Chapter 3. Public Space and the Material Legacies of Communism in Bucharest Duncan Light and Craig Young In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETEA GENERALA 01.07.2021.Cdr

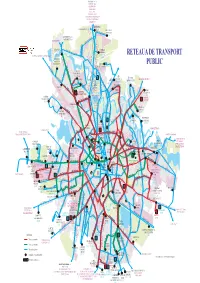

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 97 204 205 304 261 Sisesti BANEASA RETEAUA DE TRANSPORT R402 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 COMPLEX 112 205 261 97 131 261301 COMERCIAL Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti PUBLIC COLOSSEUM CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucurestii Noi Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 203 335 361 605 780 783 112 R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 Bd. Aerogarii R402 97 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 24 331R436 CFR Str. Alex. Serbanescu 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 DRIDU Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 65 86 112 135 243 Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Bd. Gloriei24 Str. Jiului 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Sos. Chitilei Poligrafiei PIATA PLATFORMA Bd. BucurestiiPajurei Noi 231 243 Str. Peris MEZES 780 783 INDUSTRIALA Str. PRESEI Str.Oi 3 45 65 86 331 243 3 45 382 PASAJ Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 3 41 243 PIPERA 382 DEPOUL R447 R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 i 65 86 97 243 16 36 COLENTINA 131105 203 205 261203 304 231 261 304 330 135 343 n tuz BUCURESTII NOI a R441 R442 R443 c 21 i CARTIER 605 tr 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 DEPOUL Bd. -

Cartare Infrastructura Etapa1.Pdf

Nr.contract: 829/22.07.2015 CARTARE INFRASTRUCTURĂ LA NIVELUL MUNICIPIULUI BUCUREȘTI Spații potențiale pentru activități culturale/ creative Beneficiar: Centrul de Proiecte Culturale al Municipiului București- ArCub Proiectant: UNIVERSITATEA DE ARHITECTURA ”ION MINCU” – CENTRUL DE CERCETARE, PROIECTARE, EXPERTIZĂ ŞI CONSULTING BUCUREŞTI UNIVERSITATEA DE ARHITECTURĂ ”ION MINCU” – CENTRUL DE CERCETARE, PROIECTARE, EXPERTIZĂ ŞI CONSULTING BUCUREŞTI Manager General: Prof. dr. arh. Emil Barbu Popescu Director: ec. Dana Racu Coordonator proiect: lect.dr.urb. Andreea Popa Colectiv de elaborare: prof.dr.arh. Tiberiu Florescu conf. dr. arh. Cerasella Craciun conf. dr. arh. Cristina Enache lect. dr . urb. Andreea Popa dr. arh. Catalina Ionita asist. dr. urb. Mihai Alexandru asist. dr. urb. peisag. Sorina Rusu asist. dr. urb. peisag. Andreea Bunea dr. urb. peisag. Irina Pata ms. urb. Nicolae Ionut Negrea urb. Corina Chirila st. arh. Ram Gretcu st. urb. peisag. Marin Gabi st. urb. Brastaviceanu Marilena 2 CUPRINS 1. DEFINIREA OBIECTIVELOR STUDIULUI ................................................................. 4 1.1. Contextul și problematica studiului ................................................................................ 4 1.2. Scopul și obiectivele studiului ........................................................................................ 6 1.3 Delimitarea zonei de studiu din București ...................................................................... 8 2. DISPUNERE ZONE CU POTENȚIAL LA NIVELUL MUNICIPIULUI BUCUREȘTI - Criterii -

Trasee De Noapte

PROGRAMUL DE TRANSPORT PENTRU RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE - TRASEE DE NOAPTE Plecari de la capete de Linia Nr Numar vehicule Nr statii TRASEU CAPETE lo traseu Lungime c 23 00:30 1 2 03:30 4 5 Prima Ultima Dus: Şos. Colentina, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. Ferdinand, Şos. Pantelimon, Str. Gǎrii Cǎţelu, Str. N 101 Industriilor, Bd. Basarabia, Bd. 1 Dus: Decembrie1918 0 2 2 0 2 0 0 16 statii Intors: Bd. 1 Decembrie1918, Bd. 18.800 m Basarabia, Str. Industriilor, Str. Gǎrii 88 Intors: Cǎţelu, Şos. Pantelimon, Bd. 16 statii Ferdinand, Şos. Mihai Bravu, Şos. 18.400 m Colentina. Terminal 1: Pasaj Colentina 00:44 03:00 Terminal 2: Faur 00:16 03:01 Dus: Piata Unirii , Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Universitatii, Bd. Carol I, Bd. Pache Protopopescu, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Str. Vatra Luminoasa, Bd. N102 Pierre de Coubertin, Sos. Iancului, Dus: Sos. Pantelimon 1 2 2 2 2 2 2 19 statii Intors: Sos. Pantelimon, Sos. Iancului, 8.400 m Bd. Pierre de Coubertin, Str. Vatra 88 Intors: Luminoasa, Sos. Mihai Bravu, Bd. 16 statii Pache Protopopescu, Bd. Carol I, 8.600 m Piata Universitatii, Bd. I. C. Bratianu, Piata Unirii. Terminal 1: Piata Unirii 2 23:30 04:40 Terminal 2: Granitul 22.55 04:40 Dus: Bd. Th. Pallady, Bd. Camil Ressu, Cal. Dudeşti, Bd. O. Goga, Str. Nerva Traian, Cal. Văcăreşti, Şos. Olteniţei, Str. Ion Iriceanu, Str. Turnu Măgurele, Str. Luică, Şos. Giurgiului, N103 Piaţa Eroii Revoluţiei, Bd. Pieptănari, us: Prelungirea Ferentari 0 2 1 0 2 0 0 24 statii Intors: Prelungirea Ferentari, , Bd. -

Lista Afiliati in Cadrul Programului "O Sansa Pentru Cuplurile Infertile" Fiv 2

LISTA AFILIATI IN CADRUL PROGRAMULUI "O SANSA PENTRU CUPLURILE INFERTILE" FIV 2 Nr. FARMACII Adresă Sector Telefon E-mail crt. 1 Dona 197 Str. Almas, nr. 2-8, Piata 16 Februarie 1 0372 407 197 [email protected] 2 Dona 235 Bd. Bucurestii Noi 62, lot 2 1 0372 407 235 [email protected] 3 Dona 60 Bd. Ion Mihalache nr. 168D 1 0372 407 060 [email protected] 4 Dona 33 Bd. Ion Mihalache, nr. 197 1 0372 407 033 [email protected] 5 Dona 17 Calea Dorobanti, nr. 102-110 1 0372 407 017 [email protected] 6 Dona 54 Str Hatmanul Arbore 15-19 1 0372 032 534 [email protected] 7 Dona 287 Bd. Magheru nr. 32-36 1 0372 401 287 [email protected] 8 Dona 396 Complex Comercial Piata Pajura, nr. 7 1 0372 401 828 [email protected] 9 Farmacaia Elexa Piata Charles de Gaulle 2, ap 2, Corp B 1 0728808570 [email protected] 10 Farmacia Medlife PharmaLife Calea Grivitei nr. 365 1 0735.300.990 [email protected] 11 Farmacia Pharma-Plant Baneasa Bd.Ficusului nr. 23 1 0749.039.541 [email protected] 12 Farmacia Pharma-Plant Titulescu Bld. Nicolae Titulescu nr. 39-49 1 0749.039.704 [email protected] 13 Catena Aerogarii B-dul Aerogarii nr.32, 1 0741.10.6893 [email protected] 14 Catena Grivita 234 Calea Grivitei nr.234, Bl.1, Sc.A, Ap.1, 1 0744.35.9281 [email protected] 15 Catena Titulescu B-dul Nicolae Titulescu nr.10, Bl. 20 , 1 0747.02.0577 [email protected] 16 Catena Ion Mihalache -Turda B-dul Ion Mihalache nr.113 , Bloc 11, 1 0743.00.4177 [email protected] 17 Catena Sala Palatului Str. -

Rahova – Uranus: Un „Cartier Dormitor”?

RAHOVA – URANUS: UN „CARTIER DORMITOR”? BOGDAN VOICU DANA CORNELIA NIŢULESCU ahova–Uranus este o zonă a oraşului Bucureşti situată aproape de centru, însă, ca multe alte cartiere, lipsită aproape complet de orice R viaţă culturală. Studiul de faţă se referă la reprezentările tinerilor din zonă asupra cartierului lor. Folosind date calitative, arătăm că tinerii bucureşteni din Rahova văd în mizerie, aglomeraţie, trafic principalele probleme ale oraşului şi ale zonei în care trăiesc. Investigarea reprezentărilor şi comportamentelor de consum cultural ale tinerilor din cartierul bucureştean Rahova–Uranus relevă caracteristica zonei de a fi, în principal, un „cartier-dormitor”. Oamenii par a veni aici doar ca să locuiască, fiind preocupaţi mai ales în a dormi, a mânca, şi a-şi îndeplini nevoile fiziologice. Materialul de faţă utilizează rezultatele unei cercetări despre modul în care tinerii din zona Rahova – Uranus îşi satisfac nevoia de cultură. Cercetarea, iniţiată şi finanţată de British Council, parte a unui proiect mai larg gestionat de Centrul Internaţional pentru Artă Contemporană1, a fost realizată în octombrie 2006, implicând interviuri semistructurate, cu 26 de tineri între 17 şi 35 de ani. În articolul de faţă ne propunem să contribuim la o mai bună cunoaştere a locuitorilor tineri din zona Rahova – Uranus, identificând nevoile lor de natură culturală, precum şi comportamentele de consum cultural. Ne propunem o descriere, o prezentare de tip documentar a realităţilor observate, explicaţiei şi interpretării fiindu-le alocat un spaţiu mai restrâns. Studiul are în centrul său culturalul nevoia de frumos, cu alte cuvinte acea versiune a culturii în sensul dat de ştiinţele umane2. Suntem interesaţi în ce măsură 1 Mulţumim British Council şi CIAC pentru acceptul de a publica acest material, care utilizează în bună măsură textul raportului de cercetare realizat. -

Retea Agentii Distributie Raiffeisen Acumulare

Lista agentii Raiffeisen Bank Reteaua de distributie a Fondului de pensii facultative Raiffeisen Acumulare administrat de catre Raiffeisen Asset Management Judet Localitate Nume Agentie Adresa completa Telefon fix Alba Alba Iulia Ag. Alba Piata Iuliu Maniu, nr. 4, loc. Alba Iulia, jud. Alba 0258.703.501- 0258.703.503 Alba Sebes Ag. Sebes Strada Lucian Blaga, nr. 47, loc. Sebes, jud. Alba 0258.703.661 - 0258.703.664 Arad Arad Ag. Arad Strada Andrei Saguna, nr. 1-3, loc. Arad, jud. Arad 0257.703.510 - 0257.703.533 Arad Arad Ag. Teatru Strada Unirii, nr. 1, loc. Arad, jud. Arad 0257.703.680 Arges Pitesti Ag. Arges Calea Craiovei, nr. 42, loc. Pitesti, jud. Arges 0248.703.500 - 0248.703.549 Arges Pitesti Ag. Pitesti 2 Piata Vasile Milea, A4, loc. Pitesti, jud. Arges 0248.703.823 - 0248.703.828 Bihor Marghita Ag. Marghita Strada Republicii, nr. 13, loc. Marghita, jud. Bihor 0259.703.601 - 0259.703.603 Bihor Oradea Ag. Vulturul Negru Piata Unirii, nr. 2-4, loc. Oradea, jud. Bihor 0259.703.641 - 0259.703.647 Bistrita Nasaud Bistrita Ag. Bistrita Strada Liviu Rebreanu, nr. 51, loc. Bistrita, jud. Bistrita-Nasaud 0263.703.500 - 0263.703.519 Braila Braila Ag. Braila Strada Calea Calarasilor, nr. 34, loc. Braila, jud. Braila 0239.703.500 - 0239.703.522 Brasov Brasov Ag. Brasov Strada Harmanului, nr. 24, loc. Brasov, jud. Brasov 0268.703.500 - 0268.703.554 Brasov Brasov Ag. Piata Sfatului Strada Sfatului, nr. 18, loc. Brasov, jud. Brasov 0268.703.620 - 0268.703.626 Brasov Fagaras Ag. Fagaras Strada Republicii, nr. -

Autobuze.Pdf

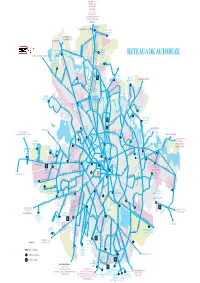

OTOPENI 780 783 OSTRATU R441 OTOPENI R442 PERIS R443 PISCU R444 GRUIU R446 R447 MICSUNESTII MARI R447B MOARA VLASIEI R448 SITARU 477 GREENFIELD STRAULESTI 204 304 203 204 Aleea PrivighetorilorJOLIE VILLE BANEASA 301 301 301 GREENFIELD 204 BUFTEA R436 PIATA PRESEI 304 131 Str. Jandarmeriei261 304 STRAULESTI Sos. Gh. Ionescu COMPLEX 261 BANEASA RETEAUA DE AUTOBUZE 204 205 304 Sisesti 205 131 261 335 BUFTEA GRADISTEA SITARU R402 R402 261 205 R402 R436 Bd. OaspetilorStr. Campinita 361 605 112 205 261 COMPLEX 131 261301 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti COMERCIAL CARTIER 231 Sos. Chitilei Bd. Bucu Sos. Straulesti R447 R447B R448 R477 COLOSSEUM 203 335 361 605 780 783 Bd.R441 R442 R443 R444HENRI R446 COANDA 231 112 Aerogarii R402 605 231 112 112 CARTIER 112 301 112 restii Noi DAMAROAIA 131 R436 335 231 Sos. Chitilei R402 331 R436 CFR 112 CONSTANTA CARTIER MERII PETCHII R409 112 Str. N. Caramfil R402 Bd. Laminorului AUTOBAZA ANDRONACHE 331 112 135 243 Str. Jiului Bd. NORDULUI112 301 382 Sos. Chitilei 605 Sos. 112Pipera 135 Poligrafiei 231 243 Str. Peris 780 783 331 PIATA Str.Oi 243 382 Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti 243 382 R447PRESEI R447BR448 R477 112 231 243 243 131 203 205 261 304 135 343 105 203 231 tuz CARTIER 261 304 330 361 605 231R441 361 R442 783 R443 R444 R446 Bd. Marasti GIULESTI-SARBI 162 R441 R442 R443 r a lo c i s Bd. Expozitiei231 330 r o a dronache 162 163 105 780 R444 R446t e R409 243 343 Str. Sportului a r 105 i CLABUCET R447 o v l F 381 R448 A . -

Noapte (Hartă)

ROND ODAII N117 N117 Bd. Gh. Ionescu Sisesti COMPLEX RETEAUA DE NOAPTE N118 COMERCIAL N117 N118 n BANEASA n Io es r. Io cu N118 St N113 d Bd. Bucurestii Noi e l N118 a Sos. Bucuresti Ploiesti B N118 r ad N113 N117 AUTOBAZA AUTOBAZA NORDULUI PIPERA Str. CoralilorN113 Str. Av. Serbanescu C.F.R. N118 CONSTANTA CARTIER Bd. Laminorului N119 BANEASA Bd. GlorieiN113 Sos. Chitilei N113 Sos. PiperaN119 PASAJ N118 N113 N117 N118 COLENTINA DEPOUL N101 N108 N123 BUCURESTII NOI a c DEPOUL DEPOUL s a e COLENTINA GIULESTI r o l F N119 . CARTIER l ColentinaN123 Cal. Giulesti a Sos. Fundeni 16 FEBRUARIE C Sos. N108 N110 N110 Bd. Ion N113 Cal. Grivitei N123 N101 N101 N117 N118 AUTOBAZA Mihalache N113 FLOREASCA Str. B Cal. Giulesti Bd. Lacul Tei N113 d N123 Doamna . N113 C N113 N108 o N123 n N118 N110 sN118 DEPOUL Ghica t ru VICTORIA c N119 to N101 N108 ri N113 lo Sos.Crangasi Sos. Colentina r N113 Sos. Stefan cel N118 N117 Mare N119 N113 BAICULUI N108 Cal. Grivitei N125 N119 N125 N125 N101 N125 Sos.Virtutii N N108 N110 N118 N123 108 Bd. N. Balcescu Str.N123 Viitorului N108Sos. Pantelimon N117 N117 Bd. Dacia Splaiul N117 N119 Bd. Ferdinand N117 N101 N101 Sos. Pantelimon Independentei N117 Calea MosilorN123 N101 N102 108 N113 N123 N113 N125 GRANITUL GRUP SCOLAR N N102 AUTO Bd. Pache ProtopopescuN113 N113 Sos. Vergului N115 N110 N102 Str. Vatra Luminoasa Sos. MihaiN102 N115 N116 AUTOBAZA DEPOUL Bd. Bd. Basarabia Sos. Garii Catelu N110 N118 Sos.Virtutii N116 Bd. -

Residential Areas with Deficient Access to Urban Parks in Bucharest – Priority Areas for Urban Rehabilitation

ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS and DEVELOPMENT Residential areas with deficient access to urban parks in Bucharest – priority areas for urban rehabilitation CRISTIAN IOJA, MARIA PATROESCU, LIDIA NICULITA, GABRIELA PAVELESCU, MIHAI NITA, ANNEMARIE IOJA Centre for Environmental Research and Impact Studies, University of Bucharest 1 Nicolae Balcescu Blvd., Sector 1, Bucharest, ROMANIA Abstract: - The paper emphasizes the real dimension of the urban parks surfaces deficit upon the built environment in Bucharest city. There were established residential area categories with deficient access to urban parks of high quality, considered to be priority intervention areas for urban rehabilitation (residential areas situated at more than 3 km from municipal importance parks, at more than 1 km from urban parks, residential areas with access to crowded parks, or with access to parks that have degraded endowments). Deficient access to Bucharest urban parks was correlated with the development projects of new residential quarters, being obviously the tendency of city suffocation under the pressure of constructed surfaces and agglomeration. Key-Words: - urban parks, residential areas, housing, Bucharest, rehabilitation priorities areas 1 Introduction residential areas was completed by a tendency of Green spaces represent an essential component in vertical development, initially through 4 floors large urban environments, to which they offer constru-ctions, then 9 and 10 floors, in the present numerous direct and indirect services (improving reaching 20 floors. These new residential surfaces environmental quality, recreation and leisure, accentuated the real deficit of public green spaces. climate amelioration etc.) [1], [2], [3]. Green spaces deficit is expressed through the degradation of housing conditions in urban environments [1], [2], [3], automatically determining an increase of housing costs [4], a degradation of the population’s health state [5], [6] and the appearance of social segregation problems [7], [8]. -

THE POST-COMMUNIST URBAN LANDSCAPE of BUCHAREST, ROMANIA HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors Committee of Texas State Universi

THE POST-COMMUNIST URBAN LANDSCAPE OF BUCHAREST, ROMANIA HONORS THESIS Presented to the Honors Committee of TexAs State University in PArtial Fulfillment of the Requirements for GrAduation in the Honors College by Nadine Oliver SAn Marcos, TexAs June 2014 THE POST - COMMUNIST URBAN LANDSCAPE OF BUCHAREST, ROMANIA Thesis Supervisor: ________________________________ Richard EArl, PhD DePArtment of GeogrAphy Approved: ____________________________________ HeAther C. GAlloway, PhD DeAn, Honors College ABSTRACT This thesis examines the formation of the post-communist urban landscape in Bucharest, Romania, with particular emphasis on the consequences of its transition from a centrally planned, communist economic and political structure to that of a free market system. The lasting legacy of failed communism and a painful, tumultous transition to a free enterprise economy has left Bucharest in a deteriorating state, despite its comparative wealth within the country. As a national capital, it is especially crucial that the urban landscape, inundated with outdated totalitarian ideology, be developed such that it expresses and encourages post-communist national identity. However, without efficient, centralized urban planning framework, the effects of post-communist economic liberalism and privatization have contributed to the creation of a chaotic and inefficient built urban landscape. This study traces the geographical dynamics of post-communist urban development in Bucharest through case studies, independent field research, and academic literature related to public infrastructure maintenance. The influences of failed public project initiatives, free market real estate development, and the socio-economic conditions of the city are examined. Theoretical and structural changes experienced by the city during and after its transition from communism and the current conditions and challenges of Bucharest are discussed in order to demonstrate the necessity of comprehensive, enforced urban planning policy in post-communist cities. -

DRUMUL - TABEREI IUT Lille 3 – Tourcoing 1Ère Année GU SOMMAIRE

2016 SADOUN Sofia TOURTE Emilie CHEVEREAU Doriane DRUMUL - TABEREI IUT Lille 3 – Tourcoing 1ère année GU SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………………………………..……………………………………………. P.3 I. Avant 1989 ... La naissance d'un emblème du communisme…………………………………….………………….. P.5 A) Une volonté communiste………………………………………………………………………………………………..P.5 B) Une mise en place progressive………………………………………………………………………………………..P.6 C) Vivre dans le quartier de Drumul Taberei avant 1989……………………………………………………..P.11 II.Après 1989, Drumul taberei un quartier en amélioration……………………………..……………………………….P.12 A) Une transition brutale……………………………………………………………………………………………………….P.12 B) Un quartier qui préserve son patrimoine et qui s’adapte à la société actuelle…………………..P.13 C) Drumul Taberei évolue grâce à l'appropriation par les habitants des espaces communs. …P.22 CONCLUSION……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..P.25 BIBLIOGRAPHIE…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… …..………P .26 2 INTRODUCTION Pays de l’Europe de l'est, la Roumanie fait partie de l'union européenne depuis 2007. Le pays a été pendant 40 ans sous un régime communiste. Le gouvernement avait pour ambition que sa capitale Bucarest devienne une puissance industrielle à rayonnement mondiale. Suite à cette industrialisation, le gouvernement va construire dans les périphéries mixtes intermédiaires de Bucarest des quartiers à vocation industrielle. Drumul Taberei notre quartier d'étude est l'un d'entre eux. Drumul taberei ou « camp de la route » est un quartier situé dans le secteur 6 au sud-ouest de Bucarest. Ce quartier possède une forte emprise historique, marqué par les différentes grandes périodes de l'histoire. Son nom rappelle la révolution de 1821 puisque Tudor Vladimirescu a construit son camp sur le quartier avant d’envahir la capitale. Sa trame est l'héritage du communisme. Ce quartier avait pour vocation de devenir un quartier ouvrier où cohabiteraient la fonction industrielle et résidentielle. -

Lista Farmacii Care Acorda Primul Ajutor Persoanelor Afectate De

Nr Furnizor ADRESA SEDIU SOCIAL/PUNCT DE LUCRU Sector 1 BELLADONNA 70 Bucureşti, b-dul Nicolae Balcescu, nr.16, sector 1 sector 1 2 BELLADONNA 8 Bucuresti,Bd. Ion Mihalachenr.106, sector 1 sector 1 3 CATENA FARMACIE - Grivita Bucuresti, Calea Grivitei nr.234, sector 1 sector 1 4 CATENA FARMACIE - Titulescu Bucuresti, Bd. Titulescu nr.12, sector 1 sector 1 5 CATENA FARMACIE - Plevnei Bucuresti, Calea Plevnei nr.122, sector 1 sector 1 6 CATENA FARMACIE - Dorobanti Bucuresti, Calea Dorobanti nr.152, sector 1 sector 1 7 CATENA FARMACIE - Grivita Bucuresti, Calea Grivitei nr.158, sector 1 sector 1 8 CATENA FARMACIE - Ion Mihalache 113 Bucuresti, Bd Ion Mihalache nr.113, bl.11, sector 1 sector 1 9 CATENA FARMACIE - Ion Mihalache 195 Bucuresti, Bd. Ion Mihalache nr.195, sector 1 sector 1 10 CATENA FARMACIE - Magheru Bucuresti, Bd. Magheru nr.41, sector 1 sector 1 11 CATENA FARMACIE - Stirbei Voda Bucuresti, Calea Stirbei Voda nr.17, sector 1 sector 1 12 CATENA FARMACIE -Aerogarii Bucuresti, Bd. Aerogarii nr.32, sector 1 sector 1 13 CATENA FARMACIE-Gura Ialomitei Bucuresti, Str. Gura Ialomitei nr.1, complex comercial, sector 1 sector 1 14 FARMACIA NR.118 Bucuresti, str. Ion Mihalache nr.98, bl.44A,sector 1 sector 1 15 FARMACIA NR.61 Bucuresti, Str. Sevastopol, sector1 1 sector 1 16 FARMACIA BELLADONNA 45 Bucuresti, calea Grivitei, nr.236, bl.H, sector 1 sector 1 17 FARMACIA BELLADONNA 50 Bucuresti, b-dul Aviatiei, nr.2, bloc 5A, sector 1 sector 1 18 FARMACIA BELLADONNA 55 Bucuresti, str.Washington, nr.2, sector 1 sector 1 19 FARMACIA BELLADONNA 56 Bucuresti, b-dul Camil Ressu, nr.41, sector 1 sector 1 20 FARMACIA BELLADONNA 8 Bucuresti, b-dul Ion Mihalache, nr.106, sector 1 sector 1 21 FARMACIA CATENA Mendeleev Bucuresti, str.