a and b - Cell walls of cellulose (plus other polymers) - Starch as a storage polymer - Most similar to some Chlorophyta: Charophyceans Fig. 29.8 Points 1. Photosynthetic protists are spread throughout many groups. 2. Plants are most closely related to the green algae, in particular, to the Charophyceans. Coleochaete 3. -

Junior & Senior Horticulture Plant Parts Study Guide

JUNIOR & SENIOR HORTICULTURE PLANT PARTS STUDY GUIDE By Jerry Mills, Horticulture Educator Reviewed by Rhoda Burrows, SDSU Horticulture Specialist Spring 2007 The basic parts of most all plants are seeds, roots, stems, leaves, flowers and fruits. SEEDS: From the Beginner Horticulture Plant Parts Study Guide you learned: “The main purpose of seeds is to make new plants. Each seed contains a tiny plant called an embryo that can grow into an entirely new adult plant. When a seed sprouts, it will grow a tiny root and one or two tiny leaves. The leaves and root will get a little energy from the seed, and then will start working just like an adult plant to make its own food. Some of the seeds we eat are dried, such as beans, rice, and barley. Some are ground into flour (wheat), or meal (corn). Others are immature (green peas and sweet corn).” A typical seed has a seed coat, called a testa, an embryo and food for the embryo to feed on when the seed germinates. A cotyledon is the part of a seed that contains food for the baby plant until it can grow up to make food with its own leaves. Plants with one cotyledon (like corn) are called monocotyledon or monocot. The monocot embryo gets its first food from the endosperm. Plants with two cotyledons (like beans) are called dicotyledon or dicot and the embryo gets its first food from the two cotyledons. When the seed germinates, the plumule becomes the shoot that produces the first true leaves and the radicle becomes the first root. -

SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE

National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE National Plant Monitoring Scheme SPECIES IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Contents White / Cream ................................ 2 Grasses ...................................... 130 Yellow ..........................................33 Rushes ....................................... 138 Red .............................................63 Sedges ....................................... 140 Pink ............................................66 Shrubs / Trees .............................. 148 Blue / Purple .................................83 Wood-rushes ................................ 154 Green / Brown ............................. 106 Indexes Aquatics ..................................... 118 Common name ............................. 155 Clubmosses ................................. 124 Scientific name ............................. 160 Ferns / Horsetails .......................... 125 Appendix .................................... 165 Key Traffic light system WF symbol R A G Species with the symbol G are For those recording at the generally easier to identify; Wildflower Level only. species with the symbol A may be harder to identify and additional information is provided, particularly on illustrations, to support you. Those with the symbol R may be confused with other species. In this instance distinguishing features are provided. Introduction This guide has been produced to help you identify the plants we would like you to record for the National Plant Monitoring Scheme. There is an index at