Mari and the Minoans*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cutting-Edge Technology and Know-How of Minoans/Mycenaeans During Lba and Possible Implications for the Dating of the Trojan War

TAL 46-47 -pag 51-80 (-03 GIANNIKOS):inloop document Talanta 05-06-2016 14:31 Pagina 51 TALANTA XLVI-XLVII (2014-2015), 51 - 79 CUTTING-EDGE TECHNOLOGY AND KNOW-HOW OF MINOANS/MYCENAEANS DURING LBA AND POSSIBLE IMPLICATIONS FOR THE DATING OF THE TROJAN WAR Konstantinos Giannakos In the present paper, the material evidence, in LBA, both for the technological level of Minoan/Mycenaean Greece, mainland-islands-Crete, and the image emerging from the archaeological finds of the wider area of Asia Minor, Land of Ḫatti, Cyprus, and Egypt, are combined in order to draw conclusions regard- ing international relations and exchanges. This period of on the one hand pros- perity with conspicuous consumption and military expansion, on the other hand as well of decline and degradation of power are considered in relation with the ability of performing overseas raids of Mycenaean Greeks. The finds of the destructions’ layers in Troy VI/VIIa are examined in order to verify whether one of these layers is compatible to the Trojan War, while an earlier dating is pro- posed. The results are compared with the narrative of ancient literature in order to trace compatibilities or inconsistencies to the archaeological finds. Introduction Technology and its ‘products’, when unearthed by archaeologists, are irrefutable witnesses to the technological level of each era and place. Especially the cut- ting-edge technology and, more in general, an advanced know-how are, in my opinion, of decisive importance, since “Great Powers” use them in order to increase wealth and military superiority. The evaluation of archaeological finds, cutting-edge technology, and advanced know-how of each era could result in conclusions regarding the nature of international trade and relation- ships, and can also be brought in connection with evidence from ancient litera- ture. -

Linguistic Study About the Origins of the Aegean Scripts

Anistoriton Journal, vol. 15 (2016-2017) Essays 1 Cretan Hieroglyphics The Ornamental and Ritual Version of the Cretan Protolinear Script The Cretan Hieroglyphic script is conventionally classified as one of the five Aegean scripts, along with Linear-A, Linear-B and the two Cypriot Syllabaries, namely the Cypro-Minoan and the Cypriot Greek Syllabary, the latter ones being regarded as such because of their pictographic and phonetic similarities to the former ones. Cretan Hieroglyphics are encountered in the Aegean Sea area during the 2nd millennium BC. Their relationship to Linear-A is still in dispute, while the conveyed language (or languages) is still considered unknown. The authors argue herein that the Cretan Hieroglyphic script is simply a decorative version of Linear-A (or, more precisely, of the lost Cretan Protolinear script that is the ancestor of all the Aegean scripts) which was used mainly by the seal-makers or for ritual usage. The conveyed language must be a conservative form of Sumerian, as Cretan Hieroglyphic is strictly associated with the original and mainstream Minoan culture and religion – in contrast to Linear-A which was used for several other languages – while the phonetic values of signs have the same Sumerian origin as in Cretan Protolinear. Introduction The three syllabaries that were used in the Aegean area during the 2nd millennium BC were the Cretan Hieroglyphics, Linear-A and Linear-B. The latter conveys Mycenaean Greek, which is the oldest known written form of Greek, encountered after the 15th century BC. Linear-A is still regarded as a direct descendant of the Cretan Hieroglyphics, conveying the unknown language or languages of the Minoans (Davis 2010). -

The Role of the Philistines in the Hebrew Bible*

Teresianum 48 (1997/1) 373-385 THE ROLE OF THE PHILISTINES IN THE HEBREW BIBLE* GEORGE J. GATGOUNIS II Although hope for discovery is high among some archeolo- gists,1 Philistine sources for their history, law, and politics are not yet extant.2 Currently, the fullest single source for study of the Philistines is the Hebrew Bible.3 The composition, transmis sion, and historical point of view of the biblical record, however, are outside the parameters of this study. The focus of this study is not how or why the Hebrews chronicled the Philistines the way they did, but what they wrote about the Philistines. This study is a capsule of the biblical record. Historical and archeo logical allusions are, however, interspersed to inform the bibli cal record. According to the Hebrew Bible, the Philistines mi * Table of Abbreviations: Ancient Near Eastern Text: ANET; Biblical Archeologist: BA; Biblical Ar- cheologist Review: BAR; Cambridge Ancient History: CAH; Eretz-Israel: E-I; Encyclopedia Britannica: EB; Journal of Egyptian Archeology: JEA; Journal of Near Eastern Studies: JNES; Journal of the Study of the Old Testament: JSOT; Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly Statement: PEFQSt; Vetus Testamentum: VT; Westminster Theological Journal: WTS. 1 Cf. Law rence S tager, “When the Canaanites and Philistines Ruled Ashkelon,” BAR (Mar.-April 1991),17:36. Stager is hopeful: When we do discover Philistine texts at Ashkelon or elsewhere in Philistia... those texts will be in Mycenaean Greek (that is, in Linear B or same related script). At that moment, we will be able to recover another lost civilization for world history. -

The Early History of Syria and Palestine

THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON Gbe Semitic Series THE EARLY HISTORY OF SYRIA AND PALESTINE By LEWIS BAYLES PATON : SERIES OF HAND-BOOKS IN SEM1T1CS EDITED BY JAMES ALEXANDER CRAIG PROFESSOR OF SEMITIC LANGUAGES AND LITERATURES AND HELLENISTIC GREEK, UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN Recent scientific research has stimulated an increasing interest in Semitic studies among scholars, students, and the serious read- ing public generally. It has provided us with a picture of a hitherto unknown civilization, and a history of one of the great branches of the human family. The object of the present Series is to state its results in popu- larly scientific form. Each work is complete in itself, and the Series, taken as a whole, neglects no phase of the general subject. Each contributor is a specialist in the subject assigned him, and has been chosen from the body of eminent Semitic scholars both in Europe and in this country. The Series will be composed of the following volumes I. Hebrews. History and Government. By Professor J. F. McCurdy, University of Toronto, Canada. II. Hebrews. Ethics arid Religion. By Professor Archibald Duff, Airedale College, Bradford, England. [/« Press. III. Hebrews. The Social Lije. By the Rev. Edward Day, Springfield, Mass. [No7i> Ready. IV. Babylonians and Assyrians, with introductory chapter on the Sumerians. History to the Fall of Babylon. V. Babylonians and Assyrians. Religion. By Professor J. A. Craig, University of Michigan. VI. Babylonians and Assyrians. Life and Customs. By Professor A. H. Sayce, University of Oxford, England. \Noiv Ready. VII. Babylonians and Assyrians. -

The Philistines Were Among the Sea Peoples, Probably of Aegean Origin, Who First Appeared in the E Mediterranean at the End of the 13Th Century B.C

The Philistines were among the Sea Peoples, probably of Aegean origin, who first appeared in the E Mediterranean at the end of the 13th century B.C. These peoples were displaced from their original homelands as part of the extensive population movements characteristic of the end of the LB Age. During this period, the Egyptians and the Hittites ruled in the Levant, but both powers were in a general state of decline. The Sea Peoples exploited this power vacuum by invading areas previously subject to Egyptian and Hittite control, launching land and sea attacks on Syria, Palestine, and Egypt, to which various Egyptian sources attest. The various translations of the name Philistine in the different versions of the Bible reveal that even in early times translators and exegetes were unsure of their identity. In the LXX, for example, the name is usually translated as allopsyloi ("strangers"), but it occurs also as phylistieim in the Pentateuch and Joshua. In the Hebrew Bible, the Philistines are called Pelishtim, a term defining them as the inhabitants ofPeleshet, i.e., the coastal plain of S Palestine. Assyrian sources call them both Pilisti and Palastu. The Philistines appear as prst in Egyptian sources. Encountering the descendants of the Philistines on the coast of S Palestine, the historian Herodotus, along with sailors and travelers from the Persian period onward called them palastinoi and their countrypalastium. The use of these names in the works of Josephus, where they are common translations forPhilistines and Philistia and, in some cases, for the entire land of Palestine, indicates the extent to which the names had gained acceptance by Roman times. -

The Philistines and the "Sea Peoples" Not the Same Entity

THE PHILISTINES AND THE "SEA PEOPLES" NOT THE SAME ENTITY We have already indicated the opinion of Rowley and others1 who believe that the mention of the Philistines in the Bible proves the Exodus occurred after the Philistines settled in the land. Since it is generally considered that they settled about the period of Raamses III,2 we are accordingly obliged to date the Exodus about 1100 B. C. This dating condenses the whole period of the wandering in the desert, the conquest of Canaan the period of the judges as well as Saul's reign into a time–lapse of about 50–80 years3. Such an estimate is in complete contradiction with the biblical narrative. Some scholars try to settle this difficulty by stating that the Philistines settled in the land several generations after the Israelite conquest,4 and their mention in the patriarchal period is anachronistic. Those scholars who so vehemently reject the possibility of anachronism when dealing with Raamses, are prepared without hesitation to accept such a possibility with the name "Philistines". The view which holds that the Philistines Settlement occurred at a late historical period is based on various factors. The Bible calls "Caphtor' the original Philistine homeland, and regards them as being of Egyptian descent: "And Mizrayim (=Egypt) begot Ludim, and Anamim, and Lehavim and Naftuhim, and Patrusim and Kasluhim (out of whom came Pelishtim) and Kaftorim"(Gen. 10: 13–14). Elsewhere Caphtor is mentioned as "Iy – is understood to signify "אי – Jer. 47: 4). The word "Iy אי כפתור) "Caphtor 1 Petrie, Palestine and Israel, p. -

CAPHTOR-CAPPADOCIA by G. A. WAINWRIGHT Bournemouth Today the Standard Belief Is That Caphtor Was Crete, Though Biblical Scholars

CAPHTOR-CAPPADOCIA BY G. A. WAINWRIGHT Bournemouth Today the standard belief is that Caphtor was Crete, though Biblical scholars have always noted the difficulties. In fact that island is only one of many places which have been proposed as the site. Thus, Cyprus, Phoenicia and the Phoenician colonies, and even the island of Karpathos have also been suggested, and quite recently though "with the utmost reserve" the island of Kythera 1), while of course Cappadocia, unreasonable as it has seemed hitherto, had to be in- cluded in the list. In this article much evidence is brought forward to show that Cappadocia, or more accurately a part of Greater Cappa- docia, was indeed Caphtor 2). Of all the various countries suggested Crete has received the main support, because it was accepted that Caphtor was described as an "island" in the O.T., and Crete is a large one. Since the early years of this century the belief in Crete has been further strengthened by Sir Arthur EVANS' discovery that it was also the home of a splendid civilization. There was a country known to the Egyptians as Keftiu, or as it may have been pronounced Kefto, and this is evidently the same name as the contemporary cuneiform Kaptara, and the much later Hebrew Caphtor, though the absence of the final r has never been explained. Hence, based on the above-mentioned firm belief, there has grown up a strongly held view that Keftiu was also Crete. This idea was 1) WEIDNERin J. H. S., LIX (1939), p. 138. 2) I approached this question in an article entitled "Caphtor, Keftiu and Cappa- docia" published in 1931, p. -

Noah's Flood ? It Has Been Shown That None of These Floods Covered Entire Mesopotamia Not Even a Whole City

NOAH’s Flood In Bible, Quran and Mesopotamian Stories. By MUNIR AHMED KHAN Address: 108-A, Block 13-C, Gulshan-e-Iqbal, Karachi, PAKISTAN. Ph: 92-21-4967500. VOLUME I Noah, Flood and his Ark in Biblical Literature and Near eastern parallels of flood stories. Index Foreword Part I: Overview: Chapter 1: Story of Bible and Quran; Search for Archaeological proof of flood and remains of Ark; Mesopotamian parallels and other Near Eastern stories; Flood stories from around the world, Sightings of Ark and search on Ararat; Place and time of event. Verification of Flood story; Quran’s version; Is the story rational and logical. Is there need for a fresh appraisal? Part II: Flood stories: Biblical, Mesopotamian and other Near Eastern Flood Stories; Quran’s story of Noah’s flood. Stories from other parts of world. Chapter 2: Genesis Flood story and its context. A: Primeval story: Components of Primeval story. B: Patriarchal story; Components of Patriarchal story. Chapter 3: Other Biblical Sources. NOAH in New Testament; Other sources: Josephus; Book of Jubilees; Sibylline Oracles; Legends of Jews; Dead Sea Scrolls. Chapter 4: Mesopotamian parallels: Parallels of Pre-flood stories; Flood stories; 1.Sumerian Myth of Ziusudra: The story of Deluge; 2.Myth of Atrahasis. 3. Utnapishtim in Epic of Gilgamesh. Chapter 5: Other Near Eastern accounts: Chaldee Account of Berosus; Other Mesopotamian accounts Armenian stories; Greek story; Hittite and Hurrian texts. Chapter 6: Quran’s story of Noah’s Flood Chapter 7: Other flood stories of world: Indian Flood Story; Chinese story. Part III: Analysis of Biblical and Mesopotamian stories Chapter 8: Relation of Primeval and Patriarchal stories of Genesis. -

An Up-To-Date Account of the Minoan Connection with the Philistine

‘ALL THE CHERETHITES, AND ALL THE PELETHITES, AND ALL THE GITTITES (SAMUEL 2:15-18)’ – AN UP-TO-DATE ACCOUNT OF THE MINOAN CONNECTION WITH THE PHILISTINE Louise A. Hitchcock INTRODUCTION The ethnonyms Cherethite and Pelethite, and associations of the Philistines with Caphtor in the Old Testament point to a Cretan origin for them in literary tradition (Finkelstein 2002; Machinist 2000).1 This tradition, combined with the well-known Philistine production of Mycenaean style pottery,2 has been criticized by those reluctant to simplistically associate pots with peoples.3 Additional categories of evidence indicating an Aegean origin for the Philistines are well rehearsed. My contribution reviews the current state of understanding of the specific links between the Aegean and Philistia with regard to recent research, and with special reference to Crete. I will briefly discuss ritual action, contextual analysis, architecture, administrative practices, inscriptions, and methodology. Using a transcultural approach (Hitchcock 2011), it is proposed that some aspects of Minoan culture survived in Philistia, embedded among other cultural components associated with the Mycenaeans, Cypriots, Anatolians, and Canaanites. It is with great pleasure I present this contribution to Aren Maeir who I regard as a close friend, mentor, and collaborator.4 HISTORICAL LINK BETWEEN CRETE AND PHILISTIA As Deuteronomistic history was not written down prior to the 7th century BCE any description of pre-eighth century events would have been taken from oral histories and cultural memory, and then adapted to suit the agendas of later writers (Finkelstein 2002).5 For example, Finkelstein (2002: 148-50) argued that references to Cherethite and Pelethite were based on accounts of 7th century Greek mercenaries in Egypt and projected backwards in order to glorify the Davidic reign. -

Rutgers University the Sea People and Their Migration

RUTGERS UNIVERSITY THE SEA PEOPLE AND THEIR MIGRATION PRESENTING AN HONORS THESIS THAT HAS BEEN SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE RUTGERS UNIVERSITY HISTORY DEPARTMENT. BY SHELL PECZYNSKI NEW BRUNSWICK, NEW JERSEY MARCH 2009 Acknowledgments I want to thank the matriarchs of my family for believing that, as a woman, I could do anything; Professor Cargill for luring me to Rutgers University with his class syllabus of the Ancient Near East course and subsequent courses on Greece. I also need to mention Professor Tannus for planting the seed in my mind of actually doing a thesis paper. I would also like to thank Tom Andruszewski for taking the first step into the deep dark waters of thesis writing and surviving the swim, encouraging me not to drown in the process, and that it can also be done by those of us who work full time. I cannot forget Shanna and Marion; my smart life-long friends who have inspired me and helped me through the rough patches with their computer knowledge and multi-tasking skills. These women inspired me to take the leap into the dark sea of higher education. Which leads me to my mentor Dr. Figueira, whose lecturing of mythology struck me with the epiphany that I want to someday tell the stories of the ancients and inspire our youth in such a way that I can mirror his brilliance in the unrehearsed flow and clarity of the lectures and tangents we may go on. His eloquence of speech and knowledge of diverse histories is colorful and vibrant, lacking the dryness of some historical topics and generic monotone speaking of many historians. -

Reconsidering Ancient Egyptian Perceptions of Ethnicity

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2014 Noticing neighbors: reconsidering ancient Egyptian perceptions of ethnicity Taylor Bryanne Woodcock Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Woodcock, T. (2014).Noticing neighbors: reconsidering ancient Egyptian perceptions of ethnicity [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/905 MLA Citation Woodcock, Taylor Bryanne. Noticing neighbors: reconsidering ancient Egyptian perceptions of ethnicity. 2014. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/905 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Noticing Neighbors: Reconsidering Ancient Egyptian Perceptions of Ethnicity A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Psychology, and Egyptology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In Egyptology By Taylor Bryanne Woodcock Under the supervision of Dr. Mariam Ayad May 2014 ABSTRACT Ethnic identities are nuanced, fluid and adaptive. They are a means of categorizing the self and the ‘other’ through the recognition of geographical, cultural, lingual, and physical differences. This work examines recurring associations, epithets and themes in ancient Egyptian texts to reveal how the Egyptians discussed the ethnic uniqueness they perceived of their regional neighbors. It employs Egyptian written records, including temple inscriptions, royal and private correspondence, stelae and tomb autobiographies, and literary tales, from the Old Kingdom to the beginning of the Third Intermediate Period. -

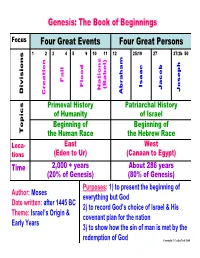

Four Great Persons Four Great Events Genesis: the Book of Beginnings

Genesis: The Book of Beginnings Focus Four Great Events Four Great Persons 1 2 3 4 5 9 10 11 12 25:19 27 37:2b 50 Fall Isaac Flood (Babel) Jacob Nations Joseph Divisions Abraham Creation Primeval History Patriarchal History of Humanity of Israel Beginning of Beginning of Topics the Human Race the Hebrew Race Loca- East West tions (Eden to Ur) (Canaan to Egypt) Time 2,000 + years About 286 years (20% of Genesis) (80% of Genesis) Purposes : 1) to present the beginning of Author: Moses everything but God Date written: after 1445 BC 2) to record God’s choice of Israel & His Theme: Israel’s Origin & covenant plan for the nation Early Years 3) to show how the sin of man is met by the redemption of God Copyright © Cecilia Perh 2004 The Ark landed in the “mountains of Ararat” in the Middle East (Gen 8:4), which is located between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea in modern Turkey. After leaving the Ark, most if not all of Noah’s early descendants migrated to the land of Shinar, or Mesopotamia, or Babylonia as it eventually became known & dwelt there. Tower of Babel Dispersion High Culture “At the dispersion of peoples out from the area of the Tower of Babel, the first wave of migrants suffered culture loss. These peripheral cultures would today be termed “primitive” when in actuality they were anything but primitive, & should be viewed Copyright © Cecilia Perh 2004 as de-cultured” Donald E. Chittick 2Tim2-2.com http://www.gty.org/resources.php?sectio n=transcripts&aid=231772 - edited We descended from the family of Noah, whose three sons of Noah populated the whole earth.