FINLEY, Nicholas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890 Richard P. Matthews Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Matthews, Richard P., "Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3808. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5692 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Richard P. Matthews for the Master of Arts in History presented 4 November, 1988. Title: Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier: East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington county, 1840 - 1890. APPROVED BY MEMBE~~~ THESIS COMMITTEE: David Johns n, ~on B. Dodds Michael Reardon Daniel O'Toole The evolution of the small towns that originated in Oregon's settlement communities remains undocumented in the literature of the state's history for the most part. Those .::: accounts that do exist are often amateurish, and fail to establish the social and economic links between Oregon's frontier towns to the agricultural communities in which they appeared. The purpose of the thesis is to investigate an early settlement community and the small town that grew up in its midst in order to better understand the ideological relationship between farmers and townsmen that helped shape Oregon's small towns. -

Whitman Mission

WHITMAN MISSION NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE WASHINGTON At the fur traders' Green River rendezvous that A first task in starting educational work was to Waiilatpu, the emigrants replenished their supplies perstitious Cayuse attacked the mission on November year the two men talked to some Flathead and Nez learn the Indians' languages. The missionaries soon from Whitman's farm before continuing down the 29 and killed Marcus Whitman, his wife, and 11 WHITMAN Perce and were convinced that the field was promis devised an alphabet and began to print books in Columbia. others. The mission buildings were destroyed. Of ing. To save time, Parker continued on to explore Nez Perce and Spokan on a press brought to Lapwai the survivors a few escaped, but 49, mostly women Oregon for sites, and Whitman returned east to in 1839. These books were the first published in STATION ON THE and children, were taken captive. Except for two MISSION recruit workers. Arrangements were made to have the Pacific Northwest. OREGON TRAIL young girls who died, this group was ransomed a Rev. Henry Spalding and his wife, Eliza, William For part of each year the Indians went away to month later by Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson's Waiilatpu, "the Place of the Rye Grass," is the Gray, and Narcissa Prentiss, whom Whitman mar the buffalo country, the camas meadows, and the When the Whitmans Bay Company. The massacre ended Protestant mis site of a mission founded among the Cayuse Indians came overland in 1836, the in 1836 by Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. As ried on February 18, 1836, assist with the work. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Eric G. Stewart Collection Inventory

Box Folder Folder Title Title l Description Paper Date 23 1 Alanson Hinman, 1895-1918 "Summons" Hillsboro Argus 11/5/1908 23 1 Reminisences of Alanson Hinman and Early Forest Grove 23 1 untitled article News Times 10/17/1918 23 1 3 untitled articles on the old Hinman building Hatchet 10/17, 24, 31/1895 23 1 partial Mt. View Cemetary plot index 23 2 Samuel Hughes, 1874-1895 Notecard: S. Hughes & Son, Dealers In Hardware,…Stoves and …Tinware Hatchet 7/18/1895 23 2 Samuel Hughes 1869 1870 1871 1872 23 2 "In studying the history of Forest Grove we need to take time…." 23 2 Advertisements: Hughes & Co. The Independent Hillsboro 1/12/1888 23 2 Notes 23 3 John Konrad Ihrig, 1992 Actual Color Photograph of man (Bill Ihrig) standing by Ihrig Road sign 23 3 Actual Business Card of Bill Ihrig Line Superintendent Consumers Power Inc. 23 3 PG 1 of actual typewritten letter to NT from Sandra Ihrig Dated 6/1/1992 23 3 PG 2 of actual typewritten letter to NT from Sandra Ihrig 23 3 The John Konrad Ihrig Family (1871-1941) Pg 1. (marked #1) 23 3 Page 2 of the above. (not marked) 23 3 Ihrig Line of descent (males) (marked #2) 23 3 2 Photos of Dr Holger Ihrig on a bike in front of Ihrig street sign (marked #3) 23 3 John Konrad Ihrig Obit (1871-1941) 23 3 Bessie Ann (nee Frost) Ihrig (1878 - 1946) wife of J.K.Ihrig. 23 3 Photo of John Konrad and Bessie Ann Ihrig (1898 Wedding Photo) 1898 23 3 Photo Portrait of John Konrad Ihrig Born Jan. -

JOSEPH L. MEEK the Wonderful Romance Which Gave Enchantment

JOSEPH L. MEEK The wonderful romance which gave enchantment to stories of adventure, hardship, daring deeds and suffering which were en countered by those who figured conspicuously, and with considerable fame, in the early settlement and claiming of Oregon can be told by a long list of courageous men and women. One of this list who can never be lost sight of for his fearlessness, courage and good words and humor is Joseph L. Meek, a mountain man and first Sheriff of the Provisional Government of old Oregon. Joseph L. Meek was born in Washington County, Virginia, in 1810, one year before the settlement of Astoria, and at the period when Congress was much interested in the question of its far western possessions and their boundaries. "Manifest destiny" seems to have raised him up with many other bold, hardy and fearless men guards and sentinels on the outposts of civilization-securing to the United States with comparative ease a vast extent of territory for which without them a long struggle with England would have taken place. Loyal and faithful historians can not exclude their names from honorable mention, and very prominent must appear the name of Joseph L. Meek, the Rocky Mountain hunter and trapper. Mr. Meek did not try to disguise the fact that he was a mountain man. He possibly did many things he should not have done, and left un done many things he should have done. Still, seeing "Uncle Joe" good humored, quiet, not undignified, a true citizen of the plains, one could never accuse him of any very bad qualities. -

MEN of CHAMPOEG Fly.Vtr,I:Ii.' F

MEN OF CHAMPOEG fly.vtr,I:ii.' f. I)oI,I,s 7_ / The Oregon Society of the National Society Daughters of the American Revolution is proud to reissue this volume in honor of all revolutionaryancestors, this bicentennialyear. We rededicate ourselves to theideals of our country and ofour society, historical, educational andpatriotic. Mrs. Herbert W. White, Jr. State Regent Mrs. Albert H. Powers State Bicentennial Chairman (r)tn of (]jjainpog A RECORD OF THE LIVES OF THE PIONEERS WHO FOUNDED THE OREGON GOVERNMENT By CAROLINE C. DOBBS With Illustrations /4iCLk L:#) ° COLD. / BEAVER-MONEY. COINED AT OREGON CITY, 1849 1932 METROPOLITAN PRESS. PUBLISHERS PORTLAND, OREGON REPRINTED, 1975 EMERALD VALLEY CRAFTSMEN COTTAGE GROVE, OREGON ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS MANY VOLUMES have been written on the history of the Oregon Country. The founding of the provisional government in 1843 has been regarded as the most sig- nificant event in the development of the Pacific North- west, but the individuals who conceived and carried out that great project have too long been ignored, with the result that the memory of their deeds is fast fading away. The author, as historian of Multnomah Chapter in Portland of the Daughters of the American Revolution under the regency of Mrs. John Y. Richardson began writing the lives of these founders of the provisional government, devoting three years to research, studying original sources and histories and holding many inter- views with pioneers and descendants, that a knowledge of the lives of these patriotic and far-sighted men might be preserved for all time. The work was completed under the regency of Mrs. -

Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: a Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-7-1996 Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: A Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory Katherine Louise Huit Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Huit, Katherine Louise, "Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: A Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory" (1996). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 5293. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.7166 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. THESIS APPROVAL The abstract and thesis of Katherine Louise Huit for the Master of Arts in History were presented May 7, 1996, and accepted by the thesis committee and the department. COMMITIEE APPROVALS: Tom Biolsi Re~entative of ;e Office of Graduate Studies DEPARTMENT APPROVAL: David John.Sor}{ Chair Department-of History AA*AAAAAAAAAAAAA****AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA**********AAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA ACCEPTED FOR PORTLAND STATE UNIVERSITY BY THE LIBRARY on za-/4?£ /<f9t;, ABSTRACT An abstract of the thesis of Katherine Louise Huit for the Master of Arts in History presented May 7, 1996. Title: Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: A Whig Appointee In A Democratic Territory. In 1846 negotiations between Great Britain and the United States resulted in the end of the Joint Occupancy Agreement and the Pacific Northwest became the property of the United States. -

Mountain Man” by Jim Hardee Historical Use of This Terminology Translation, “Mountaineer” Continued in Use Even After

Newsletter of the Jedediah Smith Society • University of the Pacific, Stockton, California FALL 2013 Historical Use of the Term “Mountain Man” By Jim Hardee Historical use of this terminology translation, “mountaineer” continued in use even after for those hearty souls who braved the heyday of the fur trade had passed. Rudolph F. Kurz, the Rocky Mountains in search a Swiss artist who lived among the frontiersmen on the of beaver is scarce prior to the Upper Missouri from 1846 to 1852, referred to a crew of waning days of the beaver trade. One of the earliest boatmen carrying buf falo hides down river to St. Louis as consistent uses of the phrase comes from George “Mountaineers, a name associated with many dangerous Frederick Ruxton’s fictional story,Life in the Far West, adventures, much painful endur ance, but also with much first published in 1848.1 Prior to that time, most sources romance and pleasure.”7 seem to prefer the term “mountaineer.” As late as 1837, In her introduction to Robert Newell’s Memo randa, Washington Irving gave that name to what he called a Dorothy 0. Johansen postulates the term “mountain man” totally different class of frontiersmen in the Adventures may have originated among the trappers themselves. of Captain Bonneville.2 These were undoubtedly the Those who had first come into the mountains with Henry/ same fellows referred to today as “mountain men.” Ashley brigades and served their apprentice days under Irving was not the first to use this nomenclature for the one of the successive partnership fur companies may trappers of the Rocky Mountains. -

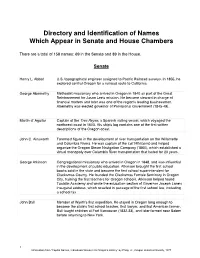

Inscribed Names in the Senate and House Chambers

Directory and Identification of Names Which Appear in Senate and House Chambers There are a total of 158 names: 69 in the Senate and 89 in the House. Senate Henry L. Abbot U.S. topographical engineer assigned to Pacific Railroad surveys. In 1855, he explored central Oregon for a railroad route to California. George Abernethy Methodist missionary who arrived in Oregon in 1840 as part of the Great Reinforcement for Jason Lee's mission. He became steward in charge of financial matters and later was one of the region's leading businessmen. Abernethy was elected governor of Provisional Government (1845-49). Martin d’ Aguilar Captain of the Tres Reyes, a Spanish sailing vessel, which voyaged the northwest coast in 1603. His ship's log contains one of the first written descriptions of the Oregon coast. John C. Ainsworth Foremost figure in the development of river transportation on the Willamette and Columbia Rivers. He was captain of the Lot Whitcomb and helped organize the Oregon Steam Navigation Company (1860), which established a virtual monopoly over Columbia River transportation that lasted for 20 years. George Atkinson Congregational missionary who arrived in Oregon in 1848, and was influential in the development of public education. Atkinson brought the first school books sold in the state and became the first school superintendent for Clackamas County. He founded the Clackamas Female Seminary in Oregon City, training the first teachers for Oregon schools. Atkinson helped found Tualatin Academy and wrote the education section of Governor Joseph Lane's inaugural address, which resulted in passage of the first school law, including a school tax. -

Conquest of the Algerian Landscape: Space, Myth, and Ideology in Algeria, 1830-1900 by Kristine Yoshihara Pg

Clio’s Scroll The Berkeley Undergraduate History Journal Vol. 13, No. 2 Spring 2012 Volume 13, No. 2, Spring 2012 Clio’s Scroll © 2010 Phi Alpha Theta Authors retain rights to individual essays Printed by Zee Zee Copy Cover Art: Photograph of Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, California, ca. 1891. Wikipedia Commons. STAFF 2011-2012 Editors-in-Chief Laura Kaufmann is a fourth-year history major specializing in eigh- teenth- and nineteenth-century British and European History. Her research interests focus on popular politics in late eighteenth-century Britain and the emergence of social and cultural identities in eigh- teenth- and nineteenth-century Britain. After graduating from UC Berkeley in May, she will continue her studies in Modern British and European History as a graduate student at the University of Oxford. Joanna Stedman is a fourth year history major, with a minor in public policy. She is primarily interested in the labor and social move- ments of early 20th century America. Associate Editors Cindy Kok is a third year history and political economy major. Her primary interest is in the history of 19th century Europe, particularly the cultural developments of Britain during the Industrial Revolution. Emily Rossi is a fourth year history and English major focusing on Modern Europe, with particular emphasis on World War I and World War II. She sings in the UC Women’s Chorale and loves to travel. Margaret Hatch is a fourth year, double majoring in legal studies and history, with an emphasis in Civil War and American Legal His- tory. She has been an editor for Clio’s Scroll for the past two years. -

Chapter 6 How Did the Cultural Diffusion of Westward Expansion Forever Impact America’S Identity?

MI OPEN BOOK PROJECT UnitedRevolution Through Reconstruction States History Amy Carlson, Alyson Klak, Erin Luckhardt, Joe Macaluso, Ben Pineda, Brandi Platte, Angela Samp The text of this book is licensed under a Creative Commons NonCommercial-ShareAlike (CC-BY-NC-SA) license as part of Michigan’s participation in the national #GoOpen movement. This is version 1.0.9 of this resource, released in August 2018 Information on the latest version and updates are available on the project homepage: http://textbooks.wmisd.org/dashboard.html Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike CC BY-NC-SA The Michigan Open Book About the Authors - US History - Revolution through Reconstruction Project Amy Carlson Thunder Bay Junior High Alpena Public Schools Amy has taught in Alpena Public Schools for many years. When not teaching or working on Project Manager: Dave Johnson, interactive Social Studies resources like this one she enjoys reading, hunting and fishing with Wexford-Missaukee Intermediate School her husband Erich, and sons Evan and Brady. District 8th Grade Team Editor - Rebecca J. Bush, Ottawa Area Intermediate School District Allyson Klak Authors Shepherd Middle School Shepherd Public Schools Amy Carlson - Alpena Public Schools Bio Forthcoming Allyson Klak - Shepherd Public Schools Erin Luckhardt - Boyne City Public Schools Ben Pineda - Haslett Public Schools Erin Luckhardt Brandi Platte - L’Anse Creuse Public Boyne City Middle School Schools Boyne City Public Schools Erin is an 8th grade social studies teacher at Boyne City Middle School in Boyne City, Angela Samp - Alpena Public Schools MI. She formerly served as the district’s technology coach when they were integrating their 1:1 iPad initiative. -

James D. Saules and the Enforcement of the Color Line in Oregon

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses Spring 5-16-2014 "Dangerous Subjects": James D. Saules and the Enforcement of the Color Line in Oregon Kenneth Robert Coleman Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Law and Race Commons, Political History Commons, and the Race, Ethnicity and Post- Colonial Studies Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Coleman, Kenneth Robert, ""Dangerous Subjects": James D. Saules and the Enforcement of the Color Line in Oregon" (2014). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1845. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1844 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. “Dangerous Subjects”: James D. Saules and the Enforcement of the Color Line in Oregon by Kenneth Robert Coleman A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: Katrine Barber, Chair Patricia Schechter David Johnson Darrell Millner Portland State Univesity 2014 © 2014 Kenneth Robert Coleman i Abstract In June of 1844, James D. Saules, a black sailor turned farmer living in Oregon’s Willamette Valley, was arrested and convicted for allegedly inciting Indians to violence against a settler named Charles E. Pickett. Three years earlier, Saules had deserted the United States Exploring Expedition, married a Chinookan woman, and started a freight business on the Columbia River.