7 Book Review, Iqbal Chawla

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

O'zbekiston Respublikasi Xalq Ta'limi Vazirligi

O’ZBEKISTON RESPUBLIKASI XALQ TA’LIMI VAZIRLIGI A. QODIRIY NOMLI JIZZAX DAVLAT PEDAGOGIKA INTSITUTI TABIATSHUNOSLIK VA GEOGRAFIYA FAKULTETI GEOGRAFIYA VA UNI O’QITISH METODIKASI KAFEDRASI O’RTA OSIYO TABIIY GEOGRAFIYASI FANIDAN REFARAT MAVZU: TURON PASTTEKISLIGI. BAJARDI: 307 – GURUH TALABASI ABDULLAYEVA M QABUL QILDI: o’qituvchi: G. XOLDOROVA JIZZAX -2013 1 R E J A: Kirish I. Bob. Turon pasttekisligining tabiiy geografik tavsifi. 1.1. Geografik o’rni va rel’efi 1.2. Iqlimiy xususiyatlari. 1.3. Tuproqlari, o’simlik va hayvonot dunyosi. II. Bob. Turon pasttekisligining hududiy tavsifi. 2.1. Qizilqum va Qoraqum. 2.2. To’rg’ay Mug’ojar. 2.3. Mang’ishloq Ustyurt. Xulosa. Foydalanilgan adabiyotlar. 2 3 4 5 KIRISH. Tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirish deganda xududlarni ularni tabiiy geografik hususiyatlariga qarab turli katta-kichiklikdagi regional birliklarga ajratish tushuniladi. Tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirishda mavjud bo’lgan va taksonamik jihatdan bir-biri bilan bog’liq regional tabiiy geografik komplekislar ajratiladi, har-bir komplekis tabiatning o’ziga xos hususiyatlarini ochib beradi ular tabiatni tasvirlaydi hamda haritaga tushuriladi. Tabiiy geografik region nafaqat tabiiy sharoiti bilan balki o’ziga xos tabiiy resurslari bilan ham boshqalardan ajralib turadi. Shuning uchun tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirish har-bir hududning o’ziga xos sharoiti va reurslarini boxolashga imkon beradi. Uning ilmiy va amaliy ahamiyati, ayniqsa hozirgi vaqtda tabiatda ekologik muozanatni saqlash va ekologik muomolarni oldini olish dolzarb masala bo’lib turganda, juda kattadir. Tabiiy geografik rayonlashtirishni taksonamik birliklar sistemasi asosida amalgam oshirish mumkin. O’rta Osiyo hududini rayonlashtirish bilan ko’p olimlar shug’ulangan. Ular dastlab tarmoq tabiiy geografik; geomarfologik, iqlimiy, tuproqlar geografiyasi, geobatanik va zoogeografik rayonlashtirishga etibor berganlar. -

The Decline of Buddhism in India

The Decline of Buddhism in India It is almost impossible to provide a continuous account of the near disappearance of Buddhism from the plains of India. This is primarily so because of the dearth of archaeological material and the stunning silence of the indigenous literature on this subject. Interestingly, the subject itself has remained one of the most neglected topics in the history of India. In this book apart from the history of the decline of Buddhism in India, various issues relating to this decline have been critically examined. Following this methodology, an attempt has been made at a region-wise survey of the decline in Sind, Kashmir, northwestern India, central India, the Deccan, western India, Bengal, Orissa, and Assam, followed by a detailed analysis of the different hypotheses that propose to explain this decline. This is followed by author’s proposed model of decline of Buddhism in India. K.T.S. Sarao is currently Professor and Head of the Department of Buddhist Studies at the University of Delhi. He holds doctoral degrees from the universities of Delhi and Cambridge and an honorary doctorate from the P.S.R. Buddhist University, Phnom Penh. The Decline of Buddhism in India A Fresh Perspective K.T.S. Sarao Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd. ISBN 978-81-215-1241-1 First published 2012 © 2012, Sarao, K.T.S. All rights reserved including those of translation into other languages. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form, or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written permission of the publisher. -

Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist

DHARMA KINGS AND FLYING WOMEN: BUDDHIST EPISTEMOLOGIES IN EARLY TWENTIETH-CENTURY INDIAN AND BRITISH WRITING by CYNTHIA BETH DRAKE B.A., University of California at Berkeley, 1984 M.A.T., Oregon State University, 1992 M.A. Georgetown University, 1999 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of English 2017 This thesis entitled: Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist Epistemologies in Early Twentieth-Century Indian and British Writing written by Cynthia Beth Drake has been approved for the Department of English ________________________________________ Dr. Laura Winkiel __________________________________________ Dr. Janice Ho Date ________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. Drake, Cynthia Beth (Ph.D., English) Dharma Kings and Flying Women: Buddhist Epistemologies in Early Twentieth-Century Indian and British Writing Thesis directed by Associate Professor Laura Winkiel The British fascination with Buddhism and India’s Buddhist roots gave birth to an epistemological framework combining non-dual awareness, compassion, and liberational praxis in early twentieth-century Indian and British writing. Four writers—E.M. Forster, Jiddu Krishnamurti, Lama Yongden, and P.L. Travers—chart a transnational cartography that mark points of location in the flow and emergence of this epistemological framework. To Forster, non- duality is a terrifying rupture and an echo of not merely gross mismanagement, but gross misunderstanding by the British of India and its spiritual legacy. -

Buddhism and Gandhi Philosophy.And Praxis

1 ''>~.,.~r-..;.,, __,,,, -- ~ ... Philosophy ~ nitm111p of Jllumba, Buddhism and Gandhi Philosophy.and Praxis [An Anthology of Scholarly articles on Buddhism and Gandhi: Philosophy and Praxis from the 35th Session of the Maharashtra Tattvajnana Perished] Editors: Arehano Malik-Goure and Meenal l<atamikar ~, A t)Ov1 Maharashtra Tattvajnano Parlshad C •Kr-~ IJ \ :J1,,, .,.. t.:-- , .r,,, ; "'$/X)•t.,, Jy r ,01 ~l•t"n<Jro 8vrlnqay Pro f. MP lt'ro'-" P.•c-,' C 'r ~~('"Qr-,--: e ►'·cl S S A"'' o•, O' Pi o / s H 0 1xi1 0 11cJ monv m o re . "' l...' r( t, · • 'Our\(_;n') l'Y', ,....~" O''d Ir-,., n'O "'I Qft,/1,' P ,('I\ o f llll) ' Pori\ l'lOd' The me" o ""· c' "'<' Pc, nod .,,. 1, ·c ... on~ .x.. f1.1CL'''' •1c•crrw,q o l und rc:H•o rc h ,n i, •: SUl,,:,c l C ' c,rdosoo..-,., " '.'v·otn Cl ~ (l rn Iv l)( Q \ 1( !(1 plo rlorn, fo r 1110 d isc us ~'ll, ,n rr--~on. ·op ,:,n~~ ·c lt1t.' D '"1\0()11~1,JI l1.•rofu r o concJv c1vt• lor ~oc iol l rorrlo,11"\Qt r r G~ (:'lv'"l "'H ('n() l>v O ',) l)fldt'Jn bc, tw('l(1n !ho ocodom,c,on o r,d 'r,c rnor.- ••1 ~ c •o .nc ~«:01,• '''C""'\' ,, nt'I :_)',_ ophy o n1ong a ll c ,111e ns. 1he 1 o r hcd cllg~,w;~ 'Ol'IOI , , • ... · ,-., f()I tlC con,pf,sh,ng fh C'.>O gool~. 11 ,s doing o n ,,c- •r-c, o •: ' 01,1 o · :YtnQ.;nu ..,,,. -

Sparrow Provider Network Directory

SPN1 Sparrow Provider Network Directory Published: 08/25/2021 PHPMichigan.com PHYSICIANS HEALTH PLAN P.O. Box 30377 Lansing, MI 48909-7877 517.364.8400 or 800.562.6197 This directory will help you find an in-network Physician/Practitioner/Provider. For a complete description of services and benefits, please refer to your Certificate of Coverage. You are responsible to verify the participation status of the Physician/Practitioner, Hospital or other Provider before you receive health services. You must show your Member ID card every time you request Health Coverage. You may contact Physicians Health Plan's (PHP) Network Services Department at 517.364.8312 or 800.562.6197 for additional information regarding Physician/Practitioner/Provider credentials (including Medical School, Residency, Board Certification and Accreditation status). Information may also be found on PHP’s website at PHPMichigan.com. This includes primary hospital privileges, office hours and whether they are accepting new Patients. This website houses the most current information. A board certified Physician (MD or DO) has completed an approved educational training program (residency training) and an evaluation process including an examination designed to assess the knowledge, skills and experience necessary to provide quality patient care in that specialty. There are two certifying umbrella organizations: the American Board of Medical Specialties (http://www.abms.org/) and the Bureau of Osteopathic Specialists and Boards of Certification (https://certification.osteopathic.org/bureau-of-osteopathic-specialists/). PHP reimburses Physicians/Practitioners/Providers a fee for each service rendered. If you would like to understand more about the payment methods used for reimbursement, please call the Network Services Department at 517.364.8312 or 800.562.6197. -

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region

Water Resources Lifeblood of the Region 68 Central Asia Atlas of Natural Resources ater has long been the fundamental helped the region flourish; on the other, water, concern of Central Asia’s air, land, and biodiversity have been degraded. peoples. Few parts of the region are naturally water endowed, In this chapter, major river basins, inland seas, Wand it is unevenly distributed geographically. lakes, and reservoirs of Central Asia are presented. This scarcity has caused people to adapt in both The substantial economic and ecological benefits positive and negative ways. Vast power projects they provide are described, along with the threats and irrigation schemes have diverted most of facing them—and consequently the threats the water flow, transforming terrain, ecology, facing the economies and ecology of the country and even climate. On the one hand, powerful themselves—as a result of human activities. electrical grids and rich agricultural areas have The Amu Darya River in Karakalpakstan, Uzbekistan, with a canal (left) taking water to irrigate cotton fields.Upper right: Irrigation lifeline, Dostyk main canal in Makktaaral Rayon in South Kasakhstan Oblast, Kazakhstan. Lower right: The Charyn River in the Balkhash Lake basin, Kazakhstan. Water Resources 69 55°0'E 75°0'E 70 1:10 000 000 Central AsiaAtlas ofNaturalResources Major River Basins in Central Asia 200100 0 200 N Kilometers RUSSIAN FEDERATION 50°0'N Irty sh im 50°0'N Ish ASTANA N ura a b m Lake Zaisan E U r a KAZAKHSTAN l u s y r a S Lake Balkhash PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC Ili OF CHINA Chui Aral Sea National capital 1 International boundary S y r D a r Rivers and canals y a River basins Lake Caspian Sea BISHKEK Issyk-Kul Amu Darya UZBEKISTAN Balkhash-Alakol 40°0'N ryn KYRGYZ Na Ob-Irtysh TASHKENT REPUBLIC Syr Darya 40°0'N Ural 1 Chui-Talas AZERBAIJAN 2 Zarafshan TURKMENISTAN 2 Boundaries are not necessarily authoritative. -

Honor Roll Stories of Honor

THE FOUNDATION for BARNES-JEWISH HOSPITAL Honor Roll Stories of Honor A Legacy of Giving 3 A Focus on Community Health 5 A Fight of a Lifetime 7 A Symbol of Hope 9 Honor Roll 10 Tribute Gifts 40 2019 2019: AN AMAZING YEAR ROLL HONOR Each year in our Honor Roll, we have the privilege Installed Patrick White, MD, as the inaugural Stokes to recognize the incredible people in our community, Family Endowed Chair in Palliative Medicine and throughout the country and around the world who come Supportive Care, representing a new department at together for one common cause: to enrich lives, save Washington University School of Medicine that is lives and transform health care through charitable gifts working to transform the way we think about end-of- to The Foundation for Barnes-Jewish Hospital. life care and living with chronic and painful diseases. We are honored to take this opportunity to tell the stories Awarded nearly 150 scholarships at Goldfarb School of our donors who were inspired by the exceptional, of Nursing to the future nurses who are so critical to compassionate care they received. These stories are about the health and well-being of patients in our community. the tradition of giving and community service, as well as inspiring courage and eternal optimism in the face Raised more than $4 million at the annual of challenging circumstances. They epitomize what we Illumination Gala to support innovative research know to be true about our donors: that individuals have at Siteman Cancer Center. the power to change the world around them for the better. -

Qaraqalpaq Tilinin Imla Sqzligi

QARAQALPAQ TILININ IMLA SQZLIGI Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasi Xaliq bilimlendiriw ministrligi tarepinen tastiyiqlangan NOKIS «BILIM» 2017 Oaraaalpaq tiling imla sozlig.. Uliwma UOK: 811.512.121-35(076.3)------------- ■ S 4 bcrctug.n mektepoqiwshihn KBK: 81.2 Q ar b.um Nokis, «B.I.m» baSpaSl, Q 51 2017-jil- 348 bet. UOK: 8X1.512-121-35 (076.3) KBK: 81.2 Qar Q—51 Diiziwshiler: Madenbay Dawletov Shamshetdin Abdinazimov, Aruxan Dawletova Pikir bildiriwshiler: n.Sevdallaeva. - Filologiya ilimleriniP kandIdaiti Z. Ismaylova - Qaraqalpaqstan RespAlikasXaliq bilimlendmw ministrliginin jetekshi qanigesi. QARAQALPAQ TILININ IMLA SOZLIGI Nokis —«Bilim» — 2017 Redaktorlar S. Aytmuratova, S. Baynazarova Kork.redaktor I. Serjanov Tex. redakton B. Tunmbetov Operatorlar N. Saukieva, A. Begdullaeva Original-maketten basiwga ruqsat etilgen waqti 30.10.2017-j. Formati 60x90 '/]6. Tip «Tayms» garniturasi. Kegl 12. Ofset qagazi. Ofset baspa usilinda basildi. Kolemi 21,75 b.t. 22,6 esap b.t. Nusqasi 4000 dana. Buyirtpa № 17-677. «Bilim» baspasi. 230103. Nokis qalasi, Qaraqalpaqstan koshesi, 9. «0‘zbekiston» baspa-poligrafiyaliq doretiwshilik uyi. Tashkent, «Nawayi» koshesi, 30. © M.Dawletov ham t.b., 2017. ISBN 978-9943-4442-0-1 © «Bilim» baspasi, 2017. QARAQALPAQSTAN RESPUBLIKASI MINISTRLER KENESININ QARARl 224-san. 2016-jil 5-iyul Nokis qalasi QARAQALPAQ TILININ TIYKARGI IMLA QAGIYDALARIN TASTIYIQLAW HAQQINDA Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasi Joqargi Kenesinin 2016-jil 10-iyunde qabil etilgen «Qaraqalpaqstan Respublikasimn ayinm nizamlanna ozgerisler ham qosimshalar kirgiziw haqqinda»gi 91/IX sanli qarann onnlaw maqsetinde Ministrler Kenesi qarar etedi: 1. Latin jaziwina tiykarlangan Qaraqalpaq tiliniri tiykargi imla qagiydalar jiynagi tastiyiqlansm. 2. Respublika ministrlikleri, vedomstvalari, jergilikli hakimiyat ham basqariw organlan, galaba xabar qurallari latin jaziwina tiykarlangan qaraqalpaq dipbesindegi barliq turdegi xat jazisiwlarda, baspasozde, is jiirgiziwde usi qagiydalardi engiziw boymsha tiyisli ilajlardi islep shiqsin ham amelge asirsm. -

Origin and Nature of Ancient Indian Buddhism

ORIGIN AND NATURE OF ANCIENT INDIAN BUDDHISM K.T.S. Sarao 1 INTRODUCTION Since times immemorial, religion has been a major motivating force and thus, human history cannot be understood without taking religion into consideration. However, it should never be forgotten that the study of religion as an academic discipline is one thing and its personal practice another. An objective academic study of religion carried many dangers with it. The biggest danger involved in such a study is that it challenges one’s personal beliefs more severely than any other discipline. For most people appreciation of religious diversity becomes difficult because it contradicts the religious instruction received by them. For people experiencing such a difficulty, it may be helpful to realize that it is quite possible to appreciate one’s own perspective without believing that others should also adopt it. Such an approach may be different but certainly not inferior to any other. It must never be forgotten that scholarship that values pluralism and diversity is more humane than scholarship that longs for universal agreement. An important requirement of objective academic study of religion is that one should avoid being personal and confessional. In fact, such a study must be based on neutrality and empathy. Without neutrality and empathy, it is not possible to attain the accuracy that is so basic to academic teaching and learning. The academic study of religion helps in moderating confessional zeal. Such a study does not have anything to do with proselyting, religious instruction, or spiritual direction. As a matter of fact, the academic study of religion depends upon making a distinction between the fact that knowing about and understanding a religion is one thing and believing in it another. -

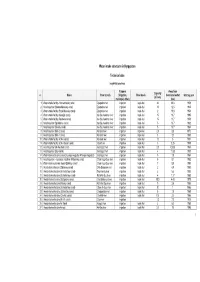

1 Water Intake Structures in Kyrgyzstan Technical Data

Water intake structures in Kyrgyzstan Technical data Issyk-Kul province Purpose Away from Capacity n Name River (canal) (irrigation, River basin river/canal outlet Start-up year (m3/sec) municipal, other) (km) 1 Water-intake facility - Komsomolsky canal Djergalan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 42 20,8 1958 2 Head regulator (Sredne-Maevsky canal) Djergalan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 10 12,5 1945 3 Water-intake facility (Staro-Maevsky canal) Djergalan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 2 19,8 1954 4 Water-intake facility (Karadjal canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 15 18,7 1995 5 Water-intake facility (Ppobeda canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 15 13,7 1959 6 Head regulator (Spiridonov canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 5 13,7 1932 7 Head regulator (Sovety canal) Ak-Suu-Arashan river irrigation Issyk-Kul 5 13,7 1934 8 Head regulator (M.K-2 canal) Karakol river irrigation Issyk-Kul 2,5 8,8 1970 9 Head regulator (M.K-1 canal) Karakol river irrigation Issyk-Kul 3 3,3 1965 10 Water-intake facility (M.K-6 canal) Karakol river irrigation Issyk-Kul 12 5 1957 11 Water-intake facility (M.K-4 feeder canal) Irdyk river irrigation Issyk-Kul 3 0,25 1959 12 Head regulator (Ak-Kochkor canal) Jeti-Oguz river irrigation Issyk-Kul 2,5 0,336 1954 13 Head regulator (Say canal) Jeti-Oguz river irrigation Issyk-Kul 4 11,35 1930 14 Water intake structure (canals: Levaya magistral, Pravaya magistral) Jeti-Oguz river irrigation Issyk-Kul 5 1,8 1964 15 Head regulator – automatic machine (Polyansky canal) Chon Kyzyl-Suu river irrigation -

Climate-Proofing Cooperation in the Chu and Talas River Basins

Climate-proofing cooperation in the Chu and Talas river basins Support for integrating the climate dimension into the management of the Chu and Talas River Basins as part of the Enhancing Climate Resilience and Adaptive Capacity in the Transboundary Chu-Talas Basin project, funded by the Finnish Ministry for Foreign Affairs under the FinWaterWei II Initiative Geneva 2018 The Chu and Talas river basins, shared by Kazakhstan and By way of an integrated consultative process, the Finnish the Kyrgyz Republic in Central Asia, are among the few project enabled a climate-change perspective in the design basins in Central Asia with a river basin organization, the and activities of the GEF project as a cross-cutting issue. Chu-Talas Water Commission. This Commission began to The review of climate impacts was elaborated as a thematic address emerging challenges such as climate change and, annex to the GEF Transboundary Diagnostic Analysis, to this end, in 2016 created the dedicated Working Group on which also included suggestions for adaptation measures, Adaptation to Climate Change and Long-term Programmes. many of which found their way into the Strategic Action Transboundary cooperation has been supported by the Programme resulting from the project. It has also provided United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) the Commission and other stakeholders with cutting-edge and other partners since the early 2000s. The basins knowledge about climate scenarios, water and health in the are also part of the Global Network of Basins Working context of climate change, adaptation and its financing, as on Climate Change under the UNECE Convention on the well as modern tools for managing river basins and water Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and scarcity at the national, transboundary and global levels. -

Hydrochemical Composition and Potentially Toxic Elements in the Kyrgyzstan Portion of the Transboundary Chu-Talas River Basin, C

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Hydrochemical composition and potentially toxic elements in the Kyrgyzstan portion of the transboundary Chu‑Talas river basin, Central Asia Long Ma1,2,3*, Yaoming Li1,2,3, Jilili Abuduwaili1,2,3, Salamat Abdyzhapar uulu2,4 & Wen Liu1,2,3 Water chemistry and the assessment of health risks of potentially toxic elements have important research signifcance for water resource utilization and human health. However, not enough attention has been paid to the study of surface water environments in many parts of Central Asia. Sixty water samples were collected from the transboundary river basin of Chu-Talas during periods of high and low river fow, and the hydrochemical composition, including major ions and potentially toxic elements (Zn, Pb, Cu, Cr, and As), was used to determine the status of irrigation suitability and risks to human health. The results suggest that major ions in river water throughout the entire basin are mainly afected by water–rock interactions, resulting in the dissolution and weathering of carbonate and silicate rocks. The concentrations of major ions change to some extent with diferent hydrological periods; however, the hydrochemical type of calcium carbonate remains unchanged. Based on the water-quality assessment, river water in the basin is classifed as excellent/good for irrigation. The relationship between potentially toxic elements (Zn, Pb, Cu, Cr, and As) and major ions is basically the same between periods of high and low river fow. There are signifcant diferences between the sources of potentially toxic elements (Zn, Pb, Cu, and As) and major ions; however, Cr may share the same rock source as major ions.