An Educational Approach to Create an Awareness and Understanding of the Marine Mammals That Inhabit the Waters of Puerto Rico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

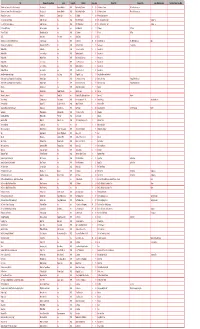

Louis Nicholas Song Collection

Title Composer/Arranger/Editor Lyricist Copyright Publisher Pages Box Original Title Translated Title Larger Work/Collection Translated Title of Large Work A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La) Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Menina e a Cancao (Fillette et la Chanson, La), c.2 Villa-Lobos, H. Andrade, Mario de 1925 Max Eschig & Cie Edrs 12 25 A Menina e a Cancao Fillette et la Chanson, La A Notre Dame sous-terre Chatillon, E. Chastel, Guy n/a E. Chatillon 7 30 A Notre Dame sous-terre A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora, c.2 Bellini, Vincenzo n/a 1946 Pro Art Publications 4 29 A Te, O Cara, Amore Talora Puritans, The A Trianon (At Trianon) Holmes, Augusta n/a n/a Harch Music Co. 4 19 A Trianon At Trianon A Vous (To Thee) D'Hardelot and Boyer n/a 1895 G. Schirmer 4 17 A Vous To Thee A.B.C. Parry, John Parry, John n/a Oliver Ditson 5 23 A.B.C. Abborrita rivale, L' (She, My Rival Detested) Verdi, Giuseppe n/a 1915 G. Schirmer 10 28 Abborrita rivale, L' She, My Rival Detested Aida Abendsegen (Evening-Prayer) Humperdinck and Wette n/a 1894 B. Schott's Sohne 2 28 Abendsegen Evening-Prayer Abide with Me Ashford, E.L. -

Crane Meadows National Wildlife Refuge Environmental Assessment

United States Department of the Interior NSH A¡ID WILDLIFE SERVICE Bishop Henry Whipple Fedcral Buitding I Fedcral Drive Fort Snelling, MN 55lll-4056 IN REILYNEFEN,T(} NWRS/CP Jlur:re29,2010 Dear Reviewer: We are pleased to provide you with this Draft Comprehensive Conservation Plan (CCP) and Environmental Assessment (EA) for Crane Meadows National Wildlife Refuge (NWR). Crane Meadows NWR was established in 1992 for'... the conservation of the wetlands of the Nation...' under the Emergency'Wetland Resources Act of 1986. The Service owns and manages approximately 1,800 acres of 13,540 acres proposed for acquisition in Morrison County, Minnesota. The unique wetland complex contains rare and declining habitat types, important archaeological resources, a diversity of local and migratory species, and an abundance of recreational opportunities. The CCP will guide management of the Refuge for the next 15 years and will help the Refuge meet its purpose and contribute to the mission of the National V/ildlife Refuge System. The CCP will provide both broad and specific guidance on various issues; describe the Refuge's vision, goals, and measurable objectives; and list strategies for reaching the objectives. We invite you to review and comment on the Draft CCP and EA. By sharing your thoughts, you can help ensure that the final CCP is both visionary and practical. V/e will host an open house where you will be able to ask questions and voice concerns and suggestions. This event will take place in the Refuge maintenance building from2 p.m. - 7 p.m. on Tuesday, July 20,2010. -

Notes Regarding CSRD in Puerto Rico

Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory Lessons and Possibilities Notes regarding CSRD in Puerto Rico a program of The Education Alliance at Brown University 222 Richmond Street, Suite 300, Providence, RI 02903-4226 Phone: 800.521.9550 E-mail: [email protected] Fax: 401.421.7650 Web: www.lab.brown.edu Lessons and Possibilities Notes regarding CSRD in Puerto Rico (based on site visits March 12-15 and September 10-14, 2000, and on reviews of literature and previous LAB CSRD involvement in Puerto Rico) Dr. Ted Hamann, Research and Development Specialist Dr. Odette Piñeiro, Puerto Rico Liaison Brett Lane, Program Planning Specialist/CSRD Dr. Patti Smith, Research and Development Specialist December, 2000 Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory a program of The Education Alliance at Brown University Northeast and Islands Regional Educational Laboratory At Brown University (LAB) The LAB, a program of The Education Alliance at Brown University, is one of ten educational laboratories funded by the U.S. Department of Education’s Office of Educational Research and Improvement. Our goals are to improve teaching and learning, advance school improvement, build capacity for reform, and develop strategic alliances with key members of the region’s education and policy-making community. The LAB develops educational products and services for school administrators, policymakers, teachers, and parents in New England, New York, Puerto Rico, and the Virgin Islands. Central to our efforts is a commitment to equity and excellence. Information about LAB programs and services is available by contacting: LAB at Brown University The Education Alliance 222 Richmond Street, Suite 300 Providence, RI 02903-4226 Phone: 800-521-9550 E-mail: [email protected] Web: www.lab.brown.edu Fax: 401-421-7650 Copyright © 2001 Brown University. -

Melendez-Ramirez.Pdf

NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARK NOMINATION NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CASA DRA. CONCHA MELÉNDEZ RAMÍREZ Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: Casa Dra. Concha Meléndez Ramírez Other Name/Site Number: Casa Biblioteca Dra. Concha Meléndez Ramírez 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 1400 Vilá Mayo Not for publication: City/Town: San Juan Vicinity: X State: Puerto Rico County: San Juan Code: 127 Zip Code: 00907 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: District: ___ Public-State: _X_ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: 1 Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 CASA DRA. CONCHA MELÉNDEZ RAMÍREZ Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

TANF & Head Start in Puerto Rico

With almost half of the population in poverty and vast proportions of the island immigrating to the United States for better prospects, Puerto Rican children and families are struggling. The following literature review provides a chronology of public assistance and poverty in Puerto Rico, summarizes the information available for two programs which offer support for families in poverty, and identifies directions for future research. POVERTY IN PUERTO RICO Under Spanish colonial rule, Puerto Rico developed an agricultural economy based on the production of coffee, sugar, cattle and tobacco. Rural, mountain-dwelling communities produced coffee on land unsuitable for other crops. These other crops, particularly sugar, were produced on relatively small tracts of land, or hacendados, owned by Spanish landowners. Laborers lived and worked on these haendados, and often afforded small plots of land to produce food for their families. The landowner-laborer relationship was especially important for the production of sugar, which requires heavy labor for a six month season, followed by an off-season. The hacendado system, although exploitative, provided for workers during the off-season (Baker, 2002). Under the United States’ direction, the economy in Puerto Rico shifted towards a sugar-crop economy controlled primarily by absentee American owners. This transformation had a devastating impact on the Puerto Rican economy and destroyed its ability to be agriculturally self-sustaining (Colón Reyes, 2011). First, as Puerto Ricans were no longer producing their own food, they relied on imports for the products they consumed. Reliance on imports meant that they paid higher prices than mainland US consumers for products while also receiving a lower wage than mainland US workers. -

Developing an Educational Module on the Impacts of Climate Change on Puerto Rico and Its Inhabitants

Developing an Educational Module on the Impacts of Climate Change on Puerto Rico and its Inhabitants An Interactive Qualifying Project (IQP) to be submitted to the Faculty of Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science SUBMITTED BY: PRINCESA CLOUTIER MICHAEL GAGLIANO EMMA RAYMOND SUBMITTED TO: PROJECT ADVISORS: PROF. LAUREN MATHEWS, WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE PROF. TINA-MARIE RANALLI, WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE PROJECT LIAISON: PEDRO RÍOS, UNITED STATES FOREST SERVICE Abstract Small islands like the island of Puerto Rico are susceptible to the negative effects of anthropogenic climate change. Because of this, it is important that climate change education is developed and implemented on the island so that the population, especially its youth, can adequately adapt to climate change. The goal of this project was to develop effective lessons that could be used to teach middle school students in Río Grande, Puerto Rico about the immediate and long-term effects of climate change. These lessons were designed to be relevant to the students by providing evidence and examples of climate change in the island of Puerto Rico. Through the use of interviews with experts on climate change, members of environmental education initiatives, and teachers, we were able to determine what material to incorporate into our lessons and how to best deliver it. To analyze the effectiveness of our lessons we tested our lesson on a ninth grade class and utilized a pre-test and a post-test as a method of evaluation. These tests asked questions based on the learning objectives covered in the lessons, and were then compared using statistical analysis. -

Weathering the Storm — Challenges For

Weathering the Storm – Challenges for PR’s Higher Education System Gloria Bonilla-Santiago, Ph.D., Heidie Calero, JD, Wanda Garcia, MSW, Matthew Closter MPA, MS, & Kiersten Westley-Henson, MA Natural disasters, such as hurricanes, economic disasters, bankruptcy, unmanageable government debt, and economic stagnation, present the opportunity for institutions of higher learning to assess their role as anchors of their communities (Crespo, Hlouskova & Obersteiner, 2008; Skidmore & Toya, 2002). Unfortunately, many of these institutions of higher learning are not prepared and aligned to deal with the devastation caused by widespread damage to flooded buildings, the financial impact caused by loss of tuition income, the significant disruptions on the lives of university students, faculty, and staff, In 2017, Hurricane Maria devastated outward migration, and the dysfunction of the Puerto Rico and shattered an already daily business of academia. struggling economy and the Island’s higher As one of the most diverse and education system (Meléndez & Hinojosa, accessible systems in the world, Higher 2017; Bonilla-Santiago, 2017). Hurricane Education performs an indispensable duty in Maria killed more than 90 people and caused the formation of future citizens, leaders, upwards of $100 Billion in damages in Puerto thinkers, and entrepreneurs; and plays a Rico. It also caused the loss of thousands of transformative role in community and crops as well as forced thousands to leave the economic development (Abel & Deitz, 2012). island, millions to lose their homes and many That was precisely the reason why then communities to be destroyed (Ferre, Sadurni, poor Government of Puerto Rico established Alvarez, & Robles, 2017). the University of Puerto Rico (state university) While the loss and devastation of a in 1903. -

Year 1 Volume 1-2/2014

MICHAELA PRAISLER Editor Cultural Intertexts Year 1 Volume 1-2/2014 Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Cluj-Napoca, 2014 Cultural Intertexts!! Journal of Literature, Cultural Studies and Linguistics published under the aegis of: ∇ Faculty of Letters – Department of English ∇ Research Centre Interface Research of the Original and Translated Text. Cognitive and Communicative Dimensions of the Message ∇ Doctoral School of Socio-Humanities ! Editing Team Editor-in-Chief: Michaela PRAISLER Editorial Board Oana-Celia GHEORGHIU Mihaela IFRIM Andreea IONESCU Editorial Secretary Lidia NECULA ! ISSN 2393-0624 ISSN-L 2393-0624 © 2014 Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Editura Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă Cluj-Napoca, Romania e-mail: [email protected] www.casacartii.ro SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Professor Elena CROITORU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Ioana MOHOR-IVAN, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Floriana POPESCU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Professor Mariana NEAGU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Ruxanda BONTILĂ, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Steluţa STAN, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Gabriela Iuliana COLIPCĂ-CIOBANU, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Gabriela DIMA, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Daniela ŢUCHEL, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Associate Professor Petru IAMANDI, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Senior Lecturer Isabela MERILĂ, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Senior Lecturer Cătălina NECULAI, Coventry University, UK Senior Lecturer Nicoleta CINPOEŞ, University of Worcester, UK Postdoc researcher Cristina CHIFANE, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi Postdoc researcher Alexandru PRAISLER, “Dunărea de Jos” University of Galaţi * The contributors are solely responsible for the scientific accuracy of their articles. -

Sounding Sentimental: American Popular Song from Nineteenth-Century Ballads to 1970S Soft Rock Emily Margot Gale Vancouver, BC B

Sounding Sentimental: American Popular Song From Nineteenth-Century Ballads to 1970s Soft Rock Emily Margot Gale Vancouver, BC Bachelor of Music, University of Ottawa, 2005 Master of Arts, Music Theory, University of Western Ontario, 2007 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Music University of Virginia May, 2014 © Copyright by Emily Margot Gale All Rights Reserved May 2014 For Ma with love iv ABSTRACT My dissertation examines the relationship between American popular song and “sentimentality.” While eighteenth-century discussions of sentimentality took it as a positive attribute in which feelings, “refined or elevated,” motivated the actions or dispositions of people, later texts often describe it pejoratively, as an “indulgence in superficial emotion.” This has led an entire corpus of nineteenth- and twentieth-century cultural production to be bracketed as “schmaltz” and derided as irrelevant by the academy. Their critics notwithstanding, sentimental songs have remained at the forefront of popular music production in the United States, where, as my project demonstrates, they have provided some of the country’s most visible and challenging constructions of race, class, gender, sexuality, nationality, and morality. My project recovers the centrality of sentimentalism to American popular music and culture and rethinks our understandings of the relationships between music and the public sphere. In doing so, I add the dimension of sound to the extant discourse of sentimentalism, explore a longer history of popular music in the United States than is typical of most narratives within popular music studies, and offer a critical examination of music that—though wildly successful in its own day—has been all but ignored by scholars. -

ESSA Puerto Rico State Plan Guidance 9.10.17 (PDF)

P a g e | 2 Introduction Section 8302 of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act of 1965 (ESEA), as amended by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA),1 requires the Secretary to establish procedures and criteria under which, after consultation with the Governor, a State educational agency (SEA) may submit a consolidated State plan designed to simplify the application requirements and reduce burden for SEAs. ESEA section 8302 also requires the Secretary to establish the descriptions, information, assurances, and other material required to be included in a consolidated State plan. Even though an SEA submits only the required information in its consolidated State plan, an SEA must still meet all ESEA requirements for each included program. In its consolidated State plan, each SEA may, but is not required to, include supplemental information such as its overall vision for improving outcomes for all students and its efforts to consult with and engage stakeholders when developing its consolidated State plan. Completing and Submitting a Consolidated State Plan Each SEA must address all of the requirements identified below for the programs that it chooses to include in its consolidated State plan. An SEA must use this template or a format that includes the required elements and that the State has developed working with the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSSO). Each SEA must submit to the U.S. Department of Education (Department) its consolidated State plan by one of the following two deadlines of the SEA’s choice: April 3, 2017; or September 18, 2017. Any plan that is received after April 3, but on or before September 18, 2017, will be considered to be submitted on September 18, 2017. -

The Daily Egyptian, April 19, 1972

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC April 1972 Daily Egyptian 1972 4-19-1972 The aiD ly Egyptian, April 19, 1972 Daily Egyptian Staff Follow this and additional works at: https://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/de_April1972 Volume 53, Issue 126 Recommended Citation , . "The aiD ly Egyptian, April 19, 1972." (Apr 1972). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daily Egyptian 1972 at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in April 1972 by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Council ok's street party •cover funds A $750 contingency fund to provide for initial insurance costs and to compen sate South Illinois Avenue service ~ , April 19, 11m-Vol. 53, No. 126 station owners for lost business during the coming street parties w~s authorized by the Carbondale City Council Tuesday night. • Steve Hoffmann, local liquor dealer and a spokesman for the South Illinois Avenue task force, told the council the contingency fund is needed to pay in surance costs, which he said would add up to $65 per night. Two service station owners whose businesses will be closed by the celebration will be paid about .., each for every night the street is closed. • Hoffmann said about 30 applications for activities and concessions have been received by the task force thus far, and "We expect that there will be at least 20 concessions. " A final schedule of acth·ilies for the firs t of six possible weekend celebrations will be presented to acliP.g City Manager Bill Schwegman Wed nesdav. -

The Politics of Education in Puerto Rico, 1898–1930

colonialism has shaped education in U.S.Puerto Rico since 1898, the year the United States went to war against Spain in Cuba and the Philippines.1 In the Age of Empire, the United States had strategic reasons for seeking overseas territories in the Caribbean and Pacific. Spain was a declining empire that had progressively lost its overseas colonies throughout the nineteenth centu- Colonial Lessons: ry. The Caribbean region, the site of a future isth- mian canal, was key to U.S. goals of economic and The Politics of military expansion. The 1898 war, notwithstanding objections from anti-imperialists, provided a timely opportunity for U.S. expansionists in government and industry. 2 Education in As part of its war against the Spanish in Cuba, the United States invaded the island of Puerto Rico on July 25, 1898. The war ended on December 10, 1898, Puerto Rico, when both nations signed the Treaty of Paris. The agreement transferred ownership of Spanish colo- nies in the Caribbean and the Pacific to the United 1898–1930 States. The United States thus emerged as an over- seas empire holding sovereignty over the islands of Solsiree del Moral Puerto Rico, Cuba, the Philippines, and Guam.3 Although the war ended in 1898, Puerto Ricans suffered under U.S. military occupation until 1900. The island’s political leaders were denied the right to participate in the 1898 Peace Treaty deliberations and in the 1900 U.S. Congressional debates and approval of the Foraker Act. With this act, the U.S. 40 The American Historian | May 2018 not exist.