Salinity Stress Responses and Adaptation Mechanisms in Eukaryotic Green Microalgae

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identification of Early Salinity Stress-Responsive Proteins In

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Identification of Early Salinity Stress-Responsive Proteins in Dunaliella salina by isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ)-Based Quantitative Proteomic Analysis Yuan Wang 1,2,†, Yuting Cong 2,†, Yonghua Wang 3, Zihu Guo 4, Jinrong Yue 2, Zhenyu Xing 2, Xiangnan Gao 2 and Xiaojie Chai 2,* 1 Key Laboratory of Hydrobiology in Liaoning Province’s Universities, Dalian Ocean University, Dalian 116021, China; [email protected] 2 College of fisheries and life science, Dalian Ocean University, Dalian 116021, China; [email protected] (Y.C.); [email protected] (J.Y.); [email protected] (Z.X.); [email protected] (X.G.) 3 Bioinformatics Center, College of Life Sciences, Northwest A&F University, Yangling 712100, China; [email protected] 4 College of Life Sciences, Northwest University, Xi’an, Shaanxi 710069, China; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] † These authors contribute equally to the work. Received: 22 November 2018; Accepted: 16 January 2019; Published: 30 January 2019 Abstract: Salt stress is one of the most serious abiotic factors that inhibit plant growth. Dunaliella salina has been recognized as a model organism for stress response research due to its high capacity to tolerate extreme salt stress. A proteomic approach based on isobaric tags for relative and absolute quantitation (iTRAQ) was used to analyze the proteome of D. salina during early response to salt stress and identify the differentially abundant proteins (DAPs). A total of 141 DAPs were identified in salt-treated samples, including 75 upregulated and 66 downregulated DAPs after 3 and 24 h of salt stress. -

A Mini Review-Effect of Dunaliella Salina on Growth and Health of Shrimps

International Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Studies 2020; 8(5): 317-319 E-ISSN: 2347-5129 P-ISSN: 2394-0506 (ICV-Poland) Impact Value: 5.62 A mini review-effect of Dunaliella salina on growth and (GIF) Impact Factor: 0.549 IJFAS 2020; 8(5): 317-319 health of shrimps © 2020 IJFAS www.fisheriesjournal.com Received: 08-07-2020 Dian Yuni Pratiwi Accepted: 14-08-2020 Dian Yuni Pratiwi Abstract Lecturer of Faculty, Department Dunaliella salina is a unicellular green algae that can be used as a natural food for shrimp. This of Fisheries and Marine Science, microalgae provides various nutrients such as protein, carbohydrates, lipids, pigments and others. Several Universitas Padjadjaran, studies have shown that Dunaliella salina can increase the growth performance of shrimps. Not only that, Indonesia Dunaliella salina also grant various health effects. High β-carotene and phenol in Dunaliella salina can increase immune system. This review was examined the optimum growth condition for Dunaliellla salina, nutrition contained in Dunaliella salina, and effect of Dunaliella salina for growth and health of shrimps such as Fenneropenaeus indicus, Penaeus monodon, and Litopenaeus vannamei. This review recommendation for Dunaliella salina as a potential feed for other. Keywords: Dunaliella salina, Fenneropenaeus indicus, Penaeus monodon, Litopenaeus vannamei, growth, health 1. Introduction Shrimp is one of popular seafood in the world community. The United States, China, Europe, and Japan are the major consuming regions, while Indonesia, China, India, Vietnam are major producing regions. In 2019, the global shrimp market size reached a volume of 5.10 Million [1] Tons . Popular types of shrimp for consumption are Litopenaeus vannamei, Penaeus monodon [1] and Fenneropenaeus indicus [2]. -

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes

Algae & Marine Plants of Point Reyes Green Algae or Chlorophyta Genus/Species Common Name Acrosiphonia coalita Green rope, Tangled weed Blidingia minima Blidingia minima var. vexata Dwarf sea hair Bryopsis corticulans Cladophora columbiana Green tuft alga Codium fragile subsp. californicum Sea staghorn Codium setchellii Smooth spongy cushion, Green spongy cushion Trentepohlia aurea Ulva californica Ulva fenestrata Sea lettuce Ulva intestinalis Sea hair, Sea lettuce, Gutweed, Grass kelp Ulva linza Ulva taeniata Urospora sp. Brown Algae or Ochrophyta Genus/Species Common Name Alaria marginata Ribbon kelp, Winged kelp Analipus japonicus Fir branch seaweed, Sea fir Coilodesme californica Dactylosiphon bullosus Desmarestia herbacea Desmarestia latifrons Egregia menziesii Feather boa Fucus distichus Bladderwrack, Rockweed Haplogloia andersonii Anderson's gooey brown Laminaria setchellii Southern stiff-stiped kelp Laminaria sinclairii Leathesia marina Sea cauliflower Melanosiphon intestinalis Twisted sea tubes Nereocystis luetkeana Bull kelp, Bullwhip kelp, Bladder wrack, Edible kelp, Ribbon kelp Pelvetiopsis limitata Petalonia fascia False kelp Petrospongium rugosum Phaeostrophion irregulare Sand-scoured false kelp Pterygophora californica Woody-stemmed kelp, Stalked kelp, Walking kelp Ralfsia sp. Silvetia compressa Rockweed Stephanocystis osmundacea Page 1 of 4 Red Algae or Rhodophyta Genus/Species Common Name Ahnfeltia fastigiata Bushy Ahnfelt's seaweed Ahnfeltiopsis linearis Anisocladella pacifica Bangia sp. Bossiella dichotoma Bossiella -

The Ppz Protein Phosphatases Are Key Regulators of K+ and Ph Homeostasis: Implications for Salt Tolerance, Cell Wall Integrity and Cell Cycle Progression

The EMBO Journal Vol. 21 No. 5 pp. 920±929, 2002 The Ppz protein phosphatases are key regulators of K+ and pH homeostasis: implications for salt tolerance, cell wall integrity and cell cycle progression Lynne Yenush, Jose M.Mulet, but the mechanisms that regulate their activity to achieve JoaquõÂn ArinÄ o1 and Ramo n Serrano2 cation homeostasis are only starting to be elucidated (Serrano and Rodriguez-Navarro, 2001). Instituto de BiologõÂa Molecular y Celular de Plantas, Universidad PoliteÂcnica de Valencia-CSIC, Camino de Vera s/n, Several lines of evidence have indicated the existence of E-46022 Valencia and 1Departament de BioquõÂmica i Biologia a link between cation homeostasis and the cell cycle. Molecular, Fac. VeterinaÁria, Universitat AutoÁnoma de Barcelona, Speci®cally, previous studies have established a correl- Bellaterra 08193, Barcelona, Spain ation between cytosolic alkalinization and G1 progression 2Corresponding author in yeast (Gillies et al., 1981) and animal cells (Nuccitelli e-mail: [email protected] and Heiple, 1982). This increased intracellular pH may be either a regulatory signal (Perona and Serrano, 1988) or The yeast Ppz protein phosphatases and the Hal3p merely permissive for cell proliferation (Grinstein et al., inhibitory subunit are important determinants of salt 1989). More recently, in the eukaryotic model system tolerance, cell wall integrity and cell cycle progression. Saccharomyces cerevisiae, alterations in the expression of We present several lines of evidence showing that several genes encoding signal transduction proteins have these disparate phenotypes are connected by the fact been shown to affect both intracellular ion homeostasis that Ppz regulates K+ transport. First, salt tolerance, and cell cycle, again suggesting a possible link between cell wall integrity and cell cycle phenotypes of Ppz these two highly regulated cellular processes. -

ZOOLOGY Animal Physiology Osmoregulation in Aquatic

Paper : 06 Animal Physiology Module : 27 Osmoregulation in Aquatic Vertebrates Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Neeta Sehgal Department of Zoology, University of Delhi Co-Principal Investigator: Prof. D.K. Singh Department of Zoology, University of Delhi Paper Coordinator: Prof. Rakesh Kumar Seth Department of Zoology, University of Delhi Content Writer: Dr Haren Ram Chiary and Dr. Kapinder Kirori Mal College, University of Delhi Content Reviewer: Prof. Neeta Sehgal Department of Zoology, University of Delhi 1 Animal Physiology ZOOLOGY Osmoregulation in Aquatic Vertebrates Description of Module Subject Name ZOOLOGY Paper Name Zool 006: Animal Physiology Module Name/Title Osmoregulation Module Id M27:Osmoregulation in Aquatic Vertebrates Keywords Osmoregulation, Active ionic regulation, Osmoconformers, Osmoregulators, stenohaline, Hyperosmotic, hyposmotic, catadromic, anadromic, teleost fish Contents 1. Learning Objective 2. Introduction 3. Cyclostomes a. Lampreys b. Hagfish 4. Elasmobranches 4.1. Marine elasmobranches 4.2. Fresh-water elasmobranches 5. The Coelacanth 6. Teleost fish 6.1. Marine Teleost 6.2. Fresh-water Teleost 7. Catadromic and anadromic fish 8. Amphibians 8.1. Fresh-water amphibians 8.2. Salt-water frog 9. Summary 2 Animal Physiology ZOOLOGY Osmoregulation in Aquatic Vertebrates 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you shall be able to • Learn about the major strategies adopted by different aquatic vertebrates. • Understand the osmoregulation in cyclostomes: Lamprey and Hagfish • Understand the mechanisms adopted by sharks and rays for osmotic regulation • Learn about the strategies to overcome water loss and excess salt concentration in teleosts (marine and freshwater) • Analyse the mechanisms for osmoregulation in catadromic and anadromic fish • Understand the osmotic regulation in amphibians (fresh-water and in crab-eating frog, a salt water frog). -

Excretory Products and Their Elimination

290 BIOLOGY CHAPTER 19 EXCRETORY PRODUCTS AND THEIR ELIMINATION 19.1 Human Animals accumulate ammonia, urea, uric acid, carbon dioxide, water Excretory and ions like Na+, K+, Cl–, phosphate, sulphate, etc., either by metabolic System activities or by other means like excess ingestion. These substances have to be removed totally or partially. In this chapter, you will learn the 19.2 Urine Formation mechanisms of elimination of these substances with special emphasis on 19.3 Function of the common nitrogenous wastes. Ammonia, urea and uric acid are the major Tubules forms of nitrogenous wastes excreted by the animals. Ammonia is the most toxic form and requires large amount of water for its elimination, 19.4 Mechanism of whereas uric acid, being the least toxic, can be removed with a minimum Concentration of loss of water. the Filtrate The process of excreting ammonia is Ammonotelism. Many bony fishes, 19.5 Regulation of aquatic amphibians and aquatic insects are ammonotelic in nature. Kidney Function Ammonia, as it is readily soluble, is generally excreted by diffusion across 19.6 Micturition body surfaces or through gill surfaces (in fish) as ammonium ions. Kidneys do not play any significant role in its removal. Terrestrial adaptation 19.7 Role of other necessitated the production of lesser toxic nitrogenous wastes like urea Organs in and uric acid for conservation of water. Mammals, many terrestrial Excretion amphibians and marine fishes mainly excrete urea and are called ureotelic 19.8 Disorders of the animals. Ammonia produced by metabolism is converted into urea in the Excretory liver of these animals and released into the blood which is filtered and System excreted out by the kidneys. -

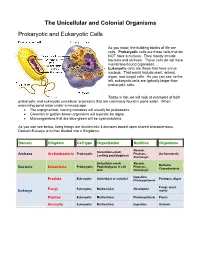

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic And

The Unicellular and Colonial Organisms Prokaryotic and Eukaryotic Cells As you know, the building blocks of life are cells. Prokaryotic cells are those cells that do NOT have a nucleus. They mostly include bacteria and archaea. These cells do not have membrane-bound organelles. Eukaryotic cells are those that have a true nucleus. That would include plant, animal, algae, and fungal cells. As you can see, to the left, eukaryotic cells are typically larger than prokaryotic cells. Today in lab, we will look at examples of both prokaryotic and eukaryotic unicellular organisms that are commonly found in pond water. When examining pond water under a microscope… The unpigmented, moving microbes will usually be protozoans. Greenish or golden-brown organisms will typically be algae. Microorganisms that are blue-green will be cyanobacteria. As you can see below, living things are divided into 3 domains based upon shared characteristics. Domain Eukarya is further divided into 4 Kingdoms. Domain Kingdom Cell type Organization Nutrition Organisms Absorb, Unicellular-small; Prokaryotic Photsyn., Archaeacteria Archaea Archaebacteria Lacking peptidoglycan Chemosyn. Unicellular-small; Absorb, Bacteria, Prokaryotic Peptidoglycan in cell Photsyn., Bacteria Eubacteria Cyanobacteria wall Chemosyn. Ingestion, Eukaryotic Unicellular or colonial Protozoa, Algae Protista Photosynthesis Fungi, yeast, Fungi Eukaryotic Multicellular Absorption Eukarya molds Plantae Eukaryotic Multicellular Photosynthesis Plants Animalia Eukaryotic Multicellular Ingestion Animals Prokaryotic Organisms – the archaea, non-photosynthetic bacteria, and cyanobacteria Archaea - Microorganisms that resemble bacteria, but are different from them in certain aspects. Archaea cell walls do not include the macromolecule peptidoglycan, which is always found in the cell walls of bacteria. Archaea usually live in extreme, often very hot or salty environments, such as hot mineral springs or deep-sea hydrothermal vents. -

Coral Reef Algae

Coral Reef Algae Peggy Fong and Valerie J. Paul Abstract Benthic macroalgae, or “seaweeds,” are key mem- 1 Importance of Coral Reef Algae bers of coral reef communities that provide vital ecological functions such as stabilization of reef structure, production Coral reefs are one of the most diverse and productive eco- of tropical sands, nutrient retention and recycling, primary systems on the planet, forming heterogeneous habitats that production, and trophic support. Macroalgae of an astonish- serve as important sources of primary production within ing range of diversity, abundance, and morphological form provide these equally diverse ecological functions. Marine tropical marine environments (Odum and Odum 1955; macroalgae are a functional rather than phylogenetic group Connell 1978). Coral reefs are located along the coastlines of comprised of members from two Kingdoms and at least over 100 countries and provide a variety of ecosystem goods four major Phyla. Structurally, coral reef macroalgae range and services. Reefs serve as a major food source for many from simple chains of prokaryotic cells to upright vine-like developing nations, provide barriers to high wave action that rockweeds with complex internal structures analogous to buffer coastlines and beaches from erosion, and supply an vascular plants. There is abundant evidence that the his- important revenue base for local economies through fishing torical state of coral reef algal communities was dominance and recreational activities (Odgen 1997). by encrusting and turf-forming macroalgae, yet over the Benthic algae are key members of coral reef communities last few decades upright and more fleshy macroalgae have (Fig. 1) that provide vital ecological functions such as stabili- proliferated across all areas and zones of reefs with increas- zation of reef structure, production of tropical sands, nutrient ing frequency and abundance. -

The Ecology of Dunaliella in High-Salt Environments Aharon Oren

Oren Journal of Biological Research-Thessaloniki (2014) 21:23 DOI 10.1186/s40709-014-0023-y REVIEW Open Access The ecology of Dunaliella in high-salt environments Aharon Oren Abstract Halophilic representatives of the genus Dunaliella, notably D. salina and D. viridis, are found worldwide in salt lakes and saltern evaporation and crystallizer ponds at salt concentrations up to NaCl saturation. Thanks to the biotechnological exploitation of D. salina for β-carotene production we have a profound knowledge of the physiology and biochemistry of the alga. However, relatively little is known about the ecology of the members of the genus Dunaliella in hypersaline environments, in spite of the fact that Dunaliella is often the main or even the sole primary producer present, so that the entire ecosystem depends on carbon fixed by this alga. This review paper summarizes our knowledge about the occurrence and the activities of different Dunaliella species in natural salt lakes (Great Salt Lake, the Dead Sea and others), in saltern ponds and in other salty habitats where members of the genus have been found. Keywords: Dunaliella, Hypersaline, Halophilic, Great Salt Lake, Dead Sea, Salterns Introduction salt adaptation. A number of books and review papers When the Romanian botanist Emanoil C. Teodoresco have therefore been devoted to the genus [5-7]. How- (Teodorescu) (1866–1949) described the habitat of the ever, the ecological aspects of the biology of Dunaliella new genus of halophilic unicellular algae Dunaliella,it are generally neglected. A recent monograph did not was known from salterns and salt lakes around the devote a single chapter to ecological aspects, and con- Mediterranean and the Black Sea [1-3]. -

JUDD W.S. Et. Al. (2002) Plant Systematics: a Phylogenetic Approach. Chapter 7. an Overview of Green

UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS An Overview of Green Plant Phylogeny he word plant is commonly used to refer to any auto- trophic eukaryotic organism capable of converting light energy into chemical energy via the process of photosynthe- sis. More specifically, these organisms produce carbohydrates from carbon dioxide and water in the presence of chlorophyll inside of organelles called chloroplasts. Sometimes the term plant is extended to include autotrophic prokaryotic forms, especially the (eu)bacterial lineage known as the cyanobacteria (or blue- green algae). Many traditional botany textbooks even include the fungi, which differ dramatically in being heterotrophic eukaryotic organisms that enzymatically break down living or dead organic material and then absorb the simpler products. Fungi appear to be more closely related to animals, another lineage of heterotrophs characterized by eating other organisms and digesting them inter- nally. In this chapter we first briefly discuss the origin and evolution of several separately evolved plant lineages, both to acquaint you with these important branches of the tree of life and to help put the green plant lineage in broad phylogenetic perspective. We then focus attention on the evolution of green plants, emphasizing sev- eral critical transitions. Specifically, we concentrate on the origins of land plants (embryophytes), of vascular plants (tracheophytes), of 1 UNCORRECTED PAGE PROOFS 2 CHAPTER SEVEN seed plants (spermatophytes), and of flowering plants dons.” In some cases it is possible to abandon such (angiosperms). names entirely, but in others it is tempting to retain Although knowledge of fossil plants is critical to a them, either as common names for certain forms of orga- deep understanding of each of these shifts and some key nization (e.g., the “bryophytic” life cycle), or to refer to a fossils are mentioned, much of our discussion focuses on clade (e.g., applying “gymnosperms” to a hypothesized extant groups. -

Claudins in the Renal Collecting Duct

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Review Claudins in the Renal Collecting Duct Janna Leiz 1,2 and Kai M. Schmidt-Ott 1,2,3,* 1 Department of Nephrology and Intensive Care Medicine, Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin, 12203 Berlin, Germany; [email protected] 2 Molecular and Translational Kidney Research, Max-Delbrück-Center for Molecular Medicine in the Helmholtz Association (MDC), 13125 Berlin, Germany 3 Berlin Institute of Health (BIH), 10178 Berlin, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-(0)30-450614671 Received: 22 October 2019; Accepted: 20 December 2019; Published: 28 December 2019 Abstract: The renal collecting duct fine-tunes urinary composition, and thereby, coordinates key physiological processes, such as volume/blood pressure regulation, electrolyte-free water reabsorption, and acid-base homeostasis. The collecting duct epithelium is comprised of a tight epithelial barrier resulting in a strict separation of intraluminal urine and the interstitium. Tight junctions are key players in enforcing this barrier and in regulating paracellular transport of solutes across the epithelium. The features of tight junctions across different epithelia are strongly determined by their molecular composition. Claudins are particularly important structural components of tight junctions because they confer barrier and transport properties. In the collecting duct, a specific set of claudins (Cldn-3, Cldn-4, Cldn-7, Cldn-8) is expressed, and each of these claudins has been implicated in mediating aspects of the specific properties of its tight junction. The functional disruption of individual claudins or of the overall barrier function results in defects of blood pressure and water homeostasis. In this concise review, we provide an overview of the current knowledge on the role of the collecting duct epithelial barrier and of claudins in collecting duct function and pathophysiology. -

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista

I Biology I Lecture Outline 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual - pages 95-115) Major Characteristics Algae 1. Cbaracteristics 2. Classification 3. Division Cblorophyta 4. Division Chrysophyta 5. Division Phaeopbyta 6. Division Rhodopbyta Protozoans 1. Characteristics 2. Classification 3. Class FlageUata 4. Class Sarcodina 5. Class Ciliata 6. Class Sporozoa I Biology I Lecture Notes 9 Kingdom Protista References (Textbook - pages 373-392, Lab Manual- pages 95-115) Major Characteristics I. Protists possess eukaryotic cells with well defined nuclei and organelles 2. Most are unicellular, however there are multi-cellularforms 3. They are diverse in their structure 4. They vary in size from microscope algae to kelp that can be over 100feet in length 5. They are diverse (like bacteria) in the way they meet their nutritional needs A . Some are photosynthetic like land plants - are autotrophic B. Some ingest theirfood like animals - heterotrophic by ingestion C. Some absorb theirfood like bacteria andfungi - heterotrophic by absorption D. One species - Euglena - is mixotrophic meaning that it is capable ofboth autotrophic and heterotrophic life styles. 6. Reproduction in Protists A. is usually asexual by mitosis B. sexual reproduction involves meiosis and spore formation and usualJy occurs only when environmental conditions are hostile C. spores are resistant and can withstand adverse conditions 7. Some protozoans form cysts - a type ofresting stage 8. Photosynthetic protists (mostly algae) are part ofplankton. Plankton are those organisms suspended infresh and marine waters that serve asfood for -- heterotrophic animals and other protists 9. There are diverse opinions on how to classify members ofthe Kingdom Protista.