Some Island Names in the Former 'Kingdom of the Isles'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inner and Outer Hebrides Hiking Adventure

Dun Ara, Isle of Mull Inner and Outer Hebrides hiking adventure Visiting some great ancient and medieval sites This trip takes us along Scotland’s west coast from the Isle of 9 Mull in the south, along the western edge of highland Scotland Lewis to the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides (Western Isles), 8 STORNOWAY sometimes along the mainland coast, but more often across beautiful and fascinating islands. This is the perfect opportunity Harris to explore all that the western Highlands and Islands of Scotland have to offer: prehistoric stone circles, burial cairns, and settlements, Gaelic culture; and remarkable wildlife—all 7 amidst dramatic land- and seascapes. Most of the tour will be off the well-beaten tourist trail through 6 some of Scotland’s most magnificent scenery. We will hike on seven islands. Sculpted by the sea, these islands have long and Skye varied coastlines, with high cliffs, sea lochs or fjords, sandy and rocky bays, caves and arches - always something new to draw 5 INVERNESSyou on around the next corner. Highlights • Tobermory, Mull; • Boat trip to and walks on the Isles of Staffa, with its basalt columns, MALLAIG and Iona with a visit to Iona Abbey; 4 • The sandy beaches on the Isle of Harris; • Boat trip and hike to Loch Coruisk on Skye; • Walk to the tidal island of Oronsay; 2 • Visit to the Standing Stones of Calanish on Lewis. 10 Staffa • Butt of Lewis hike. 3 Mull 2 1 Iona OBAN Kintyre Islay GLASGOW EDINBURGH 1. Glasgow - Isle of Mull 6. Talisker distillery, Oronsay, Iona Abbey 2. -

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property

Lionel Mission Hall, Lionel, Isle of Lewis, HS2 0XD Property Detached church building located in the peaceful village of Lionel, to the north of the Isle of Lewis. With open views surrounding, the property benefits from a wonderful spot and presents a very attractive purchase opportunity and is only a short drive from the main town of Stornoway. Entrance Vestibule: 2.59m x 2.25m Main Hall: 10.85m x 6.46m Gross Internal Floor Area: 76.2 m2 Services The property is serviced by electricity only. Mains water and sewer are conveniently located nearby. Grounds The property is situated on a small plot, with grounds surrounding the church bounded by wire fencing. Planning The Church Hall is not listed, and could be used, without the necessity of obtaining change of use consent, as a Creche, day nursery, day centre, educational establishment, museum or public library. It also has potential for a variety of other uses, such as retail, commercial or community uses, subject to obtaining the appropriate consents. Conversion to residential accommodation is also possible, again subject to the usual consents. Local Area Lionel is a village on the North of the Isle of Lewis and is less than a ten-minute drive from the Butt of Lewis. The village benefits from excellent access routes around the island and is only 26 miles from Stornoway. The neighbouring villages provide a wide range of amenities including shop, filling station, school, post office, bar restaurant, laundrette and charity shop. Stornoway is the main town of the Western Isles and the capital of Lewis. -

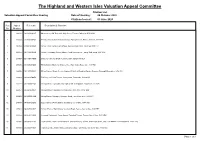

Appeal Citation List External

The Highland and Western Isles Valuation Appeal Committee Citation List Valuation Appeal Committee Hearing Date of Hearing : 06 October 2020 Citations Issued : 05 June 2020 Seq Appeal Reference Description & Situation No Number 1 269288 01/01/388013/7 Museum etc, Old Town Hall, High Street, Thurso, Caithness, KW14 8AJ 2 299360 01/05/010080/1 Primary School, Noss Primary School, Ackergill Street, Wick, Caithness, KW1 4DT 3 299359 01/05/585000/8 School, Wick Community Campus, Newton Road, Wick, Caithness, KW1 5LT 4 299358 02/11/027950/9 School, Secondary School, Manse Road, Kinlochbervie, Lairg, Sutherland, IV27 4RG 5 299357 02/13/081300/0 Distillery, Clynelish Distillery, Brora, Sutherland, KW9 6LR 6 259285 03/12/020600/4 Filling Station, Black Isle Motors, Tore, Muir of Ord, Ross-shire, IV6 7RZ 7 266056 03/21/009580/2 Filling Station, Skiach Service Station, 4D Airfield Road Ind Estate, Evanton, Dingwall, Ross-shire, IV16 9XJ 8 299363 03/23/335005/0 Distillery, Golf View Terrace, Invergordon, Ross-shire, IV18 0HW 9 259242 03/23/380240/5 Filling Station, Four Oaks, 130 High Street, Invergordon, Ross-shire, IV18 0AE 10 266057 03/32/465005/4 Filling Station, 1 Knockbreck Road, Tain, Ross-shire, IV19 1BW 11 266058 03/32/555164/0 Filling Station, Morangie, Morangie Road, Tain, Ross-shire, IV19 1PY 12 265484 04/05/032820/2 Supermarket & Filling Station, Broadford, Isle of Skye, IV49 9AB 13 299361 04/06/036250/2 School, Portree High School, Viewfield Road, Portree, Isle of Skye, IV51 9ET 14 299268 04/06/041450/8 Licensed Restaurant, Caroy House, -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Where to Go: Puffin Colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 Puffin Pairs Were Recorded in Ireland at the Time of the Last Census

Where to go: puffin colonies in Ireland Over 15,000 puffin pairs were recorded in Ireland at the time of the last census. We are interested in receiving your photos from ANY colony and the grid references for known puffin locations are given in the table. The largest and most accessible colonies here are Great Skellig and Great Saltee. Start Number Site Access for Pufferazzi Further information Grid of pairs Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Skellig V247607 4,000 worldheritageireland.ie/skellig-michael check local access arrangements Puffin Island - Kerry V336674 3,000 Access more difficult Boat trips available but landing not possible 1,522 Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Great Saltee X950970 salteeislands.info check local access arrangements Mayo Islands l550938 1,500 Access more difficult Illanmaster F930427 1,355 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Cliffs of Moher, SPA R034913 1,075 check local access arrangements Stags of Broadhaven F840480 1,000 Access more difficult Tory Island and Bloody B878455 894 Access more difficult Foreland Kid Island F785435 370 Access more difficult Little Saltee - Wexford X968994 300 Access more difficult Inishvickillane V208917 170 Access more difficult Access possible for Puffarazzi, but Horn Head C005413 150 check local access arrangements Lambay Island O316514 87 Access more difficult Pig Island F880437 85 Access more difficult Inishturk Island L594748 80 Access more difficult Clare Island L652856 25 Access more difficult Beldog Harbour to Kid F785435 21 Access more difficult Island Mayo: North West F483156 7 Access more difficult Islands Ireland’s Eye O285414 4 Access more difficult Howth Head O299389 2 Access more difficult Wicklow Head T344925 1 Access more difficult Where to go: puffin colonies in Inner Hebrides Over 2,000 puffin pairs were recorded in the Inner Hebrides at the time of the last census. -

The Genetic Landscape of Scotland and the Isles

The genetic landscape of Scotland and the Isles Edmund Gilberta,b, Seamus O’Reillyc, Michael Merriganc, Darren McGettiganc, Veronique Vitartd, Peter K. Joshie, David W. Clarke, Harry Campbelle, Caroline Haywardd, Susan M. Ringf,g, Jean Goldingh, Stephanie Goodfellowi, Pau Navarrod, Shona M. Kerrd, Carmen Amadord, Archie Campbellj, Chris S. Haleyd,k, David J. Porteousj, Gianpiero L. Cavalleria,b,1, and James F. Wilsond,e,1,2 aSchool of Pharmacy and Molecular and Cellular Therapeutics, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; bFutureNeuro Research Centre, Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland, Dublin D02 YN77, Ireland; cGenealogical Society of Ireland, Dún Laoghaire, Co. Dublin A96 AD76, Ireland; dMedical Research Council Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh EH4 2XU, Scotland; eCentre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh EH8 9AG, Scotland; fBristol Bioresource Laboratories, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; gMedical Research Council Integrative Epidemiology Unit at the University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 2BN, United Kingdom; hCentre for Academic Child Health, Population Health Sciences, Bristol Medical School, University of Bristol, Bristol BS8 1NU, United Kingdom; iPrivate address, Isle of Man IM7 2EA, Isle of Man; jCentre for Genomic and Experimental Medicine, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Towards a Sonic Methodology Cathy

Island Studies Journal , Vol. 11, No. 2, 2016, pp. 343-358 Mapping the Outer Hebrides in sound: towards a sonic methodology Cathy Lane University of the Arts London, United Kingdom [email protected] ABSTRACT: Scottish Gaelic is still widely spoken in the Outer Hebrides, remote islands off the West Coast of Scotland, and the islands have a rich and distinctive cultural identity, as well as a complex history of settlement and migrations. Almost every geographical feature on the islands has a name which reflects this history and culture. This paper discusses research which uses sound and listening to investigate the relationship of the islands’ inhabitants, young and old, to placenames and the resonant histories which are enshrined in them and reveals them, in their spoken form, as dynamic mnemonics for complex webs of memories. I speculate on why this ‘place-speech’ might have arisen from specific aspects of Hebridean history and culture and how sound can offer a new way of understanding the relationship between people and island toponymies. Keywords: Gaelic, island, landscape, memory, Outer Hebrides, place-speech, sound © 2016 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada Introduction I am a composer, sound artist and academic. In my creative practice I compose concert works and gallery installations. My current practice focuses around sound-based investigations of a place or theme and uses a mixture of field recording, interview, spoken text and existing oral history archive recordings as material. I am interested in the semantic and the abstract sonic qualities of all this material and I use it to construct “docu-music” (Lane, 2006). -

Site Selection Document: Summary of the Scientific Case for Site Selection

West Coast of the Outer Hebrides Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) No. UK9020319 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Scotland Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed in preparation for possible formal Scotland consultation. 30/06/15 Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Updated with minor amendments to address Marine comments from Marine Scotland Science in Scotland preparation for the SPA stakeholder workshop. 23/02/16 Emma Philip Version 4 Revised format, using West Coast of Outer MPA Hebrides as a template, to address comments Project received at the SPA stakeholder workshop. Steering Emma Philip Group 07/04/16 Version 5 Text updated to reflect proposed level of detail for Marine final versions. Scotland Emma Philip 18/04/16 Version 6 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Glen Tyler & Emma Philip 19/06/16 Version 7 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 20/6/16 Version 8 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 9 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1 2. Site summary ..................................................................................................... 2 3. Bird survey information .................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines ................................. 7 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................ 13 6. Information on qualifying species ................................................................. -

Sport & Activity Directory Uist 2019

Uist’s Sport & Activity Directory *DRAFT COPY* 2 Foreword 2 Welcome to the Sport & Activity Directory for Uist! This booklet was produced by NHS Western Isles and supported by the sports division of Comhairle nan Eilean Siar and wider organisations. The purpose of creating this directory is to enable you to find sports and activities and other useful organisations in Uist which promote sport and leisure. We intend to continue to update the directory, so please let us know of any additions, mistakes or changes. To our knowledge the details listed are correct at the time of printing. The most up to date version will be found online at: www.promotionswi.scot.nhs.uk To be added to the directory or to update any details contact: : Alison MacDonald Senior Health Promotion Officer NHS Western Isles 42 Winfield Way, Balivanich Isle of Benbecula HS7 5LH Tel No: 01870 602588 Email: [email protected] . 2 2 CONTENTS 3 Tai Chi 7 Page Uist Riding Club 7 Foreword 2 Uist Volleyball Club 8 Western Isles Sports Organisations Walk Football (40+) 8 Uist & Barra Sports Council 4 W.I. Company 1 Highland Cadets 8 Uist & Barra Sports Hub 4 Yoga for Life 8 Zumba Uibhist 8 Western Isles Island Games Association 4 Other Contacts Uist & Barra Sports Council Members Ceolas Button and Bow Club 8 Askernish Golf Course 5 Cluich @ CKC 8 Benbecula Clay Pigeon Club 5 Coisir Ghaidhlig Uibhist 8 Benbecula Golf Club 5 Sgioba Drama Uibhist 8 Benbecula Runs 5 Traditional Spinning 8 Berneray Coastal Rowing 5 Taigh Chearsabhagh Art Classes 8 Berneray Community Association -

S. S. N. S. Norse and Gaelic Coastal Terminology in the Western Isles It

3 S. S. N. S. Norse and Gaelic Coastal Terminology in the Western Isles It is probably true to say that the most enduring aspect of Norse place-names in the Hebrides, if we expect settlement names, has been the toponymy of the sea coast. This is perhaps not surprising, when we consider the importance of the sea and the seashore in the economy of the islands throughout history. The interplay of agriculture and fishing has contributed in no small measure to the great variety of toponymic terms which are to be found in the islands. Moreover, the broken nature of the island coasts, and the variety of scenery which they afford, have ensured the survival of a great number of coastal terms, both in Gaelic and Norse. The purpose of this paper, then, is to examine these terms with a Norse content in the hope of assessing the importance of the two languages in the various islands concerned. The distribution of Norse names in the Hebrides has already attracted scholars like Oftedal and Nicolaisen, who have concen trated on establis'hed settlement names, such as the village names of Lewis (OftedaI1954) and the major Norse settlement elements (Nicolaisen, S.H.R. 1969). These studies, however, have limited themselves to settlement names, although both would recognise that the less important names also merit study in an intensive way. The field-work done by the Scottish Place Name Survey, and localised studies like those done by MacAulay (TGSI, 1972) have gone some way to rectifying this omission, but the amount of material available is enormous, and it may be some years yet before it is assembled in a form which can be of use to scholar ship. -

The Isle of Lewis & Harris (Chaps. VII & VIII)

THE ISLE OF LEWIS AND HARRIS CHAPTER I A STUDY IN ENVIRONMENT AND LANDSCAPE BRITISH COMMUNITY (A) THE GEOGRAPHIC SETTING: THE BRITISH ISLES, SCOTLAND AND THE by HIGHLANDS AND ISLES ARTHUR GEDDES i. A 'Heart' of the 'North and West' of Britain The Isle of Lewis and Harris (1955) by Arthur Geddes, the son N the ' Outer' Hebrides, commonly regarded as the of the great planner and pioneering human ecologist Patrick Geddes, is long out of print from EUP and hard to procure. most ' outlying ' inhabited lands of the British Isles, Chapters VII and VIII on the spiritual and religious life of the I are revealed not only the most ancient of British rocks, community remain of very great importance, and this PDF of the Archaean, but probably the oldest form of communal them has been produced for my students' use and not for any life in Britain. This life, in present and past, will interest commercial purpose. Also, below is Geddes' remarkable map of the Hebrides from p. 3, and at the back the contents pages. Alastair Mclntosh, Honorary Fellow, University of Edinburgh. EDINBURGH AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS *955 FIG. I.—Global view of the ' Outer' Hebrides, seen as the heart of the ' North and West' of Britain. 3 CH. VII SPIRITUAL LIFE OF COMMUNITY xviii. 19-20). The worldly wise might think that the spiritual fare of these poor folk must have been lean indeed ; while others, having heard much of the Highlanders' ' pagan ' superstitions, may think even worse ! The evi CHAPTER VII dence from which to judge is found in survivals from a rich lore, and for most readers seen but ' darkly' through THE SPIRITUAL LIFE OF THE prose translations from the poetry of a tongue now known COMMUNITY to few.