In-Vivo Analysis of Sternal Angle, Sternal and Sternocostal Kinematics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Diapositiva 1

Thoracic Cage and Thoracic Inlet Professor Dr. Mario Edgar Fernández. Parts of the body The Thorax Is the part of the trunk betwen the neck and abdomen. Commonly the term chest is used as a synonym for thorax, but it is incorrect. Consisting of the thoracic cavity, its contents, and the wall that surrounds it. The thoracic cavity is divided into 3 compartments: The central mediastinus. And the right and left pulmonary cavities. Thoracic Cage The thoracic skeleton forms the osteocartilaginous thoracic cage. Anterior view. Thoracic Cage Posterior view. Summary: 1. Bones of thoracic cage: (thoracic vertebrae, ribs, and sternum). 2. Joints of thoracic cage: (intervertebral joints, costovertebral joints, and sternocostal joints) 3. Movements of thoracic wall. 4. Thoracic cage. Thoracic apertures: (superior thoracic aperture or thoracic inlet, and inferior thoracic aperture). Goals of the classes Identify and describe the bones of the thoracic cage. Identify and describe the joints of thoracic cage. Describe de thoracic cage. Describe the thoracic inlet and identify the structures passing through. Vertebral Column or Spine 7 cervical. 12 thoracic. 5 lumbar. 5 sacral 3-4 coccygeal Vertebrae That bones are irregular, 33 in number, and received the names acording to the position which they occupy. The vertebrae in the upper 3 regions of spine are separate throughout the whole of life, but in sacral anda coccygeal regions are in the adult firmly united in 2 differents bones: sacrum and coccyx. Thoracic vertebrae Each vertebrae consist of 2 essential parts: An anterior solid segment: vertebral body. The arch is posterior an formed of 2 pedicles, 2 laminae supporting 7 processes, and surrounding a vertebral foramen. -

The Structure and Function of Breathing

CHAPTERCONTENTS The structure-function continuum 1 Multiple Influences: biomechanical, biochemical and psychological 1 The structure and Homeostasis and heterostasis 2 OBJECTIVE AND METHODS 4 function of breathing NORMAL BREATHING 5 Respiratory benefits 5 Leon Chaitow The upper airway 5 Dinah Bradley Thenose 5 The oropharynx 13 The larynx 13 Pathological states affecting the airways 13 Normal posture and other structural THE STRUCTURE-FUNCTION considerations 14 Further structural considerations 15 CONTINUUM Kapandji's model 16 Nowhere in the body is the axiom of structure Structural features of breathing 16 governing function more apparent than in its Lung volumes and capacities 19 relation to respiration. This is also a region in Fascla and resplrstory function 20 which prolonged modifications of function - Thoracic spine and ribs 21 Discs 22 such as the inappropriate breathing pattern dis- Structural features of the ribs 22 played during hyperventilation - inevitably intercostal musculature 23 induce structural changes, for example involving Structural features of the sternum 23 Posterior thorax 23 accessory breathing muscles as well as the tho- Palpation landmarks 23 racic articulations. Ultimately, the self-perpetuat- NEURAL REGULATION OF BREATHING 24 ing cycle of functional change creating structural Chemical control of breathing 25 modification leading to reinforced dysfunctional Voluntary control of breathing 25 tendencies can become complete, from The autonomic nervous system 26 whichever direction dysfunction arrives, for Sympathetic division 27 Parasympathetic division 27 example: structural adaptations can prevent NANC system 28 normal breathing function, and abnormal breath- THE MUSCLES OF RESPIRATION 30 ing function ensures continued structural adap- Additional soft tissue influences and tational stresses leading to decompensation. -

Copyrighted Material

C01 10/31/2017 11:23:53 Page 1 1 1 The Normal Anatomy of the Neck David Bainbridge Introduction component’ of the neck is a common site of pathology, and the diverse forms of neck The neck is a common derived characteristic disease reflect the sometimes complex and of land vertebrates, not shared by their aquatic conflicting regional variations and functional ancestors. In fish, the thoracic fin girdle, the constraints so evident in this region [2]. precursor of the scapula, coracoid and clavi- Unlike the abdomen and thorax, there is no cle, is frequently fused to the caudal aspect of coelomic cavity in the neck, yet its ventral part the skull. In contrast, as vertebrates emerged is taken up by a relatively small ‘visceral on to the dry land, the forelimb separated from compartment’, containing the larynx, trachea, the head and the intervening vertebrae speci- oesophagus and many important vessels, alised to form a relatively mobile region – the nerves and endocrine glands. However, I neck – to allow the head to be freely steered in will not review these structures, as they do many directions. not represent an extension of the equine ‘back’ With the exception of the tail, the neck in the same way that the more dorsal locomo- remains the most mobile region of the spinal tor region does. column in modern-day horses. It permits a wide range of sagittal plane flexion and exten- sion to allow alternating periods of grazing Cervical Vertebrae 3–7 and predator surveillance, as well as frontal plane flexion to allow the horizon to be scan- Almost all mammals, including the horse, ned, and rotational movement to allow possess seven cervical vertebrae, C1 to C7 nuisance insects to be flicked off. -

Part 1 the Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3

ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 1 Part 1 The Thorax ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 2 ECA1 7/18/06 6:30 PM Page 3 Surface anatomy and surface markings The experienced clinician spends much of his working life relating the surface anatomy of his patients to their deep structures (Fig. 1; see also Figs. 11 and 22). The following bony prominences can usually be palpated in the living subject (corresponding vertebral levels are given in brackets): •◊◊superior angle of the scapula (T2); •◊◊upper border of the manubrium sterni, the suprasternal notch (T2/3); •◊◊spine of the scapula (T3); •◊◊sternal angle (of Louis) — the transverse ridge at the manubrio-sternal junction (T4/5); •◊◊inferior angle of scapula (T8); •◊◊xiphisternal joint (T9); •◊◊lowest part of costal margin—10th rib (the subcostal line passes through L3). Note from Fig. 1 that the manubrium corresponds to the 3rd and 4th thoracic vertebrae and overlies the aortic arch, and that the sternum corre- sponds to the 5th to 8th vertebrae and neatly overlies the heart. Since the 1st and 12th ribs are difficult to feel, the ribs should be enu- merated from the 2nd costal cartilage, which articulates with the sternum at the angle of Louis. The spinous processes of all the thoracic vertebrae can be palpated in the midline posteriorly, but it should be remembered that the first spinous process that can be felt is that of C7 (the vertebra prominens). The position of the nipple varies considerably in the female, but in the male it usually lies in the 4th intercostal space about 4in (10cm) from the midline. -

Evaluation and Treatment of Selected Sacral Somatic Dysfunctions

Evaluation and Treatment of Selected Sacral Somatic Dysfunctions Using Direct and HVLA Techniques including Counterstrain and Muscle Energy AND Counterstrain Treatment of the Pelvis and Sacrum F. P. Wedel, D.O. Associate Adjunct Professor in Osteopathic Principles and Practice A.T. Still University School of Osteopathic Medicine in Arizona, and private practice in Family Medicine in Tucson, Arizona Learning Objectives HOURS 1 AND 2 Review the following diagnostic and treatment techniques related to sacral torsion Lumbosacral spring test Sacral palpation Seated flexion test HOURS 3 AND 4 Counterstrain treatments of various low back pathologies Sacral Techniques Covered : 1. Prone, direct, muscle energy, for sacral rotation on both same and opposite axes 2. HVLA treatment for sacral rotation on both same and opposite axes 3. Counterstain treatment of sacral tender points and of sacral torsion Counterstrain Multifidi and Rotatores : UP5L Gluteii – maximus: HFO-SI, HI, P 3L- P 4L ,medius, minimus Piriformis Background and Basis The 4 Osteopathic Tenets (Principles) 1. The body is a unit; the person is a unit of body, mind, and spirit. 2. Structure and function are reciprocally inter-related. 3. The body is capable of self- regulation, self-healing, and health maintenance. 4. Rational treatment is based upon an understanding of these basic principles. Somatic Dysfunction - Defined • “Impaired or altered function of related components of the somatic (body framework) system: • Skeletal, arthrodial, and myofascial structures, • And… • Related vascular, lymphatic, and neural elements” Treatment Options for Somatic Dysfunctions All somatic dysfunctions have a restrictive barrier which are considered “pathologic” This restriction inhibits movement in one direction which causes asymmetry within the joint: The goal of osteopathic treament is to eliminate the restrictive barrier thus restoring symmetry…. -

The Influence of the Rib Cage on the Static and Dynamic Stability

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The infuence of the rib cage on the static and dynamic stability responses of the scoliotic spine Shaowei Jia1,2, Liying Lin3, Hufei Yang2, Jie Fan2, Shunxin Zhang2 & Li Han3* The thoracic cage plays an important role in maintaining the stability of the thoracolumbar spine. In this study, the infuence of a rib cage on static and dynamic responses in normal and scoliotic spines was investigated. Four spinal fnite element (FE) models (T1–S), representing a normal spine with rib cage (N1), normal spine without rib cage (N2), a scoliotic spine with rib cage (S1) and a scoliotic spine without rib cage (S2), were established based on computed tomography (CT) images, and static, modal, and steady-state analyses were conducted. In S2, the Von Mises stress (VMS) was clearly decreased compared to S1 for four bending loadings. N2 and N1 showed a similar VMS to each other, and there was a signifcant increase in axial compression in N2 and S2 compared to N1 and S1, respectively. The U magnitude values of N2 and S2 were higher than in N1 and S1 for fve loadings, respectively. The resonant frequencies of N2 and S2 were lower than those in N1 and S1, respectively. In steady-state analysis, maximum amplitudes of vibration for N2 and S2 were signifcantly larger than N1 and S1, respectively. This study has revealed that the rib cage improves spinal stability in vibrating environments and contributes to stability in scoliotic spines under static and dynamic loadings. Scoliosis, a three-dimensional deformity, prevents healthy development. -

Structure of the Human Body

STRUCTURE OF THE HUMAN BODY Vertebral Levels 2011 - 2012 Landmarks and internal structures found at various vertebral levels. Vertebral Landmark Internal Significance Level • Bifurcation of common carotid artery. C3 Hyoid bone Superior border of thyroid C4 cartilage • Larynx ends; trachea begins • Pharynx ends; esophagus begins • Inferior thyroid A crosses posterior to carotid sheath. • Middle cervical sympathetic ganglion C6 Cricoid cartilage behind inf. thyroid a. • Inferior laryngeal nerve enters the larynx. • Vertebral a. enters the transverse. Foramen of C 6. • Thoracic duct reaches its greatest height C7 Vertebra prominens • Isthmus of thyroid gland Sternoclavicular joint (it is a • Highest point of apex of lung. T1 finger's breadth below the bismuth of the thyroid gland T1-2 Superior angle of the scapula T2 Jugular notch T3 Base of spine of scapula • Division between superior and inferior mediastinum • Ascending aorta ends T4 Sternal angle (of Louis) • Arch of aorta begins & ends. • Trachea ends; primary bronchi begin • Heart T5-9 Body of sternum T7 Inferior angle of scapula • Inferior vena cava passes through T8 diaphragm T9 Xiphisternal junction • Costal slips of diaphragm T9-L3 Costal margin • Esophagus through diaphragm T10 • Aorta through diaphragm • Thoracic duct through diaphragm T12 • Azygos V. through diaphragm • Pyloris of stomach immediately above and to the right of the midline. • Duodenojejunal flexure to the left of midline and immediately below it Tran pyloric plane: Found at the • Pancreas on a line with it L1 midpoint between the jugular • Origin of Superior Mesenteric artery notch and the pubic symphysis • Hilum of kidneys: left is above and right is below. • Celiac a. -

Biomechanics of the Thoracic Spine - Development of a Method to Measure the Influence of the Rib Cage on Thoracic Spine Movement

Universität Ulm Zentrum für Chirurgie Institut für Unfallchirurgische Forschung und Biomechanik Direktor: Prof. Dr. A. Ignatius Biomechanics of the Thoracic Spine - Development of a Method to Measure the Influence of the Rib Cage on Thoracic Spine Movement Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades der Medizin der Medizinischen Fakultät der Universität Ulm vorgelegt von: Konrad Appelt geboren in: Pforzheim 2012 Amtierender Dekan: Prof. Dr. Thomas Wirth 1. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. H.-J. Wilke 2. Berichterstatter: Prof. Dr. Tobias Böckers Tag der Promotion: 06.06.2013 Index List of abbreviations ......................................................................................IV 1 Introduction .............................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................. 1 1.2 State of Research .................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Objectives ............................................................................................................... 6 2 Material and methods .............................................................................. 7 2.1 Testing machines and devices ................................................................................. 7 2.1.1 Spine loading simulator ................................................................................... 7 2.1.2 Vicon – MX Motion Capture System -

Thoracic Cage EDU - Module 2 > Thorax & Spine > Thorax & Spine

Thoracic Cage EDU - Module 2 > Thorax & Spine > Thorax & Spine Thoracic cage • Protects the chest organs (the heart and lungs). Main Structures: The sternum (aka, breastbone) lies anteriorly. 12 thoracic vertebrae lie posteriorly. 12 ribs articulate with the thoracic vertebrae. Sternum • Manubrium (superiorly) • Body (long and flat, middle portion) • Xiphoid process - Easily injured during chest compression (for CPR). • Sternal angle - Where manubrium and body meet - Easily palpated to find rib 2 • Sternal indentations: - Jugular notch (aka, suprasternal notch) is on the superior border of the manubrium. - Clavicular notches are to the sides of the jugular notch; these are where the clavicles (aka, collarbones), articulate with the sternum. - Costal notches articulate with the costal cartilages of the ribs ("costal" refers to the ribs). Rib Types • True ribs - Ribs 1-7; articulate with the sternum directly via their costal cartilages. • False ribs - Ribs 8-12; do not articulate directly with the sternum. - Ribs 11 and 12 are "floating ribs," do not articulate at all with the sternum. 1 / 2 Rib Features • Head - Articulates with the vertebral body; typically comprises two articular surfaces separated by a bony crest. • Neck - Extends from the head, and terminates at the tubercle. • Tubercle - Comprises an articular facet, which is where the rib articulates with the transverse process of the vertebra. • Shaft - Longest portion of the rib, extends from tubercle to rib end. • Angle - Bend in rib, just lateral to tubercle. Rib/vertebra articulation • Head and tubercle of rib articulate with body and thoracic process of vertebrae. Intercostal spaces • The spaces between the ribs • House muscles and neurovascular structures. -

Lab Manual Axial Skeleton Atla

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES When studying the skeletal system, the bones are often sorted into two broad categories: the axial skeleton and the appendicular skeleton. This lab focuses on the axial skeleton, which consists of the bones that form the axis of the body. The axial skeleton includes bones in the skull, vertebrae, and thoracic cage, as well as the auditory ossicles and hyoid bone. In addition to learning about all the bones of the axial skeleton, it is also important to identify some significant bone markings. Bone markings can have many shapes, including holes, round or sharp projections, and shallow or deep valleys, among others. These markings on the bones serve many purposes, including forming attachments to other bones or muscles and allowing passage of a blood vessel or nerve. It is helpful to understand the meanings of some of the more common bone marking terms. Before we get started, look up the definitions of these common bone marking terms: Canal: Condyle: Facet: Fissure: Foramen: (see Module 10.18 Foramina of Skull) Fossa: Margin: Process: Throughout this exercise, you will notice bold terms. This is meant to focus your attention on these important words. Make sure you pay attention to any bold words and know how to explain their definitions and/or where they are located. Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the axial skeleton. As you explore these bones in Visible Body’s app, also locate the bones and bone markings on any available charts, models, or specimens. You may also find it helpful to palpate bones on yourself or make drawings of the bones with the bone markings labeled. -

Vertebral Column

Vertebral Column • Backbone consists of Cervical 26 vertebrae. • Five vertebral regions – Cervical vertebrae (7) Thoracic in the neck. – Thoracic vertebrae (12) in the thorax. – Lumbar vertebrae (5) in the lower back. Lumbar – Sacrum (5, fused). – Coccyx (4, fused). Sacrum Coccyx Scoliosis Lordosis Kyphosis Atlas (C1) Posterior tubercle Vertebral foramen Tubercle for transverse ligament Superior articular facet Transverse Transverse process foramen Facet for dens Anterior tubercle • Atlas- ring of bone, superior facets for occipital condyles. – Nodding movement signifies “yes”. Axis (C2) Spinous process Lamina Vertebral foramen Transverse foramen Transverse process Superior articular facet Odontoid process (dens) •Axis- dens or odontoid process is body of atlas. – Pivotal movement signifies “no”. Typical Cervical Vertebra (C3-C7) • Smaller bodies • Larger spinal canal • Transverse processes –Shorter – Transverse foramen for vertebral artery • Spinous processes of C2 to C6 often bifid • 1st and 2nd cervical vertebrae are unique – Atlas & axis Typical Cervical Vertebra Spinous process (bifid) Lamina Vertebral foramen Inferior articular process Superior articular process Transverse foramen Pedicle Transverse process Body Thoracic Vertebrae (T1-T12) • Larger and stronger bodies • Longer transverse & spinous processes • Demifacets on body for head of rib • Facets on transverse processes (T1-T10) for tubercle of rib Thoracic Vertebra- superior view Spinous process Transverse process Facet for tubercle of rib Lamina Superior articular process -

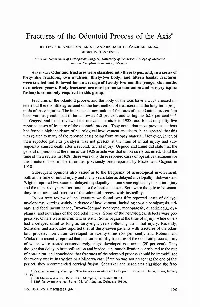

Fractures of the Odontoid Process of the Axis*

Fractures of the Odontoid Process of the Axis* BY LEWIS D. ANDERSON,M.D.?, AND RICHARD T. D'ALONZO,M.D.$, MEMPHIS, TENNESSEE From the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Tennessee College of Medicine and the Campbell Foundation, Memphis ABSTRACT:Odontoid fractures were classified into three types, and, in a series of forty-nine fractures, two avulsion, thirty-two body, and fifteen basilar fractures were treated and followed for an average of twenty-two months (range, six months to nineteen years). Body fractures are most prone to non-union and surgery (spine fusion) is commonly required in this group. Fractures of the odontoid process and the body of the axis have always aroused in- terest but there is little agreement on the best method of treatment and the long-term prog- nosis of these injuries. The incidence of non-union of fractures of the odontoid process has been variously estimated to be as low as 4.8 per cent and as high as 62.8 per cent 1,2,8- lo. Osgood and Lund reviewed the relevant literature in 1928, and found only fifty-five reported cases of fracture of the odontoid process. They noted that most previous authors had found a high incidence of neurological involvement and death, but suspected that this was related to many of the reported cases being from autopsy material. However, in ten of their reported patients paralysis was not present at the time of initial injury and sub- sequently caused death after a second, trivial injury. Osgood and Lund did state that the general impression at the time of the 1928 article was that union rarely occurred.