OMAKASE by Weike Wang June 11, 2018

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nipples Covered in Wasabi? Florida Restaurant Has Naked Sushi on Menu

Home Autos Real Estate Jobs Classifieds Apps Place an Ad Buy Pictures Contests Reader Offers Login Register SITE BLOGS WEB Search powered by News Enter a search term... SS EE AA RR CC HH NYDN Home → Collections → AA bb c c NN e e ww s s Ads By Google Nipples covered in wasabi? Florida Recommend 109 restaurant has naked sushi on menu 0 0 StumbleUpon CHRISTINE ROBERTS Submit Tweet Sunday, August 05, 2012 Skin and sushi may seem like unlikely bedfellows, but not for one Miami Beach restaurant. Kung Fu Kitchen and Sushi at the Catalina Hotel & Beach Club is offering a complete sushi dinner on rather bare plates - nude models. Patrons willing to drop at least $500 can order as much as five to six feet of sushi on a scantily clad body, local television station WPLG reported. local10.com The restaurant owner says the models are washed like ‘surgeons’ before the dinner begins and banana leaves are strategically placed on the models’ private parts. Ads By Google FlatRate Moving® NYC "The Only Company I'll Ever Use". Official Site. 212 988 9292 www.FlatRate.com Bare the Musical RR EE LL AA TT EE DD AA RR TT II CC LL EE SS The Globally Acclaimed Rock Musical At New World Stages this Fall! www.baremusicalnyc.com Dish On Walters, Martha April 22, 2004 Tape shows Playboy model leaving Miami club hours "The chef basically makes an omakase, which is the Japanese word for chef's choice," the restaurant's before... owner, Nathan Lieberman, told WPLG. January 12, 2010 The restaurant has had three of the naked sushi feasts so far, according to ABC News. -

Omakase Moriawase from Bar Nigiri Or Sashimi

Omakase Salad & Tapas Chef’s choice from daily special menu Sashimi Salad 15 (with miso soup & daily salad) -assorted fish mixed spring salad Sushi 10 pcs 55 Mixed Green Salad 8.5 Wakame Seaweed Salad 5 Sashimi 12 pcs 55 Nigiri or Sashimi (2 piece) Sunomono - cucumber 6 Moriawase Sunomono with Tako or Ebi or Kani 9 V. Inari Sushi – Tofu skin 4 (with miso soup) Agedashi Tofu 7.5 Amaebi-Spot prawn 11 Sushi 6 pcs 22 Gyoza – pork cabbage 6.5 Blue Fin Tuna 12 -Maguro, Yellowtail, Salmon, Sea Bream, Soft Shell Crab 9 Ebi-Steamed prawn 5 Scallop & one more chef’s choice Chicken Karaage 7 Hamachi –Yellowtail 7 Sashimi 10 pcs 28 Mixed Tempura 15 Hotate – Hokkaido scallop 8 -Maguro, Yellowtail, Salmon, sea bream -2pc fish, 3pc prawn, 5 pc mixed veggie Ikura-Salt cured salmon roe 7 & one more chef’s choice Prawn Tempura – 5 pc 13 Ikura with quail egg 8 Yasai Tempura – 8 pc mixed veggie 10 Goemon Choice 8 pcs 25 Kampachi – Amber jack 9 Hamachi Kama 13 -3 pc Sushi : Maguro, Yellowtail, Salmon Kani-Snow crab 6 Grilled Whole Squid 12 & 5 pc Sashimi chef’s choice King Salmon 8 Saba Shioyaki 9.5 Kurodai – Sea bream 9 From Bar Maguro –Tuna 7 Ribeye Kushiyaki – 1 skewer 6 Kurobuta Belly – 1 Skewers 6 Uni Spoon – each person 15 Saba-Mackerel 6 Sake -Salmon 7 Chicken Yakitori – 1 skewer 5 - daily sea urchin, quail egg yolk, ikura Hamachi Truffle 17 Shiro maguro – Albacore tuna 7 Edamame 4 -yellowtail, kizami wasabi, truffle ponzu Tako- Octopus 6 Miso Soup 3.5 Tuna Tataki 17 Tamago- Egg omelette 6 Sushi Rice 3 Ankimo - Monk fish pate 7 Tobiko - Flying fish roe 6 Steam Rice 2.5 Kizami Chopped Wasabi 3 Tobiko with quail egg 6.5 Unagi- Grilled fresh water eel 7 Dinner Set (with miso soup) (with miso soup & rice) Chirashi Don 23 Udon Salmon Ikura Don 25 Chicken Karaage Udon 13 Saba Shioyaki 13 Hamachi Don 25 Mixed Tempura Udon 15 Chicken Teriyaki 14 Tekka Don 25 Prawn Tempura Udon 14 Salmon Teriyaki 15 Unagi Don 18 Veggie Tempura Udon 13 Ribeye Teri - M. -

Sushi in the United States, 1945--1970

Food and Foodways Explorations in the History and Culture of Human Nourishment ISSN: 0740-9710 (Print) 1542-3484 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gfof20 Sushi in the United States, 1945–1970 Jonas House To cite this article: Jonas House (2018): Sushi in the United States, 1945–1970, Food and Foodways, DOI: 10.1080/07409710.2017.1420353 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2017.1420353 © 2018 The Author(s). Taylor & Francis© 2018 Jonas House Published online: 24 Jan 2018. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 130 View related articles View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=gfof20 FOOD AND FOODWAYS https://doi.org/./.. Sushi in the United States, – Jonas House a,b aSociology of Consumption and Households, Wageningen University, Wageningen, Netherlands; bDepartment of Geography, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, UK ABSTRACT KEYWORDS Sushi first achieved widespread popularity in the United States in cuisine; new food; public the mid-1960s. Many accounts of sushi’s US establishment fore- acceptance; sushi; United ground the role of a small number of key actors, yet underplay States the role of a complex web of large-scale factors that provided the context in which sushi was able to flourish. This article critically reviews existing literature, arguing that sushi’s US popularity arose from contingent, long-term, and gradual processes. It exam- ines US newspaper accounts of sushi during 1945–1970, which suggest the discursive context for US acceptance of sushi was considerably more propitious than generally acknowledged. -

Autumn Omakase a TASTING MENU from TATSU NISHINO of NISHINO

autumn omakase A TASTING MENU FROM TATSU NISHINO OF NISHINO By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman Photographs by Peyman Oreizy First published in 2005 by tastingmenu.publishing Seattle, WA www.tastingmenu.com/publishing/ Copyright © 2005 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without prior consent of the publisher. Photographs © tastingmenu and Peyman Oreizy Autumn Omakase By Tatsu Nishino, Hillel Cooperman, photographs by Peyman Oreizy The typeface family used throughout is Gill Sans designed by Eric Gill in 1929-30. TABLE OF CONTENTS Tatsu Nishino and Nishino by Hillel Cooperman Introduction by Tatsu Nishino Autumn Omakase 17 Oyster, Salmon, Scallop Appetizer 29 Kampachi Usuzukuri 39 Seared Foie Gras, Maguro, and Shiitake Mushroom with Red Wine Soy Reduction 53 Matsutake Dobinmushi 63 Dungeness Crab, Friseé, Arugula, and Fuyu Persimmon Salad with Sesame Vinaigrette 73 Hirame Tempura Stuffed with Uni, Truffle, and Shiso 85 Hamachi with Balsamic Teriyaki 95 Toro Sushi, Three Ways 107 Plum Wine Fruit Gratin The Making of Autumn Omakase Who Did What Invitation TATSU NISHINO AND NISHINO In the United States, ethnic cuisines generally fit into convenient and simplistic categories. Mexican food is one monolithic cuisine, as is Chinese, Italian, and of course Japanese. Every Japanese restaurant serves miso soup, various tempura items, teriyaki, sushi, etc. The fact that Japanese cuisine is multi-faceted (as are most cuisines) and quite diverse doesn’t generally come through to the public—the American homogenization machine reduces an entire culture’s culinary contributions to a simple formula that can fit on one menu. -

Sushi Menu Sushi Bar Combo Classic Rolls

Spicy Sushi Rice Bowl / $23 Select chopped raw fish with assorted vegetables over steamed rice Sushi Bento Box / $25 Green Mussel (2pc), Seaweed Salad, Nigiri (3pc), Sashimi (6pc), Crunch Munch Roll 9326 Cedar Center Way All Side Sauces (2 oz.) / $0.75 Louisville, KY 40291 Phone: (502) 708-1500 www.sakeblue.com Classic Rolls Sushi Menu The MJ / $13 Spicy crawfish, fresh jalapeño, cream cheese, mozzarella cheese, spicy & eel sauce. Deep fried. Rainbow / $12 California roll with four kinds of fish fillets Snow Roll / $12 Spicy crab topped with salmon with wasabi sauce, crunch Sushi Bar Combo Fire Dragon / $13 Eel & cucumber topped with spicy tuna, sliced avocado, special hot sauce & soy sauce Heaven Roll / $11 Sashimi A / $20 Fried shrimp & cream cheese topped with mango, tuna with wasabi sauce & eel sauce 3 kinds of Sashimi, 3 pcs each Fried Shrimp / $11 Sashimi B / $28 Fried shrimp, crab, masago, avocado, cucumber, sweet soy sauce 4 kinds of Sashimi, 4 pcs each Crispy Dynamite Roll / $12 Sushi Combo A / $20 Spicy tuna, eel, asparagus, deep fried and topped with spicy mayo and 7pc sushi, Tuna Roll eel sauce Sushi Combo B / $29 California / $6 7pc sushi, 8pc Sashimi & Tuna Roll Crab, avocado, cucumber, masago (Spicy Crab $2) Sushi Combo C / $40 Dynamite Roll / $8 7pc sushi, 12pc Sashimi, California Roll, Cucumber Roll Five different kinds of fish tossed in spicy sauce Deluxe Combo / $60 Green Castle Roll / $12 12pc sushi, 15pc Sashimi, California Roll, Tuna Roll, Crunch Munch Tuna, salmon, green avocado. Wrapped with green soybean paper, white Roll sauce and green crunch Supreme Combo / $80 Cha-Cha / $13 20pc sushi, 20pc Sashimi, California Roll, Spicy Tuna Roll, Crunch Shrimp, crab, cream cheese, asparagus. -

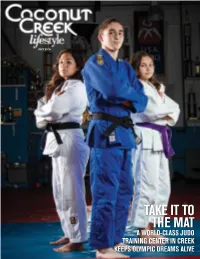

Take It to the Mat a World-Class Judo Training Center in Creek Keeps Olympic Dreams Alive Coconut Creek Lifestyle • July 2018 Lmgfl.Com • 1 Parks & Recreation

JULY 2018 TAKE IT TO THE MAT A WORLD-CLASS JUDO TRAINING CENTER IN CREEK KEEPS OLYMPIC DREAMS ALIVE COCONUT CREEK LIFESTYLE • JULY 2018 LMGFL.COM • 1 PARKS & RECREATION Coconut Creek Youth Soccer Drama Workshop National Parks & Recreation Month For more information, call (954) 545-6670 2 • LMGFL.COM COCONUT CREEK LIFESTYLE • JULY 2018 PARKS & RECREATION Coconut Creek Youth Soccer Drama Workshop National Parks & Recreation Month For more information, call (954) 545-6670 COCONUT CREEK LIFESTYLE • JULY 2018 LMGFL.COM • 3 contents July 2018 • Volume 18, Issue 7 • lmgfl.com FEATURES UNITED IN 24 EXCELLENCE Ki-Itsu-Sai National Training Center in Coconut Creek molds world-class judo athletes. THE 28 GOODS Product recommendations for a fun and productive summer. MEET YOUR 33 MAYO R Get to know new Coconut Creek mayor Joshua Rydell. DEPARTMENTS 5 LIFESTYLE GREETINGS 9 MAYOR’S MESSAGE 11 AROUND TOWN 16 ARTS & ENTERTAINMENT Guitar Center 18 BUSINESS Docking Bay 94 20 DINING Pad ai 30 DAY TRIPPER What’s new at Walt Disney World 34 CITY VOICE Coconut Creek’s IT Department 36 #MYCOCONUTCREEK On the cover: Giovanna, Jacob Stay connected to Coconut Creek and Maia, judo athletes who 38 GREEN EXCELLENCE train at Ki-Itsu-Sai National Training Center in Coconut Patriotic plants Creek. In their respective age 39 CREEK FAMILY PD divisions and weight categories, Tips to avoid scammers all three are ranked fi rst nation- 40 CALENDAR ally by USA Judo. 42 SNAPSHOTS This page: Ki-Itsu-Sai owner Photos from the city’s third Tree Planting Jhonny Prado and coach Ger- man Velazco Ceremony and Free Tree Giveaway 46 COMMUNITY SPOTLIGHT Location: Ki-Itsu-Sai National A nonprofi t promotes a life-saving law Training Center at 6855 Lyons Technology Circle, Suite 9, Coconut Creek Photos by: Eduardo Schneider Correction: The June issue gave the wrong phone number for Cookie Cutters. -

Tempura Cold Dishes Snacks and Salads Maki Rolls Nigiri / Sashimi

zuma omakase moriawase sushi platter premium classic premium menu is a selection of 10 dishes designed for the whole table to enjoy, price per person chef selection of nigiri, sashimi and maki rolls all served with fresh wasabi, price per person 30g oscietra caviar 30g beluga caviar served with miso buns, spring onions, fresh wasabi and yuzu cream snacks and salads cold dishes steamed edamame with sea salt(vg) blanched baby spinach, sesame dressing (vg) crispy fried calamari, green chilli, lime sliced yellowtail, green chilli, ponzu, pickled garlic zuma signature dishes watercress salad, avocado, wasabi, cucumber (v) tuna tataki, chilli daikon, citrus ponzu ` baby chicken, oven baked, barley miso, cedar wood spicy fried tofu, avocado, japanese herbs (vg) wagyu sirloin tataki, truffle ponzu, black truffle black cod, saikyo miso, hoba leaf zuma salad, tomato, eggplant, citrus dressing (vg) salmon and tuna tartare, miso bun, spring onions spicy beef tenderloin, sesame, chilli, garlic, sweet soy crab salad, sesame dressing, mizuna, tobiko add whole roasted lobster, garlic, shiso, ponzu-butter add 30g oscietra caviar 30g beluga caviar nigiri / sashimi tempura robata vegetables 2pc / 3pc maki rolls tiger prawn tempura, five pieces asparagus, wafu sauce, sesame (vg) hamachi/yellowtail zuma kappa, cucumber, avocado, pickled ginger (vg) shrimp tempura, shiso and citrus mayonnaise tenderstem broccoli, barley miso, shichimi (vg) sake/salmon zuma veggie roll, asparagus, avocado, carrots, shiso, ginger (vg) vegetable tempura, seven types of vegetables -

Nigiri Classiques Ryu Poke Sashimi Entrées Maki

NIGIRI にぎり寿司 2 MORCEAUX CLASSIQUES クラシック Albacore 6 Rêve Californien 14 Bar Rayé Sauvage 6 tartare de saumon, goberge, concombre, tempura, tobiko, feuille de soya, mayonnaise épicée, marmelade d’abricot Saumon 6 Nous sommes fier de nos produits, Pétoncle 6.50 Saumon Bio 14.50 Crevettes façon Ryu 6.50 Tartare de saumon, saumon à la torche, nori, le poisson est livré tous les matins et mayonnaise épicée Flétan Bio 7 le riz préparé plusieurs fois par Thon “Big Eye” 7 Arc-en-Ciel Ryu 15 jour selon la plus stricte tradition Thon, saumon, concombre, wakame, tempura, feuille de soya, Œufs de Saumon 7 papier de riz, mayonnaise épicée, mayonnaise basilic japonaise. Saumon Royal Bio 7. 5 0 Poké de Thon 15 Hamachi (Thon à queue jaune) 7. 5 0 Ce qui est bon pour vous l’est aussi pour Thon, goberge, concombre, sésame, nori, mayonnaise épicée, la planète. Nous servons des produits de la Wagyu 13 sauce poke mer 100% issu de la pêche durable et dont Thon Cajun l’origine est certifiée 16 SPÉCIAUX スペシャル SELON DISPONIBILITÉ Tartare de Thon, Thon à la torche tōgarashi, oignon vert, nori, mayonnaise épicé Uni 14 Flétan 16 Chūtoro (2x) 15 Flétan, bar rayé sauvage, concombre, nori, chips d’ail, Uni, Chūtoro 12 tempura, aïoli, aji Amarillo Uni, Toro, Œufs de Saumon 14 Pétoncle Wasabi 18 Uni, Wagyu 15 Pétoncle, thon, concombre, oba, nori, mayonnaise wasabi, ENTRÉES 先付け purée de pruneaux, ponzu Edamame (sans OGM) 4 Soupe Miso 4 巻き寿司 TEMAKI MAKI (8x) ポク Salade Wakame 4.50 MAKI RYU POKE Concombre 5 6 Thon 18 お刺身 Saumon épicé + 0.50 6 8 Sésame shoyu, wakame, concombre, tobiko, oignon vert, nori, chips d’ail, wasabi SASHIMI Pétoncle épicé + 0.50 6.50 8 Saumon 17 Tataki de Saumon Bio 8.50 Thon épicé + 0.50 7. -

New Convoy Sushi Bar Hidden Fish Goes All-In on Omakase

New Convoy sushi bar Hidden Fish goes all-in on omakase The interior of the newly opened Hidden Fish Sushi Bar, which serves an all-omakase menu, on Convoy Street in Kearny Mesa. (Courtesy photo) Most San Diego sushi restaurants offer an “omakase” option, a phrase meaning the diner entrusts the chef to choose his or her best dishes to send to the table. Some spots offer the service daily; some by reservation only; and some have chefs so respected that most customers prefer the omakase option. These meals can cost as much as $300 and stretch over three hours. Now comes Hidden Fish, San Diego’s first omakase-only sushi bar, which held its soft opening Tuesday on Convoy Street in Kearny Mesa. Owner John Hong, who works under the name “Chef Kappa,” said his sleek and industrial/modern 13-seat sushi bar is an idea many years in the making. John "Chef Kappa" Hong, 31, who has worked at Bang Bang and Sushi Ota, has opened the omakase- only Hidden Fish sushi restaurant this week on Convoy Street. (Courtesy photo) The 31-year-old Kearny Mesa resident has been in the sushi trade for 14 years, learning the craft in his native L.A. from sushi master Yukio Sakai. Most recently he worked at Sushi Ota in Pacific Beach, and before that spent four years leading the kitchen at Bang Bang in the Gaslamp Quarter. “This is my dream,” Hong of this restaurant, which offers only bar seating, no tables. “I love the idea of interacting one on one with customers. -

SANRAKU METREON Special

SANRAKU METREON Special Uni Toro Don $45 -Chu Toro, sea urchin, marinated blue fin tuna, chopped fatty tuna, shiso leaf, and sesame seeds over sushi rice- Hokkaido Chirashi Gozen $38 -Sea urchin, fresh crab, sweet shrimp, scallop and salmon roe over sushi rice with more side appetizers- Saikyo Yaki Bento Box $24 -Broiled miso marinated black cod, assorted seasoned vegetables with steamed rice- Poke Donburi $18 -Poke bowl with tuna, salmon, albacore, tobiko, avocado, edamame, seaweed salad, garlic ponzu & spicy miso sauce over sushi rice - Ocean Cobb Salad $15 -Grilled salmon, crab stick, soy marinated boiled egg with chopped organic greens, ginger vinegar dressing- ‘Homemade’ Dashimaki Tamago $9 -Japanese style layered egg omelet- Sushi / Sashimi Omakase Nigiri -Chef’s best selection of 10pcs Nigiri sushi from today’s special- $55 Sushi Platter -Tuna, Yellowtail, Salmon, Shrimp, White Tuna, Eel & 6pcs California Roll- $25 Sashimi Platter -Chef’s choice of 12 pcs sliced raw fish with side steamed rice- $30 Sushi & Sashimi Platter -Chef’s choice of 6 pcs Nigiri, 7pcs Sashimi, & 6pcs California Roll- $38 Sashimi Salad -Assorted sashimi topped on mixed greens, house dressing- $18 Chirashi Sushi -Assorted sliced of raw fish, garnish, over sushi rice- $30 Donburi & Noodle Una Ten Donburi -BBQ eel, shrimp tempura, soft boiled egg, over rice- $25 Beef Donburi -Stir fried thinly sliced beef rib-eye and vegs with teriyaki sauce, over rice- $19 Ten Zaru Soba -Cold- -Japanese buckwheat noodle with dipping sauce, aside of shrimp & vegetable tempura-$15 -

Summer Menu-210611

Summer Menu We hope you enjoy your dining experience at Tahk Omakase where we practice Edo-mae, a traditional technique to cut, filet, season and preserve. Our menu is created with only top-quality, sustainable ingredients from the Toyosu Fish Market in Tokyo, Japan. TahkSushi.com EDO-MAE SUSHI & SALADS SEAWEED SALAD marinated sesame seaweed garnished with tosaka and ponzu sauce $7 SALMON SKIN SALAD mixed greens, yama gobo, cucumber and daikon sprouts, topped with shredded nori, bonito flakes, roasted sesame seeds and ponzu sauce $15 SUNOMONO CUCUMBER WITH KANI GF marinated sliced English cucumber with sweet rice vinegar, topped with Canadian snow crab legs (3pcs) and roasted sesame seeds $14 SHIRO MISO WITH TOFU GF white bone stock finished with white miso and medium firm tofu, ASK YOUR garnished with green onion $9 SERVER IZAKAYA HOT FOOD ABOUT OUR FRESH DAILY EDAMAME soybeans blanched and served with Japanese sea salt $7 GF NIGIRI* & SHISHITO PEPPERS flash fried , tossed in sweet garlic soy, topped with bonito flakes and roasted sesame SASHIMI* seeds $10 SELECTIONS GYOZA (5) pork & vegetable pan seared dumplings, steamed in sake, and served with ponzu sauce $10 BEEF TATAKI* U.S. Choice Angus beef tenderloin seared and thinly sliced on a bed of arugula with FRESH cherry tomatoes and served with tataki sauce $17 WASABI SHRIMP TEMPURA (4) lightly deep fried jumbo tiger shrimp, served with hot tempura broth dipping sauce $15 $6 CRAB TEMPURA (10) Canadian snow crab legs + claws lightly deep fried and served with hot tempura broth dipping sauce -

Renkon Omakase Sashimi

RENKO N SIGN ATUR E SKEWERS 1 / 3 SKEWERS SIGNATURE 1 3 1 3 TERIYAKI CHICKEN THIGH 55 / 140 KING OYSTER MUSHROOM 5 5 / 120 M AYO, S H ICH IMI FURIKA K E CHICKEN ACHILLES 60 / 160 BABY OCTOPUS 45 / 120 SHICHIMI KEWPIE MAYO, O KONOMI S A U C E PORK MEATBALL 65 / 160 HOKKAIDO SCALLOP & BACON 140 / 310 E GG YO L K , TA R E S A UCE PONZU, SHICH IMI LIMITED CHICKEN OYSTER 95 / 250 A4 WAGYU 395 / 8 9 0 LEMO N K AG OSHIMA WAG Y U, S A LT, W ILD PEPPER 1 3 1 3 CHICKEN THIGH 55 / 14 0 BABY SQUID 7 0 / 160 LEMO N, S H ICH IMI SPIC Y TERIYA KI, RENKO N SEA SONING CHICKEN WINGS 60 / 160 SALMON 130 / 300 LEMO N, S H ICH IMI IKURA , TATA KI SA UCE CHICKEN SKIN 30 / 7 0 TIGER PRAWN 95 / 2 5 0 LIME, SAK E, SALT LEMON, SHICH IMI CHICKEN GIZZARD 30 / 7 0 OKRA 35 / 8 0 G A R LIC C H IPS, TA R E SA UCE T OMAT O, G A R LIC MISO CHICKEN HEART 30 / 7 0 EGGPLANT 65 / 1 5 0 G ING E R & SCA LLION O I L H O USE MISO PORK BELLY 60 / 160 MISO, K A R A S H I DEFINITIONS RENKON : "LOTUS ROOT" IN JAPANESE, REFERENCE TO THE NATIONAL FLOWER OF VIETNAM PORK RIB 60 / 160 AS WELL AS OUR TEAMS DEEP ROOTS IN THE COUNTRY NEG I, TA RE SA U C E SHICHIMI: COMMON JAPANESE SPICE MIXTURE CONTAINING SEVEN INGREDIENTS TARE SAUCE: SAUCE OF SOY, SAKE AND MIRIN USED IN YAKITORI GRILLING FURIKAKE: JAPANESE RICE SEASONING CONTAINING SESAME, DRIED FISH, SALT MIXED SKEWERS 3 SKEWERS 1 EACH KEWPIE: JAPANESE MAYO OKONOMI: UMAMI PACKED SAUCE WITH KETCHUP, SOY, WORCESTERSHIRE KAGOSHIMA: PREFECTURE ON THE ISLAND OF KYUSYU KNOWN FOR ITS MARBLED BEEF VEGETABLE SKEWERS 1 1 0 KARASHI: JAPANESE MUSTARD,