I KYOTO PROTOCOL, CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM (CDM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2017 As at June 30, 2017

Balance Sheet 2017 2016 Note (Rupees in thousand) EQUITY AND LIABILITIES CAPITAL AND RESERVES Authorised share capital - 950,000,000 (2016: 950,000,000) ordinary shares of Rs 10 each 9,500,000 9,500,000 - 50,000,000 (2016: 50,000,000) preference shares of Rs 10 each 500,000 500,000 10,000,000 10,000,000 Issued, subscribed and paid up share capital 438,119,118 (2016: 438,119,118) ordinary shares of Rs 10 each 5 4,381,191 4,381,191 Reserves 6 38,014,337 34,238,885 Un-appropriated profit 32,473,351 27,163,353 74,868,879 65,783,429 NON-CURRENT LIABILITIES Long term finances - secured 7 12,520,000 2,400,000 Long term deposits 8 79,441 77,813 Deferred liabilities 9 186,837 111,334 Deferred taxation 10 5,866,359 4,989,055 18,652,637 7,578,202 CURRENT LIABILITIES Trade and other payables 11 5,454,447 5,366,340 Accrued finance cost 12 217,204 52,931 Short term borrowings - secured 13 8,571,228 3,451,352 Current portion of non-current liabilities 14 523,778 1,150,921 Derivative financial instrument 15 48,056 - Provision for taxation 35,090 35,090 14,849,803 10,056,634 CONTINGENCIES AND COMMITMENTS 16 108,371,319 83,418,265 The annexed notes 1 to 47 form an integral part of these financial statements. Chief Executive 97 DG Cement Annual Report 2017 As At June 30, 2017 2017 2016 Note (Rupees in thousand) ASSETS NON-CURRENT ASSETS Property, plant and equipment 17 62,447,737 39,576,830 Intangible assets 18 - - Investments 19 18,564,054 12,947,976 Long term loans and deposits 20 58,844 57,938 81,070,635 52,582,744 CURRENT ASSETS Stores, spare parts -

Mrs. Naz Mansha Mian Raza Mansha

D. G. KHAN CEMENT COMPANY LIMITED PROFILE OF CANDIDATES CONSENTED TO CONTEST ELECTION OF DIRECTORS TO BE HELD IN ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING SCHEDULED ON OCTOBER 31, 2016 MRS. NAZ MANSHA Mrs. Naz Mansha has over 30 years’ experience as a Director on the Board of different companies. She has been associated with D. G. Khan Cement Company Limited (DGKCC) since 1994 and she is also a Director on the Board of Nishat Paper Products Company Limited, a subsidiary of DGKCC. MIAN RAZA MANSHA Mian Raza Mansha has more than 21 years diversified professional experience in various business sectors including Banking, Textile, Power, Cement, Insurance, Hotels, Properties, Natural Gas, Agriculture, Dairy etc. He received his Bachelor degree from the University of Pennsylvania, USA. Currently he is on the Board of: Director/Chief Executive Officer • D. G. Khan Cement Company Limited • Nishat Paper Products Co. Limited • Nishat Developers (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat (Gulberg) Hotels and Properties Ltd. Director • MCB Islamic Bank Limited • Nishat Hotels & Properties Limited • Sui Northern Gas Pipeline Limited • Adamjee Life Assurance Company Limited • MNET Services (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat (Raiwind) Hotels and Properties Ltd. D. G. KHAN CEMENT COMPANY LIMITED PROFILE OF CANDIDATES CONSENTED TO CONTEST ELECTION OF DIRECTORS TO BE HELD IN ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING SCHEDULED ON OCTOBER 31, 2016 • Nishat (Aziz Avenue) Hotels and Properties Ltd • Nishat Dairy (Pvt.) Limited • Euronet Pakistan (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat Agriculture Farming (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat Farm Supplies (Pvt.) Limited MR. KHALID NIAZ KHAWAJA Mr. Khalid Niaz Khawaja is a Fellow of Institute of Bankers, Pakistan. He has more than 44 years’ experience to work in different capacities in banking industry and CEO in one of the leading Leasing company. -

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. SCS Research | Market Report Committed to intelligent investing REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. July 1, 2020 REP-033 also log onto PSX Market Indexwww.jamapunji.pk 1-July-20 Current Net Net High Low Volume Indices Index Change Change % KSE 100 Index 34,889.41 34,924.29 34,409.87 (+467.49) +1.34% 196,705,840 KSE-30 Index 15,121.75 15,150.75 14,844.74 (+259.50) +1.72% 116,425,120 KMI-30 Index 56,561.65 56,661.86 54,995.25 (+1,566.40) +2.77% 130,754,297 All Share Index 24,959.44 24,996.90 24,660.31 (+299.13) +1.20% 315,035,920 KMI All Shares Index 17,441.70 17,475.04 17,069.10 (+372.60) +2.14% 186,744,837 NIT Pakistan Gateway 7,920.79 7,937.12 7,763.88 (+140.40) +1.80% 22,220,096 Index(NITPGI) UBL Pak. Enterprise 10,335.18 10,359.86 10,160.58 (+142.34) +1.40% 11,886,818 Index(UPP9) 30-June-20 Previous Net Net High Low Volume Indices Index Change Change % KSE 100 Index 34,421.92 34,424.61 34,146.05 (+240.12) +0.70% 124,361,318 KSE-30 Index 14,862.25 14,865.31 14,741.74 (+109.64) +0.74% 66,108,648 KMI-30 Index 54,995.25 55,215.22 54,840.77 (+27.53) +0.05% 66,155,990 All Share Index 24,660.31 24,699.82 24,474.85 (+149.48) +0.61% 223,159,558 KMI All Shares Index 17,069.10 17,126.05 17,017.82 (+14.23) +0.08% 98,992,840 NIT Pakistan Gateway 7,780.39 7,788.60 7,704.38 (+62.75) +0.81% 18,325,926 Index(NITPGI) UBL Pak. -

Newsletter Vol-10

1 2 2nd International Conferences Conference on Business, Corner Economics and Education Management Professor at School of Management University Sukkur IBA University hosted Sains, Malaysia, Dr. Mohammad Memon, 2nd International Conference on Chairman BISE, Hyderabad and Economics, Business, Education Management (ICEBM). The conference was attended by more than 300 participants from 40 National and International Universities and more than 100 papers were presented in the conference. Chief Guest of the conference, leader of the opposition national assembly of Pakistan, Syed Khursheed Ahmed Shah while speaking to audience said “As a politician I often worry about the declining economic condition of the country, because 40 years ago Pakistan’s economy was far more better than Saudi Arabia, Korea and Dr. Dawood Ashraf Senior Researcher at other countries” Islamic Research and Training Institute Bangor The key note speakers including, University, Saudi Arabia shed light on the Dr. Rosella Castellano Professor and economic reforms and changing economic Researcher at University of Macerata, trends and urged to promote culture of savings Italy, Dr. Ramayah Tharasamy to safeguard future. Penalists including, Dr. Ijaz Shafi Gillani Head of Gallup Pakistan, Dr. Mohammad Zaki Rashdi Director and Associate Dean at Iqra University, Dr. Tariq Kaleem, Executive Director at Institute of Charter Accountants Pakistan and Ms. Almas Abbas held brainstorming session on economic and educational reforms. On the concluding day prizes and souvenirs were distributed among the winners by the Registrar Sukkur IBA University Engr. Zahid Hussain Khand. 3 Conference on the Concept of Community Colleges in Pakistan Conference on the Concept of Dahar while addressing the conference said that Community Colleges in Pakistan was Sindh government is doing its utmost to overcome organized by Sukkur IBA University shortcomings in the education sector. -

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd

Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. SCS Research | Market Report Committed to intelligent investing REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. November 3, 2020 REP-033 also log onto Sales desk note… www.jamapunji.pk KSE100 closed at 40480.88 i.e. 1368.7 point plus. It made a high of 40499.64. US election results will sway international markets. Results will likely to be known tomorrow morning in Pakistan. Some economic indicators showing improvement despite negative media coverage. Monthly exports, monthly revenue etc showing some improvement. Monthly CPI too deceased slightly. PM announced package for industries on reducing electricity tariffs. This was actually reported yesterday in press. Yesterday KSE100 rebounded from ~39200. It can show resistance at 41863. Faisal Shaji REP033 www.scstrade.com Disclaimer: This report has been prepared by Standard Capital Securities (Pvt) Ltd. and is provided for information purposes only. The information and data on which this report is based are obtained from sources which we believe to be reliable but we do not guarantee that it is accurate or complete. Standard Capital Securities (Pvt) Ltd. accepts no responsibility whatsoever for any direct or indirect consequential loss arising from any use of this report or its contents. Investors are advised to take professional advice before making investments and Standard Capital Securities (Pvt) Ltd. does not take any responsibility and shall not be held liable for undue reliance on this report. This report may not be reproduced, distributed or published by any recipient for any purpose. Standard Capital Securities (Pvt.) Ltd. SCS Research | Market Report Committed to intelligent investing REP-033 also log onto www.jamapunji.pk Daily Market Summary Statistics Report…. -

D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited

D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited CONTENTS D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited Corporate Profile 2 Directors’ Report 3 Condensed Interim Balance Sheet 6 Condensed Interim Profit and Loss Account 8 Condensed Interim Cash Flow Statement 9 Condensed Interim Statement of Changes in Equity 10 Selected Notes to the Condensed Interim Financial Statements 11 D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited and its Subsidiary Directors’ Report 19 Condensed Interim Consolidated Balance Sheet 20 Condensed Interim Consolidated Profit and Loss Account 22 Condensed Interim Consolidated Cash Flow Statement 23 Condensed Interim Consolidated Statement of Changes in Equity 24 Selected Notes to the Condensed Interim Consolidated Financial Statements 25 1 D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited CORPORATE PROFILE Board of Directors Mrs. Naz Mansha Chairperson Mian Raza Mansha Chief Executive Mr. Khalid Qadeer Qureshi Mr. Zaka-ud-Din Mr. Muhammad Azam Mr. Inayat Ullah Niazi Chief Financial Officer Ms. Nabiha Shahnawaz Cheema Audit Committee Mr. Khalid Qadeer Qureshi Member/Chairman Mr. Muhammad Azam Member Ms. Nabiha Shahnawaz Cheema Member Company Secretary Mr. Khalid Mahmood Chohan Bankers Allied Bank Limited Askari Bank Limited Bank Alfalah Limited Citibank N.A. Deutsche Bank AG Dubai Islamic Bank Pakistan Limited Faysal Bank Limited Habib Bank Limited HSBC Limited MCB Bank Limited Meezan Bank Limited National Bank of Pakistan NIB Bank Limited Standard Chartered Bank (Pakistan) Limited The Bank of Punjab The Royal Bank of Scotland (Formerly ABN AMRO Bank (Pakistan) Limited) United Bank Limited Auditors KPMG Taseer Hadi & Co., Chartered Accountants Legal Advisor Mr. Shahid Hamid, Bar-at-Law Registered Office Nishat House, 53-A, Lawrence Road, Lahore-Pakistan UAN: 92-42-111-11- 33 - 33 92-42-6367812 Fax: 92-42-6367414 Email: [email protected] web site: www.dgcement.com Factory 1. -

List of Shareholders Without Cnic

D.G. KHAN CEMENT COMPANY LIMITED LIST OF SHAREHOLDERS WITHOUT CNIC Sr. No. DIVIDEND FOLIO NAME OF SHAREHOLDER TOTAL % of GROSS ZAKAT TAX NET DIVIDEND CINC NTN PASSPORT ADDRESS WARRANT NO. SHARES Shareholding DIVIDEND DEDUCTED DEDUCTED AMOUNT NO. NO. NO. 1 1006865066 000000000003 MR. JAVED AHMAD 118 0.00 590.00 30.00 103.00 457.00 C/O D.S. CORPORATION (PVT.) LTD. 20-K, GULBERG II, LAHORE 2 1006865067 000000000005 MR. MOHIB-UL-HAQ 366 0.00 1,830.00 - 320.00 1,510.00 APARTMENTS SF2, BLOCK-40 SEA VIEW APARTMENTS DEFENCE PHASE V KARACHI 3 1006865147 000000000867 MUHAMMAD ARSHAD FARUQUI 212 0.00 1,060.00 53.00 186.00 821.00 29/II, 16TH STREET KH-TANZEEM, PHASE 5, DEFENCE KARACHI. 4 1006865148 000000000888 MRS. SHAMIM AKHTER 6 0.00 30.00 2.00 5.00 23.00 12 SIND CLOTH MARKET M.A. JINNAH ROAD KARACHI. 5 1006865150 000000000943 YASMEEN AGHA 4,538 0.00 22,690.00 1,135.00 3,971.00 17,584.00 77/1, 12TH STREET, D.H.A., PHASE-VI KARACHI. 6 1006865151 000000000970 MISS SAIRA SHAFI 100 0.00 500.00 - 88.00 412.00 B-21, KDA SCHEME NO.1 OFF: SHAHRAH FAISAL KARACHI 7 1006865153 000000000984 MR. ISMAIL LALA 484 0.00 2,420.00 121.00 424.00 1,875.00 FLAT NO. 4, AZIZ MANSION 235 STRECHEN ROAD KARACHI.-74200 8 1006865154 000000000991 MR. IQBAL HUSSAIN SIDDIQUI 1 0.00 5.00 - 1.00 4.00 HOUSE NO. R-433, BLOCK NO. 18, F. -

D. G. Khan Cement Company Limited Profile of The

D. G. KHAN CEMENT COMPANY LIMITED PROFILE OF THE PERSONS CONSENTED TO CONTEST ELECTION OF DIRECTORS TO BE HELD IN ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING SCHEDULED ON OCTOBER 28, 2019 MRS. NAZ MANSHA Mrs. Naz Mansha has over 32 years’ experience as a Director on the Board of different companies. She has been associated with D. G. Khan Cement Company Limited (DGKCC) since 1994 and she is also a Chief Executive of Nishat Linen (Private) Limited, a subsidiary of Nishat Mills Limited and Director/Chief Executive of Emporium Properties (Pvt) Limited and Director on the Board of Golf View Land (Pvt) Limited. MIAN RAZA MANSHA Mian Raza Mansha has more than 23 years diversified professional experience in various business sectors including Banking, Textile, Power, Cement, Insurance, Hotels, Properties, Natural Gas, Agriculture, Dairy etc. He received his Bachelor degree from the University of Pennsylvania, USA. Currently he is on the Board of: Director/Chief Executive Officer • D. G. Khan Cement Company Limited • Nishat Paper Products Co. Limited • Nishat Developers (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat (Gulberg) Hotels and Properties Ltd. Director • MCB Islamic Bank Limited • Nishat Hotels & Properties Limited • MNET Services (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat (Raiwind) Hotels and Properties Ltd. • Nishat (Aziz Avenue) Hotels and Properties Ltd • Nishat Dairy (Pvt.) Limited • Euronet Pakistan (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat Agriculture Farming (Pvt.) Limited • Hyundai Nishat Motor (Pvt.) Limited • Nishat Agrotech Farms (Pvt) Limited MR. KHALID NIAZ KHAWAJA Mr. Khalid Niaz Khawaja is a Fellow of Institute of Bankers, Pakistan. He has more than 46 years’ experience to work in different capacities in banking industry and CEO in one of the leading Leasing company. -

OFF Market Transactions

Intermarket Securities Limited Member Karachi Stock Exchange OFF Market Transactions 27-Jun-18 (Sorted by Traded Value) Member code Member Name Members to Members Transaction Disc/Prem to (+) (-) Buying Member Name Selling Member Name Settlement date Symbol Company Turnover Rate Current Price Traded Val (PkRmn) Current Price 212 (169) Horizon Sec. Ltd Pearl Sec. Ltd 18-Jul-18 SMBL Summit Bank Limited 50,000,000 3.31 2.24 47.8% 165.50 8 (46) Optimus Capital Management (Pvt.) Ltd. Fortune Sec. Ltd 29-Jun-18 IBFL IbrahimFibres 1,495,000 62.90 60.79 3.5% 94.04 8 (46) Optimus Capital Management (Pvt.) Ltd. Fortune Sec. Ltd 29-Jun-18 SNBL Soneri Bank Ltd. 6,759,000 13.00 12.27 5.9% 87.87 8 (46) Optimus Capital Management (Pvt.) Ltd. Fortune Sec. Ltd 29-Jun-18 JSCL Jah. Siddiqui & Co. 2,741,500 19.00 18.83 0.9% 52.09 182 (135) Cassim Investments (Pvt) Ltd. Y. H. Sec. (Pvt) Ltd. 29-Jun-18 CSAP Cres.Steel 475,000 98.00 98.00 0.0% 46.55 27 (19) Habib Metropolitan Financial Services Ltd AKD Sec. Ltd 28-Jun-18 ATRL Attock Ref. 182,600 213.76 227.81 -6.2% 39.03 223 (84) Maan Sec. (Pvt) Ltd. Muhammad Munir Muhammad Ahmed Khanani Sec.29-Jun-18 (Pvt.) Ltd DCR Dolmen City Reit 1,000,000 35.00 13.00 169.2% 35.00 187 (13) SAZ Capital Sec. (Pvt.) Ltd. First Choice Sec. Ltd 28-Jun-18 TRG TRG Pakistan Ltd. 1,000,000 28.50 30.68 -7.1% 28.50 166 (84) Topline Sec. -

Climate Change Profile of Pakistan

Climate Change Profi le of Pakistan Catastrophic fl oods, droughts, and cyclones have plagued Pakistan in recent years. The fl ood killed , people and caused around billion in damage. The Karachi heat wave led to the death of more than , people. Climate change-related natural hazards may increase in frequency and severity in the coming decades. Climatic changes are expected to have wide-ranging impacts on Pakistan, a ecting agricultural productivity, water availability, and increased frequency of extreme climatic events. Addressing these risks requires climate change to be mainstreamed into national strategy and policy. This publication provides a comprehensive overview of climate change science and policy in Pakistan. About the Asian Development Bank ADB’s vision is an Asia and Pacifi c region free of poverty. Its mission is to help its developing member countries reduce poverty and improve the quality of life of their people. Despite the region’s many successes, it remains home to a large share of the world’s poor. ADB is committed to reducing poverty through inclusive economic growth, environmentally sustainable growth, and regional integration. Based in Manila, ADB is owned by members, including from the region. Its main instruments for helping its developing member countries are policy dialogue, loans, equity investments, guarantees, grants, and technical assistance. CLIMATE CHANGE PROFILE OF PAKISTAN ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK www.adb.org Prepared by: Qamar Uz Zaman Chaudhry, International Climate Technology Expert ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) © 2017 Asian Development Bank 6 ADB Avenue, Mandaluyong City, 1550 Metro Manila, Philippines Tel +63 2 632 4444; Fax +63 2 636 2444 www.adb.org Some rights reserved. -

IEE 2016 File No

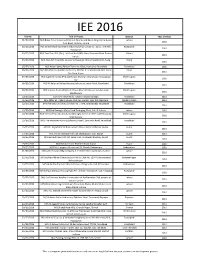

IEE 2016 File No. Title of Project District Year of Filing 01/IEE/2016 M/S Breez Frost Industries (Pvt) Ltd, (Stones and Beads Mfg,Co) Harbanse Lahore 2016 Pura Road, TajPura, Lahore 02/IEE/2016 M/s One the Mall (Commercial Building) Plot Survey No. 167/1, The Mall, Rawalpindi 2016 Rawalpindi 03/IEE/2016 M/S Zam Zam LPG, (Pvt), Ltd Chak No 3/WB, 6 km. Burewala Road District Vehari 2016 Vehari. 04/IEE/2016 M/S Abdullah Rice Mills. Mouza Kot Saisingh Chiniot road District Jhang. Jhang 2016 05/IEE/2016 M/S Amcon (pvt), Paradis Tower at,136/c, D-ground, Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 06/IEE/2016 M/S Medifarnecs (Harble medicene), Plot No. 9-D, Small Ind Estate. Feroz Kasur 2016 Pur Road, Kasur 07/IEE/2016 M/S Suprewe Farnes,(Pvt) Ltd Mouza Dholwan, Manawala, Farooqabad, Sheikhupura 2016 SKP 08/IEE/2016 M/S Al-Raheem Vallays Housing Scheme at Satian Road, Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 09/IEE/2016 M/S Seasons Foods (Pvt) Ltd, Mouza Mian Ali Fakiran, Safadar abad. Sheikhupura 2016 Sheikhupura 10/IEE/2016 M/S A.N Textile Mills , Satiana road Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 11/IEE/2016 M/S Akbar oil Traders Mouza Chak No.175/RB, Shak Kot, Nankana Nankana Sahib 2016 12/IEE/2016 M/S Mianwali LPG (Pvt) Ltd Chak No. 77/RB, Jarawnwala, Faisalabad Faisalabad 2016 13/IEE/2016 M/S Pak Packages (Ext), (Food Packaging Files), 9-S.I.E, Lahore Lahore 2016 14/IEE/2016 M/S Friends Petro Chamicals Ltd (Storage) 2.2-km off SKP road Ferozwala, Sheikhupura 2016 Sheikhupura. -

2011-12 Annual Report.Pdf

D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited ANNUAL REPORT 2012 D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited ♦ QUAID-E-AZAM ♦ MUHAMMAD ALI JINNAH “My message to you all is of hope, courage and confidence. Let us mobilize all our resources in a systematic and organized way and tackle the grave issues that confront us with grim determination and discipline worthy of a great nation. (Eid- ul-Azha Message to the Nation October 24, 1947) ANNUAL REPORT 2012 D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited (LATE) MR. ZAKA UD DIN DIRECTOR HE SHALL ALWAYS REMAIN IN OUR DEEPEST MEMORY FOR HIS DEDICATION, SINCERITY, HUMILITY AND INTEGRITY. ANNUAL REPORT 2012 D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited 2012 HIGHLIGHTS Improving efficiency in a difficult environment Extensive cost-cutting measures and good levels of business in the emerging markets Operating margins exceed the previous year's figures Solid demand for building materials in the emerging markets Reduction in finance cost through better cash flow planning Carbon credits under Kyoto Protocol of United Nation Cost pressure from energy and raw materials weighed on results Increase in net income and higher operating profits More investment in process optimization and alternate energy sources ANNUAL REPORT 2012 D.G. Khan Cement Company Limited Mission Statement To provide quality products to customers and explore new markets to promote/expand sales of the Company through good governance and foster a sound and dynamic team, so as to achieve optimum prices of products of the Company for sustainable and equitable growth and prosperity of the Company. Vision Statement To transform the Company into a modern and dynamic cement manufacturing company with qualified professionals and fully equipped to play a meaningful role on sustainable basis in the economy of Pakistan.