PDF Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treble Culture

OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN P A R T I FREQUENCY-RANGE AESTHETICS ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4411 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:53:21:53 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN ooxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.inddxfordhb-9780199913657-part-1.indd 4422 77/9/2007/9/2007 88:21:54:21:54 AAMM OUP UNCORRECTED PROOF – FIRSTPROOFS, Mon Jul 09 2007, NEWGEN CHAPTER 2 TREBLE CULTURE WAYNE MARSHALL We’ve all had those times where we’re stuck on the bus with some insuf- ferable little shit blaring out the freshest off erings from Da Urban Classix Colleckshun Volyoom: 53 (or whatevs) on a tinny set of Walkman phone speakers. I don’t really fi nd that kind of music off ensive, I’m just indiff er- ent towards it but every time I hear something like this it just winds me up how shit it sounds. Does audio quality matter to these kids? I mean, isn’t it nice to actually be able to hear all the diff erent parts of the track going on at a decent level of sound quality rather than it sounding like it was recorded in a pair of socks? —A commenter called “cassette” 1 . do the missing data matter when you’re listening on the train? —Jonathan Sterne (2006a:339) At the end of the fi rst decade of the twenty-fi rst century, with the possibilities for high-fi delity recording at a democratized high and “bass culture” more globally present than ever, we face the irony that people are listening to music, with increasing frequency if not ubiquity, primarily through small plastic -

It'sallfight Onthenight

60 ............... Friday, December 18, 2015 1SM 1SM Friday, December 18, 2015 ............... 61 WE CHECK OUT THE ACTION AT CAPCOM CUP NEW TRACKLIST MUSIC By Jim Gellately It’s all fight 1. Runaway 2. Conqueror LOST IN VANCOUVER Who: Jake Morgan (vocals 3. Running With The /guitar), Connor Mckay (gui- Wolves tar), Brandon Sherrett (bass/ vocals), Tom Lawrence on the night 4. Lucky (drums). Where: Kirkcaldy/Edinburgh. 5. Winter Bird For fans of: Stereophonics, 6. I Went Too Far Catfish And The Bottlemen, Oasis. 7. Through The Eyes Jim says: Lost In Vancouver Of A Child only recently released their first couple of singles, but 8. Warrior their story goes back around 9. Murder Song (5, five years. They first got together at GLOBAL rivals in the By LEE PRICE By JACQUI SWIFT 4, 3, 2, 1) their local YMCA in Kirkcaldy, which runs a thriving youth world’s top fighting and T-shirts emblazoned A COFFEE shop in 10. Home music programme. game went toe-to- with the logos of their vari- Gatwick Airport’s 11. Under The Water Jake told me: “From the toe as they battled ous sponsors. age of 13, Brandon, Connor And the response from departures lounge 12. Black Water Lilies and myself had been getting to become Street the audience, who paid £25 is not the most guitar and song-writing les- Fighter champion. a ticket, was deafening. sons from a guy called Mark Before a sell-out crowd, At one point, the audito- glamorous setting Burdett. He got us playing in and hundreds of thousands rium chanted “USA! USA!” bands around the town.” following the action online, as a home favourite stepped to meet a fast-rising Jake and original drummer 32 gamers competed for a up, only to be silenced by James Ballingall were previ- share of £165,000 last week. -

Risktaking Behavior in Juvenile Myoclonic Epilepsy

FULL-LENGTH ORIGINAL RESEARCH Risk-taking behavior in juvenile myoclonic epilepsy *†Britta Wandschneider, *†Maria Centeno, *†‡Christian Vollmar, *†Jason Stretton, §Jonathan O’Muircheartaigh, *†Pamela J. Thompson, ¶Veena Kumari, *†Mark Symms, §Gareth J. Barker, *†John S. Duncan, #Mark P. Richardson, and *†Matthias J. Koepp Epilepsia, 0(0):1–8, 2013 doi: 10.1111/epi.12413 SUMMARY Objective: Patients with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy (JME) often present with risk-tak- ing behavior, suggestive of frontal lobe dysfunction. Recent studies confirm functional and microstructural changes within the frontal lobes in JME. This study aimed at char- acterizing decision-making behavior in JME and its neuronal correlates using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Methods: We investigated impulsivity in 21 JME patients and 11 controls using the Iowa Gambling Task (IGT), which measures decision making under ambiguity. Perfor- mance on the IGT was correlated with activation patterns during an fMRI working memory task. Results: Both patients and controls learned throughout the task. Post hoc analysis revealed a greater proportion of patients with seizures than seizure-free patients hav- ing difficulties in advantageous decision making, but no difference in performance between seizure-free patients and controls. Functional imaging of working memory networks showed that overall poor IGT performance was associated with an increased Dr. Wandschneider is activation in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) in JME patients. Impaired registrar in neurology learning during the task and ongoing seizures were associated with bilateral medial and is pursuing a PhD prefrontal cortex (PFC) and presupplementary motor area, right superior frontal at the UCL Institute of gyrus, and left DLPFC activation. Neurology. -

Ebook Download This Is Grime Ebook, Epub

THIS IS GRIME PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Hattie Collins | 320 pages | 04 Apr 2017 | HODDER & STOUGHTON | 9781473639270 | English | London, United Kingdom This Is Grime PDF Book The grime scene has been rapidly expanding over the last couple of years having emerged in the early s in London, with current grime artists racking up millions of views for their quick-witted and contentious tracks online and filling out shows across the country. Sign up to our weekly e- newsletter Email address Sign up. The "Daily" is a reference to the fact that the outlet originally intended to release grime related content every single day. Norway adjusts Covid vaccine advice for doctors after admitting they 'cannot rule out' side effects from the Most Popular. The awkward case of 'his or her'. Definition of grime. This site uses cookies. It's all fun and games until someone beats your h Views Read Edit View history. During the hearing, David Purnell, defending, described Mondo as a talented musician and sportsman who had been capped 10 times representing his country in six-a-side football. Fernie, aka Golden Mirror Fortunes, is a gay Latinx Catholic brujx witch — a combo that is sure to resonate…. Scalise calls for House to hail Capitol Police officers. Drill music, with its slower trap beats, is having a moment. Accessed 16 Jan. This Is Grime. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. More On: penn station. Police are scrambling to recover , pieces of information which were WIPED from records in blunder An unwillingness to be chained to mass-produced labels and an unwavering honesty mean that grime is starting a new movement of backlash to the oppressive systems of contemporary society through home-made beats and backing tracks and enraged lyrics. -

Special Issue

ISSUE 750 / 19 OCTOBER 2017 15 TOP 5 MUST-READ ARTICLES record of the week } Post Malone scored Leave A Light On Billboard Hot 100 No. 1 with “sneaky” Tom Walker YouTube scheme. Relentless Records (Fader) out now Tom Walker is enjoying a meteoric rise. His new single Leave } Spotify moves A Light On, released last Friday, is a brilliant emotional piano to formalise pitch led song which builds to a crescendo of skittering drums and process for slots in pitched-up synths. Co-written and produced by Steve Mac 1 as part of the Brit List. Streaming support is big too, with top CONTENTS its Browse section. (Ed Sheeran, Clean Bandit, P!nk, Rita Ora, Liam Payne), we placement on Spotify, Apple and others helping to generate (MusicAlly) love the deliberate sense of space and depth within the mix over 50 million plays across his repertoire so far. Active on which allows Tom’s powerful vocals to resonate with strength. the road, he is currently supporting The Script in the US and P2 Editorial: Paul Scaife, } Universal Music Support for the Glasgow-born, Manchester-raised singer has will embark on an eight date UK headline tour next month RotD at 15 years announces been building all year with TV performances at Glastonbury including a London show at The Garage on 29 November P8 Special feature: ‘accelerator Treehouse on BBC2 and on the Today Show in the US. before hotfooting across Europe with Hurts. With the quality Happy Birthday engagement network’. Recent press includes Sunday Times Culture “Breaking Act”, of this single, Tom’s on the edge of the big time and we’re Record of the Day! (PRNewswire) The Sun (Bizarre), Pigeons & Planes, Clash, Shortlist and certain to see him in the mix for Brits Critics’ Choice for 2018. -

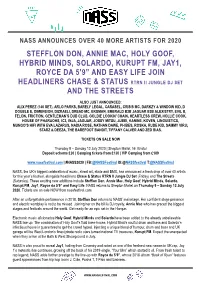

Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo

NASS ANNOUNCES OVER 40 MORE ARTISTS FOR 2020 STEFFLON DON, ANNIE MAC, HOLY GOOF, HYBRID MINDS, SOLARDO, KURUPT FM, JAY1, ROYCE DA 5’9” AND EASY LIFE JOIN HEADLINERS CHASE & STATUS RTRN II JUNGLE DJ SET AND THE STREETS ALSO JUST ANNOUNCED: ALIX PEREZ (140 SET), ARLO PARKS, BARELY LEGAL, CARASEL, CRISIS MC, DARKZY & WINDOW KID, D DOUBLE E, DIMENSION, DIZRAELI, DREAD MC, EKSMAN, EMERALD B2B JAGUAR B2B ALEXISTRY, EVIL B, FELON, FRICTION, GENTLEMAN’S DUB CLUB, GOLDIE LOOKIN’ CHAIN, HEARTLESS CREW, HOLLIE COOK, HOUSE OF PHARAOHS, IC3, INJA, JAGUAR, JOSSY MITSU, JUBEI, KANINE, KOVEN, LINGUISTICS, MUNGO’S HIFI WITH EVA LAZARUS, NADIA ROSE, NATHAN DAWE, PHIBES, ROSKA, RUDE KID, SAMMY VIRJI, STARZ & DEEZA, THE BAREFOOT BANDIT, TIFFANY CALVER AND ZED BIAS. TICKETS ON SALE NOW Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020 | Shepton Mallet, Nr. Bristol Deposit scheme £30 | Camping tickets from £130 | VIP Camping from £189 www.nassfestival.com | #NASS2020 | FB:@NASSFestival IG:@NASSfestival T:@NASSfestival NASS, the UK's biggest celebration of music, street art, skate and BMX, has announced a fresh drop of over 40 artists for this year’s festival, alongside headliners Chase & Status RTRN II Jungle DJ Set (Friday) and The Streets (Saturday). These exciting new additions include Stefflon Don, Annie Mac, Holy Goof, Hybrid Minds, Solardo, Kurupt FM, Jay1, Royce da 5’9” and Easy Life. NASS returns to Shepton Mallet on Thursday 9 – Sunday 12 July 2020. Tickets are on sale NOW from nassfestival.com After an unforgettable performance in 2018, Stefflon Don returns to NASS’ mainstage. Her confident stage presence and electric wordplay is not to be missed. -

Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play a Dissertation

The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play A dissertation presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Todd L. Harper November 2010 © 2010 Todd L. Harper. All Rights Reserved. This dissertation titled The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play by TODD L. HARPER has been approved for the School of Media Arts and Studies and the Scripps College of Communication by Mia L. Consalvo Associate Professor of Media Arts and Studies Gregory J. Shepherd Dean, Scripps College of Communication ii ABSTRACT HARPER, TODD L., Ph.D., November 2010, Mass Communications The Art of War: Fighting Games, Performativity, and Social Game Play (244 pp.) Director of Dissertation: Mia L. Consalvo This dissertation draws on feminist theory – specifically, performance and performativity – to explore how digital game players construct the game experience and social play. Scholarship in game studies has established the formal aspects of a game as being a combination of its rules and the fiction or narrative that contextualizes those rules. The question remains, how do the ways people play games influence what makes up a game, and how those players understand themselves as players and as social actors through the gaming experience? Taking a qualitative approach, this study explored players of fighting games: competitive games of one-on-one combat. Specifically, it combined observations at the Evolution fighting game tournament in July, 2009 and in-depth interviews with fighting game enthusiasts. In addition, three groups of college students with varying histories and experiences with games were observed playing both competitive and cooperative games together. -

Revista Gameblast - 15.Pdf

ÍNDICE De volta aos ringues O rei dos jogos de luta está prestes a tomar a atenção dos jogadores mais uma vez! Isso porque estamos a poucos dias do lançamento do ano da Capcom: Street Fighter V, a luta da noite aqui na Revista GameBlast. Para o aquecimento, vamos revisitar jogos e lutadores da franquia, além de muita coisa sobre o gênero dos jogos de luta. Nos intervalos, confira tudo sobre Mighty No.9, Far Cry Primal e muito mais! Boa leitura! – Rafael Neves BLAST FROM THE PAST Street Fighter III 3rd Strike (PS2) 04 DIRETOR GERAL / PROJETO GRÁFICO Sérgio Estrella PRÉVIA Street Fighter DIRETOR EDITORIAL V (Multi) 10 Rafael Neves DIRETOR DE PAUTAS Alberto Canen PRÉVIA João Pedro Meireles Lucas Pinheiro Silva Mighty No. 9 Pedro Vicente (Multi) 19 DIRETOR DE REVISÃO Alberto Canen PRÉVIA DIRETOR DE Far Cry Primal DIAGRAMAÇÃO (Multi) 25 Breno Madureira REDAÇÃO Dácio Augusto TOP 10 Ítalo Chianca July Dourado Melhores participações Renan Pinheiro em jogos de luta 31 REVISÃO Bruno Alves PERFIL Henrique Minatogawa Luigi Santana M. Bison (Street Fighter) 36 Vitor Tibério DIAGRAMAÇÃO Breno Madureira Bruno Italiani ANÁLISE David Vieira Guilherme Lima Resident Evil Zero Leandro Fernandes ONLINE HD Remaster (Multi) Letícia Fernandes ILUSTRAÇÕES ANÁLISE S. Carlos Sr. Raposo Pony Island (PC) ONLINE CAPA Felipe Araujo gameblast.com.br 2 ÍNDICE HQ Blast: Piada eterna... E receba todas as edições FAÇA SUA ASSINATURA em seu computador, smartphone ou tablet com antecedência, além de brindes, promoções GRÁTIS DA e edições bônus! REVISTA GAMEBLAST! ASSINAR! gameblast.com.br 3 BLAST FROM THE PAST por Renan Pinheiro Revisão: Henrique Minatogawa Diagramação: Bruno Italiani Street Fighter II chegou ao seu auge e quebrou a desconfiança dos fãs mais tradicionais com a inovação da barra de Super lançando a versão definitiva:Super Street Fighter II Turbo. -

Property Developers Leave Students in the Lurch

Issue1005.02.16 thegryphon.co.uk News p.5 TheGryphon speaks to University SecretaryRoger Gairabout PREVENTand tuitionfees Features p.10 Hannah Macaulayexplores the possible growth of veganism in 2016 [Image: 20th Century Fox] S [Image: AndyWhitton] Sport TheGryphon explores theincreasing In TheMiddle catchupwith p.19 Allthe lastestnewsand resultsfrom •similaritiesbetween sciencefiction •MysteryJetsbefore theirrecentgig thereturnofBUCSfixtures and reality p.17 at HeadrowHouse ITMp.4 [Image: Jack Roberts] Property Developers Leave Students In TheLurch accommodation until December 2015, parents were refusing to paythe fees for Jessica Murray and were informed that the halls would the first term of residence, or were only News Editor have abuilding certificate at this point. paying apercentage of the full rent owed. Property development companyPinna- According to the parent, whowishes to Agroup of Leeds University students cle Alliance have faced critcism for fail- remain anonymous, the ground floor of have also contacted TheGryphon after ing to complete building work on time, the accommodation wasstill completely they were forced in to finding new accom- leaving manystudents without accommo- unfinished and open to the elements, with modation in September due to their flat on dation or living in half finished develop- security guards patrolling the develop- 75 Hyde Park Road still being under de- ments. ment at all times to prevent break ins. velopment by Pinnacle. Pinnacle began development of Asquith Theparent also stated that the building Thethree students, whodonot wish to House and Austin Hall, twopurpose built had afire safety certificate for habitation be named, signed for the three-bedroom private halls of residence situated next to on the floors above the ground floor,but flat in March 2015, and they state that at Leodis, in January 2015, and students who afull building certificate had not been the end of July they were informed that the signed contracts were to move in Septem- signed off. -

Black Characters in the Street Fighter Series |Thezonegamer

10/10/2016 Black characters in the Street Fighter series |TheZonegamer LOOKING FOR SOMETHING? HOME ABOUT THEZONEGAMER CONTACT US 1.4k TUESDAY BLACK CHARACTERS IN THE STREET FIGHTER SERIES 16 FEBRUARY 2016 RECENT POSTS On Nintendo and Limited Character Customization Nintendo has often been accused of been stuck in the past and this isn't so far from truth when you... Aug22 2016 | More > Why Sazh deserves a spot in Dissidia Final Fantasy It's been a rocky ride for Sazh Katzroy ever since his debut appearance in Final Fantasy XIII. A... Aug12 2016 | More > Capcom's first Street Fighter game, which was created by Takashi Nishiyama and Hiroshi Tekken 7: Fated Matsumoto made it's way into arcades from around late August of 1987. It would be the Retribution Adds New Character Master Raven first game in which Capcom's golden boy Ryu would make his debut in, but he wouldn't be Fans of the Tekken series the only Street fighter. noticed the absent of black characters in Tekken 7 since the game's... Jul18 2016 | More > "The series's first black character was an African American heavyweight 10 Things You Can Do In boxer." Final Fantasy XV Final Fantasy 15 is at long last free from Square Enix's The story was centred around a martial arts tournament featuring fighters from all over the vault and is releasing this world (five countries to be exact) and had 10 contenders in total, all of whom were non year on... Jun21 2016 | More > playable. Each character had unique and authentic fighting styles but in typical fashion, Mirror's Edge Catalyst: the game's first black character was an African American heavyweight boxer. -

The A-Z of Brent's Black Music History

THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY BASED ON KWAKU’S ‘BRENT BLACK MUSIC HISTORY PROJECT’ 2007 (BTWSC) CONTENTS 4 # is for... 6 A is for... 10 B is for... 14 C is for... 22 D is for... 29 E is for... 31 F is for... 34 G is for... 37 H is for... 39 I is for... 41 J is for... 45 K is for... 48 L is for... 53 M is for... 59 N is for... 61 O is for... 64 P is for... 68 R is for... 72 S is for... 78 T is for... 83 U is for... 85 V is for... 87 W is for... 89 Z is for... BRENT2020.CO.UK 2 THE A-Z OF BRENT’S BLACK MUSIC HISTORY This A-Z is largely a republishing of Kwaku’s research for the ‘Brent Black Music History Project’ published by BTWSC in 2007. Kwaku’s work is a testament to Brent’s contribution to the evolution of British black music and the commercial infrastructure to support it. His research contained separate sections on labels, shops, artists, radio stations and sound systems. In this version we have amalgamated these into a single ‘encyclopedia’ and added entries that cover the period between 2007-2020. The process of gathering Brent’s musical heritage is an ongoing task - there are many incomplete entries and gaps. If you would like to add to, or alter, an entry please send an email to [email protected] 3 4 4 HERO An influential group made up of Dego and Mark Mac, who act as the creative force; Gus Lawrence and Ian Bardouille take care of business. -

Phonographic Performance Company of Australia Limited Control of Music on Hold and Public Performance Rights Schedule 2

PHONOGRAPHIC PERFORMANCE COMPANY OF AUSTRALIA LIMITED CONTROL OF MUSIC ON HOLD AND PUBLIC PERFORMANCE RIGHTS SCHEDULE 2 001 (SoundExchange) (SME US Latin) Make Money Records (The 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 100% (BMG Rights Management (Australia) Orchard) 10049735 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) Music VIP Entertainment Inc. Pty Ltd) 10065544 Canada Inc. (The Orchard) 441 (SoundExchange) 2. (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) NRE Inc. (The Orchard) 100m Records (PPL) 777 (PPL) (SME US Latin) Ozner Entertainment Inc (The 100M Records (PPL) 786 (PPL) Orchard) 100mg Music (PPL) 1991 (Defensive Music Ltd) (SME US Latin) Regio Mex Music LLC (The 101 Production Music (101 Music Pty Ltd) 1991 (Lime Blue Music Limited) Orchard) 101 Records (PPL) !Handzup! Network (The Orchard) (SME US Latin) RVMK Records LLC (The Orchard) 104 Records (PPL) !K7 Records (!K7 Music GmbH) (SME US Latin) Up To Date Entertainment (The 10410Records (PPL) !K7 Records (PPL) Orchard) 106 Records (PPL) "12"" Monkeys" (Rights' Up SPRL) (SME US Latin) Vicktory Music Group (The 107 Records (PPL) $Profit Dolla$ Records,LLC. (PPL) Orchard) (SME US Latin) VP Records - New Masters 107 Records (SoundExchange) $treet Monopoly (SoundExchange) (The Orchard) 108 Pics llc. (SoundExchange) (Angel) 2 Publishing Company LCC (SME US Latin) VP Records Corp. (The 1080 Collective (1080 Collective) (SoundExchange) Orchard) (APC) (Apparel Music Classics) (PPL) (SZR) Music (The Orchard) 10am Records (PPL) (APD) (Apparel Music Digital) (PPL) (SZR) Music (PPL) 10Birds (SoundExchange) (APF) (Apparel Music Flash) (PPL) (The) Vinyl Stone (SoundExchange) 10E Records (PPL) (APL) (Apparel Music Ltd) (PPL) **** artistes (PPL) 10Man Productions (PPL) (ASCI) (SoundExchange) *Cutz (SoundExchange) 10T Records (SoundExchange) (Essential) Blay Vision (The Orchard) .DotBleep (SoundExchange) 10th Legion Records (The Orchard) (EV3) Evolution 3 Ent.