Oregon Territorial Governor John Pollard Gaines: a Whig Appointee in a Democratic Territory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1988 Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890 Richard P. Matthews Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Matthews, Richard P., "Limited horizons on the Oregon frontier : East Tualatin Plains and the town of Hillsboro, Washington County, 1840-1890" (1988). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 3808. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.5692 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Richard P. Matthews for the Master of Arts in History presented 4 November, 1988. Title: Limited Horizons on the Oregon Frontier: East Tualatin Plains and the Town of Hillsboro, Washington county, 1840 - 1890. APPROVED BY MEMBE~~~ THESIS COMMITTEE: David Johns n, ~on B. Dodds Michael Reardon Daniel O'Toole The evolution of the small towns that originated in Oregon's settlement communities remains undocumented in the literature of the state's history for the most part. Those .::: accounts that do exist are often amateurish, and fail to establish the social and economic links between Oregon's frontier towns to the agricultural communities in which they appeared. The purpose of the thesis is to investigate an early settlement community and the small town that grew up in its midst in order to better understand the ideological relationship between farmers and townsmen that helped shape Oregon's small towns. -

Oregon Historic Trails Report Book (1998)

i ,' o () (\ ô OnBcox HrsroRrc Tnans Rpponr ô o o o. o o o o (--) -,J arJ-- ö o {" , ã. |¡ t I o t o I I r- L L L L L (- Presented by the Oregon Trails Coordinating Council L , May,I998 U (- Compiled by Karen Bassett, Jim Renner, and Joyce White. Copyright @ 1998 Oregon Trails Coordinating Council Salem, Oregon All rights reserved. No part of this document may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America. Oregon Historic Trails Report Table of Contents Executive summary 1 Project history 3 Introduction to Oregon's Historic Trails 7 Oregon's National Historic Trails 11 Lewis and Clark National Historic Trail I3 Oregon National Historic Trail. 27 Applegate National Historic Trail .41 Nez Perce National Historic Trail .63 Oregon's Historic Trails 75 Klamath Trail, 19th Century 17 Jedediah Smith Route, 1828 81 Nathaniel Wyeth Route, t83211834 99 Benjamin Bonneville Route, 1 833/1 834 .. 115 Ewing Young Route, 1834/1837 .. t29 V/hitman Mission Route, 184l-1847 . .. t4t Upper Columbia River Route, 1841-1851 .. 167 John Fremont Route, 1843 .. 183 Meek Cutoff, 1845 .. 199 Cutoff to the Barlow Road, 1848-1884 217 Free Emigrant Road, 1853 225 Santiam Wagon Road, 1865-1939 233 General recommendations . 241 Product development guidelines 243 Acknowledgements 241 Lewis & Clark OREGON National Historic Trail, 1804-1806 I I t . .....¡.. ,r la RivaÌ ï L (t ¡ ...--."f Pðiräldton r,i " 'f Route description I (_-- tt |". -

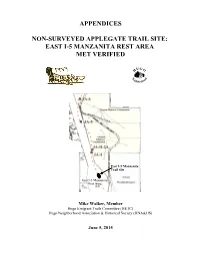

Appendices Non-Surveyed Applegate Trail Site: East I

APPENDICES NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED Mike Walker, Member Hugo Emigrant Trails Committee (HETC) Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HNA&HS) June 5, 2015 NON-SURVEYED APPLEGATE TRAIL SITE: EAST I-5 MANZANITA REST AREA MET VERIFIED APPENDICES Appendix A. Hugo Neighborhood Association & Historical Society (HuNAHS) Standards for All Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix B. HuNAHS’ Policy for Document Verification & Reliability of Evidence Appendix C. HETC’s Standards: Emigrant Trail Inventories and Decisions Appendix D1. Pedestrian Survey of Stockpile Site South of Chancellor Quarry in the I-5 Jumpoff Joe-Glendale Project, Josephine County (separate web page) Appendix D2. Subsurface Reconnaissance of the I-5 Chancellor Quarry Stockpile Project, and Metal Detector Survey Within the George and Mary Harris 1854 - 55 DLC (separate web page) Appendix D3. May 18, 2011 Email/Letter to James Black, Planner, Josephine County Planning Department (separate web page) Appendix D4. The Rogue Indian War and the Harris Homestead Appendix D5. Future Studies Appendix E. General Principles Governing Trail Location & Verification Appendix F. Cardinal Rules of Trail Verification Appendix G. Ranking the Reliability of Evidence Used to Verify Trial Location Appendix H. Emigrant Trail Classification Categories Appendix I. GLO Surveyors Lake & Hyde Appendix J. Preservation Training: Official OCTA Training Briefings Appendix K. Using General Land Office Notes And Maps To Relocate Trail Related Features Appendix L1. Oregon Donation Land Act Appendix L2. Donation Land Claim Act Appendix M1. Oregon Land Survey, 1851-1855 Appendix M2. How Accurate Were the GLO Surveys? Appendix M3. Summary of Objects and Data Required to Be Noted In A GLO Survey Appendix M4. -

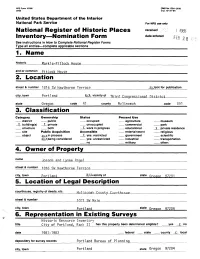

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Exp. 10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received r3 ! I985 Inventory—Nomination Form oawemereudate entered FEB ? £« \j See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections____________________________________ 1. Name historic Markle-Pittock House and or common pjttock House 2. Location street & number 1816 SW Hawthorne Terrace for publication city, town Portland state Oregon code 41 county Multnomah code 051 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied commercial park structure both _ X_ work in progress educational X private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object -j^t£ in process _ X_ yes: restricted government scientific 4^, being considered _ yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name and I ynne Angel street & number 1fl16 S y Havithnrne Tprrar.e city, town Portland JL/Avicinity of state QreaQn 07201 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Multnornah County Courthosue street & number m?1 SW Main city, town Portland state Qreaon 972Q4 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Historic Resource Inventory title City Of Portland, Rank II has this property been determined eligible? yes X no date 1981-1983 federal state county local depository for survey records Portland Bureau of Planning__ city, town Portland state Oregon 97204 7. Description Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered _X_ original site -Xgood ruins _X_ altered moved date N/A fair unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The Markle-Pittock House, whose construction was begun in 1888, was once considered the largest and most prominently sited residence in the city. -

Historical Overview

HISTORIC CONTEXT STATEMENT The following is a brief history of Oregon City. The intent is to provide a general overview, rather than a comprehensive history. Setting Oregon City, the county seat of Clackamas County, is located southeast of Portland on the east side of the Willamette River, just below the falls. Its unique topography includes three terraces, which rise above the river, creating an elevation range from about 50 feet above sea level at the riverbank to more than 250 feet above sea level on the upper terrace. The lowest terrace, on which the earliest development occurred, is only two blocks or three streets wide, but stretches northward from the falls for several blocks. Originally, industry was located primarily at the south end of Main Street nearest the falls, which provided power. Commercial, governmental and social/fraternal entities developed along Main Street north of the industrial area. Religious and educational structures also appeared along Main Street, but tended to be grouped north of the commercial core. Residential structures filled in along Main Street, as well as along the side and cross streets. As the city grew, the commercial, governmental and social/fraternal structures expanded northward first, and with time eastward and westward to the side and cross streets. Before the turn of the century, residential neighborhoods and schools were developing on the bluff. Some commercial development also occurred on this middle terrace, but the business center of the city continued to be situated on the lower terrace. Between the 1930s and 1950s, many of the downtown churches relocated to the bluff as well. -

Whitman Mission

WHITMAN MISSION NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE WASHINGTON At the fur traders' Green River rendezvous that A first task in starting educational work was to Waiilatpu, the emigrants replenished their supplies perstitious Cayuse attacked the mission on November year the two men talked to some Flathead and Nez learn the Indians' languages. The missionaries soon from Whitman's farm before continuing down the 29 and killed Marcus Whitman, his wife, and 11 WHITMAN Perce and were convinced that the field was promis devised an alphabet and began to print books in Columbia. others. The mission buildings were destroyed. Of ing. To save time, Parker continued on to explore Nez Perce and Spokan on a press brought to Lapwai the survivors a few escaped, but 49, mostly women Oregon for sites, and Whitman returned east to in 1839. These books were the first published in STATION ON THE and children, were taken captive. Except for two MISSION recruit workers. Arrangements were made to have the Pacific Northwest. OREGON TRAIL young girls who died, this group was ransomed a Rev. Henry Spalding and his wife, Eliza, William For part of each year the Indians went away to month later by Peter Skene Ogden of the Hudson's Waiilatpu, "the Place of the Rye Grass," is the Gray, and Narcissa Prentiss, whom Whitman mar the buffalo country, the camas meadows, and the When the Whitmans Bay Company. The massacre ended Protestant mis site of a mission founded among the Cayuse Indians came overland in 1836, the in 1836 by Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. As ried on February 18, 1836, assist with the work. -

Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 1-1-2011 The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 Cessna R. Smith Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Cessna R., "The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861" (2011). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 258. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.258 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. The Pursuit of Commerce: Agricultural Development in Western Oregon, 1825-1861 by Cessna R. Smith A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Thesis Committee: William L. Lang, Chair David A. Horowitz David A. Johnson Barbara A. Brower Portland State University ©2011 ABSTRACT This thesis examines how the pursuit of commercial gain affected the development of agriculture in western Oregon’s Willamette, Umpqua, and Rogue River Valleys. The period of study begins when the British owned Hudson’s Bay Company began to farm land in and around Fort Vancouver in 1825, and ends in 1861—during the time when agrarian settlement was beginning to expand east of the Cascade Mountains. Given that agriculture -

Title: the Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher's Guide of 20Fh Century Physics

REPORT NSF GRANT #PHY-98143318 Title: The Distribution of an Illustrated Timeline Wall Chart and Teacher’s Guide of 20fhCentury Physics DOE Patent Clearance Granted December 26,2000 Principal Investigator, Brian Schwartz, The American Physical Society 1 Physics Ellipse College Park, MD 20740 301-209-3223 [email protected] BACKGROUND The American Physi a1 Society s part of its centennial celebration in March of 1999 decided to develop a timeline wall chart on the history of 20thcentury physics. This resulted in eleven consecutive posters, which when mounted side by side, create a %foot mural. The timeline exhibits and describes the millstones of physics in images and words. The timeline functions as a chronology, a work of art, a permanent open textbook, and a gigantic photo album covering a hundred years in the life of the community of physicists and the existence of the American Physical Society . Each of the eleven posters begins with a brief essay that places a major scientific achievement of the decade in its historical context. Large portraits of the essays’ subjects include youthful photographs of Marie Curie, Albert Einstein, and Richard Feynman among others, to help put a face on science. Below the essays, a total of over 130 individual discoveries and inventions, explained in dated text boxes with accompanying images, form the backbone of the timeline. For ease of comprehension, this wealth of material is organized into five color- coded story lines the stretch horizontally across the hundred years of the 20th century. The five story lines are: Cosmic Scale, relate the story of astrophysics and cosmology; Human Scale, refers to the physics of the more familiar distances from the global to the microscopic; Atomic Scale, focuses on the submicroscopic This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government. -

“We'll All Start Even”

Gary Halvorson, Oregon State Archives Gary Halvorson, Oregon State “We’ll All Start Even” White Egalitarianism and the Oregon Donation Land Claim Act KENNETH R. COLEMAN THIS MURAL, located in the northwest corner of the Oregon State Capitol rotunda, depicts John In Oregon, as in other parts of the world, theories of White superiority did not McLoughlin (center) of the Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) welcoming Presbyterian missionaries guarantee that Whites would reign at the top of a racially satisfied world order. Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding to Fort Vancouver in 1836. Early Oregon land bills were That objective could only be achieved when those theories were married to a partly intended to reduce the HBC’s influence in the region. machinery of implementation. In America during the nineteenth century, the key to that eventuality was a social-political system that tied economic and political power to land ownership. Both the Donation Land Claim Act of 1850 and the 1857 Oregon Constitution provision barring Blacks from owning real Racist structures became ingrained in the resettlement of Oregon, estate guaranteed that Whites would enjoy a government-granted advantage culminating in the U.S. Congress’s passing of the DCLA.2 Oregon’s settler over non-Whites in the pursuit of wealth, power, and privilege in the pioneer colonists repeatedly invoked a Jacksonian vision of egalitarianism rooted in generation and each generation that followed. White supremacy to justify their actions, including entering a region where Euro-Americans were the minority and — without U.S. sanction — creating a government that reserved citizenship for White males.3 They used that govern- IN 1843, many of the Anglo-American farm families who immigrated to ment not only to validate and protect their own land claims, but also to ban the Oregon Country were animated by hopes of generous federal land the immigration of anyone of African ancestry. -

Bush House Today Lies Chiefly in Its Rich, Unaltered Interior,Rn Which Includes Original Embossed French Wall Papers, Brass Fittings, and Elaborate Woodwork

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Oregon COUNTTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Mari on INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries — complete applica#ie\s&ctipns) / \ ' •• &•••» JAN 211974 COMMON: /W/' .- ' L7 w G I 17 i97«.i< ——————— Bush (Asahel) House —— U^ ——————————— AND/OR HISTORIC: \r«----. ^ „. I.... ; „,. .....,.„„.....,.,.„„,„,..,.,..,..,.,, , ,, . .....,,,.,,,M,^,,,,,,,,M,MM^;Mi,,,,^,,p'K.Qic:r,£: 'i-; |::::V^^:iX.::^:i:rtW^:^ :^^ Sii U:ljif&:ii!\::T;:*:WW:;::^^ STREET AND NUMBER: "^s / .•.-'.••-' ' '* ; , X •' V- ; '"."...,, - > 600 Mission Street s. F. W J , CITY OR TOWN: Oregon Second Congressional Dist. Salem Representative Al TJllman STATE CODE COUNT ^ : CO D E Oreeon 97301 41 Marien Q47 STATUS ACCESSIBLE CATEGORY OWNERSHIP (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC r] District |t] Building SO Public Public Acquisit on: E Occupied Yes: r-, n . , D Restricted G Site Q Structure D Private Q ' n Process ( _| Unoccupied -j . —. _ X~l Unrestricted [ —[ Object | | Both [ | Being Consider ea Q Preservation work ^~ ' in progress ' — I PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) \ | Agricultural | | Government | | Park [~] Transportation l~l Comments | | Commercial CD Industrial | | Private Residence G Other (Specify) Q Educational d] Military Q Religious [ | Entertainment GsV Museum QJ] Scientific ...................... OWNER'S NAME: Ul (owner proponent of nomination) P ) ———————City of Salem————————————————————————————————————————— - ) -

Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Churches of Christ Heritage Center Jerry Rushford Center 1-1-1998 Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882 Jerry Rushford Pepperdine University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center Part of the Christianity Commons Recommended Citation Rushford, Jerry, "Christians on the Oregon Trail: Churches of Christ and Christian Churches in Early Oregon, 1842-1882" (1998). Churches of Christ Heritage Center. Item 5. http://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/heritage_center/5 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Jerry Rushford Center at Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Churches of Christ Heritage Center by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CHRISTIANS About the Author ON THE Jerry Rushford came to Malibu in April 1978 as the pulpit minister for the University OREGON TRAIL Church of Christ and as a professor of church history in Pepperdine’s Religion Division. In the fall of 1982, he assumed his current posi The Restoration Movement originated on tion as director of Church Relations for the American frontier in a period of religious Pepperdine University. He continues to teach half time at the University, focusing on church enthusiasm and ferment at the beginning of history and the ministry of preaching, as well the nineteenth century. The first leaders of the as required religion courses. movement deplored the numerous divisions in He received his education from Michigan the church and urged the unity of all Christian College, A.A. -

Report on the History of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn

Report on the History of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn By David Alan Johnson Professor, Portland State University former Managing Editor (1997-2014), Pacific Historical Review Quintard Taylor Emeritus Professor and Scott and Dorothy Bullitt Professor of American History. University of Washington Marsha Weisiger Julie and Rocky Dixon Chair of U.S. Western History, University of Oregon In the 2015-16 academic year, students and faculty called for renaming Deady Hall and Dunn Hall, due to the association of Matthew P. Deady and Frederick S. Dunn with the infamous history of race relations in Oregon in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. President Michael Schill initially appointed a committee of administrators, faculty, and students to develop criteria for evaluating whether either of the names should be stripped from campus buildings. Once the criteria were established, President Schill assembled a panel of three historians to research the history of Deady and Dunn to guide his decision-making. The committee consists of David Alan Johnson, the foremost authority on the history of the Oregon Constitutional Convention and author of Founding the Far West: California, Oregon, Nevada, 1840-1890 (1992); Quintard Taylor, the leading historian of African Americans in the U.S. West and author of several books, including In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (1998); and Marsha Weisiger, author of several books, including Dreaming of Sheep in Navajo Country (2009). Other historians have written about Matthew Deady and Frederick Dunn; although we were familiar with them, we began our work looking at the primary sources—that is, the historical record produced by Deady, Dunn, and their contemporaries.